Emanuel Schikaneder

Emanuel Schikaneder (1 September 1751 – 21 September 1812), born Johann Joseph Schickeneder, was a German impresario, dramatist, actor, singer and composer. He wrote the libretto of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera The Magic Flute and was the builder of the Theater an der Wien. Branscombe called him "one of the most talented theatre men of his era".

Early years

Schikaneder was born in Straubing in Bavaria to Joseph Schickeneder and Juliana Schiessl. Both of his parents worked as domestic servants and were extremely poor.[2] They had a total of four children: Urban (born 1746), Johann Joseph (died at age two), Emanuel (born 1751 and also originally named Johann Joseph), and Maria (born 1753).[2] Schikaneder's father died shortly after Maria's birth,[2] at which time his mother returned to Regensburg, making a living selling religious articles from a wooden shed adjacent to the local cathedral.[2]

Schikaneder received his education at a Jesuit school in Regensburg as well as training in the local cathedral as a singer.[3] As a young adult he began to pursue his career in the theater, appearing with Andreas Schopf's theatrical troupe around 1773 and performing opera, farce, and Singspiel.[2] Schikaneder danced at a court ballet in Innsbruck in 1774, and the following year his Singspiel Die Lyranten was debuted there. This was a great success, and was performed frequently in the following years.[2] Schikaneder was the librettist, composer, and principal singer,[3] a versatility he would continue to exhibit throughout his career.[4]

Schikaneder married on 9 February 1777. His wife, called Eleonore, was born Maria Magdalena Arth in 1751 and was the leading actress in the Schopf company.[5] Schikaneder was frequently unfaithful to her; the 1779 baptismal records for Augsburg (where the company was performing) record two children born to him out of wedlock—each to different mothers.[6] Eleonore played an important role in Schikaneder's career, particularly in inviting him in 1788 to join her at the Theater auf der Wieden (see below). She died in 1821.[5]

In 1777 Schikaneder performed the role of Hamlet in Munich to general acclaim. In the same year, he and Eleonore joined the theatrical troupe of Joseph Moser in Nuremberg[6] Following the death of his wife, Moser handed over the management of his troupe to Schikaneder in 1778.[6]

Befriending the Mozarts

In the fall of 1780, the Schikaneder troupe made an extended stay in Salzburg, and at that time Schikaneder became a family friend of the Mozarts. The Mozart family at the time consisted of father Leopold, Nannerl, and Wolfgang. The Mozarts "rarely missed his shows" (Heartz),[3] and invited Schikaneder to Sunday sessions of Bölzlschiessen (dart shooting), their favorite family sport.

As Mozart was about to depart Salzburg for the premiere in Munich of his opera Idomeneo, he promised before leaving to write "Wie grausam ist, o Liebe...Die neugeborne Ros' entzückt", a recitative and aria for Schikaneder. The composition was intended for Schikaneder's production of Die zwey schlaflosen Nächte by August Werthes.[7]

The first stay in Vienna

From November 1784 to February 1785,[8] Schikaneder collaborated with theater director Hubert Kumpf for a series of performances at the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna. He had been invited to do so by the Emperor Joseph II, who had seen him perform the previous year in Pressburg.[9] The Vienna run was admired by critics and attracted large audiences, often including the Emperor and his court.[10] Schikaneder and Kumpf opened their season with a revival of Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Joseph Haydn's La fedeltà premiata was also performed by the troupe.[11]

Works of spoken drama were of interest for their political content. The Austrian Empire at the time was governed (like most of Europe) by the system of hereditary aristocracy, which was falling under increasing criticism as the values of the Enlightenment spread. Schikaneder put on a successful comedy entitled Der Fremde which included a character named Baron Seltenreich ("seldom-rich") who was "a caricature of a scheming windbag of the Viennese aristocracy".[12] Schikaneder and his colleague then stepped over the line, initiating a production of Beaumarchais' then-scandalous send-up of the aristocracy, The Marriage of Figaro. This production was canceled by the Emperor at the last minute.[12]

In spite of the content and cancellation of the production, Joseph II brought Schikaneder entered Imperial service from April 1785 through February 1786.[13] During his service, he performed in the Austrian Nationaltheater[9] at Burgtheater. During his debut he sang the role of Schwindel in Gluck's Singspiel Die Pilgrime von Mekka.[5]

In 1785, Schikaneder's wife Eleonore left him as a result of his infidelities. She moved in with Schikaneder's former colleague, Johann Friedel, and formed a traveling theater troupe with him.[14] Schikaneder's brother Urban was also a part of this group.[6]

Schikaneder was discontented at the Nationaltheater; in his previous career he had normally played leading roles such as (in translated Shakespeare), Hamlet, Macbeth, Iago, and Othello.[15] His main successes at the Nationaltheater were as a singer.[16] Seeking new options, Schikaneder proposed to the Emperor that he be allowed to build a new theater in the suburbs, a request that quickly received the Emperor's official approval.[16] However, the plan remained unfulfilled at that time.

