Egyptian National Railways

| |

| Reporting mark | ENR |

|---|---|

| Locale | Egypt |

| Dates of operation | 1854–present |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

| Length | 5,083 km (3,158 mi)[1] |

| Headquarters | Cairo |

| Website | Egyptian National Railways |

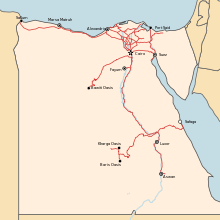

(interactive version)

1435mm gauge track

Egyptian National Railways (ENR; Arabic: السكك الحديدية المصرية Al-Sikak al-Ḥadīdiyyah al-Miṣriyyah) is the national railway of Egypt and managed by the parastatal Egyptian Railway Authority (ERA; Arabic: الهيئة القومية لسكك حديد مصر Al-Haī'ah al-Qawmiyya li-Sikak Ḥadīd Miṣr, literally, "National Agency for Egypt's Railways").

History

1833–77

In 1833 Muhammad Ali Pasha considered building a railway between Suez and Cairo to improve transit between Europe and India. Muhammad Ali had proceeded to buy the rail when the project was abandoned due to pressure by the French who had an interest in building a canal instead.

In 1848 Muhammad Ali died, and in 1851 his successor Abbas I contracted Robert Stephenson to build Egypt's first standard gauge railway. The first section, between Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast and Kafr el-Zayyat on the Rosetta branch of the Nile was opened in 1854.[2] This was the first railway in the Ottoman Empire as well as Africa and the Middle East.[3] In the same year Abbas died and was succeeded by Sa'id Pasha, in whose reign the section between Kafr el-Zayyat and Cairo was completed in 1856 followed by an extension from Cairo to Suez in 1858.[2] This completed the first modern transport link between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, as Ferdinand de Lesseps did not complete the Suez Canal until 1869.

At Kafr el-Zayyat the line between Cairo and Alexandria originally crossed the Nile with an 80 feet (24 m) car float.[4] However, on 15 May 1858 a special train conveying Sa'id's heir presumptive Ahmad Rifaat Pasha fell off the float into the river and the prince was drowned.[4] Stephenson therefore replaced the car float with a swing bridge nearly 500 metres (1,600 ft) long.[4] By the end of Sa'id's reign branches had been completed from Banha to Zagazig on the Damietta branch of the Nile in 1860, to Mit Bera in 1861 and from Tanta to Talkha further down the Damietta Nile in 1863.[2]

Sa'id's successor Isma'il Pasha strove to modernise Egypt and added momentum to railway development. In 1865 a new branch reached Desouk on the Rosetta Nile and a second route between Cairo and Talkha was opened, giving a more direct link between Cairo and Zagazig.[2] The following year a branch southwards from Tanta reached Shibin El Kom.[2] The network started to push southwards along the west side of the Nile with the opening of the line between Imbaba near Cairo and Minya in 1867.[5] A short branch to Faiyum was added in 1868.[5] A line between Zagazig and Suez via Nifisha was completed in the same year.[2] The following year the line to Talkha was extended to Damietta on the Mediterranean coast and a branch opened to Salhiya and Sama'ana.[2]

Imbaba had no rail bridge across the Nile to Cairo until 1891.[4] However, a long line between there and a junction west of Kafr el-Zayyat opened in 1872, linking Imbaba with the national network.[2] From Minya the line southwards made slower progress, reaching Mallawi in 1870 and Assiut in 1874.[5] On the west bank till Najee Hammady from which goes on east bank of the Nile till Aswan. A shorter line southwards linked Cairo with Tura in 1872 and was extended to Helwan in 1875.[2] In the Nile Delta the same year a short branch reached Kafr el-Sheikh and in 1876 a line along the Mediterranean coast linking the termini at Alexandra and Rosetta was completed.[2]

1877–88

By 1877 Egypt had a network of key main lines and the Nile Delta had quite a network, but with this and other development investments, Isma'il had gotten the country deeply into debt. For its first 25 years of operation Egypt's national railway had never even produced an annual report.[6] A Council of Administration with Egyptian, British and French members was appointed in 1877 to put the railway's affairs in order. They published its first annual report in 1879,[6] and in the same year, the British Government had Isma'il Pasha deposed, exiled and replaced with his son Tewfik Pasha. In 1882, the British essentially invaded and occupied Egypt.

