Elcor, Minnesota

| Elcor, Minnesota | |

|---|---|

| Ghost town | |

Elcor, Minnesota | |

| Coordinates: 47°30′19″N 92°26′28″W / 47.50528°N 92.44111°WCoordinates: 47°30′19″N 92°26′28″W / 47.50528°N 92.44111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

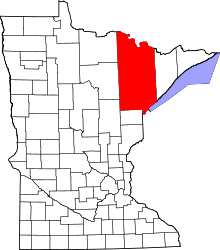

| County | Saint Louis |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| Area code(s) | 218 |

| GNIS feature ID | 661197[1] |

Elcor is a ghost town, or more properly, an extinct town on the eastern end of the Mesabi Iron Range, near the city of Gilbert in Saint Louis County, Minnesota, United States. An unincorporated community before it was abandoned, Elcor was never a neighborhood proper of the city of Gilbert,[2] but the area where Elcor was located was annexed by the city of Gilbert when the existing city boundaries were expanded after 1969.[3] The people of Elcor were only generally considered to be citizens of Gilbert.[4]

Geology

Elcor was located on a bed of taconite consisting of a uniform mixture of about 30% iron, interspersed with pockets of high grade ore, a part of the Biwabik iron formation, a great sheet of iron-bearing sediment deposited during the Precambrian era on the bottom of a large body of water called the Animikie Sea. This iron-bearing rock extends under Lake Superior from the Mesabi and Vermilion Iron Range on the north, south to the Gogebic Iron Range extending from northern Wisconsin into the Marquette Range of the upper peninsula of Michigan, and west to the manganese rich ore of the Cuyuna Iron Range.[5] Michigan’s steel-blue high grade ores were quite different from those on the Mesabi, which was soft brown hematite.[6] Iron is also located in other areas of Minnesota, but in quantities that are no longer practical to mine.[7]

Geologists divide the iron-bearing rocks of the eastern Mesabi Iron Range into several layers: its four main divisions from the top down are named the Upper Slaty, Upper Cherty, Lower Slaty and Lower Cherty. Below these are quartzite and granite and the top is Virginia Slate and Duluth Gabbro. The Slate is from fifty to several hundred feet thick, and below this the four iron-bearing members are from four hundred to six hundred feet thick.[8]

Geography and Climate

Elcor was located in the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province in the Arrowhead region of northern Minnesota.[9] The polar air mass dominates this part of the state year-round. Precipitation ranges from about 21 inches (53 cm) annually along the western border of the forest to about 32 inches (81 cm) at its eastern edge in Minnesota. Normal annual temperatures are about 34 °F (1 °C) along the northern part of the forest in Minnesota, rising to 40 °F (4 °C) at its southern extreme.

July is the warmest month, when the average high temperature is 78 °F (26 °C) and the average low is 51 °F (11 °C). January is the coldest month, where the average high temperature is 18 °F (-8 °C) and the average low temperature is -5 °F (-21 °C). Elcor was situated approximately 22 miles (35 km) south-southwest of Tower, Minnesota where the record low temperature of -60 °F (-51 °C) was set on February 2, 1996.[10]

History

Establishment

The community of Elcor, which began with the opening of the Elba mine in 1897 ended with the closing of the Corsica mine in 1954.[11][12][13] Elcor was originally known as the Elba location, located between the present day cities of McKinley and Gilbert.[2][14][15] Elcor was an Iron Range mining location – a grid of houses the mining company originally rented to its employees.[16] Elcor was one of nearly 50 mining locations located between the present day cities of Eveleth and Aurora.[17] Some of these locations, like Sparta[18][19][20][21][22][23] and Pineville,[11][12][24] still exist today; others, such as Belgrade[25] and Genoa,[26][27][28][29] have been annexed by adjacent communities. Most have disappeared entirely.