Eventually, Schikaneder formed a new troupe and left Vienna to tour the provinces. They played in Salzburg (May 1786; Schikaneder renewed his friendship with Leopold Mozart), then Augsburg (June 1786). During the years 1787 to 1789, the troupe performed in Schikaneder's home town of Regensburg, where they functioned as the resident company in the theater of the reigning Prince, Carl Anselm von Thurn und Taxis.[5]

Years at the Theater auf der Wieden

During Easter 1788, the troupe run by Johann Friedel and Eleonore Schikaneder had settled as the resident troupe at the Theater auf der Wieden, located in a suburb of Vienna.[5] Friedel died March 31, 1789, leaving his entire estate to Eleonore, and the theater was closed. Following this, Eleonore offered reconciliation to Schikaneder, who moved to Vienna in May to start a new company in the same theater in partnership with her.[17] The new company was financed by Joseph von Bauernfeld, a Masonic brother of Mozart [18] With plans of an emphasis on opera, Schikaneder brought two singers with him from his old troupe, tenor Benedikt Schack and bass Franz Xaver Gerl. From his wife's company he retained soprano Josepha Hofer, actor Johann Joseph Nouseul, and Karl Ludwig Giesecke as librettist. New additions to the troupe included Anna Gottlieb and Jakob Haibel.[19]

The new company was successful, and Die Entführung aus dem Serail again became part of the repertory. Several aspects of the company's work emerged that later came to be immortalized in The Magic Flute. A series of musical comedies starting with Der Dumme Gärtner aus dem Gebirge, oder Die zween Antons ("The Foolish Gardener from the Mountains, or The Two Antons"), premiered in July 1789.[19] The comedy provided a vehicle for Schikaneder's comic stage persona. Another line of performances by the company involved fairy tale operas, starting with the 1789 premiere of Oberon, with music by Paul Wranitzky and a libretto that was a readaptation of Sophie Seyler's original libretto. This was followed by Der Stein der Weisen oder Die Zauberinsel in September 1790,[20] a collaborative opera marked by the musical collaboration of Gerl, Schack, Schikaneder and Mozart.

The theater emphasized stage effects and spectacle including "flying machines, trapdoors, thunder, elaborate lighting and other visual effects including fires and waterfalls."[21] Evidence also suggests that the standard of musicianship was (contrary to earlier assertions), quite high. David Buch writes:

A ... myth about this theater has also persisted in modern literature, namely, that the music was of an inferior quality and that the performances were rather crude. While there is one derisive review of a performance at the Theater auf der Wieden by a north German commentator in 1793, most contemporary reviews were positive, noting a high standard of musical performance. In his unpublished autobiography, Ignaz von Seyfried recalled performances of operas in the early 1790s by Mozart, Süßmayr, Hoffmeister etc., writing that they were performed with rare skill (ungemein artig). Seyfried describes Kapellmeister Henneberg conducting the orchestra from the “pianoforte ... like a General commanding an army of musicians!”[22]

The Magic Flute

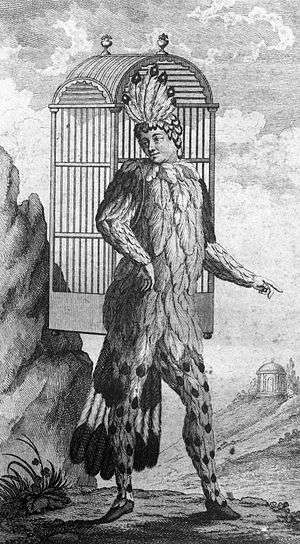

The series of fairy-tale operas at the Theater auf der Wieden culminated in the September 1791 premiere of The Magic Flute, with music by Mozart and libretto by Schikaneder.[23] The opera incorporated a loose mixture of Masonic elements and traditional fairy-tale themes (see Libretto of The Magic Flute). Schikaneder took the role of Papageno—a character reflecting the Hanswurst tradition, and thus suited to his skills—at the premiere.