With these developments, the Egyptian Railway Administration's rail network stagnated until 1888, but it also put its management in much better order.[6] In 1883 the ERA appointed Frederick Harvey Trevithick, nephew of Francis Trevithick, as Chief Mechanical Engineer.[7] Trevithick found a heterogeneous fleet of up to 246 steam locomotives of many different designs from very different builders in England, Scotland, France and the USA.[7] This lack of standardisation of locomotives or components complicated both locomotive maintenance and general railway operation.[7]

From 1877 to 1888 the ERA struggled to keep up with even basic maintenance[6] but by 1887 Trevithick managed to start a programme to renew 85 of the very mixed fleet of locomotives with new boilers, cylinders and motion.[7] The others he started to replace with four standard locomotive types introduced from 1889 onwards: one class of 0-6-0 for freight, one class of 2-4-0 for mixed traffic, one 0-6-0T tank locomotive for shunting and one class of only ten 2-2-2 locomotives for express passenger trains.[7] Trevithick ensured that these four classes shared as many common components as possible, which simplified maintenance and reduced costs still further.[7]

1888–1914

.jpg)

By 1888 the ERA was in better order and could resume expanding its network. In 1890 a second line between Cairo and Tura opened.[2] On 15 May 1892 the Imbaba Bridge was built across the Nile, linking Cairo with the line south following the west bank of the river.[4] The civil engineer for the bridge was Gustave Eiffel. (It was reformed and renewed in 1924 which is still the only railway bridge across the Nile in Cairo.) Cairo's main Misr Station was rebuilt in 1892. The line south was extended further upriver from Assiut reaching Girga in 1892, Nag Hammadi in 1896, Qena in 1897 and Luxor and Aswan in 1898.[5] With the railroad's completion, construction began the same year on the first Aswan Dam and the Assiut Barrage, main elements of a plan initiated in 1890 by the government[8] to modernize and more fully develop Egypt's existing irrigated agriculture, export potential, and ability to repay debts to European creditors.[9]

In the north in 1891 a link line was opened between Damanhur and Desouk.[2] The line to Shibin El Kom was extended south to Minuf in the same year and reached Ashum in 1896.[2] By then a line across the Nile Delta from a junction north of Talkha on the line to Damietta had reached Biyala.[2] By 1898 this reached Kafr el-Sheikh, completing a more direct route between Damietta and Alexandria.[2] An important extension along the west bank of the Suez Canal linking Nifisha with Ismaïlia, Al Qantarah West and Port Said was completed in 1904.[2] Thereafter network expansion was slower but two short link lines north of Cairo were completed in 1911 followed by a link between Zagazig and Zifta in 1914.[2]

Sinai

The first El Ferdan Railway Bridge over the Suez Canal was completed in April 1918 for the Palestine Military Railway.[4] It was considered a hindrance to shipping so after the First World War it was removed.[4] During the Second World War a steel swing bridge was built in 1942 but this was damaged by a steamship and removed in 1947.[4] A double swing bridge was completed in 1954 but the 1956 Israeli invasion of Sinai severed rail traffic across the canal for a third time.[4] A replacement bridge was completed in 1963[10] but destroyed in the Six-Day War in 1967. A new double swing bridge was completed in 2001 and is the largest swing bridge in the World.[10]

The Palestine Railways main line linked Al Qantarah East with Palestine and Lebanon. It was built in three phases during the First and Second World Wars. Commenced in 1916, it was extended to Rafah on the border with Palestine as part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's Sinai and Palestine Campaign against the Ottoman Empire. The route was extended through to Haifa in Mandate Palestine after World War I, to Tripoli, Lebanon in 1942 and became a vital part of the wartime supply route for Egypt.

