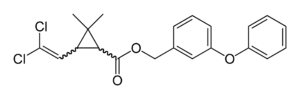

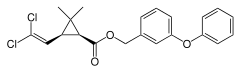

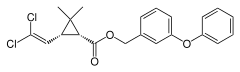

Permethrin

Chemical structure of permethrin | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nix, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.052.771 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H20Cl2O3 |

| Molar mass | 391.29 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.19 g/cm3, solid g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 34 °C (93 °F) |

| Boiling point | 200 °C (392 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 5.5 x 10−3 ppm mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

Permethrin, sold under the brand name Nix among others, is a medication and insecticide.[1][2] As a medication it is used to treat scabies and lice.[3] It is applied to the skin as a cream or lotion.[1] As an insecticide it can be sprayed on clothing or mosquito nets such that the insects that touch them die.[2]

Side effects include rash and irritation at the area of use.[3] Use during pregnancy appears to be safe. It is approved for use in people over the age of two months. Permethrin is in pyrethroid family of medications. It works by disrupting the function of the neurons of lice and scabies mites.[1]

Permethrin was discovered in 1973.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 0.02 to 0.06 USD per gram.[6] In the United States a course of treatment costs 25 to 50 USD and it is available over the counter.[7]

Uses

Permethrin is used:

- as an insecticide

- in agriculture, to protect crops (lethal for bees)

- in agriculture, to kill livestock parasites

- for industrial/domestic insect control

- in the textile industry to prevent insect attack of woollen products

- in aviation, the WHO, IHR and ICAO require arriving aircraft be disinsected prior to departure, descent or deplaning in certain countries

- to treat head lice in humans

- as an insect repellent or insect screen

- in timber treatment

- as a personal protective measure (cloth impregnant, used primarily for US military uniforms and mosquito nets)

- in pet flea preventative collars or treatment

- often in combination with piperonyl butoxide to enhance its effectiveness.

Medical use

Permethrin is available for topical use as a cream or lotion. It is indicated for the treatment and prevention in exposed individuals of head lice and treatment of scabies.[8]

For treatment of scabies: Adults and children older than 2 months are instructed to apply the cream to the entire body from head to the soles of the feet. Wash off the cream after 8–14 hours. In general, one treatment is curative.[9]

For treatment of head lice: Apply to hair, scalp, and neck after shampooing. Leave in for 10 minutes and rinse. Avoid contact with eyes.[10]

Pest control

In agriculture, permethrin is mainly used on cotton, wheat, maize, and alfalfa crops. Its use is controversial because, as a broad-spectrum chemical, it kills indiscriminately; as well as the intended pests, it can harm beneficial insects including honey bees, and aquatic life.[11]

Permethrin kills ticks and mosquitoes on contact with treated clothing. A method of reducing deer tick populations by treating rodent vectors involves stuffing biodegradable cardboard tubes with permethrin-treated cotton. Mice collect the cotton for lining their nests. Permethrin on the cotton instantly kills any immature ticks feeding on the mice.

Permethrin is used in tropical areas to prevent mosquito-borne disease such as dengue fever and malaria. Mosquito nets used to cover beds may be treated with a solution of permethrin. This increases the effectiveness of the bed net by killing parasitic insects before they are able to find gaps or holes in the net. Military personnel training in malaria-endemic areas may be instructed to treat their uniforms with permethrin, as well.

Permethrin is the most commonly used insecticide worldwide for the protection of wool from keratinophagous insects such as Tineola bisselliella.[12]

Side effects

Permethrin application can cause mild skin irritation and burning. Discontinue use if hypersensitivity occurs.