The community was first called “Elba”, after the name of the first underground mine there. A second underground mine, the Corsica, opened a few years later.[16] The history of Elcor dates back to 1897, when the Elba mine was put into operation. With the opening of the mine, “Elba location” came into being.[15][31]

Development of the Elba mine was carried out by the Minnesota Iron Company and the first shipment of ore was made in 1898.[14][15][32] The Corsica mine was owned by Petit and Robinson and the first shipment of ore was made in 1901.[2][14][32] Don H. Bacon, who joined the Minnesota Iron Company as general manager in 1887 and eventually became its president, was a classical-minded man and ardent traveler who named many mines after Mediterranean islands: Malta, Maiorica, Corsica, Elba and the like. He had a penchant for naming things with the letter “M”. The Minnesota Steamship Company was organized in 1889 to carry ore for the Minnesota Iron Company; it was called the “M” fleet. Its steamers were the Mariska (which also shared the name of an open pit mine near Gilbert), Maruba, Manola and Matoa (both beached in the Great Lakes Storm of 1913),[33] Marina, Masaba, Maritana, Mariposa, Maricopa and later the Mataafa, after which the Lake Superior storm, the Mataafa Blow was named; its barges were the Magna (from the Latin meaning "large" or "great"), Manda, Martha, Maia, Malta, Marcia and Maida. Consequently, all of the streets and avenues platted in Elcor began with “M’s":[6][34]

Mohawk Street

Malta Street

Manilla Street (this was also the main street)

Manola Street

Mariposa Avenue

Mauna Loa Avenue

Maritana Avenue

Minorca Avenue

The first street in “Elba” was Manilla Street and company houses were constructed on both sides of it.[35]

The Elba group of mines was located from one to one and one-half miles west of McKinley, and was usually classed with the McKinley district.[36] The Elba mine was operated by the Minnesota Iron Company from 1898 to 1900 under the direction of M.E. McCarthy. Immediately after the formation of the United States Steel Corporation, Pickands Mather and Company leased the Elba and Corsica mines, operating both mines after that date.[13][14][37] Owners James Pickands, Samuel Mather and Jay Morse had been interested in the Corsica iron ore properties for some time, and the mines remained on the firm's shipping roll for many years.[32] William Philip Chinn was appointed superintendent of the Elba and adjacent Corsica mine under the new management of Pickands Mather and Company, succeeding McCarthy.[14][38] Mr. Chinn was then on his way up in mining circles, becoming general manager of all Pickands Mather mining properties in the Lake Superior region in 1918. He was succeeded as superintendent of the Elba and Corsica mines by Mr. L.C. David.[13][38][39]The Oliver Iron Mining Company also owned what was designated by them the "Elba No. 1 and No. 2 Reserve" ore bodies, but these were entirely different from the Elba and Corsica mines and remained undeveloped.[37]

The location community grew at the beginning of the century.[14] In 1902, the Corsica mine began operating in earnest and houses began mushrooming everywhere.[40] Company houses were built among the tall timbers. The community thrived on iron mining, its population flirting with 1,000 after World War I,[16] resulting in a neat and comfortable location comprising more than 100 houses.[36] The townspeople were hardy pioneers and a jumble of nationalities, bringing in a mixture of groups, including Croatians, Slovenians, Finns, Italians, Germans, Scandinavians and English, particularly from Cornwall.[2][41][14][16][42][43] The communication system between the different ethnicities and the respect they had for each other was truly remarkable.[44]

In the early days, houses were wooden boards fronted by a 4-board high fence which was fronted with a boardwalk. Most of the streets were just dirt roads.[34] Winters were bitterly cold, and when streets had to be plowed, a team of horses dragging a V-shaped wooden plow cleared the streets.[45][31] Located in the center of town was the community pump from which the village would draw water at stipulated hours. Water was pumped from the mine twice a day from a big open pipe. Everyone had to carry water home during pumping time to facilitate the day’s needs. There was no shut off valve, so everyone had to get busy with buckets, tubs, and barrels so that there would be enough water to "tide over".[2][14][46][34] Later, water came from a deep well when a water tower was built. St. Bernard dogs were used to help carry the water from the well to the homes. Running water and bathtubs did not come for many years, until ditches were dug for pipes to provide water from Gilbert in about 1915 or 1916.[14][34] Kerosene lamps provided the means of lighting until 1916 when power lines were installed.[46][34] The only telephone initially was at the Elba mine office.[47]

