Islamic history of Yemen

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Yemen |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

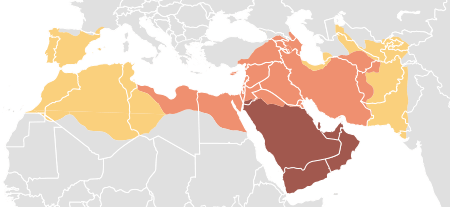

Islam came to Yemen around 630 during Muhammad's lifetime and the rule of the Persian governor Badhan. Thereafter, Yemen was ruled as part of Arab-Islamic caliphates, and became a province in the Islamic empire.

Regimes affiliated to the Egyptian Fatimid caliphs occupied much of northern and southern Yemen throughout the 11th century, including the Sulayhids and Zurayids, but the country was rarely unified for any long period of time. Local control in the Middle Ages was exerted by a succession of families which included the Ziyadids (818-1018), the Najahids (1022-1158), the Egyptian Ayyubids (1174-1229) and the Turkoman Rasulids (1229-1454). The most long-lived, and for the future most important polity, was founded in 897 by Yayha bin Husayn bin Qasim ar-Rassi. They were the Zaydis of Sa'dah in the highlands of North Yemen, headed by imams of various Sayyid lineages. As ruling Imams of Yemen, they established a Shia theocratic political structure that survived with some intervals until 1962.

After the introduction of coffee in the 16th century the town of al-Mukha (Mocha), on the Red Sea coast, became the most important coffee port in the world. For a period after 1517, and again in the 19th century, Yemen was a nominal part of the Ottoman Empire, although on both occasions the Zaydi Imams contested the power of the Turks and eventually expelled them.

Age of Muhammad

In the time of Muhammad, the Yemeni lands included the large tribal confederations Himyar, Madh'hij, Kindah, Hashid, Bakil, and Azd. An aristocratic group of Persian origins, Abna, dominated Sana'a. After the dissolution of Persian rule in South Arabia, the Abna turned to the emerging Islamic state in order to find support against local Arab rebels.[1] Islam was introduced by functionaries of Muhammad, but the extent of conversion is not known. The land remained much like it had been in pre-Islamic times, and the new religion became another factor in the internal conflicts that afflicted Yemeni society since old. A certain al-Aswad al-Ansi proclaimed himself prophet in 632 and found some support among the Yemenis. He was, however, killed by the Abna and defecting members of his own faction in the same year.[2]

The four rightly-guided Caliphs (632-661)

The leader of the Abna, Fayruz al-Daylami, supported the Muslim side in the so-called Ridda wars that afflicted the Arabian Peninsula in 632-633 following the death of Muhammad, confirming the inclusion of Yemen in the Caliphate. The so-called right-guided caliphs (Rashidun) sent governors to Yemen to rule over San'a, al-Janad, and Hadramawt, but they were never able control the entire country. The caliphs put quite some attention to the affairs of Yemen. Judges and Qur'an instructors were also appointed. The Christian tribes of Najran were evicted; however, the Jewish population was allowed to remain against the payment of the jizya. During the first civil war in the Caliphate (656-661), the Caliph Ali as well as his opponent Muawiyah I sent troops to Yemen.[3]

From the start, the Yemeni were in the vanguard of the expanding Islamic armies and were entrusted a number of important tasks. During their participation in the armies of Islam, the Yemeni transferred much of their knowledge and know-how. They clearly and evidently participated in founding towns and building fortresses, as well as the construction of castles and other skills. The Yemeni involvement in the course of events did not cease during the Caliphate. In this period Yemen was divided into three regions whose centers were San'a, al-Janad by Ta'izz, and Hadramawt.

Umayyad Caliphs (661-750)

The troops of Muawiyah, founder of the Umayyad Dynasty, conquered San'a and Najran in 660. The Umayyads shifted their base outside the Arabian Peninsula, but continued to pay great attention to Yemen. Governors were appointed directly by the caliph. During certain periods, Yemen was administratively grouped together with Hijaz and Yamama. Still, effective control over entire Yemen was not achieved. The land was threatened by the Kharijites of Oman and Bahrayn in 686-689, and was then taken by the Marwanid branch of the Umayyads in 692. In spite of the highly decentralized governance of their land, the Yemenis seldom rebelled against the Umayyads. The most serious revolt occurred at the end of the dynasty, in 745-747, during the Third Fitna. It was headed by a Kindi tribesman called Abdallah bin Yahya, known as Talib al-Haqq. He proclaimed himself caliph in Hadramawt, San'a, Mecca, and Medina. He was defeated in 747, but as a result the Ibadiyyah group in Hadramawt obtained the right to choose their own governors for a while.[4]

