Amitriptyline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌæmɪˈtrɪptɪliːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Amitrip, Elavil, Levate, other |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682388 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30–60% due to first pass metabolism |

| Protein binding | 96%<[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver[2] |

| Biological half-life | 10 to 50 hrs[2] |

| Excretion | Mostly kidney[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.038 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

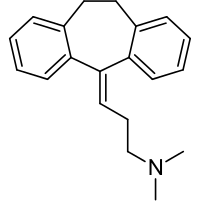

| Formula | C20H23N |

| Molar mass | 277.403 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amitriptyline, sold under the brand name Elavil among others, is a medicine used to treat a number of mental illnesses.[2] These include major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder, and less commonly attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder.[2][3] Other uses include prevention of migraines, treatment of neuropathic pain such as fibromyalgia and postherpetic neuralgia, and less commonly insomnia.[2][4] It is in the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) class and its exact mechanism of action is unclear.[2] Amitriptyline is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include a dry mouth, trouble seeing, low blood pressure on standing, sleepiness, and constipation. Serious side effects may include seizures, an increased risk of suicide in those less than 25 years of age, urinary retention, glaucoma, and a number of heart issues. It should not be taken with MAO inhibitors or the medication cisapride.[2] Amitriptyline may cause problems if taken during pregnancy.[2][5] Use during breastfeeding appears to be relatively safe.[6]

Amitriptyline was discovered in 1960[7] and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1961.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2014 is between 0.01 and 0.04 USD per dose.[10] In the United States it costs about 0.20 USD per dose.[2]

Medical uses

Amitriptyline is used for a number of medical conditions including major depressive disorder (MDD).[11][12][13] Some evidence suggests amitriptyline may be more effective than other antidepressants,[14] including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs),[15] although it is rarely used as a first-line antidepressant due to its higher toxicity in overdose and generally poorer tolerability.[12]

It is TGA-labeled for migraine prevention, also in cases of neuropathic pain disorders,[12] fibromyalgia[4] and nocturnal enuresis.[12][16] Amitriptyline is a popular off-label treatment for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),[17] although it is most frequently reserved for severe cases of abdominal pain in patients with IBS because it needs to be taken regularly to work and has a generally poor tolerability profile, although a firm evidence base supports its efficacy in this indication.[17] Amitriptyline can also be used as an anticholinergic drug in the treatment of early-stage Parkinson's disease if depression also needs to be treated.[18] Amitriptyline is the most widely researched agent for prevention of frequent tension headaches.[19]

Investigational uses

- Eating disorders:[20] The few randomized controlled trials investigating its efficacy in eating disorders have been discouraging.[21]

- Insomnia: As of 2004, amitriptyline was the most commonly prescribed off-label prescription sleep aid in the United States.[22] Owing to the development of tolerance and the potential for adverse effects such as constipation, its use in the elderly for this indication is recommended against.[12]

- Urinary incontinence. An accepted use for amitriptyline in Australia is the treatment of urinary urge incontinence.[12]

- Cyclic vomiting syndrome[23][24]

- Chronic cough[25]

- Preventive treatment for patients with recurring biliary dyskinesia (sphincter of Oddi dysfunction)[26]

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (in addition to, or sometimes in place of ADHD stimulant drugs)[27]

- Retching/dry heaving, especially after the anti-reflux procedure Nissen fundoplication[28]

Adverse effects

Common (≥1% frequency) side effects include dizziness, headache, weight gain, side effects common to anticholinergics, but more such effects than other TCAs, cognitive effects such as delirium and confusion, mood disturbances such as anxiety and agitation, cardiovascular side effects such as orthostatic hypotension, sinus tachycardia, and QT-interval prolongation,[29] sexual side effects such as loss of libido and impotence, and sleep disturbances such as drowsiness, insomnia and nightmares.[11][12][13][20][30][31]

Contraindications

The known contraindications of amitriptyline are:[31]

- Hypersensitivity to tricyclic antidepressants or to any of its excipients

- History of myocardial infarction

- History of arrhythmias, particularly heart block to any degree

- Congestive heart failure

- Coronary artery insufficiency

- Mania

- Severe liver disease

- Being under 7 years of age

- Breast feeding

- Patients who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or have taken them within the last 14 days.

