Bohr–Einstein debates

The Bohr–Einstein debates were a series of public disputes about quantum mechanics between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Their debates are remembered because of their importance to the philosophy of science. An account of the debates was written by Bohr in an article titled "Discussions with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics".[1] Despite their differences of opinion regarding quantum mechanics, Bohr and Einstein had a mutual admiration that was to last the rest of their lives.[2]

The debates represent one of the highest points of scientific research in the first half of the twentieth century because it called attention to an element of quantum theory, quantum non-locality, which is central to our modern understanding of the physical world. The consensus view of professional physicists has been that Bohr proved victorious in his defense of quantum theory, and definitively established the fundamental probabilistic character of quantum measurement.

Pre-revolutionary debates

Einstein was the first physicist to say that Planck's discovery of the quantum (h) would require a rewriting of the laws of physics. To support his point, in 1905 he proposed that light sometimes acts as a particle which he called a light quantum (see photon and wave–particle duality). Bohr was one of the most vocal opponents of the photon idea and did not openly embrace it until 1925.[3] The photon appealed to Einstein because he saw it as a physical reality (although a confusing one) behind the numbers. Bohr disliked it because it made the choice of mathematical solution arbitrary. He did not like a scientist's having to choose between equations.[4]

1913 brought the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom, which made use of the quantum to explain the atomic spectrum. Einstein was at first skeptical, but quickly changed his mind and admitted his shift in mindset.

The quantum revolution

The quantum revolution of the mid-1920s occurred under the direction of both Einstein and Bohr, and their post-revolutionary debates were about making sense of the change. The shocks for Einstein began in 1925 when Werner Heisenberg introduced matrix equations that removed the Newtonian elements of space and time from any underlying reality. The next shock came in 1926 when Max Born proposed that mechanics were to be understood as a probability without any causal explanation.

Einstein rejected this interpretation. In a 1926 letter to Max Born, Einstein wrote: "I, at any rate, am convinced that He [God] does not throw dice."[5]

At the Fifth Solvay Conference held in October 1927 Heisenberg and Born concluded that the revolution was over and nothing further was needed. It was at that last stage that Einstein's skepticism turned to dismay. He believed that much had been accomplished, but the reasons for the mechanics still needed to be understood.[4]

Einstein's refusal to accept the revolution as complete reflected his desire to see developed a model for the underlying causes from which these apparent random statistical methods resulted. He did not reject the idea that positions in space-time could never be completely known but did not want to allow the uncertainty principle to necessitate a seemingly random, non-deterministic mechanism by which the laws of physics operated. Einstein himself was a statistical thinker but disagreed that no more needed to be discovered and clarified.[4] Bohr, meanwhile, was dismayed by none of the elements that troubled Einstein. He made his own peace with the contradictions by proposing a principle of complementarity that emphasized the role of the observer over the observed.[3]

Post-revolution: First stage

As mentioned above, Einstein's position underwent significant modifications over the course of the years. In the first stage, Einstein refused to accept quantum indeterminism and sought to demonstrate that the principle of indeterminacy could be violated, suggesting ingenious thought experiments which should permit the accurate determination of incompatible variables, such as position and velocity, or to explicitly reveal simultaneously the wave and the particle aspects of the same process.

The first serious attack by Einstein on the "orthodox" conception took place during the Fifth Solvay International Conference on Electrons and Photons in 1927. Einstein pointed out how it was possible to take advantage of the (universally accepted) laws of conservation of energy and of impulse (momentum) in order to obtain information on the state of a particle in a process of interference which, according to the principle of indeterminacy or that of complementarity, should not be accessible.

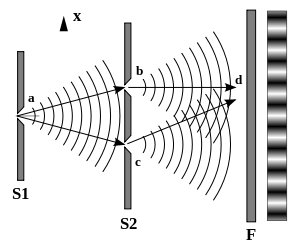

In order to follow his argumentation and to evaluate Bohr's response, it is convenient to refer to the experimental apparatus illustrated in figure A. A beam of light perpendicular to the X axis propagates in the direction z and encounters a screen S1 with a narrow (relative to the wavelength of the ray) slit. After having passed through the slit, the wave function diffracts with an angular opening that causes it to encounter a second screen S2 with two slits. The successive propagation of the wave results in the formation of the interference figure on the final screen F.