Abbasid Caliphs (750-897)

This is the dynastic name generally given to the caliphs of Baghdad, the second of the two great Sunni dynasties of the Arab Empire. The Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad caliphs from all their lands except Spain. The Abbasids continued the policy of the Umayyads with respect to Yemen. Frequently, a member of the highest Abbasid aristocracy, including princes of the dynasty, served as governors. But Yemen remained fragmented: the historian al-Yaqubi (d. 897) speaks of 84 provinces and a large number of tribes. Activities of the Alids threatened the Abbasid hold over Yemen. Ibrahim ibn Musa al-Kazim, brother of the well-known Alid Ali ar-Ridha, occupied San'a and the highlands in 815 and struck coins in his own name. He was, however, soon defeated by the troops of Caliph al-Ma'mun. Nevertheless, after the caliph had reached an understanding with the Alids, the same Ibrahim ibn Musa was appointed governor of Mecca and Yemen. San'a remained under the control of the caliph for some time. In the course of the 9th century, however, the power of the Abbasids over various fringe areas waned. Local Yemeni dynasties began to appear, either opposed to the Abbasids or acknowledging them.[5]

Yemeni textiles, long recognized for their fine quality, maintained their reputation and were exported for use by the Abbasid elite, including the caliphs themselves. The products of San'a and Aden have been particularly important in the East-West textile trade.

Ziyadids (818-1018)

In 817 the Caliph al-Ma'mun appointed the Umayyad Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Ziyad to restore order in the turbulent Yemeni lands. Ibn Ziyad established his power in the coastal area in the west (Tihama), and founded Zabid as its capital. The Ziyadids, as his family was called, were able to extend their influence over the most of Yemen, including Hadramawt and at least part of the highlands. All the while they recognized the Abbasid and observed Sunni religious practices. However, they had to contend with the Yufirids who dominated parts of the highland after 847, and Ismaili activities.

In 897 a new regime, or rather a religious branch, was established in highland Yemen with the centre in Sa'dah; it would play a major role in future Yemeni history. This was the Zaydiyyah movement led by the imam al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya (d. 911), a descendant of Muhammad. The Zaydi imams developed a peculiar brand of Shia Islam. The Zaydis spread their influence throughout the highland tribes through the sacred enclaves (janad) that were a part of local society. The imamate of the Zaydis was led by various descendants of Muhammad, mostly relatives of al-Hadi, but was not actually hereditary (before 1597). Zaydiyyah stressed the role of an active imam with political and religious qualifications. Internal struggles between claimants for the position of imam were common. Meanwhile, the Ziyadids in Zabid became increasingly dominated by African slave regents in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. They were eventually deposed by a powerful minister in 1018.[6]

Najahids (1022-1158)

The Najahids were Ethiopians with slave origins. Like the Ziyadids, they ruled from Zabid in the Tihama and were loyal to Sunni Islam, formally recognizing the caliph in distant Baghdad. However, their area of power was smaller than that of the Ziyadids, and their history was rather chequered. For some periods they were eclipsed by the highland dynasty of the Sulayhids. In the 12th century the reigning members of the dynasty became increasingly ineffective, and ministers ruled from behind the throne. In 1151 and later a series of raids by the aggressive Sunni movement of the Mahdids devastated the Tihama. The Mahdids managed to assassinate the last Najahid strongman Surur in 1156, which sealed the fate of the regime. Eventually Zabid fell and the Najahid dynasty was eliminated due to a combination of intervention by the Zaydi imam and a vigorous assault by the Mahdids.[7]

Sulayhids (1047-1138)

The Sulayhids, unlike the aforementioned regimes, were native Yemenis. The founder of the regime was Ali as-Sulayhi (d. 1067) who propagated Ismaili doctrines and established a state in the highlands in 1047. He took the Tihama lowland from the Najahids in 1060 and subjugated the important coastal entrepôt Aden. Ali as-Sulayhi formally ruled in the name of the Fatimid caliph in Cairo. He was murdered by the Najahids in 1067 or 1081, but his mission was continued by his son al-Mukarram Ahmad (d. 1091) and the latter's widow as-Sayyidah Arwa (d. 1138). Arwa is one of the few female rulers in the Islamic history of Arabia, and is praised in the sources for her piety, bravery, intelligence, and cultural interests. The dynasty ruled first from San'a and later Dhu Jibla. Sulayhid rule meant a nadir for the Zaydiyyah imamate, which did not bring forth any fully recognized imams from 1052 to 1138. The Sulayhids died out in 1138 with Queen Arwa. Their position in San'a was taken over for a while by the Hamdanid sultans (until 1174).[8]

