Peru

Coordinates: 10°S 76°W / 10°S 76°W

| Republic of Peru | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: "Firme y feliz por la unión" (Spanish) "Firm and Happy for the Union" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Lima 12°2.6′S 77°1.7′W / 12.0433°S 77.0283°W |

| Official languagesa | |

| Ethnic groups (2013[1]) |

|

| Demonym | Peruvian |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Pedro Pablo Kuczynski | |

| Fernando Zavala Lombardi | |

| Martín Vizcarra | |

| Mercedes Aráoz | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Independence from the Kingdom of Spain | |

• Declared | 28 July 1821 |

| 9 December 1824 | |

• Recognized | 14 August 1879 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,285,216 km2 (496,225 sq mi) (19th) |

• Water (%) | 0.41 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 31,826,018 (43th) |

• 2007 census | 28,220,764 |

• Density | 23/km2 (59.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $429.711 billion[2] (46th) |

• Per capita | $13,501[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $207.072 billion[2] (49th) |

• Per capita | $6,506[2] |

| Gini (2014) |

medium |

| HDI (2015) |

high · 87th |

| Currency | Sol (PEN) |

| Time zone | PET (UTC−5) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +51 |

| ISO 3166 code | PE |

| Internet TLD | .pe |

| |

Peru (/pəˈruː/; Spanish: Perú [peˈɾu]; Quechua: Piruw [pʰɪɾʊw];[5] Aymara: Piruw [pɪɾʊw]), officially the Republic of Peru (Spanish: ![]() República del Perú ), is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the west by the Pacific Ocean. Peru is an extremely biodiverse country with habitats ranging from the arid plains of the Pacific coastal region in the west to the peaks of the Andes mountains vertically extending from the north to the southeast of the country to the tropical Amazon Basin rainforest in the east with the Amazon river.[6]

República del Perú ), is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the west by the Pacific Ocean. Peru is an extremely biodiverse country with habitats ranging from the arid plains of the Pacific coastal region in the west to the peaks of the Andes mountains vertically extending from the north to the southeast of the country to the tropical Amazon Basin rainforest in the east with the Amazon river.[6]

Peruvian territory was home to ancient cultures spanning from the Norte Chico civilization in Caral (one of the oldest in the world with settlements as old as 3200 BC) to the Inca Empire, the largest state in Pre-Columbian America. The Spanish Empire conquered the region in the 16th century and established a Viceroyalty with its capital in Lima, which included most of its South American colonies. Ideas of political autonomy later spread throughout Spanish America and Peru gained its independence, which was formally proclaimed in 1821 after the occupation by military campaigns of José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar and only after the battle of Ayacucho, three years after proclamation, Peru ensured its independence. After achieving independence, the country remained in recession and kept a low military profile until an economic rise based on the extraction of raw and maritime materials struck the country, which ended shortly before the war of the Pacific. Subsequently, the country has undergone changes in government from oligarchic to democratic systems. Peru has gone through periods of political unrest and internal conflict as well as periods of stability and economic upswing.

Peru is a representative democratic republic divided into 25 regions. It is a developing country with a high Human Development Index score and a poverty level around 25.8 percent.[7] Its main economic activities include mining, manufacturing, agriculture and fishing.

The Peruvian population, estimated at 31.2 million in 2015,[8] is multiethnic, including Amerindians, Europeans, Africans and Asians. The main spoken language is Spanish, although a significant number of Peruvians speak Quechua or other native languages. This mixture of cultural traditions has resulted in a wide diversity of expressions in fields such as art, cuisine, literature, and music.

Etymology

The name of the country may be derived from Birú, the name of a local ruler who lived near the Bay of San Miguel, Panama, in the early 16th century.[9] When his possessions were visited by Spanish explorers in 1522, they were the southernmost part of the New World yet known to Europeans.[10] Thus, when Francisco Pizarro explored the regions farther south, they came to be designated Birú or Perú.[11]

An alternative history is provided by the contemporary writer Inca Garcilasco de la Vega, son of an Inca princess and a conquistador. He said the name Birú was that of a common Indian happened upon by the crew of a ship on an exploratory mission for governor Pedro Arias de Ávila, and went on to relate more instances of misunderstandings due to the lack of a common language.[12]

The Spanish Crown gave the name legal status with the 1529 Capitulación de Toledo, which designated the newly encountered Inca Empire as the province of Peru.[13] Under Spanish rule, the country adopted the denomination Viceroyalty of Peru, which became Republic of Peru after independence.

History

Prehistory and pre-Columbian period

The earliest evidences of human presence in Peruvian territory have been dated to approximately 9,000 BC.[14] Andean societies were based on agriculture, using techniques such as irrigation and terracing; camelid husbandry and fishing were also important. Organization relied on reciprocity and redistribution because these societies had no notion of market or money.[15] The oldest known complex society in Peru, the Norte Chico civilization, flourished along the coast of the Pacific Ocean between 3,000 and 1,800 BC.[16] These early developments were followed by archaeological cultures that developed mostly around the coastal and Andean regions throughout Peru. The Cupisnique culture which flourished from around 1000 to 200 BC[17] along what is now Peru's Pacific Coast was an example of early pre-Incan culture. The Chavín culture that developed from 1500 to 300 BC was probably more of a religious than a political phenomenon, with their religious centre in Chavin de Huantar.[18] After the decline of the Chavin culture around the beginning of the Christian millennium, a series of localized and specialized cultures rose and fell, both on the coast and in the highlands, during the next thousand years. On the coast, these included the civilizations of the Paracas, Nazca, Wari, and the more outstanding Chimu and Mochica. The Mochica, who reached their apogee in the first millennium AD, were renowned for their irrigation system which fertilized their arid terrain, their sophisticated ceramic pottery, their lofty buildings, and clever metalwork. The Chimu were the great city builders of pre-Inca civilization; as loose confederation of cities scattered along the coast of northern Peru and southern Ecuador, the Chimu flourished from about 1150 to 1450. Their capital was at Chan Chan outside of modern-day Trujillo. In the highlands, both the Tiahuanaco culture, near Lake Titicaca in both Peru and Bolivia, and the Wari culture, near the present-day city of Ayacucho, developed large urban settlements and wide-ranging state systems between 500 and 1000 AD.[19]

