Barbary lion

| Barbary lion | |

|---|---|

| |

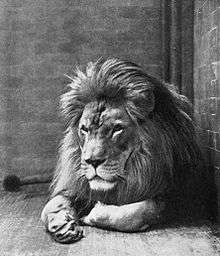

| A male Barbary lion photographed in Algeria by Alfred Edward Pease in 1893.[1] | |

_(18427026972).jpg) | |

| Lioness and cubs, New York Zoo, 1903. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo |

| Subspecies: | P. l. leo |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Panthera leo barbaricus (Meyer, 1826) | |

The Barbary lion is considered a population of the African lion subspecies Panthera leo leo. This population is regionally extinct in North Africa.[2] It inhabited the Atlas Mountains and was therefore also known as the Atlas lion.[3] Alfred Edward Pease referred to the Barbary lion as the North African lion and claimed that the population had diminished since the mid-19th century, following the diffusion of firearms and bounties for shooting them.[1] The last recorded shooting of a wild Barbary lion took place in Morocco, near Tizi n'Tichka in 1942. Small groups of lions may have survived in Algeria until the early 1960s, and in Morocco until the mid-1960s.[4]

Results of morphological and genetic analyses of lions warrant the designation of African lion subpopulations in the northern, western and central regions (the latter having been grouped under P. l. senegalensis)[5] into a single subspecies, that is P. l. leo, separate from P. l. melanochaita.[6][7]

Taxonomy

A lion from Constantine, Algeria was considered the type specimen of the specific name Felis leo used by Linnaeus in 1758.[8][9] The Barbary lion was first described by the Austrian zoologist Johann Nepomuk Meyer under the trinomen Felis leo barbaricus on the basis of a type specimen from the Barbary Coast.[10]

While the historical Barbary lion was morphologically distinct, its genetic uniqueness remains questionable; still unclear is the taxonomic status of surviving lions frequently considered as Barbary lions, including those that originated from the collection of the King of Morocco.[11]

In a comprehensive study about the evolution of lions, 357 samples of wild and captive lions from African countries and India were examined. Results indicate that four captive lions from Morocco did not exhibit any unique genetic characteristics, but shared mitochondrial haplotypes H5 and H6 with lions from West and Central Africa. They were all part of a major mtDNA grouping that also included Asiatic lion samples. Results provide evidence for the hypothesis that this group called 'lineage III' developed in East Africa, and about 118,000 years ago travelled north and west in the first wave of lion expansions. It broke up into haplotypes H5 and H6 within Africa, and then into H7 and H8 in Western Asia. African lions probably constitute a single population that interbred during several waves of migration since the Late Pleistocene.[6]

Genetic samples from lions in eastern and southern Africa were quite similar.[5] Captive lions from the Addis Ababa Zoo in Ethiopia were genetically examined and compared with six wild lion populations. Results showed that they are distinct in phenotype and mitochondrial DNA.[12]

In 2017, the lion populations in Northern, Western and Central Africa and Asia were subsumed under P. l. leo.[13]

Characteristics

In some historic accounts, the weights of wild males was indicated as being very heavy, and reaching 270 to 300 kg (600 to 660 lb). But the accuracy of the measurements is questionable, and the sample size of captive Barbary lions was too small to conclude that it was the biggest lion subspecies.[14] Nevertheless, the Gettysburg Compiler (1899) described a lion called 'Atlas', from the Atlas Mountains between Algeria and Morocco, as being "much superior to the black-maned lions of South Africa in bulk and bravery."[15]

Head-to-tail length of stuffed males in zoological collections varies from 2.35 to 2.8 m (7 ft 9 in to 9 ft 2 in), and females measure around 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in). A 19th-century hunter described a large male allegedly measuring 3.25 m (10.7 ft), including a 75 cm (30 in) long tail. Male Barbary lions were described as having very dark and long-haired manes that extended over the shoulder and to the belly.[16][17]

Lion manes

Besides Cape lions, lions in Northwestern Africa were said to have "the most luxuriant and extensive manes" amongst lions, with "tresses on flanks and abdomen". In contrast, lions in Egypt appeared to have had less developed manes, like those in the Arabian peninsula and east coast of the Mediterranean Sea.[18] Lions in Mesopotamia also had underbelly hair.[19]