Zurayids (1083-1174)

Al-Abbas and al-Mas'ūd, sons of Karam Al-Yami from the Hamdan tribe, started ruling Aden on behalf of the Sulayhids. When Al-Abbas died in 1083, his son Zuray, who gave the dynasty its name, proceeded to rule together with his uncle al-Mas'ūd. They took part in the Sulayhid leader al-Mufaddal's campaign against the Najahid capital Zabid and were both killed during the siege (1110).[9] Their respective sons ceased to pay tribute to the Sulayhid queen Arwa al-Sulayhi.[10] They were worsted by a Sulayhid expedition but queen Arwa agreed to reduce the tribute by half, to 50,000 dinars per year. The Zurayids again failed to pay and were once again forced to yield to the might of the Sulayhids, but this time the annual tribute from the incomes of Aden was reduced to 25,000. Later on they ceased to pay even that since Sulayhid power was on the wane.[11] After 1110 the Zurayids thus led a more than 60 years long independent rule in the city, bolstered by the international trade. The chronicles mention luxury goods such as textiles, perfume and porcelain, coming from places like North Africa, Egypt, Iraq, Oman, Kirman and China. After the demise of queen Arwa al-Sulayhi in 1138, the Fatimids in Cairo kept a representation in Aden, adding further prestige to the Zurayids.[12] The Zurayids were sacked by the Ayyubids in 1174 AD.

Ayyubids (1174–1229)

The importance of Yemen as a station in the trade between Egypt and the Indian Ocean area, and its strategical value, motivated the Ayyubid invasion in 1174. The Ayyubid forces were led by Turanshah, a brother of Sultan Saladin. The enterprise was entirely successful: the various local Yemeni dynasties, mainly the Zurayids were defeated or submitted, thus bringing an end to the fragmented political landscape. The efficient military might of the Ayyubids meant that they were not seriously threatened by local regimes during 55 years in power. The only disturbing element was the Zaydi imam who was active for part of the period. After 1217 the imamate was split, however. Members of the Ayyubid Dynasty were appointed to rule Yemen up to 1229, but they were often absent from the country, a factor that finally led to them being superseded by the following regime, the Rasulids. On the positive side, the Ayyubids united the bulk of Yemen in a way that had hardly been achieved before. The system of fiefs used in the Ayyubid core area was introduced to Yemen. The policies of the Ayyubids led to a bipartition that has lasted ever since: the coast and southern highlands dominated by Sunni and adhering to the Shafi'i school of law; and the upper highlands with a population mainly adhering to the Zaydiyyah. Ayyubid rule was therefore an important stepping-stone for he next dynastic regime.[13]

Rasulids (1229–1454)

The Rasulid dynasty, or Bani Rasul, were soldiers of Turkoman origins who served the Ayyubids. When the last Ayyubid ruler left Yemen in 1229 he appointed a member of Bani Rasul, Nur ad-Din Umar, as his deputy. He was later able to secure an independent position in Yemen and was recognized as sultan in his own right by the Abbasid Caliph in 1235. He and his descendants drew their methods of governance from the structures set up by the Ayyubids. Their capitals were Zabid and Ta'izz. For the first time, most of Yemen became a strong and independent political, economic, and cultural unit. The state was even able to contend with the Ayyubids and later the Mamluks over influence in Hijaz. The south Arabian coast was subdued in 1278-79. The Rasulids in fact created the strongest Yemeni state during the medieval Islamic era. Among the numerous medieval polities it was the one that endured for the longest period, and enjoyed the widest influence. Its impact in terms of administration and culture was stronger than the preceding regimes, and the interests of the Rasulid rulers covered all the affairs prevalent in those times.[14]

Some of the sultans had strong scientific interests and were skilled in astrology, medicine, agriculture, linguistics, legislation, etc. They built mosques, houses and citadels, roads and water channels. Rasulid projects extended as far as Mecca. The Sunnization of the land was intensified and madrasas were built everywhere. The flourishing trade gave the sultans great incomes which bolstered their regime. In the highlands the Zaydiyyah were initially pushed back by the Rasulid might. Nevertheless, after the late 13th century a succession of imams were able to build up a strong position and expand their influence. As for the Rasulid regime it was upheld by a long series of very gifted sultans. However, the polity began to decline in the 14th century, and especially after 1424. From 1442 to 1454 a number of rival claimants competed for the throne, which led to the downfall of the dynasty in the latter year.[15]