Safety

Permethrin has little systemic absorption, and is considered safe for topical use in adults and children over the age of 2 months. The FDA has assigned it as pregnancy category B. Animal studies have shown no effects on fertility or teratogenicity, but studies in humans have not been performed. The excretion of permethrin in breastmilk is unknown, and breastfeeding is recommended to be temporarily discontinued during treatment.[10]

According to the Connecticut Department of Public Health, permethrin "has low mammalian toxicity, is poorly absorbed through the skin, and is rapidly inactivated by the body. Skin reactions have been uncommon."[13]

Excessive exposure to permethrin can cause nausea, headache, muscle weakness, excessive salivation, shortness of breath, and seizures. Worker exposure to the chemical can be monitored by measurement of the urinary metabolites, while severe overdose may be confirmed by measurement of permethrin in serum or blood plasma.[14]

Permethrin does not present any notable genotoxicity or immunotoxicity in humans and farm animals, but is classified by the EPA as a likely human carcinogen, based on reproducible studies in which mice fed permethrin developed liver and lung tumors.[15]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Absorption of topical permethrin is minimal. One in vivo study demonstrated 0.5% absorption in the first 48 hours based upon excretion of urinary metabolites.[16]

Distribution

Distribution of permethrin has been studied in rat models, with highest amounts accumulating in fat and the brain.[17] This can be explained by the lipophilic nature of the permethrin molecule.

Metabolism

Metabolism of permethrin occurs mainly in the liver, where the molecule undergoes oxidation by the cytochrome P450 system, as well as hydrolysis, into metabolites.[16] Elimination of these metabolites occurs via urinary excretion.

Military use

To better protect soldiers from the risk and annoyance of biting insects, the US[18] and British[19] armies are treating all new uniforms with permethrin.

Stereochemistry

Permethrin has four stereoisomers (two enantiomeric pairs), arising from the two stereocenters in the cyclopropane ring. The trans enantiomeric pair is known as transpermethrin.

-trans-permethrin.svg.png) (1S,3R)-trans enantiomer

(1S,3R)-trans enantiomer-trans-permethrin.svg.png) (1R,3S)-trans enantiomer

(1R,3S)-trans enantiomer (1S,3S)-cis enantiomer

(1S,3S)-cis enantiomer (1R,3R)-cis enantiomer

(1R,3R)-cis enantiomer

History

Permethrin was first made in 1973.[20]

Numerous synthetic routes exist for the production of the DV-acid ester precursor. The pathway known as the Kuraray Process uses four steps.[21] In general, the final step in the total synthesis of any of the synthetic pyrethroids is a coupling of a DV-acid ester and an alcohol. In the case of permethrin synthesis, the DV-acid cyclopropanecarboxylic acid, 3-(2,2-dichloroethenyl)-2,2-dimethyl-, ethyl ester, is coupled with the alcohol, m-phenoxybenzyl alcohol, through a transesterification reaction with base. Tetraisopropyl titanate or sodium ethylate may be used as the base.[21]

The alcohol precursor may be prepared in three steps. First, m-cresol, chlorobenzene, sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and copper chloride react to yield m-phenoxytoluene. Second, oxidation of m-phenoxytoluene over selenium dioxide provides m-phenoxybenzaldehyde. Third, a Cannizzaro reaction of the benzaldehyde in formaldehyde and potassium hydroxide affords the m-phenoxybenzyl alcohol.[21]

Brand names

It is marketed by Johnson & Johnson under the name Lyclear. In Nordic countries and North America, it is marketed under trade name Nix, often available over the counter.

Other animals

Permethrin is listed as a "restricted use" substance by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)[22] due to its high toxicity to aquatic organisms,[23] so permethrin and permethrin-contaminated water should be properly disposed. Permethrin is quite stable, having a half life of 51–71 days in an aqueous environment exposed to light. It is also highly persistent in soil.[24]

Domestic animals

Pesticide-grade permethrin is toxic to cats. Many cats die after being given flea treatments intended for dogs, or by contact with dogs having recently been treated with permethrin.[25] In cats it may induce hyperexcitability, tremors, seizures, and death.[26]

Toxic exposure of permethrin can cause several symptoms, including convulsion, hyperaesthesia, hyperthermia, hypersalivation, and loss of balance and coordination. Exposure to pyrethroid-derived drugs such as permethrin requires treatment by a veterinarian, otherwise the poisoning is often fatal.[27][28] This intolerance is due to a defect in glucuronosyltransferase, a common detoxification enzyme in other mammals (that also makes the cat intolerant to paracetamol and many essential oils).[29] The use of any external parasiticides based on permethrin is contraindicated for cats. (Cat ecotoxicology : cutaneous 100 mg/kg - oral 200 mg/kg.)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Permethrin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Keystone, J. S.; Kozarsky, Phyllis E.; Freedman, David O.; Connor, Bradley A. (2013). Travel Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 58. ISBN 1455710768.