Before it became possible to investigate the genetic diversity of lion populations, the colour and size of lions' manes was thought to be a sufficiently distinct morphological characteristic to accord a subspecific status to populations.[20] Results of a long-term study of Masai lions in Serengeti National Park indicate that various factors, such as ambient temperature, nutrition and the level of testosterone, influence the colour and size of lion manes.[21][5] Sub-Saharan African lions kept in cool environments of European and North American zoos usually develop bigger manes than their wild counterparts. Consequently, Barbary lions may have developed long-haired manes, because of temperatures in the Atlas Mountains that are much lower than in other African regions, particularly in winter.[14] Therefore the size of manes is not regarded as an appropriate evidence for identifying Barbary lions' ancestry. Instead, results of mitochondrial DNA research published in 2006 support the genetic distinctness of Barbary lions in a unique haplotype found in museum specimens that is thought to be of Barbary lion descent. The presence of this haplotype is considered a reliable molecular marker for the identification of Barbary lions surviving in captivity.[20]

Behaviour and ecology

Pease accounted in 1913 that in areas where lions were not very numerous, they were more frequently found in pairs or family parties comprising a lion, lioness and one or two cubs. He several times came across two old lions and a lioness living and hunting together.[1] Observations of wild Barbary lions made between 1839 and 1942 involved solitary animals, pairs and family units. Analysis of these historical records suggests that Barbary lions retained living in prides even when under increasing persecution during the last decades, especially in the eastern Maghreb. The size of prides was likely similar to prides living in sub-Saharan habitats, whereas the density of the Barbary lion population is considered to have been lower than in moister habitats.[4]

When Barbary stags and gazelles became scarce in the Atlas Mountains, lions preyed on herds of livestock that were rather carefully tended.[22] They also preyed on wild boar and red deer.[23]

Sympatric predators included the African leopard and brown bear.[24][25]

Extinction in the wild

The Romans used Barbary lions in the Colosseum to battle with gladiators.[26]

Barbary lions inhabited the range countries of the Atlas Mountains including the Barbary Coast.[17] Jardine remarked in 1834 that at the time lions may have already been eliminated from the coastlines, marking the border to human settlements.[27] In Algeria, they lived in the forest-clad hills and mountains between Ouarsenis in the west, the Pic de Taza in the east, and the plains of the Chelif River in the north. There were also many lions among the forests and wooded hills of the Constantine Province eastwards into Tunisia and south into the Aurès Mountains. By the middle of the 19th century, their numbers had been greatly diminished. The cedar forests of Chelia and neighbouring mountains harboured lions until about 1884.[1] The last survivors in Tunisia were extirpated by 1890.[28]

In the 1970s, Barbary lions were assumed to have been extirpated in the wild in the early 20th century.[17] However, a comprehensive review of hunting and sighting records indicates that a lion was shot in the Moroccan part of the Atlas Mountains in 1942. Additionally, lions were sighted in Morocco and Algeria into the 1950s, and small remnant populations may have survived into the early 1960s, in remote areas.[4]

Conservation

In captivity

_(18243500220).jpg)

Historically, Barbary lions were offered in lieu of taxes and as gifts to royal families of Morocco and Ethiopia. The rulers of Morocco kept these 'royal lions' through war and insurrection, splitting the collection between zoos when the royal family went briefly into exile. After a respiratory disease nearly wiped out the royal lions in the late 1960s, the current ruler established enclosures in Temara near Rabat, Morocco, to house the lions and improve their quality of life. There are currently a small number of 'royal lions' that have the pedigree and physical characteristics to be considered as mostly pure Barbary descendants. Some were returned to the palace when the exiled ruler returned to the throne.[14]

In the 19th century and the early 20th century, Barbary lions were often kept in hotels and circus menageries. The lions in the Tower of London were transferred to more humane conditions at the London Zoo in 1835 on the orders of the Duke of Wellington. One famous Barbary lion named "Sultan" was kept in the London Zoo in 1896.[29]

Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia had a collection of lions at Addis Abeba's zoo. They looked like Barbary or Cape lions, because of their dark, brown manes that extended over the chest through the front legs.[30]

In 2011, the Port Lympne Animal Park in Kent received a Barbary lioness as a mate for the resident male.[31]

More recently a number of researchers and zoos have supported the development of a studbook of lions directly descended from the King of Morocco's collection.[11] This work has been conducted on the precautionary principle that this subpopulation of animals may hold unique Barbary lion genes as well as demonstrating the morphology of the ancestral Barbary lion.