Interactions

Amitriptyline is known to interact with:[30]

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors as it can potentially induce a serotonin syndrome

- CYP2D6 inhibitors and substrates such as fluoxetine due to the potential for an increase in plasma concentrations of the drug to be seen

- Guanethidine as it can reduce the antihypertensive effects of this drug

- Anticholinergic agents such as benztropine, hyoscine (scopolamine) and atropine, because the two might exacerbate each other's anticholinergic effects, including paralytic ileus and tachycardia

- Antipsychotics due to the potential for them to exacerbate the sedative, anticholinergic, epileptogenic and pyrexic (fever-promoting) effects. Also increases the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Cimetidine due to the potential for it to interfere with hepatic metabolism of amitriptyline and hence increasing steady-state concentrations of the drug

- Disulfiram due to the potential for the development of delirium

- ECT may increase the risks associated with this treatment

- Antithyroid medications may increase the risk of agranulocytosis

- Thyroid hormones have a potential for increased adverse effects such as CNS stimulation and arrhythmias.

- Analgesics, such as tramadol and pethidine due to the potential for an increase in seizure risk and serotonin syndrome.

- Medications subject to gastric inactivation (e.g. levodopa) due to the potential for amitriptyline to delay gastric emptying and reduce intestinal motility

- Medications subject to increased absorption given more time in the small intestine (e.g. anticoagulants)

- Serotoninergic agents such as the SSRIs and triptans due to the potential for serotonin syndrome.

Overdose

The symptoms and the treatment of an overdose are largely the same as for the other TCAs, including the presentation of serotonin syndrome and adverse cardiac effects. The British National Formulary notes that amitriptyline can be particularly dangerous in overdose,[13] thus it and other tricyclic antidepressants are no longer recommended as first-line therapy for depression. Alternative agents, SSRIs and SNRIs, are safer in overdose, though they are no more efficacious than TCAs. English folk singer Nick Drake died from an overdose of Tryptizol in 1974.

The possible symptoms of amitriptyline overdose include:[30]

- Drowsiness

- Hypothermia (low body temperature)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Other arrhythmic abnormalities, such as bundle branch block

- ECG evidence of impaired conduction

- Congestive heart failure

- Dilated pupils

- Convulsions (e.g. seizures, myoclonus)

- Severe hypotension (very low blood pressure)

- Stupor

- Coma

- Death

- Polyradiculoneuropathy

- Changes in the electrocardiogram, particularly QT-interval prolongation[29] and change in QRS axis or width

- Agitation

- Hyperactive reflexes

- Muscle rigidity

- Vomiting

The treatment of overdose is mostly supportive as no specific antidote for amitriptyline overdose is available.[30] Activated charcoal may reduce absorption if given within 1–2 hours of ingestion.[30] If the affected person is unconscious or has an impaired gag reflex, a nasogastric tube may be used to deliver the activated charcoal into the stomach.[30] ECG monitoring for cardiac conduction abnormalities is essential and if one is found close monitoring of cardiac function is advised.[30] Body temperature should be regulated with measures such as heating blankets if necessary.[30] Likewise, cardiac arrhythmias can be treated with propranolol and should heart failure occur, digitalis may be used.[30] Cardiac monitoring is advised for at least five days after the overdose.[30] Amitriptyline increases the CNS depressant action, but not the anticonvulsant action of barbiturates; therefore, an inhalation anaesthetic or diazepam is recommended for control of convulsions.[30] Dialysis is of no use due to the high degree of protein binding with amitriptyline.[30]

Mechanism of action

| Receptor | Ki [nM][Note 1] (amitriptyline)[32][33] | Ki [nM][Note 2] (nortriptyline)[32][33] |

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 3.13 | 16.5 |

| NET | 22.4 | 4.37 |

| DAT | 5380 | 3100 |

| 5-HT1A | 450 | 294 |

| 5-HT1B | 840 | - |

| 5-HT2A | 4.3 | 5 |

| 5-HT2C | 6.15 | 8.5 |

| 5-HT6 | 103 | 148 |

| 5-HT7 | 114 | - |

| H1 | 1.1 | 15.1 |

| H3 | 1000 | - |

| H4 | 33.6 | - |

| M1 | 12.9 | 40 |

| M2 | 11.8 | 110 |

| M3 | 25.9 | 50 |

| M4 | 7.2 | 84 |

| M5 | 19.9 | 97 |

| α1 | 24 | 55 |

| α2 | 690 | 2030 |

| D1 | 89 | - |

| D2 | 1460 | 2570 |

| D3 | 206 | - |

| D5 | 170 | - |

| σ | 300 | 2000 |

Amitriptyline acts primarily as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, with strong actions on the serotonin transporter and moderate effects on the norepinephrine transporter.[34][35] It has negligible influence on the dopamine transporter and therefore does not affect dopamine reuptake, being nearly 1,000 times weaker on it than on serotonin.[35] It is metabolised to nortriptyline—a more potent and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor—which may complement its effects on norepinephrine reuptake.[30]

