Faraday cage

A Faraday cage or Faraday shield is an enclosure used to block electromagnetic fields. A Faraday shield may be formed by a continuous covering of conductive material or in the case of a Faraday cage, by a mesh of such materials. Faraday cages are named after the English scientist Michael Faraday, who invented them in 1836.[1]

A Faraday cage operates because an external electrical field causes the electric charges within the cage's conducting material to be distributed such that they cancel the field's effect in the cage's interior. This phenomenon is used to protect sensitive electronic equipment from external radio frequency interference (RFI). Faraday cages are also used to enclose devices that produce RFI, such as radio transmitters, to prevent their radio waves from interfering with other nearby equipment. They are also used to protect people and equipment against actual electric currents such as lightning strikes and electrostatic discharges, since the enclosing cage conducts current around the outside of the enclosed space and none passes through the interior.

Faraday cages cannot block stable or slowly varying magnetic fields, such as the Earth's magnetic field (a compass will still work inside). To a large degree, though, they shield the interior from external electromagnetic radiation if the conductor is thick enough and any holes are significantly smaller than the wavelength of the radiation. For example, certain computer forensic test procedures of electronic systems that require an environment free of electromagnetic interference can be carried out within a screened room. These rooms are spaces that are completely enclosed by one or more layers of a fine metal mesh or perforated sheet metal. The metal layers are grounded to dissipate any electric currents generated from external or internal electromagnetic fields, and thus they block a large amount of the electromagnetic interference. See also electromagnetic shielding. They provide less attenuation from outgoing transmissions versus incoming: they can shield EMP waves from natural phenomena very effectively, but a tracking device, especially in upper frequencies, may be able to penetrate from within the cage (e.g., some cell phones operate at various radio frequencies so while one cell phone may not work, another one will).

A common misconception is that a Faraday cage provides full blockage or attenuation; this is not true. The reception or transmission of radio waves, a form of electromagnetic radiation, to or from an antenna within a Faraday cage is heavily attenuated or blocked by the cage, however, a Faraday cage has varied attenuation depending on wave form, frequency or distance from receiver/transmitter, and receiver/transmitter power. Near-field high-powered frequency transmissions like HF RFID are more likely to penetrate. Solid cages generally provide better attenuation than mesh cages.

History

In 1836, Michael Faraday observed that the excess charge on a charged conductor resided only on its exterior and had no influence on anything enclosed within it. To demonstrate this fact, he built a room coated with metal foil and allowed high-voltage discharges from an electrostatic generator to strike the outside of the room. He used an electroscope to show that there was no electric charge present on the inside of the room's walls.

Although this cage effect has been attributed to Michael Faraday's famous ice pail experiments performed in 1843, it was Benjamin Franklin in 1755 who observed the effect by lowering an uncharged cork ball suspended on a silk thread through an opening in an electrically charged metal can. In his words, "the cork was not attracted to the inside of the can as it would have been to the outside, and though it touched the bottom, yet when drawn out it was not found to be electrified (charged) by that touch, as it would have been by touching the outside. The fact is singular." Franklin had discovered the behavior of what we now refer to as a Faraday cage or shield (based on Faraday's later experiments which duplicated Franklin's cork and can).[2] Additionally, Giovanni Battista Beccaria discovered this effect a long time before Faraday too.[3]

Operation

Continuous

A continuous Faraday shield is a hollow conductor. Externally or internally applied electromagnetic fields produce forces on the charge carriers (usually electrons) within the conductor; the charges are redistributed accordingly due to electrostatic induction. The redistributed charges greatly reduce the voltage within the surface, to an extent depending on the capacitance, however, full cancellation does not occur.[4]

Interior charges

If a charge is placed inside an ungrounded Faraday cage, the internal face of the cage becomes charged (in the same manner described for an external charge) to prevent the existence of a field inside the body of the cage, however, this charging of the inner face re-distributes the charges in the body of the cage. This charges the outer face of the cage with a charge equal in sign and magnitude to the one placed inside the cage. Since the internal charge and the inner face cancel each other out, the spread of charges on the outer face is not affected by the position of the internal charge inside the cage. So for all intents and purposes, the cage generates the same DC electric field that it would generate if it were simply affected by the charge placed inside. The same is not true for electromagnetic waves.

If the cage is grounded, the excess charges will go to the ground instead of the outer face, so the inner face and the inner charge will cancel each other out and the rest of the cage will retain a neutral charge.

Exterior fields

- Mn-Zn – magnetically soft ferrite

- Al – metallic aluminum

- Cu – metallic copper

- steel 410 – magnetic stainless steel

- Fe-Si – grain-oriented electrical steel

- Fe-Ni – high-permeability permalloy (80%Ni-20%Fe)

Effectiveness of shielding of a static electric field is largely independent of the geometry of the conductive material, however, static magnetic fields can penetrate the shield completely.

