Eighty Years' War

| Eighty Years' War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

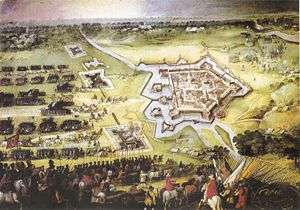

Relief of Leiden after the siege, 1574 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~100,000 Dutch killed[1] (1568–1609) | Unknown | ||||||

The Eighty Years' War (Dutch: Tachtigjarige Oorlog; Spanish: Guerra de los Ochenta Años) or Dutch War of Independence (1568–1648)[2] was a revolt of the Seventeen Provinces against the political and religious hegemony of Philip II of Spain, the sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands. After the initial stages, Philip II deployed his armies and regained control over most of the rebelling provinces. Under the leadership of the exiled William the Silent, the northern provinces continued their resistance. They eventually were able to oust the Habsburg armies, and in 1581 they established the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The war continued in other areas, although the heartland of the republic was no longer threatened; this included the beginnings of the Dutch Colonial Empire, which at the time were conceived as carrying overseas the war with Spain. After a 12-year truce, hostilities broke out again around 1619, which can be said to coincide with the Thirty Years' War. An end was reached in 1648 with the Peace of Münster (a treaty part of the Peace of Westphalia), when the Dutch Republic was recognised as an independent country (though the fact of its being such was evident long before).

Causes of the war

In the decades preceding the war, the Dutch became increasingly discontented with Habsburg rule. A major cause of this discontent was heavy taxation imposed on the population, while support and guidance from the government was hampered by the size of the Habsburg empire. At that time, the Seventeen Provinces were known in the empire as De landen van herwaarts over and in French as Les pays de par deça - "those lands around there". The Dutch provinces were continually criticised for acting without permission from the throne, while it was impractical for them to gain permission for actions, as requests sent to the throne would take at least four weeks for a response to return. The presence of Spanish troops under the command of the Duke of Alba, brought in to oversee order,[3] further amplified this unrest.

Spain also attempted a policy of strict religious uniformity for the Catholic Church within its domains, and enforced it with the Inquisition. The Reformation meanwhile produced a number of Protestant denominations, which gained followers in the Seventeen Provinces. These included the Lutheran movement of Martin Luther, the Anabaptist movement of the Dutch reformer Menno Simons, and the Reformed teachings of John Calvin. This growth led to the 1566 Beeldenstorm, the "Iconoclastic Fury", in which many churches in northern Europe were stripped of their Catholic statuary and religious decoration.

Prelude

In October 1555, Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire began the gradual abdication of his several crowns. His son Philip II took over as sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands,[4] which at the time was a personal union of seventeen provinces with little in common beyond their sovereign and a constitutional framework. This framework, assembled during the preceding reigns of Burgundian and Habsburg rulers, divided power between city governments, local nobility, provincial States, royal stadtholders, the States General of the Netherlands, and the central government (possibly represented by a Regent) assisted by three councils: the Council of State, the Privy Council and the Council of Finances. The balance of power was heavily weighted toward the local and regional governments.[5]

Philip did not govern in person but appointed Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy as governor-general to lead the central government. In 1559 he appointed his half-sister Margaret of Parma as the first Regent, who governed in close co-operation with Dutch nobles like William, Prince of Orange, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn, and Lamoral, Count of Egmont. Philip introduced a number of councillors in the Council of State, foremost among these Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, a French-born cardinal who gained considerable influence in the Council, much to the chagrin of the Dutch council members.

When Philip left for Spain in 1559 political tension was increased by religious policies. Not having the liberal-mindedness of his father Charles V, Philip was a fervent enemy of the Protestant movements of Martin Luther, John Calvin, and the Anabaptists. Charles had outlawed heresy in special placards that made it a capital offence, to be prosecuted by a Dutch version of the Inquisition, leading to the executions of over 1,300 people between 1523 and 1566.[7] Towards the end of Charles' reign enforcement had reportedly become lax. Philip, however, insisted on rigorous enforcement, which caused widespread unrest.[8] To support and strengthen the attempts at Counter-Reformation Philip launched a wholesale organisational reform of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands in 1559, which resulted in the inclusion of fourteen dioceses instead of the old three. The new hierarchy was to be headed by Granvelle as archbishop of the new archdiocese of Mechelen. The reform was especially unpopular with the old church hierarchy, as the new dioceses were to be financed by the transfer of a number of rich abbeys.[9] Granvelle became the focus of the opposition against the new governmental structures and the Dutch nobles under the leadership of Orange engineered his recall in 1564.

After the recall of Granvelle, Orange persuaded Margaret and the Council to ask for a moderation of the placards against heresy. Philip delayed his response, and in this interval the opposition to his religious policies gained more widespread support. Philip finally rejected the request for moderation in his Letters from the Segovia Woods of October 1565. In response, a group of members of the lesser nobility, among whom were Louis of Nassau, a younger brother of Orange, and the brothers John and Philip of St. Aldegonde, prepared a petition for Philip that sought the abolition of the Inquisition. This Compromise of Nobles was supported by about 400 nobles, both Catholic and Protestant, and was presented to Margaret on 5 April 1566. Impressed by the massive support for the compromise, she suspended the placards, awaiting Philip's final ruling.[10]

First forty years (1566–1609)

The first half of the Eighty Years' War between the Spanish Empire and the Dutch Republic was fought between 1566 and 1609. When the Twelve Years' Truce was signed in 1609, ending this first phase of war, the northern Netherlands had achieved de facto independence.

Twelve Years' Truce

The military upkeep and decreased trade had put both Spain and the Dutch Republic under financial strain. To alleviate conditions, a ceasefire was signed in Antwerp on 9 April 1609, marking the end of the Dutch Revolt and the beginning of the Twelve Years' Truce.[11]

Although there was peace on an international level, political unrest took hold of Dutch domestic affairs. What had started as a theological quarrel resulted in riots between Remonstrants (Arminians) and Counter-Remonstrants (Gomarists). In general, regents would support the former and civilians the latter. Even the government got involved, with land's advocate Johan van Oldenbarnevelt taking the side of the Remonstrants and stadtholder Maurice of Nassau their opponents. In the end, the Synod of Dort condemned the Remonstrants for heresy and excommunicated them from the national Public Church. Van Oldenbarnevelt was sentenced to death, together with his ally Gilles van Ledenberg, while two other Remonstrant allies, Rombout Hogerbeets and Hugo Grotius received life imprisonment.[12]

Resumption of the war

Dutch intervention in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War (1619–1621)

Van Oldenbarnevelt had no ambition to have the Republic become the leading power of Protestant Europe, and he had shown admirable restraint when, in 1614, the Republic had felt constrained to intervene militarily in the Jülich-Cleves crisis opposite Spain. Though there had been a danger of armed conflict between the Spanish and Dutch forces involved in the crisis, both sides took care to avoid each other, respecting each other's spheres of influence.[13]