As of June 2016, Wisconsin Big Cat Rescue in Rock Springs, Wisconsin, has two female lions born in 2001 that have been shown by DNA testing to be Atlas lions. The Living Treasures Wild Animal Park in New Castle, Pennsylvania, claims to keep a pair of Barbary lions in the park's collection.[32] The Zoo des Sables d'Olonne, Vendee, France, also claims to have a male and female Atlas lion.[33]

Research

)_(18160964071).jpg)

In the Middle Ages, the lions kept in the menagerie at the Tower of London were Barbary lions, as shown by DNA testing on two well-preserved skulls excavated at the Tower in 1936-1937. The skulls were radiocarbon-dated to 1280-1385 AD and 1420-1480 AD. The growth of civilizations along the Nile and in the Sinai Peninsula by the beginning of the second millennium BC stopped genetic flow by isolating lion populations. Desertification also prevented the Barbary lions from mixing with lions located further south in the continent.[35]

Five tested samples of lions from the famous collection of the King of Morocco are not maternally Barbary lions. Nonetheless, genes of the Barbary lion are likely to be present in common European zoo lions, since this was one of the most frequently introduced subspecies. Therefore, many lions in European and American zoos, which are managed without subspecies classification, are in fact partly descendants of Barbary lions.[20]

In 2006, mtDNA research revealed that a lion specimen kept in the German Neuwied Zoo originated from the collection of the King of Morocco and is very likely a descendant of a Barbary lion.[3]

The former popularity of the Barbary lion as a zoo animal provides the only hope to ever see it again in the wild. Many zoos provide mating programmes. After years of research into the science of the Barbary lion and stories of surviving examples, WildLink International, in collaboration with Oxford University, launched its ambitious International Barbary Lion Project. Oxford used DNA techniques to identify the DNA 'fingerprint' of the Barbary lion subspecies. Researchers took bone samples from remains of Barbary lions in museums across Europe. These samples were returned to Oxford University, where the science team extracted the DNA sequence to identify the Barbary as a separate subspecies.

Although the North African lion is certainly extinct in the wild, WildLink International looked to identify a handful of lions in captivity around the world that may be descended from the original Barbary lion. These descendants were to be tested against the DNA fingerprint, and the degree of any hybridization (from crossbreeding) could then be determined. The best candidates were to then enter a selective breeding programme slated to 'breed back' the Barbary lion. The final phase of the project intended to see the lions released into a national park in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. In March 2010, two lion cubs were moved to The Texas Zoo in Victoria, Texas, where efforts were made to preserve the species under the WildLink International conservation programme. Whether the cubs are of Barbary lion descent is not yet determined.[36]

Cultural significance

- Barbary lions from Mauritania and Numidia were used in Roman Gladiatorial games.[23][24]

- Omar Mukhtar the Libyan revolutionary was called the "Asad aṣ-Ṣaḥrā’" (Arabic: أَسَـد الـصَّـحْـرَاء, "Lion of the Desert").[38]

See also

- Barbary lion versus Siberian tiger

- Barbary Stag

- European lion

- Ex-situ conservation

- Gaetulian lion

- Numidia

- Panthera toscana

- Upper Pleistocene Eurasian cave lion

References

- 1 2 3 4 Pease, A. E. (1913). The Book of the Lion John Murray, London.

- ↑ Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-1. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 Burger, J.; Hemmer, H. (2006). "Urgent call for further breeding of the relic zoo population of the critically endangered Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo Linnaeus 1758)" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 52 (1): 54–58. doi:10.1007/s10344-005-0009-z.

- 1 2 3 Black, S. A.; Fellous, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Roberts, D. L. (2013). "Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation". PLoS ONE. 8 (4): e60174. PMC 3616087

. PMID 23573239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174.

. PMID 23573239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174. - 1 2 3 Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Antunes, A., Troyer, J. L., Roelke, M. E., Pecon-Slattery, J., Packer, C., Winterbach, C., Winterbach, H., Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLoS Genetics. 4 (11): e1000251. PMC 2572142

. PMID 18989457. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251.