The Finns of the community organized a temperance society and in a joint effort built the Finnish Temperance Hall.[48] The community also included a band, a volunteer fire department, tennis courts, and a club house erected for use of the employees.[49][14][36] A small Methodist Church and Presbyterian Church were built on the townsite.[46] The town also had a night watchman and later, a full-time patrolman.[34][42] There was never any crime or trouble in Elcor.[31][42] Always noted as a quiet, orderly town, Elcor managed to avoid the social vagaries of adjacent communities like Gilbert’s red-light district.[50][51][52]

One of the framehouses was used for the first school in Elcor.[53] It was not long before a new school was constructed. Elcor was included in the middle part of the Gilbert School system, known then as Independent School District No. 18. There were five school houses in the district. The McKinley-Elba school was built in 1900 halfway between McKinley and the Elba location, complete with its own well and windmill.[14][54] It had four teachers and housed classes through the 8th grade, accommodating pupils of both communities.[14][53][34] Students walked to school over boardwalks.[14] There were also three primary schools in the district, one of which remained at the Elba location on Malta Street.[54][55]

Before you could rent a home in Elcor, you had to promise to take in boarders.[16][34] The company rented a "cottage" for $7.50 per month, which later included electricity.[34] Homes were charged an additional $1.00 per month when water was piped in from Gilbert.[16] Although people were later allowed to own their own homes (even though the land on which the houses stood belonged to the mining company),[56][34] the rent did not go up once until the homes were moved from Elcor in 1955.[34]

All families had their own gardens from which they got many of their vegetables which lasted through the long winter months.[34] Some families raised cows, pigs and chickens; others had horses for carrying firewood.[34] There was little refrigeration in those days, and perishables were difficult to keep.[57] Before the mercantile came to Elcor, residents went to the J.P. Ahlin store in McKinley, or the Saari, Campbell and Kraker Mercantile in Gilbert.[34][58] Deliveries were made daily, and at the same time of delivery, orders were taken for the following day. Every home would charge and pay once a month on pay days.[34]

The Finnish Hall became the Elcor Mercantile along with an official U.S. Post Office in 1920.[2][14][56][16][59] The convenience of having a local store and post office were greatly appreciated by the town.[56] When the post office began operation, much confusion resulted in the mail because there was another town in southeastern Minnesota just east of Rochester named “Elba”.[49][14][56][16][31] The name “Corsica” was attempted with the same result.[56] Finally, the name of the community was coined from half of each of the two mines around which the location was centered, and “Elcor” was the result.[49][14][56][16] The name “Elcor” was emblazoned in large white letters on the town water tower.[56]

Mail for the community was picked up twice daily at the railroad station for the Duluth and Iron Range Railroad (later the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railroad) erroneously spelled "Elcore" south of the store at 10:00 AM and about 12:00 noon.[60][61][62] Later, the Elcor Mercantile diversified into the up-and-coming petroleum business, selling Conoco gasoline, kerosene, fuel oils, motor oils, and grease, even outboard motors.[4][57] Sidewalks of cement were built to line the shady streets, and fire hydrants, painted bright red, were installed.[56] Homes were insulated, and people began to purchase refrigerators for their kitchens.[57] Manilla Street and Maritana Avenue were paved. Greyhound Bus Lines established a stop at the Elcor Mercantile.[57] A baseball team was entered in the old East Mesaba League,[48] and the Elcor Mercantile sponsored an ice-hockey team which was one of the best on the Iron Range, the “Elcor-Conoco’s”.[57] Chicago Blackhawks ice-hockey goaltender Sam LoPresti was born in Elcor.[63]