The new regime in The Hague felt differently, however. While civil war was avoided in the Republic, a civil war did start in the Bohemian Kingdom with the Second defenestration of Prague on 23 May 1618. The Bohemian insurgents were now pitted against their king, Ferdinand, who would soon succeed his uncle Matthias (the former States General governor-general of the Netherlands) as Holy Roman Emperor. They cast about for support in this struggle and on the Protestant side only the Republic was able and willing to provide it. This took the form of support for Frederick V, Elector Palatine, a nephew of Prince Maurice[14] and a son-in-law of James I, when Frederick accepted the Crown of Bohemia the insurgents offered him (he was crowned on 4 November 1619). His father-in-law had sought to restrain him from doing this, warning that he could not count on English aid, but Maurice encouraged him in every way, providing a large subsidy and promising Dutch armed assistance. The Dutch had therefore a large role in precipitating the Thirty Years' War.[15]

Maurice's motivation was the desire to manoeuvre the Republic into a better position should the war with Spain resume after the expiration of the Truce in 1621. Renewal of the Truce was a distinct possibility, but it had become less likely, as both in Spain and in the Republic more hard-line factions had come to power.[16] Though civil war had been avoided in the Republic, national unity had been bought with much bitterness on the losing Remonstrant side, and Maurice for the moment had to garrison several former Remonstrant-dominated cities to guard against insurrection. This encouraged the Spanish government, perceiving internal weakness in the Republic, to choose a bolder policy in the Bohemian question than they otherwise might have done. The Bohemian war therefore soon degenerated into a proxy war between Spain and the Republic. Even after the Battle of White Mountain of November 1620, which ended disastrously for the Protestant army (one-eighth of which was in the Dutch pay), the Dutch continued to support Frederick militarily, both in Bohemia and in the Palatinate. Maurice also provided diplomatic support, pressing both the Protestant German princes and James I to come to Frederick's aid. When James sent 4,000 English troops in September 1620, those were armed and transported by the Dutch, and their advance covered by a Dutch cavalry column.[17]

In the end the Dutch intervention was in vain. After just a few months, Frederick and his wife Elizabeth fled into exile at The Hague, where they became known as the Winter King and Queen for their brief reign. Maurice pressed Frederick in vain to at least defend the Palatinate against the Spanish troops under Spinola and Tilly. This round of the war went to Spain and the Imperial forces in Germany. James held this against Maurice for his incitement of the losing side with promises that he could not keep.[18]

There was continual contact between Maurice and the government in Brussels during 1620 and 1621 regarding a possible renewal of the Truce. Albert was in favour of it, especially after Maurice falsely gave him the impression that a peace would be possible on the basis of a token recognition by the Republic of the sovereignty of the king of Spain. When Albert sent the chancellor of Brabant, Petrus Peckius, to The Hague to negotiate with the States General on this basis, he fell into this trap and innocently started talking about this recognition, instantly alienating his hosts. Nothing was as certain to unite the northern provinces as the suggestion that they should abandon their hard-fought sovereignty. If this incident had not come up, the negotiations might well have been successful as a number of the provinces were amenable to simply renewing the Truce on the old terms. Now the formal negotiations were broken off, however, and Maurice was authorised to conduct further negotiations in secret. His attempts to get a better deal met with counter-demands from the new Spanish government for more substantive Dutch concessions. The Spaniards demanded Dutch evacuation of the West and East Indies; lifting of the restrictions on Antwerp's trade by way of the Scheldt; and toleration of the public practice of the Catholic religion in the Republic. These demands were unacceptable to Maurice and the Truce expired in April 1621.[19]

The war did not immediately resume, however. Maurice continued sending secret offers to Isabella after Albert had died in July 1621,[20] through the intermediary of the Flemish painter and diplomat Peter Paul Rubens. Though the contents of these offers (which amounted to a version of the concessions demanded by Spain) were not known in the Republic, the fact of the secret negotiations became known. Proponents of restarting the war were disquieted, like the investors in the Dutch West India Company, which after a long delay was finally about to be founded, with a main objective of bringing the war to the Spanish Americas. Opposition against the peace feelers therefore mounted, and nothing came of them.[21]

The Republic under siege (1621–1629)

Another reason the war did not immediately resume was that king Philip III died shortly before the Truce ended. He was succeeded by his 16-year-old son Philip IV, and the new government under Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares had to get settled. The view in the Spanish government was that the Truce had been ruinous to Spain in an economic sense. In this view the Truce had enabled the Dutch to gain very unequal advantages in the trade with the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean, owing to their mercantile prowess. On the other hand, the continued blockade of Antwerp had contributed to that city's steep decline in importance (hence the demand for the lifting of the closing of the Scheldt). The shift in the terms of trade between Spain and the Republic had resulted in a permanent trade deficit for Spain, which naturally translated into a drain of Spanish silver to the Republic. The Truce had also given further impetus to the Dutch penetration of the East Indies, and in 1615 a naval expedition under Joris van Spilbergen had raided the West-Coast of Spanish South-America. Spain felt threatened by these incursions and wanted to put a stop to them. Finally, the economic advantages had given the Republic the financial wherewithal to build a large navy during the Truce and to enlarge its standing army to a size where it could rival the Spanish military might. This increased military power appeared to be directed principally to thwart Spain's policy objectives, as witnessed by the Dutch interventions in Germany in 1614 and 1619, and the Dutch alliance with the enemies of Spain in the Mediterranean, like Venice and the Sultan of Morocco. The three conditions Spain had set for a continuation of the Truce had been intended to remedy these disadvantages of the Truce (the demand for freedom of worship for Catholics being made as a matter of principle, but also to mobilise the still sizeable Catholic minority in the Republic and so destabilise it politically).[22]

Despite the unfortunate impression the opening speech of chancellor Peckius had made at the negotiations about the renewal of the Truce, the objective of Spain and the regime in Brussels was not a war of reconquest of the Republic. Instead the options considered in Madrid were either a limited exercise of the force of weapons, to capture a few of the strategic points the republic had recently acquired (like Cleves), combined with measures of economic warfare, or reliance on economic warfare alone. Spain opted for the first alternative. Immediately after the expiration of the Truce in April 1621, all Dutch ships were ordered out of Spanish ports, and the stringent trade embargoes of before 1609 were renewed. After an interval to rebuild the strength of the Army of Flanders, Spinola opened a number of land offensives, in which he captured the fortress of Jülich (garrisoned by the Dutch since 1614) in 1622, and Steenbergen in Brabant, before laying siege to the important fortress city of Bergen-op-Zoom. This proved a costly fiasco as Spinola's besieging army of 18,000 melted away through disease and desertion. He therefore had to lift the siege after a few months. The strategic import of this humiliating experience was that the Spanish government now concluded that besieging the strong Dutch fortresses was a waste of time and money and decided to henceforth solely depend on the economic warfare weapon. The subsequent success of Spinola's siege of Breda did not change this decision, and Spain adopted a defensive stance militarily in the Netherlands.[23]