Amitriptyline additionally functions as a 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, 5-HT7, α1-adrenergic, H1, H2,[36] H4,[37][38] and mACh receptor antagonist, and σ1 receptor agonist.[39][40][41][42] It has also been shown to be a relatively weak NMDA receptor negative allosteric modulator at the same binding site as phencyclidine.[43] Amitriptyline inhibits sodium channels, L-type calcium channels, and Kv1.1, Kv7.2, and Kv7.3 voltage-gated potassium channels, and therefore acts as a sodium, calcium, and potassium channel blocker as well.[44][45]

Recently, amitriptyline has been demonstrated to act as an agonist of the TrkA and TrkB receptors.[46] It promotes the heterodimerization of these proteins in the absence of NGF and has potent neurotrophic activity both in-vivo and in-vitro in mouse models.[46][47] These are the same receptors BDNF activates, an endogenous neurotrophin with powerful antidepressant effects, and as such this property may contribute significantly to its therapeutic efficacy against depression. Amitriptyline also acts as a functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase.[48]

Pharmacokinetics

Amitriptyline is a highly lipophilic molecule having a log D (octanol/water, pH 7.4) of 3.0,[49] while the log P of the free base was reported as 4.92.[50] Solubility in water is 9.71 mg/L at 24 °C.[51]

Amitriptyline is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and is extensively metabolised on first pass through the liver.[30] It is metabolised mostly by CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and CYP2C19-mediated N-demethylation into nortriptyline,[30] which is another tricyclic antidepressant in its own right.[52] It is 96% bound to plasma proteins, nortriptyline is 93-95% bound to plasma proteins.[30][53] It is mostly excreted in the urine (around 30–50%) as metabolites either free or as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates.[30] Small amounts are also excreted in feces.[20]

Pharmacogenetics

Since amitriptyline is primarily metabolized by CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, genetic variations within the genes coding for these enzymes can affect its metabolism, leading to changes in the concentrations of the drug in the body.[54] Increased concentrations of amitriptyline may increase the risk for side effects, including anticholinergic and nervous system adverse effects, while decreased concentrations may reduce the drug's efficacy.[55][56][57]

Individuals can be categorized into different types of CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 metabolizers depending on which genetic variations they carry. These metabolizer types include poor, intermediate, extensive, and ultrarapid metabolizers. Most individuals (about 77-92%) are extensive metabolizers,[57] and have "normal" metabolism of amitriptyline. Poor and intermediate metabolizers have reduced metabolism of the drug as compared to extensive metabolizers; patients with these metabolizer types may have an increased probability of experiencing side effects. Ultrarapid metabolizers use amitriptyline much faster than extensive metabolizers; patients with this metabolizer type may have a greater chance of experiencing pharmacological failure.[55][56][57]

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium recommends avoiding amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 ultrarapid or poor metabolizers, due to the risk for a lack of efficacy and side effects, respectively. The consortium also recommends considering an alternative drug not metabolized by CYP2C19 in patients who are CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizers. A reduction in starting dose is recommended for patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers and CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. If use of amitriptyline is warranted, therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended to guide dose adjustments.[57] The Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group also recommends selecting an alternative drug or monitoring plasma concentrations of amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 poor or ultrarapid metabolizers, and selecting an alternative drug or reducing initial dose in patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers.[58]

Brand names

Brand names include (just including those used in English-speaking countries with † to indicate discontinued brands):[52][59]

- Amirol (NZ)

- Amit (IN)

- Amitone (IN)

- Amitor (IN)

- Amitrip (AU,† IN, NZ)

- Amitriptyline (UK)

- Amitriptyline Hydrochloride (UK, US)

- Amitrol† (AU)

- Amrea (IN)

- Amypres (IN)

- Crypton (IN)

- Elavil (CA, UK†, US†)

- Eliwel (IN)

- Endep (AU, HK†, ZA†, US†)

- Enovil† (US)

- Gentrip (IN)

- Kamitrin (IN)

- Laroxyl (FR)

- Latilin (IN)

- Levate (US)

- Maxitrip (IN)

- Mitryp (IN)

- Odep (IN)

- Redomex (BE)

- Qualitriptine (HK)

- Saroten (CH)

- Sarotena (IN)

- Sarotex (NO)

- Tadamit (IN)

- Trepiline (ZA)

- Triad (NP)

- Tripta (SG) (TH)

- Triptaz (IN)

- Tryptanol (ZA)

- Tryptizol (ES)

- Triptyl (FI)

- Tryptomer (IN)

Notes

References

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary: Definition of amitriptyline (British & World English)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Sep 25, 2014.