The Corsica and Elba mines remained the chief source of employment until 1926, when the first sign of Elcor’s fate came: the underground Elba mine closed.[2][14][15][42] It had been mined out. A few years later, the Corsica mine was converted into an open pit and the future of the town once again seemed secure.[2][56] Then the Great Depression hit. In the fall of 1929, Corsica closed and stayed closed for many years, with only a few salaried people retained.[57] The Corsica mine remained idle until 1940, ironically receiving an honorable mention in the National Safety Competition from the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1934.[65] Once World War II began, the mining business boomed again.[2][14][66]

Abandonment

In 1954, the Corsica pit was shut down. Workers were told that the shutdown was “temporary” because the demand for that particular type of ore had declined.[15][42] The pit was allowed to flood, and Pickands Mather officially conceded that “temporary” may stretch into quite a long time, although “eventually” the mine would perhaps be reopened.[11][12][15][42] Mining operations ceased.[14] A year later, Pickands Mather and Company, manager of the mines at Elcor and the land on which the houses rested, exercised its authority and ordered residents to vacate the property.[66] By edict of the mining company, the remaining families were forced out of the townsite so it could reclaim the land.[2][11][12][14][66][42]

People differ on why the order was issued. Some recall the company wanting the land as a dump site. Others contended that the company no longer wanted to tend to the town’s maintenance.[16] Still others thought the company decided it was not economical to own houses anymore.[67] No one in authority either knew or would reveal what was to become of the land in the future.[2][42]

Residents renting the company-owned houses were given the option to buy them at bargain prices provided they move them out of town.[68][69] For many, it took a great chunk out of their life savings to relocate elsewhere, taking along the homes in which they lived and leaving behind only empty foundations and uprooted lots in caravans of homes that moved along the highway.[42] Most Elcor residents purchased lots in the surrounding communities trying to beat land speculators. In the few months when it became official that Elcor’s fate was sealed, land prices skyrocketed. Lots that had originally been $75.00 were now being sold for as much as $500.00.[42] Most of the remaining families moved a mile west to Gilbert, although other homes were replanted in nearby McKinley.[16] The last vestiges of the staid old mining community were removed in 1956.[49][14][15] Every single building was torn down or removed.[69] All that remained for some years after were old foundations, sidewalks, rusting stoves, pipes, bottles and yard shrubbery, formerly visible from the old section of Minnesota State Highway 135 between Gilbert and Biwabik, now also a thing of the past. A rusted fire hydrant adorned what was once a street corner, and a porcelain toilet bowl remained bolted to a concrete floor.[11][12][14] An abandoned rail line for the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railway went through what was left of the townsite. Mine shafts were boarded up with old timbers.[70] After everyone had left, the company dumped heaps of iron ore on the roads leading into Elcor, and in the process a ghost town was made out of a thriving community.[2][11][12][15][16]

The only landmark that remained for a time at the old mining location was a 200-foot smokestack, which stood as a lone sentry near the Corsica mine since operations there had ceased.[71][72] The construction and design of the vintage stack was unique, built by Cornish men of the mining industry in 1901.[43][71] The last of its kind on the Mesabi Iron Range, the Iron Range Historical Society wanted the stack saved and wished to preserve it as a potential off-premises attraction, since it was structurally sound and historically significant.[43][71][72] However, demolition of the stack had already been contracted as a part of the Minnesota Mineland Reclamation Act Abandoned Minelands Cleanup Program.[73][74][75][76] Many people feared it might fall and injure someone; others considered it an aerial obstruction.[43][71] In 1976, the stack was destroyed, but it took three blasting attempts and nearly 100 pounds of dynamite to bring the stubborn structure down.[43][71][72] After the demolition of the Corsica mine stack, responsibility for the land on which Elcor stood changed hands on several different occasions. As early as 1978, management for the property was acquired by the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company. Property rights were then transferred to LTV Steel after the merger of Jones and Laughlin with Republic Steel in 1984. Property rights were later acquired by the Inland Steel Company in a transfer from LTV. In 1993, Inland Steel began stripping the overburden near the old townsite, and the Laurentian mine was born.[2][70] The mine is now owned by ArcelorMittal and has since been renamed the Minorca mine after the acquisition of Inland Steel by Mittal in 1998.[77] The Minorca mine is now centered over Elcor’s former location.