.jpg)

However, the economic warfare was intensified in a way that amounted to a veritable siege of the Republic as a whole. In the first place, the naval war intensified. The Spanish navy harassed Dutch shipping, which had to sail through the Strait of Gibraltar to Italy and the Levant, thereby forcing the Dutch to sail in convoys with naval escorts. The cost of this was borne by the merchants in the form of a special tax, used to finance the Dutch navy, but this increased the shipping rates the Dutch had to charge, and their maritime insurance premiums also were higher, thus making Dutch shipping less competitive. Spain also increased the presence of its navy in Dutch home waters, in the form of the armada of Flanders, and the great number of privateers, the Dunkirkers, both based in the Southern Netherlands. Though these Spanish naval forces were not strong enough to contest Dutch naval supremacy, Spain waged a very successful Guerre de Course, especially against the Dutch herring fisheries, despite attempts by the Dutch to blockade the Flemish coast.[24]

The herring trade, an important pillar of the Dutch economy, was hurt much by the other Spanish forms of economic warfare, the embargo on salt for preserving herring, and the blockade of the inland waterways to the Dutch hinterland, which were an important transportation route for Dutch transit trade. The Dutch were used to procuring their salt from Portugal and the Caribbean islands. Alternative salt supplies were available from France, but the French salt had a high magnesium content, which made it less suitable for herring preservation. When the supplies in the Spanish sphere of influence were cut off, the Dutch economy was therefore dealt a heavy blow. The salt embargo was just a part of the more general embargo on Dutch shipping and trade that Spain instituted after 1621. The bite of this embargo grew only gradually, because the Dutch at first tried to evade it by putting their trade in neutral bottoms, like the ships of the Hanseatic League and England. Spanish merchants tried to evade it, as the embargo also did great harm to Spanish economic interests, even to the extent that for a time a famine threatened in Spanish Naples when the Dutch-carried grain trade was cut off.[25] Realizing that the local authorities often sabotaged the embargo, the Spanish crown built up an elaborate enforcement apparatus, the Almirantazgo de los países septentrionales (Admiralty of the northern countries) in 1624 to make it more effective. Part of the new system was a network of inspectors in neutral ports who inspected neutral shipping for goods with a Dutch connection and supplied certificates that protected neutral shippers against confiscation in Spanish ports. The English and Hanseatics were only too happy to comply, and so contributed to the effectiveness of the embargo.[26]

The embargo grew to an effective direct and indirect impediment for Dutch trade, as not only the direct trade between the Amsterdam Entrepôt and the lands of the Spanish empire was affected, but also the parts of Dutch trade that indirectly depended on it: Baltic grain and naval stores destined for Spain were now provided by others, depressing the Dutch trade with the Baltic area, and the carrying trade between Spain and Italy now shifted to English shipping. The embargo was a double-edged sword, however, as some Spanish and Portuguese export activities likewise collapsed as a consequence (such as the Valencian and Portuguese salt exports).[27]

Spain was also able to physically close off inland waterways for Dutch river traffic after 1625. The Dutch were thus also deprived of their important transit trade with the neutral Prince-Bishopric of Liège (then not a part of the Southern Netherlands) and the German hinterland. Dutch butter and cheese prices collapsed as a result of this blockade (and rose steeply in the affected import areas), as did wine and herring prices (the Dutch monopolised the French wine trade at the time). The steep price rises in the Spanish Netherlands were sometimes accompanied by food shortages, however, leading to an eventual relaxation of this embargo. It was eventually abandoned, because it deprived the Brussels authorities from important revenues from custom duties.[28]

The economic warfare measures of Spain were effective in the sense that they depressed economic activity in the Netherlands, thereby also depressing Dutch fiscal resources to finance the war effort, but also by structurally altering European trade relations, at least until the end of the war, after which they reverted in favour of the Dutch. Neutrals benefited, but both the Dutch and the Spanish areas suffered economically, though not uniformly, as some industrial areas benefited from the artificial restriction of trade, which had a protectionist effect. The "new draperies" textile industry in Holland permanently lost terrain to its competitors in Flanders and England, though this was compensated for by a shift to more expensive high-quality woollens.[29] Nevertheless, the economic pressure and the slump of trade and industry it caused was not sufficient to bring the Republic to its knees. There were a number of reasons for this. The chartered companies, both VOC and WIC, provided employment on a large enough scale to compensate for the slump in other forms of trade and their trade brought great revenues. Supplying the armies, both in the Netherlands and in Germany, proved a boon for the agricultural areas in the Dutch inland provinces.[30]

The fiscal situation of the Dutch government also improved after the death of Maurice in 1625. He had been too successful in gathering all reins of government in his own hands after his coup in 1618. He completely dominated Dutch politics and diplomacy in his first years afterwards, even monopolising the abortive peace talks before the expiration of the Truce. Likewise the political Counter-Remonstrants were temporarily in total control, but the downside was that his government was overextended, with too few people doing the heavy lifting at the local level, which was essential to make the government machine run smoothly in the highly decentralised Dutch polity. Holland's conventional role as leader of the political process was temporarily vacated, as Holland as a power center was eliminated. Maurice had to do everything by himself with his small band of aristocratic managers in the States General. This situation deteriorated even more when he had to spend long periods in the field as commander-in-chief, during which he was unable to personally direct affairs in The Hague. His health soon deteriorated, also detracting from his efficacy as a political and military leader. The regime, depending on Maurice's personal qualities as a virtual dictator, therefore came under unbearable strain.[31]

Not surprisingly, in the period up to his death the strategic and military position of the Republic deteriorated. It had to increase the standing army to 48,000 men in 1622, just to hold the defensive ring of fortresses, while Spain increased the Army of Flanders to 60,000 men at the same time. This put a great strain on the Republic's finances at a time when tax rates were already dangerously high. Yet at the same time the Republic had no other option than to sustain the imploding German Protestant forces financially. For that reason the Dutch paid for the army of Count Ernst von Mansfeld that was cowering against the Dutch border in East Friesland after its defeats against the Spanish and Imperial forces; it was hoped that in this way a complete encirclement of the Republic could be avoided. For a while the Republic pinned its hope on Christian the Younger of Brunswick. However, his Dutch-financed army was crushed at Stadtlohn, near the Dutch border by the forces of the Catholic League under Tilly in August 1623. This setback necessitated a reinforcement of the Dutch IJssel line. Spinola, however, failed to take advantage of the new situation, lulled into complacency by Maurice's unceasing peace-feelers. He was back in 1624, however, besieging Breda, and Dutch morale slumped, despite the diplomatic success of the Treaty of Compiègne with Louis XIII of France, in which the latter agreed to support the Dutch military effort with an annual subsidy of a million guilders (7% of the Dutch war budget).[32]