In the 15th century, the Incas emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, formed the largest empire in pre-Columbian America with their capital in Cusco.[20] The Incas of Cusco originally represented one of the small and relatively minor ethnic groups, the Quechuas. Gradually, as early as the thirteenth century, they began to expand and incorporate their neighbors. Inca expansion was slow until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when the pace of conquest began to accelerate, particularly under the rule of the great emperor Pachacuti. Under his rule and that of his son, Topa Inca Yupanqui, the Incas came to control most of the Andean region, with a population of 9 to 16 million inhabitants under their rule. Pachacuti also promulgated a comprehensive code of laws to govern his far-flung empire, while consolidating his absolute temporal and spiritual authority as the God of the Sun who ruled from a magnificently rebuilt Cusco.[21] From 1438 to 1533, the Incas used a variety of methods, from conquest to peaceful assimilation, to incorporate a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean mountain ranges, from southern Colombia to Chile, between the Pacific Ocean in the west and the Amazon rainforest in the east. The official language of the empire was Quechua, although hundreds of local languages and dialects were spoken. The Inca referred to their empire as Tawantinsuyu which can be translated as "The Four Regions" or "The Four United Provinces." Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the worship of Inti, the sun god and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama.[22] The Incas considered their King, the Sapa Inca, to be the "child of the sun."[23]

Conquest and colonial period

Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca became emperor when he defeated and executed his older half-brother Huascar in a civil war sparked by the death of their father, Inca Huayna Capac. In December 1532, a party of conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro defeated and captured the Inca Emperor Atahualpa in the Battle of Cajamarca. The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military conflicts, it was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting but ended in Spanish victory and colonization of the region known as the Viceroyalty of Peru with its capital at Lima, which became known as "The City of Kings". The conquest of the Inca Empire led to spin-off campaigns throughout the viceroyalty as well as expeditions towards the Amazon Basin as in the case of Spanish efforts to quell Amerindian resistance. The last Inca resistance was suppressed when the Spaniards annihilated the Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba in 1572.

The indigenous population dramatically collapsed principally due to epidemic diseases introduced by the Spanish.[24] Exploitation and socioeconomic change also contributed to the collapse. Viceroy Francisco de Toledo reorganized the country in the 1570s with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and Amerindian forced labor as its primary workforce.[25] With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at Potosí (present-day Bolivia) and Huancavelica, the viceroyalty flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. Peruvian bullion provided revenue for the Spanish Crown and fueled a complex trade network that extended as far as Europe and the Philippines.[26] Because of lack of available work force, African slaves were added to the labor population. The expansion of a colonial administrative apparatus and bureaucracy paralleled the economic reorganization. With the conquest started the spread of Christianity in South America; most people were forcefully converted to Catholicism, taking only a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Inca temples with churches, such as the Coricancha in the city of Cusco. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Catholics did not stray to other religions or beliefs. Peruvian Catholicism follows the syncretism found in many Latin American countries, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Christian celebrations.[27] In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Spanish settlers.

By the 18th century, declining silver production and economic diversification greatly diminished royal income.[28] In response, the Crown enacted the Bourbon Reforms, a series of edicts that increased taxes and partitioned the Viceroyalty.[29] The new laws provoked Túpac Amaru II's rebellion and other revolts, all of which were suppressed.[30] As a result of these and other changes, the Spaniards and their creole successors came to monopolize control over the land, seizing many of the best lands abandoned by the massive native depopulation. However, the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. The Treaty of Tordesillas was rendered meaningless between 1580 and 1640 while Spain controlled Portugal. The need to ease communication and trade with Spain led to the split of the viceroyalty and the creation of new viceroyalties of New Granada and Rio de la Plata at the expense of the territories that formed the viceroyalty of Peru; this reduced the power, prominence and importance of Lima as the viceroyal capital and shifted the lucrative Andean trade to Buenos Aires and Bogotá, while the fall of the mining and textile production accelerated the progressive decay of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Eventually, the viceroyalty would dissolve, as with much of the Spanish empire, when challenged by national independence movements at the beginning of the nineteenth century. These movements led to the formation of the majority of modern-day countries of South America in the territories that at one point or another had constituted the Viceroyalty of Peru.[31] The conquest and colony brought a mix of cultures and ethnicities that did not exist before the Spanish conquered the Peruvian territory. Even though many of the Inca traditions were lost or diluted, new customs, traditions and knowledge were added, creating a rich mixed Peruvian culture.[27]

Independence

In the early 19th century, while most of South America was swept by wars of independence, Peru remained a royalist stronghold. As the elite vacillated between emancipation and loyalty to the Spanish Monarchy, independence was achieved only after the occupation by military campaigns of José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar.

The economic crises, the loss of power of Spain in Europe, the war of independence in North America and native uprisings all contributed to a favorable climate to the development of emancipating ideas among the criollo population in South America. However, the criollo oligarchy in Peru enjoyed privileges and remained loyal to the Spanish Crown. The liberation movement started in Argentina where autonomous juntas were created as a result of the loss of authority of the Spanish government over its colonies.

After fighting for the independence of the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, José de San Martín created the Army of the Andes and crossed the Andes in 21 days, a great accomplishment in military history. Once in Chile he joined forces with Chilean army General Bernardo O’Higgins and liberated the country in the battles of Chacabuco and Maipú in 1818. On 7 September 1820, a fleet of eight warships arrived in the port of Paracas under the command of general Jose de San Martin and Thomas Cochrane, who was serving in the Chilean Navy. Immediately on 26 October they took control of the town of Pisco. San Martin settled in Huacho on 12 November, where he established his headquarters while Cochrane sailed north blockading the port of Callao in Lima. At the same time in the north, Guayaquil was occupied by rebel forces under the command of Gregorio Escobedo. Because Peru was the stronghold of the Spanish government in South America, San Martin’s strategy to liberate Peru was to use diplomacy. He sent representatives to Lima urging the Viceroy that Peru be granted independence, however all negotiations proved unsuccessful.