According to the dramatist Ignaz Franz Castelli, Schikaneder also may have given advice to Mozart concerning the musical setting of his libretto:

The late bass singer Sebastian Mayer told me that Mozart had originally written the duet where Papageno and Papagena first see each other quite differently from the way in which we now hear it. Both originally cried out "Papageno!", "Papagena!" a few times in amazement. But when Schikaneder heard this, he called down into the orchestra, "Hey, Mozart! That's no good, the music must express greater astonishment. They must both stare dumbly at each other, then Papageno must begin to stammer: 'Pa-papapa-pa-pa'; Papagena must repeat that until both of them finally get the whole name out. Mozart followed the advice, and in this form the duet always had to be repeated."

Castelli adds that the March of the Priests which opens the second act was also a suggestion of Schikaneder's, added to the opera at the last minute by Mozart. These stories are not accepted as necessarily true by all musicologists.[24]

The Magic Flute was a great success at its premiere, frequently selling out and receiving over a hundred performances at the Theater auf der Wieden during its first few months of performance. Schikaneder continued to produce the opera at intervals for the rest of his career in Vienna.

Mozart died only a few weeks after the premiere, on 5 December 1791. Schikaneder was distraught at the news and felt the loss sharply. He evidently put on a benefit performance of The Magic Flute for Mozart's widow Constanze, who at the time faced a difficult financial situation.[25] When his troupe mounted a concert performance of Mozart's La clemenza di Tito in 1798, he wrote in the program:

Mozart's work is beyond all praise. One feels only too keenly, on hearing this or any other of his music, what the Art has lost in him.[26]

Remaining years

Schikaneder's career continued in the same theater during the years that followed The Magic Flute. He continued to write works in which he played the main role and which achieved popular success. These included collaborations with other composers of the time: Der Spiegel von Arkadien with Mozart's assistant Franz Xaver Süssmayr, Der Tyroler Wastel with Mozart's posthumous brother-in-law Jakob Haibel, and a Magic Flute sequel called Das Labyrinth, with Peter von Winter.[27] A big box office draw during this time was a rhymed-verse comedy, Der travestierte Aeneas (The Travesty of Aeneas), a contribution of Giesecke.[28]

During this period, Schikaneder would several times a year devote the theater to an Academie, or in modern terms, a classical music concert. Symphonies of Mozart and Haydn were performed, and a young Beethoven appeared as a piano soloist.[29]

Schikaneder maintained in the repertory six Mozart operas: Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Le nozze di Figaro, Der Schauspieldirektor, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, La clemenza di Tito, and The Magic Flute. The Italian operas were performed in German translation. As noted above, Schikaneder also produced La clemenza di Tito as a concert work.[29]

Although many of the works performed were popular successes, the expenses of Schikaneder's elaborate productions were high, and the company gradually fell into debt. In 1798, Schikaneder's landlord learned that the debt had risen to 130,000 florins and canceled Schikaneder's lease. Schikaneder persuaded Bartholomäus Zitterbarth, a wealthy merchant, to become his partner and take on the debt. As a result, the company was saved.[30]

The Theater an der Wien

Schikaneder and new partner Zitterbarth planned together to construct a grand new theater for the company. Zitterbarth purchased the land for the new theater on the other side of the Wien River, in another suburb only a few hundred meters away from the Theater auf der Wieden.[30] Schikaneder still had in his possession a document from the late Emperor Joseph II permitting him to construct a new theater. In 1800, he had an audience with the now-reigning Franz, which resulted in a renewal of the license—over the protests of Peter von Braun, who directed the Burgtheater.[30] In retaliation, Braun mounted a new production of The Magic Flute at the Burgtheater, which did not mention Schikaneder as the author.[31]

Construction of the new theater, which was named the Theater an der Wien, began in April 1800. It opened 13 June 1801 with a performance of the opera Alexander, to Schikaneder's own libretto with music by Franz Teyber.[32] According to the New Grove, the Theater an der Wien was "the most lavishly equipped and one of the largest theatres of its age". There, Schikaneder continued his tradition of expensive and financially risky theatrical spectacle.[33]

Schikaneder and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven had moved to Vienna in 1792 and gradually established a strong reputation as a composer and pianist. He performed in an Academie at the Theater auf der Wieden during its last years. In the spring of 1803, the first Academie at the new Theater an der Wien was devoted entirely to Beethoven's works: the first and second symphonies, the third piano concerto (with Beethoven as soloist), and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives.[34]