Maurice died in April 1625, aged 58, and was succeeded as Prince of Orange and captain-general of the Union by his half-brother Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange. It took several months, however, to obtain his appointment as stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland, as it took time to agree on the terms of his commission. This deprived the regime of leadership in a crucial time. During this time the moderate Calvinist regents staged a return in Holland at the expense of the radical Counter-Remonstrants. This was an important development, as Frederick Henry could not lean exclusively on the latter faction, but instead took a position "above the parties", playing the two factions against one another. A side effect of this was that more normal political relations returned to the Republic, with Holland returning to its central political position. Also, the persecution of the Remonstrants now abated with the Prince's connivance, and with this renewed climate of tolerance, political stability in the Republic also improved.[33]

This improvement in internal affairs helped the Republic overcome the difficult years of the sharpest economic warfare phase. During the lull in the military pressure by Spain after the fall of Breda in 1625, the Republic was able to steadily increase its standing army, owing to its improved financial situation. This enabled the new stadtholder of Friesland and Groningen, Ernst Casimir, to recapture Oldenzaal, forcing the Spanish troops to evacuate Overijssel. Diplomatically, the situation improved once England entered the war in 1625 as an ally. Frederick Henry cleared the Spaniards from eastern Gelderland in 1627 after recapturing Grol. The Dutch victory in the Battle in the Bay of Matanzas in 1628, in which a Spanish treasure fleet was captured by Piet Pieterszoon Hein, contributed even more to the improving fiscal situation, at the same time depriving Spain of much needed money. However, the greatest contribution to the improvement of the Dutch position in 1628 was that Spain had overextended itself again when it participated in the War of the Mantuan Succession. This caused such a depletion of Spanish troops and financial resources in the theatre of war in the Netherlands that the Republic for the time being achieved a strategic superiority: the Army of Flanders declined to 55,000 men while the States Army reached 58,000 in 1627.[34]

The Republic sallies forth (1629–1635)

Meanwhile, the Imperial forces had surged in Germany after the initial setback from the intervention of Christian IV of Denmark in the war in 1625. Both the Danes and Mansfelt were defeated in 1626, and the Catholic League occupied the northern German lands that had hitherto acted as a buffer zone for the Republic. For a while in 1628 an invasion of the eastern part of the Republic seemed imminent. However, the relative might of Spain, the main player up to now in the German civil war, was ebbing fast. By April 1629 the States Army counted 77,000 soldiers, half as much again as the Army of Flanders at that point in time. This allowed Frederick Henry to raise a mobile army of 28,000 (the other troops were used in the fixed garrisons of the Republic) and invest 's-Hertogenbosch. During the siege of this strategic fortress city the imperialist and Spanish allies launched a diversionary attack from Germany's IJssel line. After crossing this river, they invaded the Dutch heartland, getting as far as the city of Amersfoort, which promptly surrendered. The States General, however, mobilised civic militias and scrounged garrison troops from fortresses all around the country, assembling an army that at the height of the emergency numbered no less than 128,000 troops. This enabled Frederick Henry to maintain his siege of 's-Hertogenbosch. When Dutch troops surprised the Spanish fortress of Wesel, which acted as the principal Spanish supply base, this forced the invaders to retreat to the IJssel. 's-Hertogenbosch surrendered in September 1629 to Frederick Henry.[35]

.jpg)

The loss of Wesel and 's-Hertogenbosch (a city that had been fortified according to the most modern standards, often incorporating Dutch innovations in fortification), in short succession, caused a sensation in Europe. It demonstrated that the Dutch, for the moment, enjoyed strategic superiority. 's-Hertogenbosch was the linchpin of the ring of Spanish fortifications in Brabant; its loss left a gaping hole in the Spanish front. Thoroughly shaken, Philip IV now overruled Olivares and offered an unconditional truce. The States General refused to consider this offer until the Imperial forces had left Dutch territory. Only after this had been accomplished did they remit the Spanish offer to the States of the provinces for consideration. The popular debate that followed split the provinces. Friesland, Groningen and Zeeland, predictably, rejected the proposal. Frederick Henry appears to have favoured it personally, but he was hampered by the political divisions in the province of Holland where radical Counter-Remonstrants and moderates were unable to agree. The Counter-Remonstrants urged in guarded terms a final eradication of "Remonstrant" tendencies in the Republic (thus establishing internal "unity") before a truce could even be considered. The radical Calvinist preachers urged a "liberation" of more of the Spanish Netherlands. Shareholders in the WIC dreaded the prospect of a truce in the Americas, which would thwart the plans of that company to stage an invasion of Portuguese Brazil. The peace party and the war party in the States of Holland therefore perfectly balanced each other and deadlock ensued. Nothing was decided during 1629 and 1630.[36]

.jpg)

To break the deadlock in the States of Holland, Frederick Henry planned a sensational offensive in 1631. He intended to invade Flanders and make a deep thrust toward Dunkirk, like his brother had done in 1600. His expedition was even larger. He embarked 30,000 men and 80 field guns on 3,000 rivercraft for his amphibious descent on IJzendijke. From there he penetrated to the Bruges-Ghent canal that the Brussels government had dug to circumvent the Dutch blockade of the coastal waters. Unfortunately, at this stage a sizeable Spanish force appeared to his rear, which caused a row with panicky deputies-in-the-field that, as usual, were micro-managing the campaign for the States General. The civilians prevailed, and a very angry Frederick Henry had to order an ignominious retreat of the Dutch invading force.[37]

Finally, in 1632, Frederick Henry was allowed to deliver his death blow. The initial move in his offensive was to have a reluctant States General publish (over the objections of the radical Calvinists) a proclamation promising that the free exercise of the Catholic religion would be guaranteed in places that the Dutch army would conquer that year. The inhabitants of the Southern Netherlands were invited to "throw off the yoke of the Spaniards." This piece of propaganda would prove to be very effective. Frederick Henry now invaded the Meuse valley with 30,000 troops. He took Venlo, Roermond and Sittard in short order. As promised, the Catholic churches and clergy were left unmolested. Then, on 8 June, he laid siege to Maastricht. A desperate effort of Spanish and Imperialist forces to relieve the city failed and on 20 August 1632, Frederick Henry sprang his mines, breaching the walls of the city. It capitulated three days later. Here also, the Catholic religion was allowed to remain.[38]