As a result of the 1946–48 Israeli War of Independence and subsequent 1948 Arab-Israeli War the Palestine Railways main line was severed at the 1949 Armistice Line. The 1956 Israeli invasion severed Sinai's rail link with the rest of Egypt was reconnected its rail link with Israel. Israel captured a 4211 class 0-6-0 diesel shunting locomotive and five 545 class 2-6-0 steam locomotives.[11] Israel also captured rolling stock including a six-wheel coach dating from 1893 and a 30-ton steam crane built in 1950, both of which Israel Railways then appropriated into its breakdown fleet.[12] Before being forced to withdraw from Sinai in March 1957, Israel systematically destroyed infrastructure including the railway.[13] By 1963 the railway in Sinai was reconnected to the rest of Egypt but remained disconnected from Israel.

In the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel captured more Egyptian railway equipment including one EMD G8, four EMD G12 and three EMD G16 diesel locomotives[14] all of which were appropriated into Israel Railways stock. After 1967 Israel again destroyed the railway across occupied Sinai and this time used the materials in the construction of the Bar Lev Line of fortifications along the Suez Canal.

After numerous years' service on Israel Railways the 30-ton crane, 1893 Belgian 6-wheel coach and one of the EMD G16 diesels are all preserved in the Israel Railway Museum in Haifa.[12]

Museum

Egypt's railway museum was built in 1932 next to Misr Station (now Ramses Station) in Cairo.[5][15] The museum opened in January 1933 to mark the city's hosting of the International Railway Congress.[5][15] Its stock of over 700 items[15] includes models, historic drawings and photographs.[5] Among its most prominent exhibits are three preserved steam locomotives:

- 2-4-2 no. 30, built by Robert Stephenson and Company in 1862[16]

- 0-6-0 no. 986 (originally 189, then 142), built by Robert Stephenson and Company in 1861[16]

- 4-4-2 no. 194 (originally 678) built by the North British Locomotive Company in 1905[16]

Operations

In 2005 ENR operated 5,063 kilometres (3,146 mi) of standard gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) track. Most of the rail system is focused on the Nile delta with lines essentially fanning out from Cairo. In addition, there is a line to the west along the coast that eventually could link to Libya as it did during World War II. From Cairo goes a major line south along the east bank of the Nile to Aswan (Sellel) in Upper Egypt. Neighboring Israel uses the same standard gauge but has been disconnected since 1948.[17] In the South the railway system of Sudan operates on a narrow gauge and is reached after using the ferry past the Aswan dam. Rail service is a critical part of the transportation infrastructure of Egypt but of limited service for transit. 63 kilometres (39 mi) of the network is electrified, namely commuter lines between Cairo-Helwan and Cairo-Heliopolis.[17]

ENR buys locomotives and rail abroad but passenger coaches are built and refurbished in Egypt by the Société Générale Egyptienne de Matériel de Chemins de Fer (SEMAF).[18]

Cargo volume transported by ENR is about 12 million tons annually.[18]

Services were severely disrupted during the political protests in early 2011; operating hours of the Cairo Metro were shortened to comply with the curfew.[19]

On January 16, 2015 Egyptian National Railways signed a €100 million contract with Alstom to supply signalling equipment for the 240 km Beni Suef-Asyut line and maintain services for five years. Also, Alstom will provide smartlock electronic interlocking system to replace the existing electromechanical system, which in turn will increase the number of trains that operate on the route by more than 80%.[20][21]

Passenger trains

ER is the backbone of passenger transportation in Egypt with 800 million passenger miles annually.[18] Air-conditioned passenger trains usually have 1st and 2nd class service, while non-airconditioned trains have 2nd and 3rd class. Most of the network connects the densely populated area of the Nile delta with Cairo and Alexandria as hubs. Train fares in commuter trains and 3rd class passenger trains are kept low as a social service.

There are large volumes of tourist traffic during Eid; this causes problems due to a shortage of rolling stock.[22]

Sleeper trains

The Alexandria–Cairo–Luxor–Aswan route is served daily in both directions by air-conditioned sleeper trains of Abela Egypt.[23] This service is especially attractive to tourists who can spend the night on the train as it covers the stretch between Cairo and Luxor. A luxury express train also links Cairo with Marsa Matruh towards the Libyan border.