Tahirids (1454-1517)

The Bani Tahir was a powerful native Yemeni family which took advantage of the weakness of the Rasulids and finally gained power in 1454 as the Tahirids. In many respects the new regime tried to imitate the Bani Rasul whose institutions they took over. Thus they built schools, mosques and irrigation channels as well as water cisterns and bridges in Zabid, Aden, Yafrus, Rada, Juban, etc. Politically the Tahirids did not have ambitions to expand beyond Yemen itself. The sultans fought the Zaydi imams for periods, with varying success. They were never able to occupy the highlands entirely.[16] The Mamluk regime in Egypt began to dispatch seaborne expeditions towards the south after 1507, since the presence of the Portuguese constituted a threat in the southern Red Sea region. At first the Tahirid sultan Amir II supported the Mamluks, but later refused to assist them. As a consequence he was attacked and killed by a Mamluk force in 1517. Tahirid resistance leaders continued to disturb the Mamluk occupiers until 1538. As it turned out, the Tahirids were the last Sunni dynasty to rule in Yemen.[17]

First Ottoman period (1538-1635)

Now, the coast and southern highlands were suddenly left without a central government for the first time in almost 350 years. Shortly after the Mamluk conquest in 1517, Egypt itself was conquered by the Ottoman sultan Selim I. The Egyptian garrison in Yemen was cornered in a minor part of the Tihama, and the Zaydi imam expanded his territory. The Mamluk militaries formally recognized the Ottomans until 1538, when regular Turkish forces arrived. At this time the Ottomans began to worry about the Portuguese who occupied Socotra Island. The Ottomans eliminated the last Tahirid lord in Aden and the Mamluk military leadership, and set up an administration based in Zabid. Yemen was made a province (Beylerbeylik). The Portuguese blockade of the Red Sea was broken. A number of campaigns against the Zaydis were fought in 1539-56, and Sana'a was taken in 1547. Turkish misrule led to a large rebellion in 1568. The Zaydi imam put up a stubborn fight against the invaders who were almost expelled from Yemeni soil. Resistance was overcome in a new campaign in 1569-71. After the death of imam al-Mutahhar in 1572, the highlands were occupied by the Turkish troops. The first Turkish occupation lasted until 1635. The new lords promoted Sufis and Ismailis as a counterweight to the Zaydiyyah. However, Yemen was too far removed to be managed efficaciously. Over-taxation and unjust and cruel practices caused deep popular antipathy against foreign rule. The Zaydis accused the Ottomans of being "infidels of interpretation" and appointed a new imam in 1597, al-Mansur al-Qasim. In accordance with the doctrine that an imam must make a summons to allegiance (da'wa) and rebel against illegitimate rulers, Imam al-Mansur and his successor expanded their territory at the expense of the Turks who eventually had to leave their last possessions in 1635.[18]

Qasimids (1597-1872)

The imam al-Mansur al-Qasim (r. 1597-1620) belonged to one the branches of the Rassid (descendants of the first imam or his close family). The new line became known as the Qasimids after its founder. Al-Mansur's son al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad (r. 1620-1644) managed to gather Yemen under his authority, expel the Turks, and established an independent political entity. His successor al-Mutawakkil Isma'il (r. 1644-1676) subdued Hadramawt and entertained diplomatic contacts with the negus of Ethiopia and the Mughal emperor Aurangzib. He also reinstated the common annual pilgrimage caravans to Mecca, trying to inspire a sense of unity between Sunni and Shi'a Muslims. For a time, the imams ruled a comprehensive territory, from Asir in the north to Aden in the south, and to Dhofar in the far east. The centre of the imamic state was San'a, although the imams also used other places of residence such as ash-Shahara and al-Mawahib.[19] Its economic base was strengthened by the coffee trade of the coastal entrepot Mocha. Coffee had been introduced from Ethiopia in about 1543, and Yemen held a monopoly on this product for a long time. Merchants from Gujarat frequented Yemen after the withdrawal of the Turks, and European traders established factories after 1618. The first five imams ruled from strict Zaydi precepts, but unlike in the previous practice the Qasimids in fact succeeded each other as in a hereditary dynasty. Their state became institutionalized by the time, since Ottoman-style administration was applied, a standing army was kept, and a chief judge appointed. Most of the provinces were governed by members of the Qasimid family. Provincial rulers performed bay'ah (ritual homage) at their accession, but their fiefs became increasingly autonomous by the time.