The infanta Isabella was now forced to convene the southern States General for the first time since her inauguration in 1598. They met in September (as it turned out for the last time under Spanish rule). Most southern provinces advocated immediate peace talks with the Republic so as to preserve the integrity of the South and the free exercise of the Catholic religion. A "southern" States General delegation met the "northern" States General, represented by its deputies-in-the-field in Maastricht. The "southern" delegates offered to negotiate on the strength of the authorisation given in 1629 by Philip IV. However, Philip and Olivares secretly cancelled this authorisation, as they considered the initiative of the southern States General an "usurpation" of royal power. They never intended to honour any agreement that might ensue.[39]

On the Dutch side, there was the usual disunity. Frederick Henry hoped to achieve a quick result, but Friesland, Groningen and Zeeland opposed the talks outright, while divided Holland dithered. Eventually, those four provinces authorised talks with only the southern provinces, leaving Spain out. Evidently, such an approach would make the resulting agreement worthless, as only Spain possessed any troops. The peace party in the Republic finally brought about meaningful negotiations in December 1632, when valuable time had already been lost, enabling Spain to send reinforcements. Both sides presented demands that were irreconcilable at first, but after much palaver the southern demands were reduced to the evacuation of Portuguese Brazil (which had been invaded by the WIC in 1630) by the Dutch. In return, they offered Breda and an indemnity for the WIC for giving up Brazil. The Dutch (over the opposition of the war party that considered the demands too lenient) reduced its demands to Breda, Geldern, and the Meierij area around 's-Hertogenbosch, in addition to tariff-concessions in the South. Furthermore, as they realised that Spain would never concede Brazil, they proposed to limit the peace to Europe, continuing the war overseas.[40]

By June 1633 the talks were on the verge of collapse. A shift in Dutch politics ensued that would prove fateful for the Republic. Frederick Henry, sensing that the talks were going nowhere, proposed to put an ultimatum to the other side to accept the Dutch demands. However, he lost the support of the "peace party" in Holland, led by Amsterdam. These regents wanted to offer further concessions to gain peace. The peace party gained the upper hand in Holland, for the first time since 1618 standing up to the stadtholder and the Counter-Remonstrants. Frederick Henry, however, managed to gain the support of the majority of the other provinces and those voted on 9 December 1633 (overruling Holland and Overijssel) to break off the talks.[41]

Franco-Dutch Alliance (1635–1640)

While the peace negotiations had been dragging on, events elsewhere in Europe of course had not stood still. While Spain was busy fighting the Mantuan war, the Swedes had intervened in the Thirty Years' War in Germany under Gustavus Adolphus in 1630, supported by French and Dutch subsidies. The Swedes used the new Dutch infantry tactics (enhanced with improved cavalry tactics) with much more success against the Imperialist forces than the German Protestants had done and so gained a number of important successes, turning the tide in the war.[42] However, once its war with Italy ended in 1631, Spain was able to build its forces in the northern theatre of war up to strength again. The Cardinal-Infante brought a strong army up, by way of the Spanish Road, and at the Battle of Nördlingen (1634) this army, combined with Imperialist forces, using the traditional Spanish tercio tactics, decisively defeated the Swedes. He then marched immediately on Brussels, where he succeeded the old Infanta Isabella who had died in December 1633. Spain's strength in the Southern Netherlands was now appreciably enhanced.

.jpg)

The Dutch, now with no prospect of peace with Spain, and faced with a resurgent Spanish force, decided to take the French overtures for an offensive alliance against Spain more seriously. This change in strategic policy was accompanied by a political sea-change within the Republic. The peace party around Amsterdam objected to the clause in the proposed treaty with France that bound the Republic's hands by prohibiting the conclusion of a separate peace with Spain. This would shackle the Republic to French policies and so constrain its independence. The resistance to the French alliance by the moderate regents caused a rupture in the relations with the stadtholder. Henceforth Frederick Henry would be much more closely aligned with the radical Counter-Remonstrants who supported the alliance. This political shift promoted the concentration of power and influence in the Republic in the hands of a small group of the stadtholder's favourites. These were the members of the several secrete besognes (secret committees) to which the States General more and more entrusted the conduct of diplomatic and military affairs. Unfortunately, this shift to secret policy-making by a few trusted courtiers also opened the way for foreign diplomats to influence policy-making with bribes. Some members of the inner circle performed prodigies of corruption. For instance, Cornelis Musch, the griffier (clerk) of the States General received 20,000 livres for his services in pushing the French treaty through from Cardinal Richelieu, while the pliable Grand Pensionary Jacob Cats (who had succeeded Adriaan Pauw, the leader of the opposition against the alliance) received 6,000 livres.[43]

The Treaty of Alliance that was signed in Paris, in February 1635, committed the Republic to invade the Spanish Netherlands simultaneously with France later that year. The treaty previewed a partitioning of the Spanish Netherlands between the two invaders. If the inhabitants would rise against Spain, the Southern Netherlands would be afforded independence on the model of the Cantons of Switzerland, though with the Flemish seacoast, Namur and Thionville annexed by France, and Breda, Geldern and Hulst going to the Republic. If the inhabitants resisted, the country would be partitioned outright, with the Francophone provinces and western Flanders going to France, and the remainder to the Republic. The latter partitioning opened the prospect that Antwerp would be re-united with the Republic, and the Scheldt reopened for trade in that city, something Amsterdam was very much opposed to. The treaty also provided that the Catholic religion would be preserved in its entirety in the provinces to be apportioned to the Republic. This provision was understandable from the French point of view, as the French government had recently suppressed the Huguenots in their strongpoint of La Rochelle (with support of the Republic), and generally was reducing Protestant privileges. It enraged the radical Calvinists in the Republic, however. The treaty was not popular in the Republic for those reasons.[44]

Dividing up the Spanish Netherlands proved more difficult than foreseen. Olivares had drawn up a strategy for this two-front war that proved very effective. Spain went on the defensive against the French forces that invaded in May 1635 and successfully held them at bay. The Cardinal-Infante brought his full offensive forces to bear on the Dutch, however, in hopes of knocking them out of the war in an early stage, after which France would soon come to terms herself, it was hoped. The Army of Flanders now again numbered 70,000 men, at least at parity with the Dutch forces. Once the force of the double invasion by France and the Republic had been broken, these troops emerged from their fortresses and attacked the recently conquered Dutch areas in a pincer movement. In July 1635 Spanish troops from Geldern captured the strategically essential fortress of the Schenkenschans. This was situated on an island in the Rhine near Cleves and dominated the "back door" into the Dutch heartland along the north bank of the river Rhine. Cleves itself was soon captured by a combined Imperialist-Spanish force and Spanish forces overran the Meierij.[45]

