Great egret

| Great egret | |

|---|---|

_Tobago.jpg) | |

| Adult in Tobago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Ardea |

| Species: | A. alba |

| Binomial name | |

| Ardea alba Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

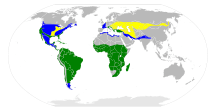

| Range of A. alba (excluding A. a. modesta) Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The great egret (Ardea alba), also known as the common egret, large egret or (in the Old World) great white egret[2] or great white heron[3][4][5] is a large, widely distributed egret, with four subspecies found in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and southern Europe. Distributed across most of the tropical and warmer temperate regions of the world. It builds tree nests in colonies close to water.

Systematics and taxonomy

Like all egrets, it is a member of the heron family, Ardeidae. Traditionally classified with the storks in the Ciconiiformes, the Ardeidae are closer relatives of pelicans and belong in the Pelecaniformes instead. The great egret—unlike the typical egrets—does not belong to the genus Egretta but together with the great herons is today placed in Ardea. In the past, however, it was sometimes placed in Egretta or separated in a monotypic genus Casmerodius.

The Old World population is often referred to as the great white egret". This species is sometimes confused with the great white heron of the Caribbean, which is a white morph of the closely related great blue heron.

The scientific name comes from Latin ardea "heron", and alba, "white".[6]

Subspecies

There are four subspecies in various parts of the world, which differ but little.[7] Differences are bare part coloration in the breeding season and size; the smallest A. a. modesta from Asia and Australasia some taxonomists consider a full species, the eastern great egret (Ardea modesta), but most scientists treat it as a subspecies.

- A. a. alba Linnaeus, 1758 – nominate, found in Europe

- A. a. egretta Gmelin, JF, 1789 – found in Americas

- A. a. melanorhynchos Wagler, 1827 – found in Africa

- A. a. modesta Gray, JE, 1831 – eastern great egret, found in India, Southeast Asia, and Oceania

Description

The great egret is a large heron with all-white plumage. Standing up to 1 m (3.3 ft) tall, this species can measure 80 to 104 cm (31 to 41 in) in length and have a wingspan of 131 to 170 cm (52 to 67 in).[8][9] Body mass can range from 700 to 1,500 g (1.5 to 3.3 lb), with an average of around 1,000 g (2.2 lb).[10] It is thus only slightly smaller than the great blue or grey heron (A. cinerea). Apart from size, the great egret can be distinguished from other white egrets by its yellow bill and black legs and feet, though the bill may become darker and the lower legs lighter in the breeding season. In breeding plumage, delicate ornamental feathers are borne on the back. Males and females are identical in appearance; juveniles look like non-breeding adults. Differentiated from the intermediate egret (Mesophoyx intermedius) by the gape, which extends well beyond the back of the eye in case of the great egret, but ends just behind the eye in case of the intermediate egret.

It has a slow flight, with its neck retracted. This is characteristic of herons and bitterns, and distinguishes them from storks, cranes, ibises, and spoonbills, which extend their necks in flight. The great egret walks with its neck extended and wings held close. The great egret is not normally a vocal bird; it gives a low hoarse croak when disturbed, and at breeding colonies, it often gives a loud croaking cuk cuk cuk and higher-pitched squawks.[11]

Distribution and conservation

The great egret is generally a very successful species with a large and expanding range, occurring worldwide in temperate and tropical habitats. It is ubiquitous across the Sun Belt of the United States and in the Neotropics.[1] In North America, large numbers of great egrets were killed around the end of the 19th century so that their plumes could be used to decorate hats. Numbers have since recovered as a result of conservation measures. Its range has expanded as far north as southern Canada. However, in some parts of the southern United States, its numbers have declined due to habitat loss, particularly wetland degradation through drainage, grazing, clearing, burning, increased salinity, groundwater extraction and invasion by exotic plants. Nevertheless, the species adapts well to human habitation and can be readily seen near wetlands and bodies of water in urban and suburban areas.[1]

The great egret is partially migratory, with northern hemisphere birds moving south from areas with colder winters. It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.