The Viceroy of Peru, Joaquin de la Pazuela named Jose de la Serna commander-in-chief of the loyalist army to protect Lima from the threatened invasion of San Martin. On 29 January, de la Serna organized a coup against de la Pazuela which was recognized by Spain and he was named Viceroy of Peru. This internal power struggle contributed to the success of the liberating army. In order to avoid a military confrontation San Martin met the newly appointed viceroy, Jose de la Serna, and proposed to create a constitutional monarchy, a proposal that was turned down. De la Serna abandoned the city and on 12 July 1821 San Martin occupied Lima and declared Peruvian independence on 28 July 1821. He created the first Peruvian flag. Alto Peru (Bolivia) remained as a Spanish stronghold until the army of Simón Bolívar liberated it three years later. Jose de San Martin was declared Protector of Peru. Peruvian national identity was forged during this period, as Bolivarian projects for a Latin American Confederation floundered and a union with Bolivia proved ephemeral.[32]

Simon Bolivar launched his campaign from the north liberating the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the Battles of Carabobo in 1821 and Pichincha a year later. In July 1822 Bolivar and San Martin gathered in the Guayaquil Conference. Bolivar was left in charge of fully liberating Peru while San Martin retired from politics after the first parliament was assembled. The newly founded Peruvian Congress named Bolivar dictator of Peru giving him the power to organize the military.

With the help of Antonio José de Sucre they defeated the larger Spanish army in the Battle of Junín on 6 August 1824 and the decisive Battle of Ayacucho on 9 December of the same year, consolidating the independence of Peru and Alto Peru. Alto Peru was later established as Bolivia. During the early years of the Republic, endemic struggles for power between military leaders caused political instability.[33]

19th century to present

From the 1840s to the 1860s, Peru enjoyed a period of stability under the presidency of Ramón Castilla, through increased state revenues from guano exports.[34] However, by the 1870s, these resources had been depleted, the country was heavily indebted, and political in-fighting was again on the rise.[35] Peru embarked on a railroad-building program that helped but also bankrupted the country. In 1879, Peru entered the War of the Pacific which lasted until 1884. Bolivia invoked its alliance with Peru against Chile. The Peruvian Government tried to mediate the dispute by sending a diplomatic team to negotiate with the Chilean government, but the committee concluded that war was inevitable. Chile declared war on 5 April 1879. Almost five years of war ended with the loss of the department of Tarapacá and the provinces of Tacna and Arica, in the Atacama region. Two outstanding military leaders throughout the war were Francisco Bolognesi and Miguel Grau. Originally Chile committed to a referendum for the cities of Arica and Tacna to be held years later, in order to self determine their national affiliation. However, Chile refused to apply the Treaty, and neither of the countries could determine the statutory framework. After the War of the Pacific, an extraordinary effort of rebuilding began. The government started to initiate a number of social and economic reforms in order to recover from the damage of the war. Political stability was achieved only in the early 1900s.

Internal struggles after the war were followed by a period of stability under the Civilista Party, which lasted until the onset of the authoritarian regime of Augusto B. Leguía. The Great Depression caused the downfall of Leguía, renewed political turmoil, and the emergence of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA).[36] The rivalry between this organization and a coalition of the elite and the military defined Peruvian politics for the following three decades. A final peace treaty in 1929, signed between Peru and Chile called the Treaty of Lima, returned Tacna to Peru. Between 1932 and 1933, Peru was engulfed in a year-long war with Colombia over a territorial dispute involving the Amazonas department and its capital Leticia. Later, in 1941, Peru became involved in the Ecuadorian-Peruvian War, after which the Rio Protocol sought to formalize the boundary between those two countries. In a military coup on 29 October 1948, Gen. Manuel A. Odria became president. Odría's presidency was known as the Ochenio. Momentarily pleasing the oligarchy and all others on the right, but followed a populist course that won him great favor with the poor and lower classes. A thriving economy allowed him to indulge in expensive but crowd-pleasing social policies. At the same time, however, civil rights were severely restricted and corruption was rampant throughout his régime. Odría was succeeded by Manuel Prado Ugarteche. However, widespread allegations of fraud prompted the Peruvian military to depose Prado and install a military junta, led by Ricardo Pérez Godoy. Godoy ran a short transitional government and held new elections in 1963, which were won by Fernando Belaúnde Terry who assumed presidency until 1968. Belaúnde was recognized for his commitment to the democratic process. In 1968, the Armed Forces, led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado, staged a coup against Belaúnde. Alvarado's regime undertook radical reforms aimed at fostering development, but failed to gain widespread support. In 1975, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez forcefully replaced Velasco, paralyzed reforms, and oversaw the reestablishment of democracy.

Peru engaged in a brief successful conflict with Ecuador in the Paquisha War as a result of territorial dispute between the two countries. After the country experienced chronic inflation, the Peruvian currency, the sol, was replaced by the Inti in mid-1985, which itself was replaced by the nuevo sol in July 1991, at which time the new sol had a cumulative value of one billion old soles. The per capita annual income of Peruvians fell to $720 (below the level of 1960) and Peru's GDP dropped 20% at which national reserves were a negative $900 million. The economic turbulence of the time acerbated social tensions in Peru and partly contributed to the rise of violent rebel rural insurgent movements, like Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and MRTA, which caused great havoc throughout the country. Concerned about the economy, the increasing terrorist threat from Sendero Luminoso and MRTA, and allegations of official corruption, Alberto Fujimori assumed presidency in 1990. Fujimori implemented drastic measures that caused inflation to drop from 7,650% in 1990 to 139% in 1991. Faced with opposition to his reform efforts, Fujimori dissolved Congress in the auto-golpe ("self-coup") of 5 April 1992. He then revised the constitution; called new congressional elections; and implemented substantial economic reform, including privatization of numerous state-owned companies, creation of an investment-friendly climate, and sound management of the economy. Fujimori's administration was dogged by insurgent groups, most notably the Sendero Luminoso, who carried out terrorist campaigns across the country throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Fujimori cracked down on the insurgents and was successful in largely quelling them by the late 1990s, but the fight was marred by atrocities committed by both the Peruvian security forces and the insurgents: the Barrios Altos massacre and La Cantuta massacre by Government paramilitary groups, and the bombings of Tarata and Frecuencia Latina by Sendero Luminoso. Those incidents subsequently came to symbolize the human rights violations committed in the last years of violence.