The Republic could not let the capture of the Schenkenschans stand. Frederick Henry therefore concentrated a huge force to besiege the fortress even during the winter months of 1635. Spain held tenaciously on to the fortress and its strategic corridor through Cleves. She hoped that the pressure on this strategic point, and the threat of unhindered invasion of Gelderland and Utrecht, would force the Republic to give in. The planned Spanish invasion never materialised, however, as the stadtholder forced the surrender of the Spanish garrison in Schenkenschans in April 1636. This was a severe blow for Spain.[46]

The next year, thanks to the fact that the Cardinal-Infante shifted the focus of his campaign to the French border in that year, Frederick Henry managed to recapture Breda with a relatively small force, at the successful fourth Siege of Breda, (21 July–11 October 1637). This operation, which engaged his forces for a full season, was to be his last success for a long time, as the peace party in the Republic, over his objections, managed to cut war expenditure and shrink the size of the Dutch army. These economies were pushed through despite the fact that the economic situation in the Republic had improved appreciably in the 1630s, following the economic slump of the 1620s caused by the Spanish embargoes. The Spanish river blockade had ended in 1629. The end of the Polish–Swedish War in 1629 ended the disruption of Dutch Baltic trade. The outbreak of the Franco-Spanish War (1635) closed the alternate trade route through France for Flemish exports, forcing the South to pay the heavy Dutch wartime tariffs. Increased German demand for foodstuffs and military supplies[47] as a consequence of military developments in that country, contributed to the economic boom in the Republic, as did successes of the VOC in the Indies and the WIC in the Americas (where the WIC had gained a foothold in Portuguese Brazil after its 1630 invasion, and now conducted a thriving sugar trade). The boom generated much income and savings, but there were few investment possibilities in trade, due to the persisting Spanish trade embargoes. As a consequence, the Republic experienced a number of speculative bubbles in housing, land (the lakes in North Holland were drained during this period) and, notoriously, tulips. Despite this economic upswing, which translated into increased fiscal revenues, the Dutch regents showed little enthusiasm for maintaining the high level of military expenditures of the middle 1630s. The échec of the Battle of Kallo of June 1638 did little to get more support for Frederick Henry's campaigns in the next few years. These proved unsuccessful; his colleague-in-arms Hendrik Casimir, the Frisian stadtholder[48] died in battle during the unsuccessful siege of Hulst in 1640.[49]

However, the Republic gained great victories at other locations. The war with France had closed the Spanish Road for Spain, making it difficult to bring up reinforcements from Italy. Olivares therefore decided to send 20,000 troops by sea from Spain in a large armada. This fleet was destroyed by the Dutch navy under Maarten Tromp and Witte Corneliszoon de With in the Battle of the Downs of 31 October 1639. This left little doubt that the Republic now possessed the strongest navy in the world, also because the Royal Navy was forced to stand by impotently while the battle raged in English territorial waters.[50]

Endgame (1640–1648)

In Asia and the Americas, the war had gone well for the Dutch. Those parts of the war were mainly fought by proxies, especially the Dutch West and East India companies. These companies, under charter from the Republic, possessed quasi-sovereign powers, including the power to make war and conclude treaties on behalf of the Republic. After the invasion of Portuguese Brazil by a WIC amphibious force in 1630, the extent of New Holland, as the colony was called, grew gradually, especially under its governor-general Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, in the period 1637–1644. It stretched from the Amazon river to Fort Maurits on the São Francisco River. Soon a large number of sugar plantations flourished in this area, enabling the company to dominate the European sugar trade. The colony was the base for conquests of Portuguese possessions in Africa also (due to the peculiarities of the trade winds that make it convenient to sail to Africa from Brazil in the Southern Hemisphere). Beginning in 1637 with the conquest of Portuguese Elmina Castle, the WIC gained control of the Gulf of Guinea area on the African coast, and with it of the hub of the slave trade to the Americas. In 1641, a WIC expedition sent from Brazil under command of Cornelis Jol conquered Portuguese Angola. The Spanish island of Curaçao (with important salt production) was conquered in 1634, followed by a number of other Caribbean islands.[51]

The WIC empire in Brazil started to unravel, however, when the Portuguese colonists in its territory started a spontaneous insurrection in 1645. By that time the official war with Portugal was over, as Portugal itself had risen against the Spanish crown in December 1640. The Republic soon concluded a ten-year truce with Portugal, but this was limited to Europe. The overseas war was not affected by it. By the end of 1645 the WIC had effectively lost control of north-east Brazil. There would be temporary reversals after 1648, when the Republic sent a naval expedition, but by then the Eighty Years' War was over.[52]

In the Far East the VOC captured three of the six main Portuguese strongholds in Portuguese Ceylon in the period 1638–41, in alliance with the king of Kandy. In 1641 Portuguese Malacca was conquered. Again, the main conquests of Portuguese territory would follow after the end of the war.[53]

The results of the VOC in the war against the Spanish possessions in the Far East were less impressive. The battles of Playa Honda in the Philippines in 1610, 1617 and 1624 resulted in defeats for the Dutch. An expedition in 1647 under Maarten Gerritsz. de Vries equally ended in a number of defeats in the Battle of Puerto de Cavite and the Battles of La Naval de Manila. However, these expeditions were primarily intended to harass Spanish commerce with China and capture the annual Manila galleon, not (as is often assumed) to invade and conquer the Philippines.[54]

The revolts in Portugal and Catalonia, both in 1640, weakened Spain's position appreciably. Henceforth there would be increasing attempts by Spain to commence peace negotiations. These were initially rebuffed by the stadtholder, who did not wish to endanger the alliance with France. Cornelis Musch, as griffier of the States General, intercepted all correspondence the Brussels government attempted to send to the States on the subject (and was lavishly compensated for these efforts by the French).[55] Frederick Henry also had an internal political motive to deflect the peace feelers, though. The regime, as it had been founded by Maurice after his coup in 1618, depended on the emasculation of Holland as a power center. As long as Holland was divided the stadtholder reigned supreme. Frederick Henry also depended for his supremacy on a divided Holland. At first (up to 1633) he therefore supported the weaker moderates against the Counter-Remonstants in the States of Holland. When the moderates gained the upper hand after 1633, he shifted his stance to support of the Counter-Remonstrants and the war party. This policy of "divide and conquer" enabled him to achieve a monarchical position in all but name in the Republic. He even strengthened it, when after the death of Hendrik Casimir, he deprived the latter's son William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz of the stadtholderates of Groningen and Drenthe in an unseemly intrigue. William Frederick only received the stadtholderate of Friesland and Frederick Henry after 1640 was stadtholder in the other six provinces.[56]

But this position was only secure as long as Holland remained divided. And after 1640 the opposition to the war more and more united Holland. The reason, as often in the Republic's history was money: the Holland regents were less and less inclined, in view of the diminished threat from Spain, to finance the huge military establishment the stadtholder had built up after 1629. Especially as this large army brought disappointing results anyway: in 1641 only Gennep was captured. The next year Amsterdam succeeded in getting a cutback of the army from over 70,00 to 60,000 accepted over the stadtholder's objections.[57]