Locomotives

Current

The vast majority of ENR locomotives are diesel. These include:

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Remarks | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||

| EMD G12 | Bo-Bo Diesel locomotive | 97 | Numbers 3701-3797 | ||||

| EMD G16 | Co-Co Diesel locomotive | 16 | Numbers 3301-3316 | 1960-1961 | |||

| EMD G16W | Co-Co Diesel locomotive | 45 | Numbers 3317-3361 | 1964-1965 | |||

| EMD G22 Series | Diesel locomotive | 32 | Numbers 3801-3832 | 1977 | |||

| EMD G22CU | Diesel locomotive | ||||||

| EMD G8 | Diesel locomotive | Numbered in 3200 series | |||||

| GA DE900 | Bo-Bo Diesel locomotive | 30 | 2000 | ||||

In 2009 ENR began taking delivery of 40 Electro-Motive Diesel JT42CWRM (Series 66) locomotives for passenger services.[24]

- Diesel locomotive at Ramses Station, Cairo in 2005

ENR diesel locomotive in 2006

ENR diesel locomotive in 2006

2160 working a passenger train near Aswan

2160 working a passenger train near Aswan

Retired

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Remarks | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||

| 545 | 2-6-0 Steam locomotive | 80 | Built by several companies | 1928-1931 | |||

| 8F | 2-8-0 Steam locomotive | 40 | Former War Department locomotives. Sold to Railways. Series 9301-915, 9317-9320, 9322-9342. |

1935-1946 | |||

| 4211 | 0-6-0 Diesel locomotive | 42 | Built by Arnold Jung Lokomotivfabrik | 1953-1956 | |||

Bus & ferry services

ENR serves a number of places by bus services including Abu Simbel (bus/ferry), Sharm el Sheik, Siwa Oasis, and Hurghada.

Accidents

- January 14, 2013 Badrashin train accident

- November 17, 2012 Manfalut train accident: Train crashes into a bus carrying school children at a level crossing near Manfalut, killing 51 and injuring 17.

- October 25, 2009: Collision at Al-Ayyat in Giza, 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of Cairo. According to a security official an initial report stated that 30 people were suspected killed and 50 injured.[25]

- September 4, 2006: A passenger train collides with a freight train north of Cairo, killing five and injuring 30.[26]

- August 21, 2006 Qalyoub rail crash: Two trains collide in the town of Qalyoub, 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Cairo, killing 57 people and injuring 128.

- February 20, 2002 Al Ayatt train disaster: A train packed to double capacity catches fire, 373 are killed.

- 2000: A train crashed into a minibus at an intersection south of Cairo, with 9 killed and two wounded.[27][28]

- November 1999: 10 killed between Cairo and Alexandria[29]

- April 1999: 10 killed in Northern Egypt head-on collision between two trains[29]

- 1998 Kafr Al-Dawar accident: "about 50" killed[27][29]

- 1997 2 major accidents: one with 14 killed, the other with 7 killed[27]

- 1995: Derailment just north of Cairo: 9 killed; Qiwisna accident (collision with bus): 49 killed; Beni Sweif accident: 75 killed[27][29]

- 1994 collision: more than 40 killed[27]

- 1993 collision: 40 killed[27]

- 1992 head-on collision at Al-Badrashin: 43 killed[27]

Problems

The debacle of the 2002 Al Ayyat railway accident showed significant deficiencies in the status and maintenance of the equipment. In the aftermath, the ERA initiated a program to update equipment and improve safety.[18] While some services have been privatized (i.e. food service, sleeper trains), ENR is considering further steps in privatization to increase efficiency and improve service. In addition, ENR has dormant real estate holding that it plans to utilize in a more profitable way.

