Effects of Hurricane Isabel in Virginia

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

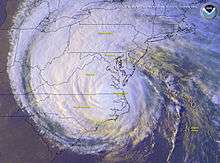

Satellite picture shows Hurricane Isabel entering Virginia as Category 1 storm. | |

| Winds |

1-minute sustained: 75 mph (120 km/h) Gusts: 105 mph (170 km/h) |

|---|---|

| Pressure | 969 mbar (hPa); 28.61 inHg |

| Fatalities | 10 direct, 26 indirect |

| Damage | $1.85 billion (2003 USD) |

| Areas affected | Virginia |

| Part of the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Other wikis | |

The effects of Hurricane Isabel in Virginia proved to be the costliest disaster in the history of Virginia.[1] Hurricane Isabel formed from a tropical wave on September 6, 2003 in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. It moved northwestward, and within an environment of light wind shear and warm waters it steadily strengthened to reach peak winds of 265 km/h (165 mph) on September 11. After fluctuating in intensity for four days, Isabel gradually weakened and made landfall on the Outer Banks of North Carolina with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) on September 18. It quickly weakened over land as it passed through central Virginia, and Isabel became extratropical over western Pennsylvania on September 19.

Strong winds from the hurricane affected 99 counties and cities in the state,[1][2] which downed thousands of trees and left about 1.8 million without power. The storm surge impacted much of the southeastern portion of the state, peaking at around 9 feet (2.7 m) in Richmond along the James River; the surge caused significant damage to homes along riverways. The nationwide maximum rainfall total from the hurricane was 20.2 inches (513 mm) in Sherando, Virginia. In the state's mountainous region, heavy rainfall caused severe and damaging flash flooding. The hurricane caused about $1.85 billion (2003 USD, $2.17 billion 2008 USD) in damage and 36 deaths in the state—10 directly from the storm's effects and 26 indirectly related.[3]

Preparations

By four days before Isabel made landfall, most weather models predicted Isabel to make landfall between North Carolina and New Jersey.[4][5] Initially, forecasters predicted it to move along the coastline of the Chesapeake Bay,[4] though as the hurricane neared land the predicted track was much closer to where it ultimately was. The National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane watch from the North Carolina/Virginia border to Chincoteague near its border with Maryland about 50 hours before Isabel struck land, including the southern portion of the Chesapeake Bay. 18 hours before the hurricane made landfall, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the watch to a hurricane warning for the entire coastline.[6] Additionally, inland hurricane and tropical storm warnings were issued for south-central Virginia. The Wakefield National Weather Service office issued three tornado warnings for four counties, though none became tornadoes. The office also issued two county-wide flood warnings and 43 flood warnings and flood statements for various river basins.[7]

The Virginia Emergency Management Agency was activated on September 15, about three days prior to Isabel making landfall and entering the state. Officials in Hampton issued the first mandatory evacuation in the state on September 17, about 35 hours prior to landfall. Eleven hours later, a mandatory evacuation was issued for some residents in Chesapeake, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach, with a recommended evacuation for some residents in the city of Suffolk and Isle of Wight, Northumberland, Richmond, and York counties. Later on September 17 Governor Mark Warner provided authorization for all recommended evacuations to become mandatory. By the time Isabel entered Virginia late on September 18, evacuations were also issued for Accomack County, Chincoteague, Gloucester County, Lancaster County, Mathews County, Newport News, Poquoson, Portsmouth, and Westmoreland County. The zones ordered to evacuate included residents along waterfronts, in areas prone to flooding, potentially affected by storm surge from a Category 2 hurricane, low-lying areas, health care facilities, or islands. The tools officials used to determine the evacuation zones included shelter locations, the SLOSH storm surge model, evacuation maps, and clearance times.[8]

Despite the orders, a relatively small number of people evacuated for the hurricane. According to a telephone survey conducted by the United States Department of Commerce, the highest participation rate was for residents in the Northern Neck in areas potentially affected by the storm surge from a Category 2 hurricane, of which 41% in the survey stated they left their houses for a safer location. In Surry, only 9% of those in a Category 2 hurricane storm surge zone left. 30% who participated in the survey along the Eastern Shore left. The primary reasons for the choice whether to evacuate or not were due to the track of Isabel, its strength, or influence from the media. Most participants in the survey stated they did not hear any sort of evacuation notice from public officials in their location, however. Of those who evacuated, about 64% left for the house of a friend or a relative, with about 24% evacuating to a hotel or a motel. Most of those in Hampton and Norfolk left for elsewhere in the state, while the majority of those in the Northern Neck evacuated to destinations in their own neighborhood or community. The evacuation destinations on the Eastern Shore of Virginia were varied, with 23% leaving for Maryland and 46% staying in their own neighborhood or community. The length of the evacuation process varied between a few hours to two days, with the worst evacuation problems being closed or flooded roads.[8] The Virginia Army National Guard and State Police troopers assisted in the evacuations.[9] In all, more than 160,000 residents in southeastern Virginia were told to evacuate, including 11,000 in vulnerable locations along the Chesapeake Bay[10] and all residents in mobile home parks in Chesapeake and Newport News.[11] A total of about 16,325 people evacuated to 67 shelters. Some of the reported problems were shortages of supplies, unanticipated medical issues, overcrowding, and lack of security.[8]