At the passage through the two slits of the second screen S2, the wave aspects of the process become essential. In fact, it is precisely the interference between the two terms of the quantum superposition corresponding to states in which the particle is localized in one of the two slits which implies that the particle is "guided" preferably into the zones of constructive interference and cannot end up in a point in the zones of destructive interference (in which the wave function is nullified). It is also important to note that any experiment designed to evidence the "corpuscular" aspects of the process at the passage of the screen S2 (which, in this case, reduces to the determination of which slit the particle has passed through) inevitably destroys the wave aspects, implies the disappearance of the interference figure and the emergence of two concentrated spots of diffraction which confirm our knowledge of the trajectory followed by the particle.

At this point Einstein brings into play the first screen as well and argues as follows: since the incident particles have velocities (practically) perpendicular to the screen S1, and since it is only the interaction with this screen that can cause a deflection from the original direction of propagation, by the law of conservation of impulse which implies that the sum of the impulses of two systems which interact is conserved, if the incident particle is deviated toward the top, the screen will recoil toward the bottom and vice versa. In realistic conditions the mass of the screen is so large that it will remain stationary, but, in principle, it is possible to measure even an infinitesimal recoil. If we imagine taking the measurement of the impulse of the screen in the direction X after every single particle has passed, we can know, from the fact that the screen will be found recoiled toward the top (bottom), whether the particle in question has been deviated toward the bottom or top, and therefore through which slit in S2 the particle has passed. But since the determination of the direction of the recoil of the screen after the particle has passed cannot influence the successive development of the process, we will still have an interference figure on the screen F. The interference takes place precisely because the state of the system is the superposition of two states whose wave functions are non-zero only near one of the two slits. On the other hand, if every particle passes through only the slit b or the slit c, then the set of systems is the statistical mixture of the two states, which means that interference is not possible. If Einstein is correct, then there is a violation of the principle of indeterminacy.

Bohr's response was to illustrate Einstein's idea more clearly using the diagram in Figure C. (Figure C shows a fixed screen S1 that is bolted down. Then try to imagine one that can slide up or down along a rod instead of a fixed bolt.) Bohr observes that extremely precise knowledge of any (potential) vertical motion of the screen is an essential presupposition in Einstein's argument. In fact, if its velocity in the direction X before the passage of the particle is not known with a precision substantially greater than that induced by the recoil (that is, if it were already moving vertically with an unknown and greater velocity than that which it derives as a consequence of the contact with the particle), then the determination of its motion after the passage of the particle would not give the information we seek. However, Bohr continues, an extremely precise determination of the velocity of the screen, when one applies the principle of indeterminacy, implies an inevitable imprecision of its position in the direction X. Before the process even begins, the screen would therefore occupy an indeterminate position at least to a certain extent (defined by the formalism). Now consider, for example, the point d in figure A, where the interference is destructive. It is obvious that any displacement of the first screen would make the lengths of the two paths, a–b–d and a–c–d, different from those indicated in the figure. If the difference between the two paths varies by half a wavelength, at point d there will be constructive rather than destructive interference. The ideal experiment must average over all the possible positions of the screen S1, and, for every position, there corresponds, for a certain fixed point F, a different type of interference, from the perfectly destructive to the perfectly constructive. The effect of this averaging is that the pattern of interference on the screen F will be uniformly grey. Once more, our attempt to evidence the corpuscular aspects in S2 has destroyed the possibility of interference in F, which depends crucially on the wave aspects.