During early 1995, once again Peru and Ecuador clashed in the Cenepa War, but in 1998 the governments of both nations signed a peace treaty that clearly demarcated the international boundary between them. In November 2000, Fujimori resigned from office and went into a self-imposed exile, avoiding prosecution for human rights violations and corruption charges by the new Peruvian authorities. Since the end of the Fujimori regime, Peru has tried to fight corruption while sustaining economic growth.[37] In spite of human rights progress since the time of insurgency, many problems are still visible and show the continued marginalization of those who suffered through the violence of the Peruvian conflict.[38]

A caretaker government presided over by Valentín Paniagua took on the responsibility of conducting new presidential and congressional elections. Afterwards Alejandro Toledo became president in 2001 to 2006.

On 28 July 2006 former president Alan García became President of Peru after winning the 2006 elections. In May 2008, Peru became a member of the Union of South American Nations.

On 5 June 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected President.

Government and politics

Government

Peru is a presidential representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. Under the current constitution, the President is the head of state and government; he or she is elected for five years and cannot serve consecutive terms.[39] The President designates the Prime Minister and, with his or her advice, the rest of the Council of Ministers.[40] Congress is unicameral with 130 members elected for five-year terms.[41] Bills may be proposed by either the executive or the legislative branch; they become law after being passed by Congress and promulgated by the President.[42] The judiciary is nominally independent,[43] though political intervention into judicial matters has been common throughout history and arguably continues today.[44]

The Peruvian government is directly elected, and voting is compulsory for all citizens aged 18 to 70.[45] Congress is currently composed of Fuerza Popular (72 seats), Peruanos Por el Kambio (17 seats), Frente Amplio (20 seats), Alianza para el Progreso (9 seats), Acción Popular (5 seats) and APRA (5 seats).[46]

Foreign relations

Peruvian foreign relations have historically been dominated by border conflicts with neighboring countries, most of which were settled during the 20th century.[47] Recently, Peru disputed its maritime limits with Chile in the Pacific Ocean.[48] Peru is an active member of several regional blocs and one of the founders of the Andean Community of Nations. It is also a participant in international organizations such as the Organization of American States and the United Nations. Javier Pérez de Cuéllar served as UN Secretary General from 1981 to 1991. Former President Fujimori’s tainted re-election to a third term in June 2000 strained Peru's relations with the United States and with many Latin American and European countries, but relations improved with the installation of an interim government in November 2000 and the inauguration of Alejandro Toledo in July 2001 after free and fair elections.

Peru is planning full integration into the Andean Free Trade Area. In addition, Peru is a standing member of APEC and the World Trade Organization, and is an active participant in negotiations toward a Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).

Military and law enforcement

The Peruvian Armed Forces are the military services of Peru, comprising independent Army, Navy and Air Force components. Their primary mission is to safeguard the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country. As a secondary mission they participate in economic and social development as well as in civil defense tasks.[49] Conscription was abolished in 1999 and replaced by voluntary military service.[50] The armed forces are subordinate to the Ministry of Defense and to the President as Commander-in-Chief.

The National Police of Peru is often classified as a part of the armed forces. Although in fact it has a different organization and a wholly civil mission, its training and activities over more than two decades as an anti-terrorist force have produced markedly military characteristics, giving it the appearance of a virtual fourth military service with significant land, sea and air capabilities and approximately 140,000 personnel. The Peruvian armed forces report through the Ministry of Defense, while the National Police of Peru reports through the Ministry of Interior.

Administrative divisions

Peru is divided into 25 regions and the province of Lima. Each region has an elected government composed of a president and council that serve four-year terms.[51] These governments plan regional development, execute public investment projects, promote economic activities, and manage public property.[52] The province of Lima is administered by a city council.[53] The goal of devolving power to regional and municipal governments was among others to improve popular participation. NGOs played an important role in the decentralization process and still influence local politics.[54]

Regions

Province

Metropolitan areas

Several metropolitan areas are defined for Peru - these overlap the district areas, and have limited authority. The largest of them, the Lima Metropolitan Area, is the seventh largest metropolis in the Americas.

Geography

Peru covers 1,285,216 km2 (496,225 sq mi) of western South America. It borders Ecuador and Colombia to the north, Brazil to the east, Bolivia to the southeast, Chile to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. The Andes mountains run parallel to the Pacific Ocean; they define the three regions traditionally used to describe the country geographically. The costa (coast), to the west, is a narrow plain, largely arid except for valleys created by seasonal rivers. The sierra (highlands) is the region of the Andes; it includes the Altiplano plateau as well as the highest peak of the country, the 6,768 m (22,205 ft) Huascarán.[55] The third region is the selva (jungle), a wide expanse of flat terrain covered by the Amazon rainforest that extends east. Almost 60 percent of the country's area is located within this region.[56]

Most Peruvian rivers originate in the peaks of the Andes and drain into one of three basins. Those that drain toward the Pacific Ocean are steep and short, flowing only intermittently. Tributaries of the Amazon River have a much larger flow, and are longer and less steep once they exit the sierra. Rivers that drain into Lake Titicaca are generally short and have a large flow.[57] Peru's longest rivers are the Ucayali, the Marañón, the Putumayo, the Yavarí, the Huallaga, the Urubamba, the Mantaro, and the Amazon.[58]

The largest lake in Peru, Lake Titicaca between Peru and Bolivia high in the Andes, is also the largest of South America.[59] The largest reservoirs, all in the coastal region of Peru, are the Poechos, Tinajones, San Lorenzo, and El Fraile reservoirs.[60]