The Holland regents continued their attempts at whittling down the stadtholder's influence by breaking up the system of secrete besognes in the States General. This helped wrest influence from the stadtholder's favourites, who dominated these committees. It was an important development in the context of the general peace negotiations which the main participants in the Thirty Years' War (France, Sweden, Spain, the Emperor and the Republic) started in 1641 in Münster and Osnabrück. The drafting of the instructions for the Dutch delegation occasioned spirited debate and Holland made sure that she was not barred from their formulation. The Dutch demands that were eventually agreed upon were:

- cession by Spain of the entire Meierij district;

- recognition of Dutch conquests in the Indies (both East and West);

- permanent closure of the Scheldt to Antwerp commerce;

- tariff concessions in the Flemish ports; and

- lifting of the Spanish trade embargoes.[58]

While the peace negotiations were progressing at a snail's pace, Frederick Henry managed a last few military successes: in 1644 he captured Sas van Gent and Hulst in what was to become States Flanders. In 1646, however, Holland, sick of the feet-dragging in the peace negotiations, refused to approve the annual war budget, unless progress was made in the negotiations. Frederick Henry now gave in and began to promote the peace progress, instead of frustrating it. Still, there was so much opposition from other quarters (the partisans of France in the States General, Zeeland, Frederick Henry's son William) that the peace could not be concluded before Frederick Henry's death on 14 March 1647.[59]

Peace of Münster

The negotiations between Spain and the Republic formally started in January 1646 as part of the more general peace negotiations between the warring parties in the Thirty Years' War. The States General sent eight delegates from several of the provinces as none trusted the others to represent them adequately. They were Willem van Ripperda (Overijssel), Frans van Donia (Friesland), Adriaen Clant tot Stedum (Groningen), Adriaen Pauw and Jan van Mathenesse (Holland), Barthold van Gent (Gelderland), Johan de Knuyt (Zeeland), and Godert van Reede (Utrecht). The Spanish delegation was led by Gaspar de Bracamonte, 3rd Count of Peñaranda. The negotiations were held in what is now the Haus der Niederlande in Münster.

The Dutch and Spanish delegations soon reached an agreement, that was based on the text of the Twelve Years' Truce. It therefore confirmed Spain's recognition of Dutch independence. The Dutch demands (closure of the Scheldt, cession of the Meierij, formal cession of Dutch conquests in the Indies and Americas, and lifting of the Spanish embargoes) were generally met. However, the general negotiations between the main parties dragged on, because France kept formulating new demands. Eventually it was decided therefore to split off the peace between the Republic and Spain from the general peace negotiations. This enabled the two parties to conclude what technically was a separate peace (to the annoyance of France that maintained that this contravened the alliance treaty of 1635 with the Republic).

.jpg)

The text (in 79 articles) of the Treaty was fixed on 30 January 1648. It was then sent to the principals (king Philip IV of Spain and the States General) for ratification. Five provinces voted (against the advice of stadtholder William) to ratify on 4 April (Zeeland and Utrecht being opposed). Utrecht finally yielded to pressure by the other provinces but Zeeland held out and refused to sign. It was eventually decided to ratify the peace without Zeeland's consent. The delegates to the peace conference affirmed the peace on oath on 15 May 1648 (though the delegate of Zeeland refused to attend, and the delegate of Utrecht suffered a possibly diplomatic illness).[60]

In the broader context of the treaties between France and the Holy Roman Empire, and Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire of 14 and 24 October 1648, which comprise the Peace of Westphalia, but which were not signed by the Republic, the Republic now also gained formal "independence" from the Holy Roman Empire, just like the Swiss Cantons. In both cases this was just a formalisation of a situation that had already existed for a long time. France and Spain did not conclude a treaty and so remained at war until the peace of the Pyrenees of 1659. The peace was celebrated in the Republic with sumptuous festivities. It was solemnly promulgated on the 80th anniversary of the execution of the Counts of Egmont and Horne on 5 June 1648.

Aftermath

New border between North and South

The Dutch Republic made some limited territorial gains in the Spanish Netherlands but did not succeed in regaining the entire territory lost before 1590. The end result of the war therefore was a permanent split of the Habsburg Netherlands into two parts: the territory of the Republic roughly corresponds with present-day Netherlands and the Spanish Netherlands corresponds approximately with present-day Belgium, Luxembourg and Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Overseas, the Dutch Republic gained, through the intermediary of its two chartered companies, the United East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), important colonial possessions, largely at the expense of Portugal. The peace settlement was part of the comprehensive 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which formally separated the Dutch Republic from the Holy Roman Empire. In the course of the conflict, and as a consequence of its fiscal-military innovations, the Dutch Republic emerged as a Great Power, whereas the Spanish Empire lost its European hegemonic status.

Political situation

Soon after the conclusion of the peace the political system of the Republic entered a crisis. The same forces that had sustained the Oldenbarnevelt regime in Holland, and that had been so thoroughly shattered after Maurice's 1618 coup, had finally coalesced again around what was to become known as the States-Party faction. This faction had slowly been gaining prominence during the 1640s until they had forced Frederick Henry to support the peace. And now they wanted their peace dividend. The new stadtholder, William II, on the other hand, far less adept as a politician than his father, hoped to continue the predominance of the stadtholderate and the Orangist faction (mostly the aristocracy and the Counter-Remonstrant regents) as in the years before 1640. Above all, he wanted to maintain the large wartime military establishment, even though the peace made that superfluous. The two points of view were irreconcilable. When the States-Party regents started to cut down the size of the standing army to a peace-time complement of about 30,000, a struggle for power in the Republic ensued. In 1650 stadtholder William II finally followed the path of his uncle Maurice and seized power in a coup d'état, but he died a few months later from smallpox. The power-vacuum which followed was quickly filled by the States-Party regents, who founded their new republican regime that has become known as the First Stadtholderless Period.[61]

Dutch trade on the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean exploded in the decade after the peace, as did trade in general, because trade patterns in all European areas were so tightly interlocked via the hub of the Amsterdam Entrepôt. Dutch trade in this period reached its pinnacle; it came to completely dominate that of competing powers, like England, that had only a few years previously profited greatly from the handicap the Spanish embargoes posed to the Dutch. Now the greater efficiency of Dutch shipping had a chance to be fully translated into shipping prices, and the competitors were left in the dust. The structure of European trade therefore changed fundamentally in a way that was advantageous to Dutch trade, agriculture and industry. One could truly speak of Dutch primacy in world trade. This not only caused a significant boom for the Dutch economy, but also much resentment in neighbouring countries, like first the Commonwealth of England and later France. Soon, the Republic was embroiled in military conflicts with these countries, which culminated in their joint attack on the Republic in 1672. They almost succeeded in destroying the Republic in that year, but the Republic rose from its ashes and by the turn of the century, she was one of the two European power centres, together with the France of Louis XIV of France.[62]