Schikaneder wanted Beethoven to compose an opera for him. After offering Beethoven an apartment to live in inside the theater building, he also offered his libretto, Vestas Feuer. Beethoven, however, found Vestas Feuer unsuited to his needs. He did, however, set the opening scene, part of which ultimately became the duet "O namenlose Freude" from his 1804 opera Fidelio. Beethoven continued to live in the Theater an der Wien for a while as he switched his efforts to Fidelio.[34]

Decline and demise

Fidelio premiered in the Theater an der Wien, but not under Schikaneder's direction. By 1804, Schikaneder's career had taken a downward turn; his productions could not bring in enough customers to cover their cost. He sold the Theater an der Wien to a consortium of nobles and left Vienna for the provinces,[33] working in Brno and Steyr. Following economic problems caused by war and an 1811 currency devaluation, Schikaneder lost most of his fortune. During a journey to Budapest in 1812 to take a new post, he was stricken with insanity. He died impoverished in Vienna on September 21, 1812 at age 61.

Kin

Two of Schikaneder's relatives were also his professional associates:

- Urban Schikaneder (1746–1818), a bass, was Emanuel's older brother. He was born in Regensburg on 2 November 1746, and worked for a number of years in his brother's troupe, both as a singer and in helping to administer the group. At the premiere of The Magic Flute, he sang the role of the First Priest.[35]

- Anna Schikaneder, (1767–1862) also called "Nanny" or "Nanette", was brother Urban's daughter. At age 24 she sang the role of the First Boy in The Magic Flute.[35]

Schikaneder's illegitimate son Franz Schikaneder (1802–1877) was a blacksmith in the service of emperor Ferdinand I of Austria.[36]

Works

Works by Schikaneder[37] include 56 libretti and 45 spoken-language plays, among them:

Libretti

- Die Lyranten oder das lustige Elend (The Minstrels, or Merry Misery). Operetta, music by Schikaneder, Innsbruck, ca. 1775.

- Das Urianische Schloss (The Urian Castle) Singspiel, music by Schikander, Salzburg, 1786.

- Der dumme Gärtner aus dem Gebirge oder die zween Anton (The Silly Gardener from the Hills, or The Two Antons). Comic opera, music by Benedikt Schack and Franz Xaver Gerl. Vienna, 1789.

- Five sequels to the latter work, including

- Was macht der Anton im Winter? (What does Anton do in Winter?) Music by Benedikt Schack and Franz Xaver Gerl. Vienna, 1790.

- Anton bei Hofe, oder Das Namensfest (Anton at Court, or The Name-Day) (Vienna, 4 June 1791). Mozart heard the work on 6 June.[38]

- Five sequels to the latter work, including

- Der Stein der Weisen (The Philosopher's Stone or the Magic Isle). Heroic-comic opera, Music by Benedikt Schack, Johann Baptist Henneberg, Franz Xaver Gerl, Emanuel Schikaneder, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Vienna 11 September 1790.[33][20]

- Der Fall ist noch weit seltner (opera libretto, Vienna 1790; music by Benedikt Schack[39])

- Die Zauberflöte (opera libretto, Vienna 1791)[33]

- Der Spiegel von Arkadien (The Mirror of Arcadia). Grand heroic-comic opera, music by Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Vienna, 1794.

- Babylons Pyramiden (opera libretto)[33]

- Das Labyrinth oder Der Kampf mit den Elementen. Der Zauberflöte zweyter Theil, Heroic-comic opera, Music by Peter von Winter Vienna, 1798.

- Der Tiroler Wastel (opera libretto)[33]

- Vestas Feuer (opera libretto, Vienna 1803)

Plays

Notes

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 407)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dent (1956, 16)

- 1 2 3 Heartz (2009, 270)

- ↑ Concerning Schikaneder as composer, Branscombe (2006) observes that a recently discovered score of the 1790 collaborative opera Der Stein der Weisen oder Die Zauberinsel lists Schikaneder as composer of some of the numbers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clive (1993, 135)

- 1 2 3 4 Dent (1956, 17)

- ↑ Edge (1996, 182–85)

- ↑ Deutsch 1965, 225

- 1 2 Heartz (2009, 271)

- ↑ Deutsch and Eisen (1991, 33–34)

- ↑ Deutsch and Eisen (1991, 34)

- 1 2 Honolka (1990, 58)

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 235)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 59). Clive (1993, 135) suggests that Eleonore and Friedel may have simply taken over Schikaneder's company.