In the case of a varying electromagnetic fields, the faster the variations are (i.e., the higher the frequencies), the better the material resists magnetic field penetration. In this case the shielding also depends on the electrical conductivity, the magnetic properties of the conductive materials used in the cages, as well as their thicknesses.

A good idea of the effectiveness of a Faraday shield can be obtained from considerations of skin depth. With skin depth, the current flowing is mostly in the surface, and decays exponentially with depth through the material. Because a Faraday shield has finite thickness, this determines how well the shield works; a thicker shield can attenuate electromagnetic fields better, and to a lower frequency.

Faraday cage

Faraday cages are Faraday shields which have holes in the conductor and are more complex to analyze. Whereas continuous shields essentially attenuate all frequencies above the skin depth, the holes in a cage can permit higher frequencies to diffract through them or set up evanescent waves a short distance inside the surface. The higher the frequencies, the better they pass through a mesh of given size. Thus to work well at high frequencies the holes in the cage must be smaller than the wavelength of the incident EM wave, and Faraday cages may be thought of as band block devices.

Examples

- Faraday cages are routinely used in analytical chemistry to reduce noise while making sensitive measurements.

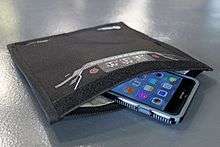

- Faraday cages, more specifically dual paired seam Faraday bags, are often used in digital forensics to prevent remote wiping and alteration of criminal digital evidence.

- The US and NATO Tempest standards, and similar standards in other countries, include Faraday cages as part of a broader effort to provide emission security for computers.

- Automobile and airplane passenger compartments are essentially Faraday cages, protecting passengers from electric charges, such as lightning

- A booster bag (shopping bag lined with aluminium foil) acts as a Faraday cage. It is often used by shoplifters to steal RFID-tagged items.[5]

- Similar containers are used to resist RFID skimming.

- Elevators and other rooms with metallic conducting frames and walls simulate a Faraday cage effect, leading to a loss of signal and "dead zones" for users of cellular phones, radios, and other electronic devices that require external electromagnetic signals. During training firemen and other first responders are cautioned that their two-way radios will probably not work inside elevator cars and to make allowances for that. Small, physical Faraday cages are used by electronics engineers during equipment testing to simulate such an environment to make sure that the device gracefully handles these conditions.

- Properly designed conductive clothing can also form a protective Faraday cage. Some electrical linemen wear Faraday suits, which allow them to work on live, high-voltage power lines without risk of electrocution. The suit prevents electric current from flowing through the body, and has no theoretical voltage limit. Linemen have successfully worked even the highest voltage (Kazakhstan's Ekibastuz–Kokshetau line 1150 kV) lines safely.

- Austin Richards, a physicist in California, created a metal Faraday suit in 1997 that protects him from tesla coil discharges. In 1998, he named the character in the suit Doctor MegaVolt and has performed all over the world and at Burning Man nine different years.

- The scan room of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine is designed as a Faraday cage. This prevents external RF (radio frequency) signals from being added to data collected from the patient, which would affect the resulting image. Radiographers are trained to identify the characteristic artifacts created on images should the Faraday cage be damaged during a thunderstorm.

- A microwave oven utilizes a Faraday cage, which can be partly seen covering the transparent window, to contain the electromagnetic energy within the oven and to shield the exterior from radiation.

- Plastic bags that are impregnated with metal are used to enclose electronic toll collection devices during shipment to the customer, so that a toll charge is not registered if the delivery truck carrying the item passes through a toll booth.

- The shield of a screened cable, such as USB cables or the coaxial cable used for cable television, protects the internal conductors from external electrical noise and prevents the RF signals from leaking out.

See also

- Anechoic chamber

- Anti-static bag

- Conductive textile

- Electromagnetic field

- Electromagnetic interference

- Foil hat

- Gauss's law

- Mu-metal

- Mylar blanket

References

- ↑ "Michael Faraday". Encarta. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ J. D. Krauss, Electromagnetics, 4Ed, McGraw-Hill, 1992, ISBN 0-07-035621-1

- ↑ "The Annals of Electricity, Magnetism, and Chemistry; and Guardian of Experimental Science". 1 January 1840 – via Google Books.

- ↑ https://people.maths.ox.ac.uk/trefethen/chapman_hewett_trefethen.pdf Mathematics of the Faraday Cage- S. Jonathan Chapman David P. Hewett Lloyd N. Trefethen

- ↑ Hamill, Sean (22 December 2008). "As Economy Dips, Arrests for Shoplifting Soar". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Faraday cages. |

- Faraday Cage Protects from 100,000 V :: Physikshow Uni Bonn

- Notes from physics lecture on Faraday cages from Michigan State University

- Michael Faraday: The Invention of Faraday Cage background and related experiment

- Top Gear's Richard Hammond is protected from 600,000 V by a car (a Faraday Cage).

- Top Gear's Richard Hammond as a human lightning rod - protected by a Voltrex Suit

- The Faraday Cage: What Is It? How Does It Work?