See also

References

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Archived from the original on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Elcor: A gentle, good neighborhood now more than 50 years gone". Mesabi Daily News (MN). 18 Mar 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ "USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Elcor-People and the Place". Gilbert Herald (MN). 14 Apr 1982.

- ↑ Davis 1964, p. 31.

- 1 2 Havinghurst 1958, p. 47.

- ↑ Pederson, C.A. (March–April 1958). "Southern Minnesota's Iron Mines". The Minnesota Volunteer. © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2014. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046: 48–50. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Davis 1964, p. 34.

- ↑ "Laurentian Mixed Forest Province". © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2014. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ "Minnesota Climate Extremes". © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2014. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Breining, Greg (July–August 1992). "Mesabi Ghosts". The Minnesota Volunteer. © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2014. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046: 44–53. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Breining, Greg (March 1982). "Ghost Towns on the Range". Minnesota Monthly: 17–19.

- 1 2 3 Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "Iron Range History: Elcor (Elba-Corsica) Memories". Mesabi Daily News (MN). 14 Oct 1976.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lamppa 1962, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Holten, Jon (5 Jul 1982). "Elcor, City of Memories, Comes Alive Once Again". Minneapolis Star and Tribune (MN).

- ↑ Alanen, Arnold (Fall 1982). "The 'Locations', Company Communities on Minnesota's Iron Ranges" (PDF). Minnesota History. © Minnesota Historical Society: 94–107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ↑ "Sparta". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Sparta, MN". Mesabi Trail. St. Louis & Lake Counties Regional Railroad Authority. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ "Sparta MN - Birthplace of Eveleth Hockey?". Vintage Minnesota Hockey. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Swensson, Andrea (28 February 2013). "Rich Mattson's Sparta Sound is part of a new era of music on the Iron Range". The Current. Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Walsh, Jim (21 November 2014). "Singing an ode to Sparta, the Iron Range's vanishing town". MinnPost. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Gerth, Austin (26 November 2014). "This town is becoming like a ghost town: Rich Mattson releases a song about his disappearing Iron Range home". The Current. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "Pineville". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Belgrade". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Genoa". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Van Brunt 1921, pp. 455-456.

- ↑ Bordeau, Sanford P.; Krause, James L.; Krause, Kathie I. (2002). "An Early History of Weimer, Sparta, Genoa and Gilbert, Minnesota". Angelfire. Gary L. Gorsha. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ "Genoa OHV Trail" (PDF). Iron Range Tourism. © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2008. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Reynolds & Dawson 2011, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Fleichtinger, Gail (6 Jul 1982). "Vanished Town of Elcor Still Exists in Ex-Residents' Memories". Duluth News Tribune (MN).

- 1 2 3 "Historic Scene at the Village of Elcor, Mesabi Iron Range". Skillings' Mining Review: 27. 19 November 1960.

- ↑ Wikipedia Contributors (23 June 2017). "Lake Huron". Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Phillipich, John, Jr.; Phillipich (Torresani), Edith (January 7, 1974). "Bits and Pieces" (Interview). Interview with Iron Range Historical Society. Gilbert, Minnesota.

- ↑ Lamppa 1962, p. 101.

- 1 2 3 Woodbridge & Pardee 1910, p. 737.

- 1 2 Van Brunt 1921, p. 469.

- 1 2 "William Philip Chinn, General Manager, Pickands Mather & Company: A Biography". The Explosives Engineer. January 1930.

- ↑ Appleby 1920, pp. 149, 151.

- ↑ Lamppa 1962, p. 102.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Eldot, Walter (17 Jul 1955). "Death of a Mining Town". Duluth News Tribune (MN).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Before...and After". Gilbert Herald (MN). 29 Sep 1976.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 25.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Lamppa 1962, p. 104.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 15.

- 1 2 Lamppa 1962, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 5.