The 2006 Qalyoub train collision led to further criticism of the management of the ENR raising issues of underfunding and corruption.[30] The head of the ERA, Hanafy Abdel-Qawi, was dismissed one day after the accident.[31] In response to the accidents an investment programme was launched in 2007 with the aim of modernising the rail network and improving safety standards.[32]

Major stations

Most major lines originate from Ramses Station, Cairo or Misr Station, Alexandria:

Railway links to adjacent countries

- Libya - railways under construction - Same gauge - 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)

- Sudan - no - Break-of-gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)/1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in)

- Gaza Strip - defunct since 1948

- Israel - defunct since 1948

Narrow Gauge

There is a modest network of narrow gauge railways at Kurna (the west Nile bank opposite Luxor). This has a gauge of approximately 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge and is used for transporting sugar cane. A smaller network of the same gauge and for the same purpose exists on the east bank, around the southern outskirts of Luxor.

Haulage is by diesel locomotive. Rolling stock includes rakes of bogie bolsters, typically seen loaded high up with sugar cane crop.

See also

References

- ↑ Directorate of Intelligence (2012-11-14). "The World Factbook - Egypt". Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Hughes, 1981, page 12

- ↑ Raafat, Jordan (1998-03-05). "Desert Train Heralds Train Tourism In Egypt". Jordan Star. Archived from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hughes, 1981, page 17

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hughes, 1981, page 15

- 1 2 3 4 Hughes, 1981, page 13

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hughes, 1981, page 32

- ↑ Sidney Peel, The Binding of the Nile and the New Soudan, Oxford, 1904

- ↑ Ewald Bloche, Constructing Modern Egypt:Modernization and Development Discourses in the Context of British and Egyptian Water Engineering, p.6-7 (Abstract)

- 1 2 "El Ferdan Swing Bridge". Structurae. Nicolas Janberg Internet Content Services. 1998–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Cotterell, 1984, page 137

- 1 2 "Gallery". Fun. Israel Railways. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam (1983). The Fateful Triangle. New York: South End Press. p. 194. ISBN 0-89608-187-7.

- ↑ Cotterell, 1984, page 136

- 1 2 3 "Welcome to the ENR Museum Page". Egyptian National Railways. Egyptian National Railways. 2010.

- 1 2 3 Proud & Smith, 1946, page 7

- 1 2 "CIA World Factbook". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- 1 2 3 4 "Strategies to improve safety". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ↑ "Egypt's Train Running Again". Railways Africa. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ↑ "Alstom wins €100m Egyptian signalling contract". Railway Gazette. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Alstom to deliver signalling equipment for Egyptian Railway". railway-technology. Kable. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "EGYPT’S LIMIT FOR EID IS 14 EXTRA TRAINS". Railways Africa. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "Abela sleeper trains". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ↑ "Commissioning of Egyptian JT42CWRM begins". Railway Gazette International. 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "Deadly train collision in Egypt". BBC. 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "Five dead in Egypt rail accident". BBC. 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fatemah Farag (2002-02-28). "One Way Ticket". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

- ↑ http://www.suezbalady.com/index.php/%D8%A3%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%AB/8818-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%B6-%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%AB-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1-%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%80-20-%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8B%D8%A7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AE%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A9

- 1 2 3 4 "Egypt's history of train disasters". BBC News. 20 February 2002. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Egypt's Minister Admits Railway Problems". Retrieved 2006-08-29.

- ↑ "National Rail Head fired over Train Tragedy". Egypt: The Daily Star. 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ "Egyptian investment will raise safety standards". Railway Gazette International. August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

Bibliography

- Cotterell, Paul (1984). The Railways of Palestine and Israel. Abingdon: Tourret Publishing. ISBN 0-905878-04-3.

- Goldfinch, Gary. Steel in the Sand - The History of Egypt & its Railways. ISBN 1-900467-15-1.

- Hughes, Hugh (1981). Middle East Railways. Harrow: Continental Railway Circle. ISBN 0-9503469-7-7.

- Proud, Peter; Smith, C, eds. (1946). The Standard Gauge Locomotives of the Egyptian State Railways and The Palestine Railways 1942-1945. London: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rail transport in Egypt. |

- Official website of the Egyptian Railways

- Map of System (Lower Egypt)

- Unofficial website with galleries

- Abela sleeper trains

- Mike’s Railway History: Egypt 1935

- Proposals

- More pictures of the narrow gauge lines