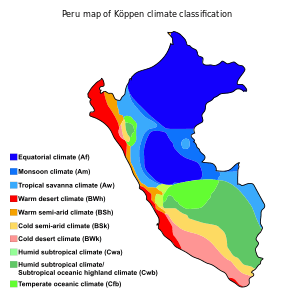

Climate

The combination of tropical latitude, mountain ranges, topography variations, and two ocean currents (Humboldt and El Niño) gives Peru a large diversity of climates. The coastal region has moderate temperatures, low precipitations, and high humidity, except for its warmer, wetter northern reaches.[61] In the mountain region, rain is frequent in summer, and temperature and humidity diminish with altitude up to the frozen peaks of the Andes.[62] The Peruvian Amazon is characterized by heavy rainfall and high temperatures, except for its southernmost part, which has cold winters and seasonal rainfall.[63]

Wildlife

Because of its varied geography and climate, Peru has a high biodiversity with 21,462 species of plants and animals reported as of 2003, 5,855 of them endemic.[64] Peru has over 1,800 species of birds (120 endemic), and 500 species of mammals and over 300 species of reptiles.[65] The hundreds of mammals include rare species like the puma, jaguar and spectacled bear. The Birds of Peru produce large amounts of guano, an economically important export. The Pacific holds large quantities of sea bass, flounder, anchovies, tuna, crustaceans, and shellfish, and is home to many sharks, sperm whales, and whales.[66]

Peru also has an equally diverse flora. The coastal deserts produce little more than cacti, apart from hilly fog oases and river valleys that contain unique plant life.[67] The Highlands above the tree-line known as puna is home to bushes, cactus, drought-resistant plants such as ichu, and the largest species of bromeliad - the spectacular Puya raimondii. The cloud-forest slopes of the Andes sustain moss, orchids, and bromeliads, and the Amazon rainforest is known for its variety of trees and canopy plants.[66]

Economy and infrastructure

The economy of Peru is classified as upper middle income by the World Bank[68] and is the 39th largest in the world.[69] Peru is, as of 2011, one of the world's fastest-growing economies owing to the economic boom experienced during the 2000s.[70] It has a high Human Development Index of .752 based on 2011 data. Historically, the country's economic performance has been tied to exports, which provide hard currency to finance imports and external debt payments.[71] Although they have provided substantial revenue, self-sustained growth and a more egalitarian distribution of income have proven elusive.[72] According to 2010 data, 31.3% of its total population is poor, including 9.8% that lives in extreme poverty.[73] Inflation in 2012 was the lowest in Latin America at only 1.8%, but increased in 2013 as oil and commodity prices rose; as of 2014 it stands at 2.5%.[74] The unemployment rate has fallen steadily in recent years, and as of 2012 stands at 3.6%.

Peruvian economic policy has varied widely over the past decades. The 1968–1975 government of Juan Velasco Alvarado introduced radical reforms, which included agrarian reform, the expropriation of foreign companies, the introduction of an economic planning system, and the creation of a large state-owned sector. These measures failed to achieve their objectives of income redistribution and the end of economic dependence on developed nations.[75]

Despite these results, most reforms were not reversed until the 1990s, when the liberalizing government of Alberto Fujimori ended price controls, protectionism, restrictions on foreign direct investment, and most state ownership of companies.[76] Reforms have permitted sustained economic growth since 1993, except for a slump after the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[77]

Services account for 53% of Peruvian gross domestic product, followed by manufacturing (22.3%), extractive industries (15%), and taxes (9.7%).[78] Recent economic growth has been fueled by macroeconomic stability, improved terms of trade, and rising investment and consumption.[79] Trade is expected to increase further after the implementation of a free trade agreement with the United States signed on 12 April 2006.[80] Peru's main exports are copper, gold, zinc, textiles, and fish meal; its major trade partners are the United States, China, Brazil, and Chile.[81]

Water supply and sanitation

The water and sanitation sector in Peru has made important advances in the last two decades, including the increase of water coverage from 30% to 85% between 1980 and 2010. Sanitation coverage has also increased from 9% to 37% from 1985 to 2010 in rural areas.[82] Advances have also been achieved concerning the disinfection of drinking water and in sewage treatment. Nevertheless, many challenges remain, such as:

- Insufficient service coverage;

- Poor service quality which puts the population’s health at risk;

- Deficient sustainability of built systems;

- Tariffs that do not cover the investment and operational costs, as well as the maintenance of services;

- Institutional and financial weakness; and,

- Excess of human resources, poorly qualified, and high staff turnover.

Demographics

Urbanization

| Largest cities or towns in Peru Estimated 2014 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Lima  Arequipa |

1 | Lima | Lima | 9.735.587 (Metro pop.) [83] | 11 | Juliaca | Puno | 267.174 |  Trujillo  Chiclayo |

| 2 | Arequipa | Arequipa | 989.919(Metro pop.) | 12 | Ica | Ica | 241.903 | ||

| 3 | Trujillo | La Libertad | 935.147(Metro pop.) | 13 | Cajamarca | Cajamarca | 218.775 | ||

| 4 | Chiclayo | Lambayeque | 801.580(Metro pop.) | 14 | Pucallpa | Ucayali | 211.631 | ||

| 5 | Huancayo | Junín | 501.384 | 15 | Sullana | Piura | 199.606 | ||

| 6 | Iquitos | Loreto | 432.476 | 16 | Ayacucho | Ayacucho | 177.420 | ||

| 7 | Piura | Piura | 430.319 | 17 | Chincha Alta | Ica | 174.575 | ||

| 8 | Cusco | Cusco | 420.137 | 18 | Huánuco | Huánuco | 172.924 | ||

| 9 | Chimbote | Ancash | 367.850 | 19 | Tarapoto | San Martín | 141.053 | ||

| 10 | Tacna | Tacna | 288.698 | 20 | Puno | Puno | 138.723 | ||

Ethnic groups

Peru is a multiethnic nation formed by the combination of different groups over five centuries. Amerindians inhabited Peruvian territory for several millennia before Spanish Conquest in the 16th century; according to historian Noble David Cook their population decreased from nearly 5–9 million in the 1520s to around 600,000 in 1620 mainly because of infectious diseases.[84] Spaniards and Africans arrived in large numbers under colonial rule, mixing widely with each other and with indigenous peoples. After independence, there has been gradual immigration from England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.[85] Chinese and Japanese arrived in the 1850s as a replacement for slave workers and have since become a major influence in Peruvian society.[86]