- ↑ Leucht, C; Huhn, M; Leucht, S (December 2012). "Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD009138. PMID 23235671. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009138.pub2.

- 1 2 Moore, RA; Derry, S; Aldington, D; Cole, P; Wiffen, PJ (6 July 2015). "Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD008242. PMID 26146793. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008242.pub3.

- ↑ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Amitriptyline Levels and Effects while Breastfeeding". drugs.com. Sep 8, 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery a History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 414. ISBN 9780470015520.

- ↑ Fangmann P, Assion HJ, Juckel G, González CA, López-Muñoz F (February 2008). "Half a century of antidepressant drugs: on the clinical introduction of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclics, and tetracyclics. Part II: tricyclics and tetracyclics". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (1): 1–4. PMID 18204333. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181627b60.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Amitriptyline". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- 1 2 "AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated [Dispensing Solutions, Inc.]". DailyMed. Dispensing Solutions, Inc. September 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- 1 2 3 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65th ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ↑ Barbui C, Hotopf M (February 2001). "Amitriptyline v. the rest: still the leading antidepressant after 40 years of randomised controlled trials". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 178 (2): 129–144. PMID 11157426. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.2.129.

- ↑ Anderson IM (April 2000). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". Journal of Affective Disorders. 58 (1): 19–36. PMID 10760555. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00092-0.

- ↑ Kennea, NL; Evans, JHC (June 2000). "Drug Treatment of Nocturnal Enuresis" (PDF). Paediatric and Perinatal Drug Therapy. Informa Healthcare. 4 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1185/1463009001527679.

- 1 2 Viera AJ, Hoag S, Shaughnessy J (2002). "Management of irritable bowel syndrome" (PDF). Am Fam Physician. 66 (10): 1867–74. PMID 12469960.

- ↑ Parkinson's disease. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. August 2007. Retrieved on 2013-12-22.

- ↑ PJ Millea; JJ Brodie (2002-09-01). "Tension-Type Headache". Am Fam Physician. 66 (5): 797–805.

- 1 2 3 "Levate (amitriptyline), dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 189–207. PMID 21414249. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381.

- ↑ Mendelson WB, Roth T, Cassella J, Roehrs T, Walsh JK, Woods JH, Buysse DJ, Meyer RE (February 2004). "The treatment of chronic insomnia: drug indications, chronic use and abuse liability. Summary of a 2001 New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting symposium". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (1): 7–17. PMID 15062207. doi:10.1016/s1087-0792(03)00042-x.

- ↑ Sim Y-J, Kim J-M, Kwon S, Choe B-H (2009). "Clinical experience with amitriptyline for management of children with cyclic vomiting syndrome". Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 52 (5): 538–43. doi:10.3345/kjp.2009.52.5.538.

- ↑ Boles RG, Lovett-Barr MR, Preston A, Li BU, Adams K (2010). "Treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome with co-enzyme Q10 and amitriptyline, a retrospective study". BMC Neurol. 10: 10. PMC 2825193

. PMID 20109231. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-10-10.

. PMID 20109231. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-10-10. - ↑ Chung, KF (2008). "Currently available cough suppressants for chronic cough.". Lung. 186 Suppl 1: S82–7. PMID 17909897. doi:10.1007/s00408-007-9030-1.

- ↑ Wald, Arnold (2006). "Functional biliary type pain syndrome". In Pasricha, Pankaj Jay; Willis, William D.; Gebhart, G. F. Chronic Abdominal and Visceral Pain. London: Informa Healthcare. pp. 453–62. ISBN 978-0-8493-2897-8.

- ↑ http://www.drugs.com/monograph/amitriptyline-hydrochloride.html

- ↑ http://gi.org/guideline/management-of-gastroparesis

- 1 2 Wesley R. Zemrak, Pharm.D.; George A. Kenna, Ph.D., B.S.Pharm (2008). "Association of Antipsychotic and Antidepressant Drugs With Q-T interval Prolongation". WebMD LLC. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Endep Amitriptyline hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 "Amitriptyline Tablets BP 50mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Actavis UK Ltd. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ↑ "Potency of antidepressants to block noradrenaline reuptake". CNS Forum. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- 1 2 Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. PMID 9537821. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01393-9.

- ↑ Albert Ellis; Gwynn Pennant Ellis (1 January 1987). Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-444-80876-9. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Nguyen T, Shapiro DA, George SR, Setola V, Lee DK, Cheng R, Rauser L, Lee SP, Lynch KR, Roth BL, O'Dowd BF (March 2001). "Discovery of a novel member of the histamine receptor family". Molecular Pharmacology. 59 (3): 427–33. PMID 11179435.