. PMID 18989457. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. - ↑ Henschel, P.; Bauer, H.; Sogbohoussou, E. & Nowell, K. (2015). "Panthera leo (West Africa subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-1. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Allen, J. A. (1922–1925). Carnivora Collected by the American Museum Congo Expedition. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. XLVII: 74–281.

- ↑ Harper, F. (1945). Extinct and vanishing mammals of the Old World. American Committee for International Wild Life Protection, New York.

- ↑ Meyer, J. N. (1826). Dissertatio inauguralis anatomico-medica de genere felium. Doctoral thesis, University of Vienna.

- 1 2 Black, S., Yamaguchi, N., Harland, A., Groombridge, J. (2010). "Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 56 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1007/s10344-009-0280-5.

- ↑ Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). "A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5.

- ↑ Kitchener, A.C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Eizirik, E., Gentry, A., Werdelin, L., Wilting, A. and Yamaguchi, N. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 76.

- 1 2 3 Yamaguchi, N., Haddane, B. (2002). The North African Barbary Lion and the Atlas Lion Project. International Zoo News 49/8: 465–481.

- ↑ "Lion against tiger". Gettysburg Compiler. 7 February 1899. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ↑ Mazák, V. (1970). "The Barbary lion, Panthera leo leo, (Linnaeus, 1758): some systematic notes, and an interim list of the specimens preserved in European museums". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 35: 34–45.

- 1 2 3 Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae). Teil III: Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung München (17): 167–280.

- ↑ Heptner, V. G., Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 83–95.

- ↑ Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An Extinct Mesopotamian Lion Subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- 1 2 3 Barnett, R., Yamaguchi, N., Barnes, I., Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7: 507–514. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-24.

- ↑ West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2002). "Sexual selection, temperature, and the lion's mane". Science. 297 (5585): 1339–1343. PMID 12193785. doi:10.1126/science.1073257.

- ↑ Johnston, H. H. (1899). "The lion in Tunisia". In Bryden, H. A. Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 562–564.

- 1 2 Pease, A. E. (1899). "The lion in Algeria". In Bryden, H. A. Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 564–568.

- 1 2 3 Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. ISBN 2-8317-0045-0.

- ↑ Johnston, H. H. (1899). "African bear". In Bryden, H. A. Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 607–608.

- ↑ Patterson, B. D. (2004). The lions of Tsavo: exploring the legacy of Africa's notorious man-eaters. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-07-136333-4.

- ↑ Jardine, W. (1834). The Naturalist's Library. Mammalia Vol. II: the Natural History of Felinae. W. H. Lizars, Edinburgh.

- ↑ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1961). Simba: the life of the lion. Howard Timmins, Cape Town.

- ↑ Edwards, J. (1996). London Zoo from Old Photographs 1852–1914. John Edwards, London.

- ↑ Tefera, M. (2003). Phenotypic and reproductive characteristics of lions (Panthera leo) at Addis Ababa Zoo. Biodiversity & Conservation 12(8): 1629–1639.

- ↑ BBC (2011). Breeding hopes for Barbary lions at Port Lympne. BBC News.

- ↑ Living Treasures Wild Animal Park (2011). .

- ↑ Administrator. "Atlas Lion". zoodessables.fr.

- ↑ Chambers, Delaney (29 January 2017). "150-year-old Diorama Surprises Scientists With Human Remains". news.nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ Barnett R., Yamaguchi N., Shapiro B., Sabin R. (2008). "Ancient DNA analysis indicates the first English lions originated from North Africa". Contributions to Zoology. 77 (1): 7–16.

- ↑ Prince, A. (2010). Austin Zoo Says Goodbye to Lion Cubs Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Austin Zoo and Animal Sanctuary, Austin.

- ↑ Millar, Fergus (2006). A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius II (408–450). University of California Press. p. 279. ISBN 0520941411.

- ↑ as-Salab, Ali Muhammad (2011). Omar Al Mokhtar Lion of the Desert (The Biography of Shaikh Omar Al Mukhtar). Al-Firdous. p. 1. ISBN 978-1874263647.

External links

-

Data related to Panthera leo leo at Wikispecies

Data related to Panthera leo leo at Wikispecies - Being Lion: Barbary Lion Information

- The Sixth Extinction Website: Barbary Lion - Panthera leo leo