Population

With about 31.2 million inhabitants, Peru is the fifth most populous country in South America.[8] Its demographic growth rate declined from 2.6% to 1.6% between 1950 and 2000; population is expected to reach approximately 42 million in 2050.[87] As of 2007, 75.9% lived in urban areas and 24.1% in rural areas.[88] Major cities include the Lima Metropolitan Area (home to over 9.8 million people), Arequipa, Trujillo, Chiclayo, Piura, Iquitos, Cusco, Chimbote, and Huancayo; all reported more than 250,000 inhabitants in the 2007 census.[89] There are 15 uncontacted Amerindian tribes in Peru.[90]

Language

According to the Peruvian Constitution of 1993, Peru's official languages are Spanish and Quechua, Aymara and other indigenous languages in areas where they predominate. Spanish is spoken by 84.1% of the population and Quechua by 13%, Aymara by 1.7% while other languages make up the remaining 1.2%.[69]

Spanish is used by the government and is the mainstream language of the country, which is used by the media and in educational systems and commerce. Amerindians who live in the Andean highlands speak Quechua and Aymara and are ethnically distinct from the diverse indigenous groups who live on the eastern side of the Andes and in the tropical lowlands adjacent to the Amazon basin. Peru's distinct geographical regions are mirrored in a language divide between the coast where Spanish is more predominant over the Amerindian languages, and the more diverse traditional Andean cultures of the mountains and highlands. The indigenous populations east of the Andes speak various languages and dialects. Some of these groups still adhere to traditional indigenous languages, while others have been almost completely assimilated into the Spanish language. There has been an increasing and organized effort to teach Quechua in public schools in the areas where Quechua is spoken. In the Peruvian Amazon, numerous indigenous languages are spoken, including Asháninka, Bora, and Aguaruna.[91]

Religion

In the 2007 census, 81.3% of the population over 12 years old described themselves as Catholic, 12.5% as Evangelical Protestant, 3.3% as other Protestant, Judaism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and Jehovah's Witness, and 2.9% as non-religious.[92] Literacy was estimated at 92.9% in 2007; this rate is lower in rural areas (80.3%) than in urban areas (96.3%).[93] Primary and secondary education are compulsory and free in public schools.[69][94]

Amerindian religious traditions also play a major role in the beliefs of Peruvians. Catholic festivities like Corpus Christi, holy week and Christmas sometimes blend with Amerindian traditions. Amerindian festivities which were celebrated since pre-Columbian times are also widespread throughout the nation. Inti Raymi, which is an old Inca festival, is still celebrated.

The majority of towns, cities and villages have their own official church or cathedral and patron saint.

Toponyms

Many of the Peruvian toponyms have indigenous sources. In the Andes communities of Ancash, Cusco and Puno Quechua or Aymara names are overwhelmingly predominat. Their Spanish-based orthography, however, is in conflict with the normalized alphabets of these languages. According to Article 20 of Decreto Supremo No 004-2016-MC (Supreme Decree) which approves the Regulations to Law 29735, published in the official newspaper El Peruano on July 22, 2016, adequate spellings of the toponyms in the normalized alphabets of the indigenous languages must progressively be proposed with the aim of standardizing the namings used by the National Geographic Institute (Instituto Geográfico Nacional, IGN) The National Geographic Institute realizes the necessary changes in the official maps of Peru.[95]

Culture

Peruvian culture is primarily rooted in Amerindian and Spanish traditions,[96] though it has also been influenced by various Asian, African, and other European ethnic groups. Peruvian artistic traditions date back to the elaborate pottery, textiles, jewelry, and sculpture of Pre-Inca cultures. The Incas maintained these crafts and made architectural achievements including the construction of Machu Picchu. Baroque dominated colonial art, though modified by native traditions.[97]

During this period, most art focused on religious subjects; the numerous churches of the era and the paintings of the Cuzco School are representative.[98] Arts stagnated after independence until the emergence of Indigenismo in the early 20th century.[99] Since the 1950s, Peruvian art has been eclectic and shaped by both foreign and local art currents.[100]

Peruvian literature is rooted in the oral traditions of pre-Columbian civilizations. Spaniards introduced writing in the 16th century; colonial literary expression included chronicles and religious literature. After independence, Costumbrism and Romanticism became the most common literary genres, as exemplified in the works of Ricardo Palma.[101] The early 20th century's Indigenismo movement was led by such writers as Ciro Alegría[102] and José María Arguedas.[103] César Vallejo wrote modernist and often politically engaged verse. Modern Peruvian literature is recognized thanks to authors such as Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, a leading member of the Latin American Boom.[104]

Peruvian cuisine blends Amerindian and Spanish food with strong influences from Chinese, African, Arab, Italian, and Japanese cooking.[105] Common dishes include anticuchos, ceviche, and pachamanca. Peru's varied climate allows the growth of diverse plants and animals good for cooking.[106] Peru's diversity of ingredients and cooking techniques is receiving worldwide acclaim.[107]

Peruvian music has Andean, Spanish, and African roots.[108] In pre-Hispanic times, musical expressions varied widely in each region; the quena and the tinya were two common instruments.[109] Spaniards introduced new instruments, such as the guitar and the harp, which led to the development of crossbred instruments like the charango.[110] African contributions to Peruvian music include its rhythms and the cajón, a percussion instrument. Peruvian folk dances include marinera, tondero, zamacueca, diablada and huayno.[111]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Ethnic groups of Perú". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peru". International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ Quechua name used by government of Peru is Perú (see Quechua-language version of Peru Parliament website Archived 30 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. and Quechua-language version of Peru Constitution ), but common Quechua name is Piruw

- ↑ Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (ed.):Perú: País megaviverso Archived 22 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ UN: Peru Posts One of Region’s Best Reductions in Poverty in 2011 Archived 18 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Andean Air Mail and Peruvian Times, 28 November 2012.