The power of the imamate declined in the 18th and 19th century for a number of reasons. Politically it was never entirely stable since clashes between Qasimid branches occurred with some frequency and succession to the imamate was often contested. Adding to this, theological differences surfaced in the 18th century, since the Qasimids practiced ijtihad (legal reinterpretations) and were accused of illicit innovations (bidah). Tribal risings were common and the territory controlled by the imams shrank successively after the late 17th century. The Yafa tribe of South Yemen fell away in 1681 and Aden broke loose in 1731. The lucrative coffee trade declined in the 18th century with new producers in other parts of the world. This deprived the imams of their main external income. The Qasimid state has been characterized as a "quasi-state" with an inherent tension between tribes and government, and between tribal culture and learned Islamic morality. The imams themselves adopted the style of Middle East monarchies, becoming increasingly distant figures. As a result, they eventually lost their charismatic and spiritual position among the tribes of Yemen. The weakening of the imamic state became increasingly acute in the wake of the Wahhabi invasions, after 1800. Tihama was lost for long periods, being contested by lowland Arab chiefs and Egyptian forces. The imamate was further eclipsed by the second coming of the Turks to lowland Yemen in 1849, and to the highlands in 1872.[20]

Second Ottoman period (1872-1918)

Ottoman interest in Yemen was renewed in the mid-19th century. One aim was to increase Ottoman influence in the Red Sea trade, especially since the British occupied Aden since 1839. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 increased this incentive. The Tihama was occupied in 1849, but an expedition to San'a miscarried. Meanwhile, the period after 1849 saw a confused series of clashes between various claimants to the imamate in San'a and Sa'dah. The chaos played the Turks in the hands, and in 1872 a new expedition secured San'a with the cooperation of some Zaydi claimants. Nevertheless, claimant-imams continued to resist the Turkish efforts to govern Yemen, and only part of the country was effectively controlled. The modernization attempts of the late Ottoman Empire engendered dissatisfaction among strongly traditional circles, who branded such policies as un-Islamic.[21] An agreement with the rebellious imam Imam Yahya Hamidaddin was finally reached in 1911, whereby the latter was recognized as head of the Zaydis while the Turks collected taxes from their Sunni subjects. Meanwhile, Turkish and British interest clashed in Yemen. It was agreed in 1902 to demarcate the border between the respective spheres of interest, and an agreement was signed in 1914. This was the backdrop to the later division in two Yemeni states (up to 1990). By this time the Ottoman Empire had few years left to go. The dissolution of the empire after World War I led to a complete withdrawal in 1918.[22]

Mutawakkilite Kingdom (1904-1962)

After 1891 the Hamid ad-Din branch of the Qasimids lay claim to the imamate. In the early 20th century Imam Yahya scored significant successes against the Turkish forces, leading to the truce of 1911. During World War I Imam Yahya nominally adhered to the Ottomans, but was able to establish a fully independent state in 1918. It is known as the Mutawakkilite Kingdom after the laqab name of Imam Yahya, al-Mutawakkil. Yahya pacified the tribes of the Tihama with heavy-handed methods. He also tried unsuccessfully to incorporate Asir and Najran in his realm (1934). These regions were, however acquired by Saudi Arabia. South Yemen stayed under British control until 1967 when it became an independent state. Yahya enjoyed legitimacy among the Zaydi tribes of the inland, while the Sunni population of the coast and southern highlands were less inclined to accept his rule. In order to maintain power he acted as a hereditary king and appointed his own sons to govern the various provinces. Dissatisfied subjects, forming the Free Yemeni Movement, murdered Imam Yahya in 1948 with the aim to create a constitutional monarchy. However, his son Ahmad bin Yahya was able to take over power with the help of loyal tribal allies. He henceforth kept his court in Ta'izz rather than San'a.[23]

The conservative rule of the imam was challenged by the rise of Arab nationalism. Yemen adhered to the United Arab Republic proclaimed by Egyptian president Nasser in 1958, joining with Egypt and Syria in a loose coalition called the United Arab States. However, the imam withdrew when Syria left the union in 1961. Pro-Egyptian militaries began to plot against the ruler. When Ahmad bin Yahya died in 1962, his son Muhammad al-Badr was quickly deposed as the plotters took over San'a. The Yemen Arab Republic was proclaimed. Muhammad al-Badr managed to escape to the loyalists in the highlands, and a civil war followed. Saudi Arabia supported the imam while Egypt dispatched troops to prop up the republicans. After Egypt's defeat against Israel in 1967, and the formation of a socialist people's republic in South Yemen in the same year, both intervening powers tried to find a solution in order to have their hands free. An agreement was finally reached in 1970 where the royalists agreed to accept the Yemen Arab Republic in return for influence in the government.[24]

For developments after 1970, see the article Modern history of Yemen.