In 1953, the great egret in flight was chosen as the symbol of the National Audubon Society, which was formed in part to prevent the killing of birds for their feathers.[12][13]

On 22 May 2012, it was announced a pair of great egrets were nesting in the UK for the first time at the Shapwick Heath nature reserve in Somerset.[14] The species is a rare visitor to the UK and Ben Aviss of the BBC stated that the news could mean the UK's first great egret colony is established.[14][15] The following week, Kevin Anderson of Natural England confirmed a great egret chick had hatched, making it a new breeding bird record for the UK.[16] In 2017 seven nests in Somerset fledged 17 young.[17]

Ecology

The species breeds in colonies in trees close to large lakes with reed beds or other extensive wetlands, preferably at height of 10–40 feet (3.0–12.2 m).[11] It begins to breed at 2–3 years of age by forming monogamous pairs each season. It is unknown if the pairing carries over to the next season. The male selects the nest area, starts a nest and then attracts a female. The nest, made of sticks and lined with plant material, could be up to 3 feet across. Up to six bluish green eggs are laid at one time. Both sexes incubate the eggs and the incubation period is 23–26 days. The young are fed by regurgitation by both parents and they are able to fly within 6–7 weeks.[18]

Diet

The great egret feeds in shallow water or drier habitats, feeding mainly on fish, frogs, small mammals, and occasionally small reptiles and insects, spearing them with its long, sharp bill most of the time by standing still and allowing the prey to come within its striking distance of its bill which it uses as a spear. It will often wait motionless for prey, or slowly stalk its victim.

Parasites

A long-running field study (1962-2013) suggested that the central European great egrets host 17 different helminth species. Juvenile great egrets were shown to host fewer species, but the intensity of infection was higher in the juveniles than in the adult egrets. Of the digeneans found in central European great egrets, numerous species likely infected their definitive hosts outside of central Europe itself.[19]

In culture

The great egret is depicted on the reverse side of a 5-Brazilian reais banknote.

White Egrets is the title of Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott's fourteenth collection of poems.

The great egret is the symbol of the National Audubon Society.[20]

The name of venerable Shariputra, one of the Buddha's best known followers, signifies the son of the egret (among other possibilities), it is said that his mother had eyes like a great egret.[21]

In Belarus, there is a commemorative coin with the image of a great egret.

The great egret also features on the New Zealand $2 coin.

Gallery

- Egg, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

Adult in nonbreeding plumage

Adult in nonbreeding plumage_with_green_facial_skin.jpg) Bright green facial skin during breeding season

Bright green facial skin during breeding season Parent on nest with chicks

Parent on nest with chicks

References

- 1 2 3 BirdLife International (2015). "Ardea alba". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2015: e.T22697043A84959088. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ Royal Society for the Protection of Birds: Great white egret

- ↑ Bewick, Thomas (1809). "The Great White Heron (Ardea alba, Lin. – Le Heron blanc, Buff.)". Part II, Containing the History and Description of Water Birds. A History of British Birds. Newcastle: Edward Walker. p. 52.

- ↑ Bruun, B.; Delin, H.; Svenson, L. (1970). The Hamlyn Guide to Birds to Britain and Europe. London. p. 36. ISBN 0753709562.

- ↑ Ali, S. (1993). The Book of Indian Birds. Bombay: Bombay Natural History Society. ISBN 0195637313.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 37, 54. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2014). "IOC World Bird List (v 4.4)". doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.4.4. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Great Egret". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ "Animal Bytes – Egrets". Seaworld. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Dunning Jr., John B., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- 1 2 "Great Egret". Audubon Guide to North American Birds. July 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Timeline of Accomplishments". National Audubon Society. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ "Historical Highlights: Signature Species". National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 Aviss, Ben (22 May 2012). "Great white egrets nest in UK for first time". BBC Nature. BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ Aviss, Ben (31 May 2012). "Great white egrets breed in UK for first time". BBC Nature. BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ Hallett, Emma (31 May 2012). "Rare great white egret chick hatches in UK for first time". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ Adrian Pitches (2017). "England's Mediterranean Breeding Season". British Birds. 110 (9): 430.

- ↑ "Great Egret". All about birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ↑ Sitko, J.; Heneberg, P. (2015). "Composition, structure and pattern of helminth assemblages associated with central European herons (Ardeidae)". Parasitology International. 64: 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2014.10.009.

- ↑ "Great Egret (Ardea alba)". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ "A direct explanation of Heart Sutra". Purifymind. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ardea alba. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Ardea alba |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Great White Heron - The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Great White Egret - National Park Neusiedlersee Seewinkel in Austria

- Great Egret – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Great egret Ardea alba - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Ardea alba in the Flickr: Field Guide Birds of the World

- "Ardea alba". Avibase.

- "Great White Egret media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Great Egret photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)