- 1 2 "PERÚ: ESTIMACIONES Y PROYECCIONES DE LA POBLACION TOTAL POR AÑOS CALENDARIO Y EDADES SIMPLES, 1995-2025". Perú: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población Departamental, por Años Calendario y Edades Simples, 1995-2025. INEI. November 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. El nombre del Perú. Lima: Talleres Gráficos P.L. Villanueva, 1968, p. 83.

- ↑ Raúl Porras Barrenechea, El nombre del Perú, p. 84.

- ↑ Raúl Porras Barrenechea, El nombre del Perú, p. 86.

- ↑ Vega, Garcilasco, Commentarios Reales de los Incas, Editoriial Mantaro, Lima, ed. 1998. pp.14-15. First published in Lisbon in 1609.

- ↑ Raúl Porras Barrenechea, El nombre del Perú, p. 87.

- ↑ Dillehay, Tom, Duccio Bonavia and Peter Kaulicke (2004). "The first settlers". In Helaine Silverman (ed.), Andean archaeology. Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 0631234012, p. 20.

- ↑ Mayer, Enrique (2002). The articulated peasant: household economies in the Andes. Boulder: Westview, ISBN 081333716X, pp. 47–68

- ↑ Haas, Jonathan, Creamer, Winifred and Ruiz, Alvaro (2004). "Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru". Nature. 432: 1020–1023. PMID 15616561. doi:10.1038/nature03146.

- ↑ Cordy-Collins, Alana (1992). "Archaism or Tradition?: The Decapitation Theme in Cupisnique and Moche Iconography". Latin American Antiquity. 3 (3): 206–220. JSTOR 971715. doi:10.2307/971715.

- ↑ UNESCO Chavin (Archaeological Site) Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 27 July 2014

- ↑ Pre-Inca Cultures Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. countrystudies.us.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence (2002). The Incas. Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 1405116765, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Peru The Incas Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Inca – All Empires Archived 20 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Inca" at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 November 2009) The National Foreign Language Center at the University of Maryland. 29 May 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Lovell, W. George (1992). "'Heavy Shadows and Black Night': Disease and Depopulation in Colonial Spanish America". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 426–443. JSTOR 2563354. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01968.x.

- ↑ Bakewell, Peter (1984). Miners of the Red Mountain: Indian labor in Potosi 1545–1650. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, ISBN 0826307698, p. 181.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Suárez, Margarita. Desafíos transatlánticos. Lima: FCE/IFEA/PUCP, 2001, pp. 252–253.

- 1 2 Conquest and Colony of Peru."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2014.. Retrieved 28 July 2014

- ↑ Andrien, Kenneth (1985). Crisis and decline: the Viceroyalty of Peru in the seventeenth century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 1597403237, pp. 200–202.

- ↑ Burkholder, Mark (1977). From impotence to authority: the Spanish Crown and the American audiencias, 1687–1808. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 0826202195, pp. 83–87.

- ↑ O'Phelan, Scarlett (1985). Rebellions and revolts in eighteenth century Peru and Upper Peru. Cologne: Böhlau, ISBN 3412010855, 9783412010850, p. 276.

- ↑ Peru Peru Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Gootenberg (1991) p. 12.

- ↑ Discover Peru (Peru cultural society). War of Independence Archived 21 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 28 July 2014

- ↑ Gootenberg (1993) pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Gootenberg (1993) p. 9.

- ↑ Klarén, Peter (2000). Peru: society and nationhood in the Andes. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 262–276, ISBN 0195069285.

- ↑ The Economist (17 October 2007), Peru.

- ↑ White, Gavin David (2009). "Displacement, decentralisation and reparation in post-conflict Peru". Forced Migration Review.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Article N° 112.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Article N° 122.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Article N° 90.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Articles N° 107–108.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Articles N° 146.

- ↑ Clark, Jeffrey. Building on quicksand. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Article N° 31.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Congreso de la República del Perú, Grupos Parlamentarios Archived 29 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ St John, Ronald Bruce (1992). The foreign policy of Peru. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, ISBN 1555873049, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ BBC News (4 November 2005), Peru–Chile border row escalates Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ Ministerio de Defensa, Libro Blanco de la Defensa Nacional. Ministerio de Defensa, 2005, 90.

- ↑ Ley N° 27178, Ley del Servicio Militar, Articles N° 29, 42 and 45.

- ↑ Ley N° 27867, Ley Orgánica de Gobiernos Regionales, Article N° 11.

- ↑ Ley N° 27867, Ley Orgánica de Gobiernos Regionales, Article N° 10.

- ↑ Ley N° 27867, Ley Orgánica de Gobiernos Regionales, Article N° 66.

- ↑ Monika Huber; Wolfgang Kaiser (February 2013). "Mixed Feelings". dandc.eu.

- ↑ Andes Handbook, Huascarán Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. 2 June 2002.

- ↑ Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú, El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico, p. 16.

- ↑ Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú, El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico, p. 31.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perú: Compendio Estadístico 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ "Application of Strontium Isotopes to Understanding the Hydrology and Paleohydrology of the Altiplano, Bolivia-Peru". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 194: 281–297. 2003. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00282-7.

- ↑ Oficina nacional de evaluación de recursos naturales (previous INRENA). "Inventario nacional de lagunas y represamientos" (PDF). INRENA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ↑ Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú, El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú, El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú, El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perú: Compendio Estadístico 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ "Peru Wildlife Information".

- 1 2 "Peru: Wildlife". Select Latin America. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ↑ Dillon, Michael O. "The solanaceae of the lomas formations of coastal peru and chile" (PDF). sacha.org. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ The World Bank, Data by country: Peru Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Peru Archived 5 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. CIA, The World Factbook

- ↑ BBC (31 July 2012), Peru country profile Archived 5 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Thorp, p. 4.

- ↑ Thorp, p. 321.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Evolución de la Pobreza en el Perú al 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ "Peru and the IMF". International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Thorp, pp. 318–319.