It should be noted that, as Bohr recognized, for the understanding of this phenomenon "it is decisive that, contrary to genuine instruments of measurement, these bodies along with the particles would constitute, in the case under examination, the system to which the quantum-mechanical formalism must apply. With respect to the precision of the conditions under which one can correctly apply the formalism, it is essential to include the entire experimental apparatus. In fact, the introduction of any new apparatus, such as a mirror, in the path of a particle could introduce new effects of interference which influence essentially the predictions about the results which will be registered at the end." Further along, Bohr attempts to resolve this ambiguity concerning which parts of the system should be considered macroscopic and which not:

- In particular, it must be very clear that...the unambiguous use of spatiotemporal concepts in the description of atomic phenomena must be limited to the registration of observations which refer to images on a photographic lens or to analogous practically irreversible effects of amplification such as the formation of a drop of water around an ion in a dark room.

Bohr's argument about the impossibility of using the apparatus proposed by Einstein to violate the principle of indeterminacy depends crucially on the fact that a macroscopic system (the screen S1) obeys quantum laws. On the other hand, Bohr consistently held that, in order to illustrate the microscopic aspects of reality, it is necessary to set off a process of amplification, which involves macroscopic apparatuses, whose fundamental characteristic is that of obeying classical laws and which can be described in classical terms. This ambiguity would later come back in the form of what is still called today the measurement problem.

In a recent experiment, an apparatus to test this debate was developed and implemented. The test consisted of a free-floating molecular double slit and the momentum change of the atom scattering from it. The results of this experiment were compared to quantum mechanical, and semi-classical models. The results revealed that the classical description of the slits, used by Einstein, provides a surprisingly good description of the experimental results, even for a microscopic system, if the momentum transfer is not ascribed to a specific pathway but shared coherently and simultaneously between both.[6][7]

The principle of indeterminacy applied to time and energy

In many textbook examples and popular discussions of quantum mechanics, the principle of indeterminacy is explained by reference to the pair of variables position and velocity (or momentum). It is important to note that the wave nature of physical processes implies that there must exist another relation of indeterminacy: that between time and energy. In order to comprehend this relation, it is convenient to refer to the experiment illustrated in Figure D, which results in the propagation of a wave which is limited in spatial extension. Assume that, as illustrated in the figure, a ray which is extremely extended longitudinally is propagated toward a screen with a slit furnished with a shutter which remains open only for a very brief interval of time . Beyond the slit, there will be a wave of limited spatial extension which continues to propagate toward the right.

A perfectly monochromatic wave (such as a musical note which cannot be divided into harmonics) has infinite spatial extent. In order to have a wave which is limited in spatial extension (which is technically called a wave packet), several waves of different frequencies must be superimposed and distributed continuously within a certain interval of frequencies around an average value, such as . It then happens that at a certain instant, there exists a spatial region (which moves over time) in which the contributions of the various fields of the superposition add up constructively. Nonetheless, according to a precise mathematical theorem, as we move far away from this region, the phases of the various fields, at any specified point, are distributed causally and destructive interference is produced. The region in which the wave has non-zero amplitude is therefore spatially limited. It is easy to demonstrate that, if the wave has a spatial extension equal to (which means, in our example, that the shutter has remained open for a time where v is the velocity of the wave), then the wave contains (or is a superposition of) various monochromatic waves whose frequencies cover an interval which satisfies the relation:

Remembering that in the universal relation of Planck, frequency and energy are proportional:

it follows immediately from the preceding inequality that the particle associated with the wave should possess an energy which is not perfectly defined (since different frequencies are involved in the superposition) and consequently there is indeterminacy in energy:

From this it follows immediately that:

which is the relation of indeterminacy between time and energy.

Einstein's second criticism

At the sixth Congress of Solvay in 1930, the indeterminacy relation just discussed was Einstein's target of criticism. His idea contemplates the existence of an experimental apparatus which was subsequently designed by Bohr in such a way as to emphasize the essential elements and the key points which he would use in his response.