- ↑ D. Sriram; P. Yogeeswari (1 September 2010). Medicinal Chemistry. Pearson Education India. p. 299. ISBN 978-81-317-3144-4. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (December 1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- ↑ Alan F. Schatzberg; Charles B. (2006). Essentials of clinical psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-58562-243-6.

- ↑ Rauser L, Savage JE, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (October 2001). "Inverse agonist actions of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs at the human 5-hydroxytryptamine(2C) receptor". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299 (1): 83–9. PMID 11561066.

- ↑ Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, Nuwayhid SJ (October 2007). "A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder". Exp. Neurol. 207 (2): 248–57. PMID 17689532. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.013.

- ↑ Sills MA, Loo PS (July 1989). "Tricyclic antidepressants and dextromethorphan bind with higher affinity to the phencyclidine receptor in the absence of magnesium and L-glutamate". Mol. Pharmacol. 36 (1): 160–5. PMID 2568580.

- ↑ Pancrazio JJ, Kamatchi GL, Roscoe AK, Lynch C (January 1998). "Inhibition of neuronal Na+ channels by antidepressant drugs". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 284 (1): 208–14. PMID 9435180.

- ↑ Punke MA, Friederich P (May 2007). "Amitriptyline is a potent blocker of human Kv1.1 and Kv7.2/7.3 channels". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 104 (5): 1256–1264. PMID 17456683. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000260310.63117.a2.

- 1 2 Jang SW, Liu X, Chan CB, Weinshenker D, Hall RA, Xiao G, Ye K (June 2009). "Amitriptyline is a TrkA and TrkB receptor agonist that promotes TrkA/TrkB heterodimerization and has potent neurotrophic activity". Chem. Biol. 16 (6): 644–56. PMC 2844702

. PMID 19549602. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.010.

. PMID 19549602. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.010. - ↑ "Pharmaceutical Information - AMITRIPTYLINE". RxMed. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, Mühle C, Terfloth L, Groemer TW, Spitzer GM, Liedl KR, Gulbins E, Tripal P (2011). Riezman H, ed. "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. PMC 3166082

. PMID 21909365. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852.

. PMID 21909365. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. - ↑ The Pharmaceutical Codex. 1994. Principles and practice of pharmaceutics, 12th edn. Pharmaceutical press

- ↑ Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995. Exploring QSAR.Hydrophobic, electronic and steric constants. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

- ↑ Yalkowsky SH, Dannenfelser RM; The AQUASOL dATAbASE of Aqueous Solubility. Ver 5. Tucson, AZ: Univ AZ, College of Pharmacy (1992)

- 1 2 Amitriptyline. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ "Pamelor, Aventyl (nortriptyline) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Rudorfer MV, Potter WZ (1999). "Metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (3): 373–409. PMID 10319193.

- 1 2 Stingl JC, Brockmoller J, Viviani R (2013). "Genetic variability of drug-metabolizing enzymes: the dual impact on psychiatric therapy and regulation of brain function". Mol Psychiatry. 18 (3): 273–87. PMID 22565785. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.42.

- 1 2 Kirchheiner J, Seeringer A (2007). "Clinical implications of pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 drug metabolizing enzymes". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1770 (3): 489–94. PMID 17113714. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.019.

- 1 2 3 4 Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Kharasch ED, Ellingrod VL, Skaar TC, Muller DJ, Gaedigk A, Stingl JC (2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Tricyclic Antidepressants". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 93 (5): 402–8. PMC 3689226

. PMID 23486447. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2.

. PMID 23486447. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2. - ↑ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A, Grandia L, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Mulder H, Rongen GA, van Schaik RH, Schalekamp T, Touw DJ, van der Weide J, Wilffert B, Deneer VH, Guchelaar HJ (2011). "Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte--an update of guidelines". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 89 (5): 662–73. PMID 21412232. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34.

- ↑ "Amitriptyline". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

Further reading

- PubChem Substance Summary: Amitriptyline National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- TREPILINE-10 TABLETS; TREPILINE-25 TABLETS South African Electronic Package Inserts. 12 May 1978. Revised February 2004.

- SAROTEN RETARD 25 mg Capsules; SAROTEN RETARD 50 mg Capsules South African Electronic Package Inserts. December 1987. Updated May 2000.

- AMITRIP Amitriptyline hydrochloride 10 mg, 25 mg and 50 mg Capsules Medsafe NZ Physician Data Sheet. November 2004.

- Endep Consumer Medicine Information, Australia. December 2005.

- MedlinePlus Drug Information: Amitriptyline. US National Institutes of Health. January 2008.