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 40)

- 1 2 Honolka (1990, 59)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 71)

- ↑ (Deutsch 1965, 360)

- 1 2 Clive (1993, 136)

- 1 2 Deutsch (1965, 370)

- ↑ Waldorf (2006, 541)

- ↑ David J. Buch, "The House Composers of the Theater auf der Wieden in the Time of Mozart (1789-91)," posted on line at

- ↑ Mainstream scholarship attributes the libretto to Schikaneder; for an alternative considered marginal see Karl Ludwig Giesecke.

- ↑ According to records, Sebastian Meyer was not employed by the Schikaneder troupe until 1793, two years after the premiere of The Magic Flute. However, he was the second husband of Josepha Hofer who, as the first Queen of the Night, was certainly present. For skeptical comment on these tales, see Branscombe (1965).

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 425)

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 487)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, ch. 6)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 183)

- 1 2 Honolka (1990, 153)

- 1 2 3 Honolka (1990, 182)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 183–185)

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 187)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Branscombe (2006)

- 1 2 Honolka (1990, 200)

- 1 2 Grove, "Schikaneder"

- ↑ Lorenz, 2008, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Honolka (1990, 222–226)

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 396)

- ↑ Deutsch (1965, 367)

References

The most extensive source on Schikaneder in English is Honolka (1990), listed below.

- Branscombe, Peter (1965) "Die Zauberflöte: Some Textual and Interpretative Problems," Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 45–63.

- Branscombe, Peter (1991) W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte (Cambridge Opera Handbooks), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521319164

- Branscombe, Peter (2006) "Schikaneder, Emanuel". In Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe, eds., The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buch, David (1997) "Mozart and the Theater auf der Wieden: New Attributions and Perspectives," Cambridge Opera Journal, pp. 195–232.

- Clive, Peter (1993) Mozart and his Circle: A Biographical Dictionary. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dent, Edward J. (1956) "Emanuel Schikaneder", Music and Letters 37:14–21.

- Edge, Dexter (1996) "A newly Discovered Autograph Source for Mozart's Aria K.365a (Anh.11a)" Mozart-Jahrbuch 1996 177–193.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1965) Mozart: A Documentary Biography; English translations by Eric Blom, Peter Branscombe, and Jeremy Noble, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. This book contains many mentions of Schikaneder from first-hand sources. The stories from Ignaz Franz Castelli were taken by Deutsch from Castelli's 1861 memoirs.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich and Cliff Eisen (1991) New Mozart documents: a supplement to O.E. Deutsch's documentary biography. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1955-1.

- Heartz, Daniel (2009) Haydn, Mozart, and early Beethoven, 1781–1802. New York: Norton.

- Honolka, Kurt (1990) Papageno: Emanuel Schikaneder, man of the theater in Mozart's time. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-931340-21-5.

- Lorenz, Michael: "Neue Forschungsergebnisse zum Theater auf der Wieden und Emanuel Schikaneder", Wiener Geschichtsblätter 4/2008, (Vienna: Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Wien, 2008), pp. 15–36. (in German)

- Waldoff, Jessica (2006) "Die Zauberflöte". In Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe, eds., The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Der Zauberfloete zweyter Theil unter dem Titel: Das Labyrinth oder der Kampf mit den Elementen. (Libretto) ed. by Manuela Jahrmärker and Till Gerrit Waidelich, Tutzing 1992, ISBN 3-7952-0694-4

- Schikaneders heroisch-komische Oper Der Stein der Weisen – Modell für Mozarts Zauberflöte. Kritische Ausgabe des Textbuches, ed. by D. Buch and Manuela Jahrmärker, vol. 5 of Hainholz Musikwissenschaft, Göttingen 2002. 119 pages. (in German)

Further reading

- Waidelich, Till Gerrit (2012) "Papagenos Selbstvermarktung in Peter von Winters Labyrinth (Der Zauberflöte zweyter Theil) sowie unbekannte Dokumente zu dessen Entstehung, Überlieferung und Rezeption in Wien und Berlin 1803", in: Acta Mozartiana, 59 (2012), pp. 139–177.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emanuel Schikaneder. |

- Schikaneder's libretto for The Magic Flute

- Michael Lorenz: Neue Forschungsergebnisse zum Theater auf der Wieden und Emanuel Schikaneder, Wiener Geschichtsblätter 4/2008, (Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Wien, Wien 2008), pp. 15–36. (in German)