- 1 2 WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 213. ISBN 9789241547659. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Zweig, Gunter; Sherma, Joseph (2013). Synthetic Pyrethroids and Other Pesticides: Analytical Methods for Pesticides and Plant Growth Regulators. Academic Press. p. 104. ISBN 9781483220901.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Permethrin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 182. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ "Permethrin (Lexi-Drugs)". Lexicomp Online. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "Permethrin Patient Package Insert" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Package Label" (PDF). Alpharma, USPD, Inc. Baltimore. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ R. H. Ian (1989). "Aquatic organisms and pyrethroids". Pesticide Science. 27 (4): 429–457. doi:10.1002/ps.2780270408.

- ↑ Ingham P. E.; McNeil S. J.; Sunderland M. R. (2012). "Functional finishes for wool – Eco considerations". Advanced Materials Research. 441: 33–43. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.441.33.

- ↑ Kirby C. Stafford III (February 1999). "Tick Bite Prevention". Connecticut Department of Public Health.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1215–1216.

- ↑ Permethrin Facts, US EPA, June 2006.

- 1 2 van der Rhee, HJ; Farquhar, JA; Vermeulen, NP (1989). "Efficacy and transdermal absorption of permethrin in scabies patients.". Acta dermato-venereologica. 69 (2): 170–3. PMID 2564238.

- ↑ Tornero-Velez, R; Davis, J; Scollon, EJ; Starr, JM; Setzer, RW; Goldsmith, MR; Chang, DT; Xue, J; Zartarian, V; DeVito, MJ; Hughes, MF (Nov 2012). "A pharmacokinetic model of cis- and trans-permethrin disposition in rats and humans with aggregate exposure application.". Toxicological Sciences. 130 (1): 33–47. PMID 22859315. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfs236.

- ↑ Insect-repelling ACUs now available to all Soldiers, United States Army, Canadian and

- ↑ Personal Clothing - British Army Website, What's In The Black Bag? Accessed 14 October 2015

- ↑ Elliott, M; Farnham, AW; Janes, NF; Needham, PH; Pulman, DA; Stevenson, JH (16 November 1973). "A photostable pyrethroid.". Nature. 246 (5429): 169–70. PMID 4586114.

- 1 2 3 Leonard A. Wasselle, "Pyrethroid Insecticides." SRI International Report #143, Menlo Park, CA, 94025, June 1981.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency. "Restricted Use Products (RUP) Report: Six Month Summary List". Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency. "Permethrin Facts (RED Fact Sheet)". Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ↑ Heather Imgrund (January 28, 2003). "Environmental Fate of Permethrin" (PDF). Environmental Monitoring Branch, California Department of Pesticide Regulation, California Environmental Protection Agency.

- ↑ Linnett, P.-J. (2008). "Permethrin toxicosis in cats". Australian Veterinary Journal. 86 (1–2): 32–35. PMID 18271821. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2007.00198.x.

- ↑ Stephen W. Page (2008). "10: Antiparasitic drugs". In Jill E. Maddison. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Stephen W. Page, David Church. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 236. ISBN 0-7020-2858-4. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ http://www.aspcapro.org/sites/pro/files/d-veccs_april00.pdf

- ↑ Dymond NL, Swift IM (2008). "Permethrin toxicity in cats: a retrospective study of 20 cases.". nih.gov. 86: 219–23. PMID 18498556. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2008.00298.x.

- ↑ http://www.depecheveterinaire.com/basedocudv/actualites_dermatologiques_etude_retrospective_australienne_signes_nerveux_digestifs.pdf

External links

- Permethrin in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- Permethrin Technical Fact Sheet – National Pesticide Information Center

- Permethrin General Fact Sheet – National Pesticide Information Center

- Permethrin-treated Clothing Hot Topic – National Pesticide Information Center

- "Health Effects of Permethrin-Impregnated Army Battle-Dress Uniforms", National Research Council (1994, US)

- "Permethrin summary report", Committee for Veterinary Products, European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical Products (1998, EU)

- Permethrin Pesticide Information Profile – Extension Toxicology Network

- Permethrin chemical data