- ↑ "Citizens group denounces town's 'Whorehouse Days'". USA Today. 27 Jan 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Tyssen, Linda (26 Jan 2005). "Gilbert citizens give event the red light". Mesabi Daily News (MN). Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ↑ "Minnesota Group Denounces 'Whorehouse Days'". Sodomy Laws. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- 1 2 Lamppa 1962, p. 103.

- 1 2 Van Brunt 1921, p. 462.

- ↑ Sedgeman, William. "Elcor as remembered by Mr. William Sedgeman" (Interview). Interview with Denise Dombrowski. Gilbert, Minnesota: Iron Range Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lamppa 1962, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 16.

- ↑ Gilbert Centennial 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ "St. Louis County". Jim Forte Postal History. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Upham 2001, p. 520.

- ↑ Leighton 1998, p. 10.

- ↑ "Elcore Station (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame-Sam L. LoPresti Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "St. Louis County Aerial Photography". © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2013. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Adams, William W. (July 1935). "1934 National Safety Competition". The Explosives Engineer. 13-14: 219. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Lamppa 1962, p. 107.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 24.

- ↑ Phillipich et al. 1982, p. 8.

- 1 2 Lamppa 1962, p. 108.

- 1 2 Glavan, Gregory (September 1999). "Elcor, An Iron Range Ghost Town: The Elcor Smokestack". Range Reminiscing. 24: 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leschak, Pam (28 Sep 1976). "There She Blows-Finally! Attempt to Save it Too Late: Old Stack Blasted Down". Hibbing Daily Tribune (MN).

- 1 2 3 Radomski, Robyn (28 Sep 1976). "Last Stack Bombed: Old Stack Blown; Protests Overridden". Mesabi Daily News (MN).

- ↑ "Minnesota Mineland Reclamation Act" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ↑ Leschak, Pam (September–October 1977). "Big Clean-Up on the Iron Range". The Minnesota Volunteer. © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2013. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046: 37–41. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ "Mineland Reclamation". © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2014. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Mineland Reclamation". Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "USA Operations". ArcelorMittal. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

Sources

- Appleby, William (1920). Mining Directory of Minnesota for 1920. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. OCLC 1465786. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- Davis, Edward Wilson (1964). Pioneering with Taconite. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0873514965. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Gilbert Centennial. Gilbert, MN: Iron Range Historical Society. 2008.

- Havinghurst, Walter (1958). Vein of Iron: The Pickands-Mather Story. Cleveland and New York: World Publishing Company. ASIN B0007DMASO. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Lamppa, Marvin (1962). Ghost Towns and Locations of the Vermilion and East Mesabi Mining Districts (Thesis). University of Minnesota. OCLC 19474669.

- Leighton, Hudson (1998). Gazetteer of Minnesota Railroad Towns, 1861-1997. Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books. ISBN 0-915709-61-9. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Phillipich, Leonard; et al. (1982). Elba-Elcor Reunion 1897-1956 'A Collection of Memories'. Gilbert, MN: Elcor Reunion Committee.

- Reynolds, Terry S.; Dawson, Virginia P. (2011). Iron Will: Cleveland-Cliffs and the Mining of Iron Ore, 1847-2006. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3511-6. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Upham, Warren (2001). Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia (Third ed.). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-396-7. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Van Brunt, Walter (1921). History of Duluth and St. Louis County; Their Story and People. 1. Chicago and New York: American Historical Society. ISBN 9781278952086. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Woodbridge, Dwight Edwards; Pardee, John Stone (1910). History of Duluth and St. Louis County, Past and Present. 1. Chicago: C.F. Cooper & Company. ISBN 1235829103. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

Further reading

- Lamppa, Marvin G (2004). Minnesota's Iron Country: Rich Ore, Rich Lives. Duluth, MN: Lake Superior Port Cities. ISBN 978-0942235562.

External links

- Iron Range Historical Society Website

- "This Town (Ghost Town)" (2014), folk song about the disappearing Iron Range town of Sparta, Minnesota at YouTube