Einstein considers a box (called Einstein's box; see figure) containing electromagnetic radiation and a clock which controls the opening of a shutter which covers a hole made in one of the walls of the box. The shutter uncovers the hole for a time which can be chosen arbitrarily. During the opening, we are to suppose that a photon, from among those inside the box, escapes through the hole. In this way a wave of limited spatial extension has been created, following the explanation given above. In order to challenge the indeterminacy relation between time and energy, it is necessary to find a way to determine with adequate precision the energy that the photon has brought with it. At this point, Einstein turns to his celebrated relation between mass and energy of special relativity: . From this it follows that knowledge of the mass of an object provides a precise indication about its energy. The argument is therefore very simple: if one weighs the box before and after the opening of the shutter and if a certain amount of energy has escaped from the box, the box will be lighter. The variation in mass multiplied by will provide precise knowledge of the energy emitted. Moreover, the clock will indicate the precise time at which the event of the particle’s emission took place. Since, in principle, the mass of the box can be determined to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, the energy emitted can be determined with a precision as accurate as one desires. Therefore, the product can be rendered less than what is implied by the principle of indeterminacy.

The idea is particularly acute and the argument seemed unassailable. It's important to consider the impact of all of these exchanges on the people involved at the time. Leon Rosenfeld, a scientist who had participated in the Congress, described the event several years later:

- It was a real shock for Bohr...who, at first, could not think of a solution. For the entire evening he was extremely agitated, and he continued passing from one scientist to another, seeking to persuade them that it could not be the case, that it would have been the end of physics if Einstein were right; but he couldn't come up with any way to resolve the paradox. I will never forget the image of the two antagonists as they left the club: Einstein, with his tall and commanding figure, who walked tranquilly, with a mildly ironic smile, and Bohr who trotted along beside him, full of excitement...The morning after saw the triumph of Bohr.

Bohr's Triumph

The "Triumph of Bohr" consisted in his demonstrating, once again, that Einstein's subtle argument was not conclusive, but even more so in the way that he arrived at this conclusion by appealing precisely to one of the great ideas of Einstein: the principle of equivalence between gravitational mass and inertial mass, together with the time dilation of special relativity, and a consequence of these--the Gravitational redshift. Bohr showed that, in order for Einstein's experiment to function, the box would have to be suspended on a spring in the middle of a gravitational field. In order to obtain a measurement of the weight of the box, a pointer would have to be attached to the box which corresponded with the index on a scale. After the release of a photon, a mass could be added to the box to restore it to its original position and this would allow us to determine the energy that was lost when the photon left. The box is immersed in a gravitational field of strength , and the gravitational redshift affects the speed of the clock, yielding uncertainty in the time required for the pointer to return to its original position. Bohr gave the following calculation establishing the uncertainty relation .

Let the uncertainty in the mass be denoted by . Let the error in the position of the pointer be . Adding the load to the box imparts a momentum that we can measure with an accuracy , where ≈ . Clearly , and therefore . By the redshift formula (which follows from the principle of equivalence and the time dilation), the uncertainty in the time is , and , and so . We have therefore proven the claimed .[8][9]

Post-revolution: Second stage

The second phase of Einstein's "debate" with Bohr and the orthodox interpretation is characterized by an acceptance of the fact that it is, as a practical matter, impossible to simultaneously determine the values of certain incompatible quantities, but the rejection that this implies that these quantities do not actually have precise values. Einstein rejects the probabilistic interpretation of Born and insists that quantum probabilities are epistemic and not ontological in nature. As a consequence, the theory must be incomplete in some way. He recognizes the great value of the theory, but suggests that it "does not tell the whole story", and, while providing an appropriate description at a certain level, it gives no information on the more fundamental underlying level:

- I have the greatest consideration for the goals which are pursued by the physicists of the latest generation which go under the name of quantum mechanics, and I believe that this theory represents a profound level of truth, but I also believe that the restriction to laws of a statistical nature will turn out to be transitory....Without doubt quantum mechanics has grasped an important fragment of the truth and will be a paragon for all future fundamental theories, for the fact that it must be deducible as a limiting case from such foundations, just as electrostatics is deducible from Maxwell's equations of the electromagnetic field or as thermodynamics is deducible from statistical mechanics.

These thoughts of Einstein would set off a line of research into hidden variable theories, such as the Bohm interpretation, in an attempt to complete the edifice of quantum theory. If quantum mechanics can be made complete in Einstein's sense, it cannot be done locally; this fact was demonstrated by John Stewart Bell with the formulation of Bell's inequality in 1964.