- ↑ Sheahan, John. Searching for a better society: the Peruvian economy from 1950. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999, ISBN 0271018720, p. 157.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Banco Central de Reserva, Producto bruto interno por sectores productivos 1951–2006 Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ 2006 figures. (in Spanish) Banco Central de Reserva, Memoria 2006 Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., p. 204. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Banco Central de Reserva, Memoria 2006 Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., pp. 15, 203. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, United States and Peru Sign Trade Promotion Agreement, 12 April 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ 2006 figures. (in Spanish) Banco Central de Reserva, Memoria 2006 Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., pp. 60–61. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ WHO/UNICEF JMP

- ↑ INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA E INFORMATICA. "PERÚ: ESTIMACIONES Y PROYECCIONES DE POBLACIÓN TOTAL POR SEXO DE LAS PRINCIPALES CIUDADES" (in Spanish).

- ↑ Cook, Noble David (1982) Demographic collapse: Indian Peru, 1520–1620. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0521239958.

- ↑ Vázquez, Mario (1970) "Immigration and mestizaje in nineteenth-century Peru", pp. 79–81 in Race and class in Latin America. Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0231032951

- ↑ Mörner, Magnus (1967), Race mixture in the history of Latin America, p. 131.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perú: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población, 1950–2050, pp. 37–38, 40.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil sociodemográfico del Perú, p. 13.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil sociodemográfico del Perú, p. 24.

- ↑ "Isolated Peru tribe threatened by outsiders Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.". USATODAY.com. 31 January 2012

- ↑ (in Spanish) Resonancias.org Archived 7 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. – Aboriginal languages of Peru

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil sociodemográfico del Perú, p. 132.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Perfil sociodemográfico del Perú, p. 93.

- ↑ Constitución Política del Perú, Article N° 17.

- ↑ "Decreto Supremo que aprueba el Reglamento de la Ley N° 29735, Ley que regula el uso, preservación, desarrollo, recuperación, fomento y difusión de las lenguas originarias del Perú, Decreto Supremo N° 004-2016-MC". Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ↑ Belaunde, Víctor Andrés (1983). Peruanidad. Lima: BCR, p. 472.

- ↑ Bailey, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Bailey, p. 263.

- ↑ Lucie-Smith, Edward (1993). Latin American art of the 20th century Archived 20 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0500203563, pp. 76–77, 145–146.

- ↑ Bayón, Damián (1998). "Art, c. 1920–c. 1980". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, ISBN 0521626269, pp. 425–428.

- ↑ Martin, "Literature, music and the visual arts, c. 1820–1870", pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Martin, "Narrative since c. 1920", pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Martin, "Narrative since c. 1920", pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Martin, "Narrative since c. 1920", pp. 186–188.

- ↑ Custer, pp. 17–22.

- ↑ Custer, pp. 25–38.

- ↑ Embassy of Peru in the United States, The Peruvian Gastronomy.peruvianembassy.us.

- ↑ Romero, Raúl (1999). "Andean Peru". In: John Schechter (ed.), Music in Latin American culture: regional tradition. New York: Schirmer Books, pp. 385–386.

- ↑ Olsen, Dale (2002). Music of El Dorado: the ethnomusicology of ancient South American cultures. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, ISBN 0813029201, pp. 17–22.

- ↑ Turino, Thomas (1993). "Charango". In: Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. New York: MacMillan Press Limited, vol. I, ISBN 0333378784, p. 340.

- ↑ Romero, Raúl (1985). "La música tradicional y popular". In: Patronato Popular y Porvenir, La música en el Perú. Lima: Industrial Gráfica, pp. pp. 243–245, 261–265.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of colonial Latin America. London: Phaidon, 2005, ISBN 0714841579.

- Constitución Política del Perú. 29 December 1993.

- Custer, Tony. The Art of Peruvian Cuisine. Lima: Ediciones Ganesha, 2003, ISBN 9972920305.

- Garland, Gonzalo. "Perú Siglo XXI", series of 11 working papers describing sectorial long-term forecasts, Grade, Lima, Peru, 1986-1987.

- Garland, Gonzalo. Peru in the 21st Century: Challenges and Possibilities in Futures: the Journal of Forecasting, Planning and Policy, Volume 22, Nº 4, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, England, May 1990.

- Gootenberg, Paul. (1991) Between silver and guano: commercial policy and the state in postindependence Peru. Princeton: Princeton University Press ISBN 0691023425.

- Gootenberg, Paul. (1993) Imagining development: economic ideas in Peru's "fictitious prosperity" of Guano, 1840–1880. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, 0520082907.

- Higgins, James (editor). The Emancipation of Peru: British Eyewitness Accounts, 2014. Online at https://sites.google.com/site/jhemanperu

- Instituto de Estudios Histórico–Marítimos del Perú. El Perú y sus recursos: Atlas geográfico y económico. Lima: Auge, 1996.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. "Perú: Compendio Estadístico 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2007. (8.31 MB). Lima: INEI, 2005.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perfil sociodemográfico del Perú. Lima: INEI, 2008.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población, 1950–2050. Lima: INEI, 2001.

- Ley N° 27178, Ley del Servicio Militar

DOC. 28 September 1999.

DOC. 28 September 1999. - Ley N° 27867, Ley Ley Orgánica de Gobiernos Regionales. 16 November 2002.

- Martin, Gerald. "Literature, music and the visual arts, c. 1820–1870". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 3–45.

- Martin, Gerald. "Narrative since c. 1920". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 133–225.

- Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. El nombre del Perú. Lima: Talleres Gráficos P.L. Villanueva, 1968.

- Thorp, Rosemary and Geoffrey Bertram. Peru 1890–1977: growth and policy in an open economy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978, ISBN 0231034334

Further reading

- Economy

- (in Spanish) Banco Central de Reserva. Cuadros Anuales Históricos.

- (in Spanish) Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú: Perfil de la pobreza por departamentos, 2004–2008. Lima: INEI, 2009.

- Concha, Jaime. "Poetry, c. 1920–1950". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 227–260.

External links

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Peru from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Peru". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Peru at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Peru

- Peru at DMOZ

- PeruLinks web directory

-

Wikimedia Atlas of Peru

Wikimedia Atlas of Peru -

Peru travel guide from Wikivoyage

Peru travel guide from Wikivoyage - (in Spanish) Web portal of the Peruvian Government

-

Geographic data related to Peru at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Peru at OpenStreetMap

.svg.png)

.jpg)

.svg.png)