See also

References

- Original text from U.S. State Dept. Country Study

- (1): DAUM, W. (ed.): Yemen. 3000 years of art and civilisation in Arabia Felix., Innsbruck / Frankfurt am Main / Amsterdam [1988]. pp. 53–4.

- History of Yemen

- Yemenite Virtual Museum - excellent site with many pictures.

- A Dam at Marib

- Das Fenster zum Jemen (German)

- Geschichte des Jemen (German)

Citations

- ↑ Hugh Kennedy, The Prophet and the age of the Caliphates. Harlow: Pearson 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam, Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 415-6.

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam I, 2010, pp. 416-7

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam I, 2010, pp. 417-9.

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam I, 2010, pp. 419-421.

- ↑ H.C. Kay, Yaman: Its early medieval history. London: Edward Arnold 1892, pp. 1-18. https://archive.org/stream/yamanitsearlymed00umar#page/n5/mode/2up

- ↑ H.C. Kay 1892, pp. 81-123.

- ↑ H.C. Kay 1892, pp. 19-49.

- ↑ The chronology of the Zurayid rulers is uncertain for the most part; dates furnished by Ayman Fu'ad Sayyid, Masadir ta'rikh al-Yaman fial 'asr al-islami, al Qahira 1974, are partly at odds with those given by H.C. Kay, Yaman: Its early Medieval history, London 1892; one source seems to indicate that they were independent as early as 1087.

- ↑ H.C. Kay, Yaman: Its early medieval history, London 1892, pp. 66-7.

- ↑ El-Khazreji, The pearl-strings, Vol. 1, Leyden & London 1906, p. 19.

- ↑ Robert W. Stookey, Yemen: The politics of the Yemen Arab Republic, Boulder 1978, p. 96.

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam, Vol. II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010, p. 290.

- ↑ G. Rex Smith, The Ayyubids and early Rasulids in the Yemen, Vols. I-II, London: Gibb Memorial Trust 1974-1978.

- ↑ El-Khazraji, The pearl-strings: A history of the Resuliyy Dynasty of Yemen, Vols. I-V, Leiden & London: Brill & Luzac 1906-1918; The new Cambridge history of Islam II, 2010, pp. 290-1.

- ↑ Venetia Porter, The history and monuments of the Tahirid Dynasty of Yemen 858-923/1454-1517, PhD Thesis, Durham University, 1992, http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5867/1/5867_3282-vol1.PDF?UkUDh:CyT

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam II, 2010, p. 291.

- ↑ Michel Tuchscherer, 'Chronologie du Yemen (1506-1635)', Chroniques yéménites 8 2000, http://cy.revues.org/11 .

- ↑ Tomislav Klaric, 'Chronologie du Yémen (1045-1131/1635-1719)', Chroniques yémenites 9 2001, http://cy.revues.org/36 .

- ↑ Paul Dresch, Tribes, government, and history in Yemen, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1989, pp. 212-8.

- ↑ Caesar E. Farah, The Sultan's Yemen; Nineteenth-Century Challenges to Ottoman Rule. London: Tauris 2002.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the modern Middle East and North Africa, Vol, IV, Detroit: Thomson-Gale 2004, p. 2390; Paul Dresch, A history of modern Yemen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2000, pp. 4-7.

- ↑ Paul Dresch 2000, pp. 43-57.

- ↑ The new Cambridge history of Islam II, 2010, pp. 471-3.

Further reading

- Alessandro de Maigret. Arabia Felix, translated Rebecca Thompson. London: Stacey International, 2002. ISBN 1-900988-07-0

- Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-922237-1

- R.L. Playfair, A history of Arabia Felix or Yemen. Bombay: Education Society's Press 1859. https://books.google.com/books?id=i0oOAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=sv&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- R. Serjeant & R. Lewcock, San'a'; An Arabian Islamic City. London: World of Islam Festival Trust 1983.

- Robert W. Stookey, Yemen; The Politics of the Yemen Arab Republic. Boulder: Westview Press 1978.