Post-revolution: Third stage

The argument of EPR

In 1935 Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen developed an argument, published in the magazine Physical Review with the title Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?, based on an entangled state of two systems. Before coming to this argument, it is necessary to formulate another hypothesis that comes out of Einstein's work in relativity: the principle of locality. The elements of physical reality which are objectively possessed cannot be influenced instantaneously at a distance.

The argument of EPR was in 1957 picked up by David Bohm and Yakir Aharonov in a paper published in Physical Review with the title Discussion of Experimental Proof for the Paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky. The authors re-formulated the argument in terms of an entangled state of two particles, which can be summarized as follows:

1) Consider a system of two photons which at time t are located, respectively, in the spatially distant regions A and B and which are also in the entangled state of polarization described below:

2) At time t the photon in region A is tested for vertical polarization. Suppose that the result of the measurement is that the photon passes through the filter. According to the reduction of the wave packet, the result is that, at time t + dt, the system becomes

3) At this point, the observer in A who carried out the first measurement on photon 1, without doing anything else that could disturb the system or the other photon ("assumption (R)", below), can predict with certainty that photon 2 will pass a test of vertical polarization. It follows that photon 2 possesses an element of physical reality: that of having a vertical polarization.

4) According to the assumption of locality, it cannot have been the action carried out in A which created this element of reality for photon 2. Therefore, we must conclude that the photon possessed the property of being able to pass the vertical polarization test before and independently of the measurement of photon 1.

5) At time t, the observer in A could have decided to carry out a test of polarization at 45°, obtaining a certain result, for example, that the photon passes the test. In that case, he could have concluded that photon 2 turned out to be polarized at 45°. Alternatively, if the photon did not pass the test, he could have concluded that photon 2 turned out to be polarized at 135°. Combining one of these alternatives with the conclusion reached in 4, it seems that photon 2, before the measurement took place, possessed both the property of being able to pass with certainty a test of vertical polarization and the property of being able to pass with certainty a test of polarization at either 45° or 135°. These properties are incompatible according to the formalism.

6) Since natural and obvious requirements have forced the conclusion that photon 2 simultaneously possesses incompatible properties, this means that, even if it is not possible to determine these properties simultaneously and with arbitrary precision, they are nevertheless possessed objectively by the system. But quantum mechanics denies this possibility and it is therefore an incomplete theory.

Bohr's response

Bohr's response to this argument was published, five months later than the original publication of EPR, in the same magazine Physical Review and with exactly the same title as the original.[10] The crucial point of Bohr's answer is distilled in a passage which he later had republished in Paul Arthur Schilpp's book Albert Einstein, scientist-philosopher in honor of the seventieth birthday of Einstein. Bohr attacks assumption (R) of EPR by stating:

- The statement of the criterion in question is ambiguous with regard to the expression "without disturbing the system in any way". Naturally, in this case no mechanical disturbance of the system under examination can take place in the crucial stage of the process of measurement. But even in this stage there arises the essential problem of an influence on the precise conditions which define the possible types of prediction which regard the subsequent behaviour of the system...their arguments do not justify their conclusion that the quantum description turns out to be essentially incomplete...This description can be characterized as a rational use of the possibilities of an unambiguous interpretation of the process of measurement compatible with the finite and uncontrollable interaction between the object and the instrument of measurement in the context of quantum theory.

Post-revolution: Fourth stage

In his last writing on the topic, Einstein further refined his position, making it completely clear that what really disturbed him about the quantum theory was the problem of the total renunciation of all minimal standards of realism, even at the microscopic level, that the acceptance of the completeness of the theory implied. Although the majority of experts in the field agree that Einstein was wrong, the current understanding is still not complete (see Interpretation of quantum mechanics). There is no scientific consensus that determinism would have been refuted.[11][12]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bohr–Einstein debates |

- Afshar's experiment

- Bell test experiments

- Bell's theorem

- Complementarity

- Copenhagen interpretation

- Double-slit experiment

- Invariant set postulate

- Quantum eraser

- Schrödinger's cat

- Uncertainty principle

- Wheeler's delayed choice experiment

References

- ↑ Bohr N. "Discussions with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics". The Value of Knowledge: A Miniature Library of Philosophy. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 2010-08-30. From Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist (1949), publ. Cambridge University Press, 1949. Niels Bohr's report of conversations with Einstein.