Portugal was no party in the peace and the war overseas between the Republic and that country resumed fiercely after the expiration of the ten-year truce of 1640. In Brazil and Africa the Portuguese managed to reconquer most of the territory lost to the WIC in the early 1640s after a long struggle. However, this occasioned a short war in Europe in the years 1657–60, during which the VOC completed its conquests in Ceylon and the coastal areas of the Indian subcontinent. Portugal was forced to indemnify the WIC for its losses in Brazil.[63]

Psychological impact

The success of the Dutch Republic in its struggle to get away from the Spanish Crown had damaged Spain's Reputación, a concept that, according to Olivares' biographer J.H. Elliot,[64] strongly motivated that statesman. In the minds of Spaniards the land of Flanders became linked to war. The idea of a second Flanders –a place of "endless war, suffering and death"– haunted the Spanish for many years after the war ended. In the 16th and 17th centuries the concept of a second (or "another") Flanders was variously used while referring to the 1591 situation in Aragón, the Catalan Revolt and the 1673 rebellion in Messina. Jesuit father Diego de Rosales described Chile from a military point of view as "Indian Flanders" (Flandes indiano), a phrase that was later adopted by historian Gabriel Guarda.[65]

Maps of the shifting front of the war

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

|

|

- Battles of La Naval de Manila

- Battles of the Eighty Years' War

- Bioko

- Colonial Brazil

- Council of Troubles

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Ceylon

- Dutch East Indies

- Dutch Formosa

- Dutch India

- Dutch Malacca

- European wars of religion

- Martyrs of Gorkum

- Portuguese Ceylon

- Portuguese Empire

- Portuguese India

- Portuguese Malacca

- Saint Martin

- Spanish Formosa

- Spanish Road

- Union of Delft

References

- ↑ Clodfelter, M. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. p. 17.

- ↑ The Dutch States General, for dramatic effect, decided to promulgate the ratification of the Peace of Münster (which was actually ratified by them on 15 May 1648) on the 80th anniversary of the execution of the Counts of Egmont and Horne, 5 June 1648. See Maanen, H. van (2002), Encyclopedie van misvattingen, Boom, p. 68. ISBN 90-5352-834-2.

- ↑ Jonathan Israel, The Dutch Republic: its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806 (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995), pp. 159-160.

- ↑ They formed the Burgundian Circle that under the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 was to be transferred as a unit in hereditary succession in the House of Habsburg.

- ↑ Cf. Koenigsberger, pp. 184–192

- ↑ Motley, John Lothrop (1885). The Rise of the Dutch Republic. vol. I. Harper Brothers.

As Philip was proceeding on board the ship which was to bear him forever from the Netherlands, his eyes lighted upon the Prince. His displeasure could no longer be restrained. With angry face he turned upon him, and bitterly reproached him for having thwarted all his plans by means of his secret intrigues. William replied with humility that every thing which had taken place had been done through the regular and natural movements of the states. Upon this the King, boiling with rage, seized the Prince by the wrist, and shaking it violently, exclaimed in Spanish, "No los estados, ma vos, vos, vos!—Not the estates, but you, you, you!" repeating thrice the word vos, which is as disrespectful and uncourteous in Spanish as "toi" in French.

- ↑ Tracy, p. 66

- ↑ Tracy, p. 68

- ↑ Tracy, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Tracy, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 399–405

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 458–9

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 407–8

- ↑ Frederick was the son of Maurice's half-sister Countess Louise Juliana of Nassau

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 465–9

- ↑ The Duke of Lerma had been replaced by his son in 1618

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 469–71

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 471

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 472–3

- ↑ Under the terms of the Will of Philip II the pretended sovereignty over the Netherlands now reverted to Philip III.

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 473–4

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 3–7

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 8–10

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 11–15

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 21–2

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 15–8

- ↑ Israel, pp. 20–1

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 23–4

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 25–27

- ↑ Israel (1990), pp. 32–33

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 480–1

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 479–480, 483–484

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 485–96

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 497–9

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 506–7

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 508–13

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 513

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 515–6

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 517

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 518–9

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 521–3

- ↑ Glete, pp. 204, 208

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 523–7

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 527–8

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 528–9

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 529–30

- ↑ The Republic functioned as the main arsenal for the Protestant forces during the Thirty Years' War; Puype, P.J., Hoeven, M. van der (1996) The Arsenal of the World: The Dutch Arms Trade in the Seventeenth Century, Batavian Lion International, ISBN 90-6707-413-6

- ↑ Hendrik Casimir succeeded his father Ernst Casimir as stadtholder of Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe in 1632.

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 530–6

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 537

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 934

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 935

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 936

- ↑ Cf. Roessingh, M. (1968) "Nederlandse betrekkingen met de Philippijnen", in: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-, en Volkenkunde, jrg. 124, no. 3, pp. 482–504

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 540

- ↑ Israel (1995) pp. 538–9

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 541

- ↑ Israel (1995), p. 542

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 544–6

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 596–7

- ↑ Israel (1995), pp. 597–609

- ↑ Israel (1989), pp. 197–292

- ↑ Israel (1989), pp. 248–50

- ↑ Elliot, J.H. (1986) The Count-Duke of Olivares. The Statesman in an Age of Decline. Yale University: New Haven and London

- ↑ Baraibar, Alvaro (2013). "Chile como un "Flandes indiano" en las crónicas de los siglos VI y VII". Revista Chilena de Literatura (in Spanish). 85. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

Sources

- Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur (in Spanish). Santiago: Catalonia. ISBN 956-8303-02-2.

- Gelderen, M. van (2002), The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555–1590, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-89163-9

- Glete, J. (2002),War and the State in Early Modern Europe. Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500–1660, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-22645-7

- Israel, Jonathan (1989), Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-821139-2

- Israel, Jonathan (1990), Empires and Entrepôts: The Dutch, the Spanish Monarchy, and the Jews, 1585–1713, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 1-85285-022-1

- Israel, Jonathan (1995), The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806, Clarendon Press, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-873072-1

- Koenigsberger, H.G. (2007) [2001], Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-04437-0

- Parker, G. (2004) The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659. Second edition. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-54392-7 paperback

- Tracy, J.D. (2008), The Founding of the Dutch Republic: War, Finance, and Politics in Holland 1572–1588, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-920911-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eighty Years' War. |

- (in Dutch) De Bello Belgico

- (in Dutch) Correspondence of William of Orange

- (in Spanish) La Guerra de Flandes, desde la muerte del emperador Carlos V hasta la Tregua de los Doce Años

- (in Dutch) "Nederlandse Opstand" on www.onsverleden.net