- ↑ González AM. "Albert Einstein". Donostia International Physics Center. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- 1 2 Pais

- 1 2 3 Bolles

- ↑ (Einstein 1969). A reprint of this book was published by Edition Erbrich in 1982, ISBN 3-88682-005-X

- ↑ Momentum Transfer to a Free Floating Double Slit: Realization of a Thought Experiment from the Einstein-Bohr Debates, L. Ph. H. Schmidt et al. Physical Review Letters Week ending 2013

- ↑ If more experiments begin to confirm this view – that a particle is in fact equally present (so, in a way, spread) in all the points of an orbital and that all such points indeed interact with the environment – it could possibly undermine the Copenhagen interpretation and favour the De Broglie-Bohm theory, which has assumed such spread of properties (e.g. mass, charge). A deterministic theory (through a kind of guiding towards the probability centre) could possibly explain better and more universally than a fully indeterministic one how can a particle (i.e. a common wavefunction for a continuum of points) remain coherent in time.

- ↑ Abraham Pais, "Subtle is the Lord...", The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, p.447-8, 1982

- ↑ Niels Bohr in Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist (P.Schilpp, Editor), p.199. Tudor, New York, 1949

- ↑ http://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.48.696

- ↑ Bishop, Robert C. (2011). "Chaos, Indeterminism, and Free Will". In Kane, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Free Wil (Second ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-19-539969-1. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

The key question is whether to understand the nature of this probability as epistemic or ontic. Along epistemic lines, one possibility is that there is some additional factor (i.e., a hidden mechanism) such that once we discover and understand this factor, we would be able to predict the observed behavior of the quantum stoplight with certainty (physicists call this approach a "hidden variable theory"; see, e.g., Bell 1987, 1-13, 29-39; Bohm 1952a, 1952b; Bohm and Hiley 1993; Bub 1997, 40-114, Holland 1993; see also the preceding essay in this volume by Hodgson). Or perhaps there is an interaction with the broader environment (e.g., neighboring buildings, trees) that we have not taken into account in our observations that explains how these probabilities arise (physicists call this approach decoherence or consistent histories15). Under either of these approaches, we would interpret the observed indeterminism in the behavior of stoplights as an expression of our ignorance about the actual workings. Under an ignorance interpretation, indeterminism would not be a fundamental feature of quantum stoplights, but merely epistemic in nature due to our lack of knowledge about the system. Quantum stoplights would turn to be deterministic after all.

- ↑ Baggott, Jim E. (2004). "Complementarity and Entanglement". Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy, and the Meaning of Quantum Theory. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-19-852536-2. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

So, was Einstein wrong? In the sense that the EPR paper argued in favour of an objective reality for each quantum particle in an entangled pair independent of the other and of the measuring device, the answer must be yes. But if we take a wider view and ask instead if Einstein was wrong to hold to the realist's belief that the physics of the universe should be objective and deterministic, we must acknowledge that we cannot answer such a question. It is in the nature of theoretical science that there can be no such thing as certainty. A theory is only 'true' for as long as the majority of the scientific community maintain a consensus view that the theory is the one best able to explain the observations. And the story of quantum theory is not over yet.

Further reading

- Boniolo, G., (1997) Filosofia della Fisica, Mondadori, Milan.

- Bolles, Edmund Blair (2004) Einstein Defiant, Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C.

- Born, M. (1973) The Born Einstein Letters, Walker and Company, New York, 1971.

- Ghirardi, Giancarlo, (1997) Un'Occhiata alle Carte di Dio, Il Saggiatore, Milan.

- Pais, A., (1986) Subtle is the Lord... The Science and Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1982.

- Shilpp, P.A., (1958) Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, Northwestern University and Southern Illinois University, Open Court, 1951.