United States Navy officials in Norfolk ordered more than 40 destroyers, frigates, and amphibious ships out to sea to avoid any potential damage from the hurricane.[12] Officials at the Langley Air Force Base in Hampton ordered about 6,000 workers to evacuate elsewhere, due to its vulnerability to flooding.[10] About 350 National Guard workers assisted boat owners in the southeastern portion of the state. In Mathews County, two boat owners experienced fatal heart attacks as they worked to protect their boats. Officials distributed sandbags throughout the state for residents in flood-prone areas, including about 10,000 in the city of Alexandria.[13] Prior to the arrival of the hurricane, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel was closed, as were all campgrounds along the Blue Ridge Parkway and the primary parkway in Roanoke.[9] In Chincoteague, the famous Chincoteague Ponies were moved by volunteer firefighters to grounds of about 20 feet (6.1 m) higher. Officials closed schools, government offices, and businesses across the eastern portion of the state, leaving usually heavily congested roads as empty streets. Additionally, officials canceled trains along the Washington Metro, the Virginia Railway Express, and Amtrak lines, and several flights in and out of the Richmond International Airport.[13]

Impact

Throughout the state, Hurricane Isabel resulted in a damage total of $1.85 billion (2003 USD, $2.17 billion 2008 USD).[3] The hurricane destroyed more than 1,186 homes and 77 businesses, severely damaged 9,110 homes and 333 businesses, and left 107,908 homes and over 1,000 businesses with minor damage. Across the state, the hurricane generated an estimated 660,000 dump trucks of debris. At least ten people were directly killed by the storm, and hundreds more were injured.[14] A total of 1.8 million electrical customers were left without power,[7] with electrical damage totaling $128 million (2003 USD, $150 million 2008 USD).[14] Dominion Virginia Power reported 2,311 broken utility poles, 3,899 snapped crossarms, and 7,363 spans of downed power lines, with 72% of its primary distribution circuits damaged.[15] The passage of the hurricane resulted in an agricultural damage total of about $117 million (2003 USD, $137 million 2008 USD).[14]

Hampton Roads Metropolitan Area and Delmarva Peninsula

Along the Eastern Shore of Virginia, Isabel produced sustained winds reaching 50 mph (80 km/h) with gusts to 62 mph (100 km/h) at Wallops Island. Higher unofficial gusts were recorded, including a peak reading of 71 mph (114 km/h) in Chincoteague. Rainfall was fairly light, with 2 inches (51 mm) recorded in Heathsville.[16] On Fisherman Island, the hurricane produced a 4.26-foot (1.3-m) storm surge, flooding much of the island. The combination of the surge and waves resulted in minor beach erosion and overwash.[17] Northampton County reported $10 million in crop damage (2003 USD, $12 million 2008 USD).[1] One person died in Accomack County when a tree fell on his mobile home.[7]

In the Hampton Roads region, Isabel produced a high storm surge, including reports of 7.5 feet (2.3 m) at the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel and a peak of 8.3 feet (2.5 m) at Gloucester Point. Unofficially higher amounts included an estimate of 10.75 feet (3.28 m) at Smithfield.[6] In some locations, the surge surpassed the previous record set by the 1933 Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane.[16] Despite being classified as a hurricane while crossing the state, sustained winds only peaked at 70 mph (110 km/h) at Gloucester Point, 4 mph (6.4 km/h) less than minimum hurricane intensity. Hurricane-force wind gusts were recorded at multiple locations, with a 91 mph (146 km/h) reading at Gloucester Point and unofficial reports peaking at 107 mph (172 km/h) on Gwynns Island.[6] Additionally, Chesapeake Light, located 12 miles (19 km) east of Virginia Beach, reported a peak wind gust of 107 mph (172 km/h). The hurricane produced heavy rainfall in the Hampton Roads area, reaching 10.6 inches (270 mm) at James City.[16] The outer rainbands of Isabel spawned a 150-foot (46 m) wide F0 tornado in Nottoway County near Crewe, the only confirmed tornado during the passage of the hurricane. However, many people in the city of Norfolk reported that there was a tornado in that city as well. The tornado lasted a short amount of time and caused no known damage.[18][19] Strong waves, which reached 20 feet (6.1 m) in height offshore, caused severe beach erosion in Hampton, Newport News, and other locations along the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay.[16]

In Virginia Beach, the 15th Street fishing pier was significantly damaged due to intense wave action. Likewise the historic Harrison's Pier in the Ocean View area of Norfolk was completely destroyed. Many private piers and some public ones along the coastline were destroyed or damaged from the waves and storm surge, including a destroyed pier each in Buckroe Beach and Lynnhaven.[16] Moderate winds caused light damage to roofs and siding of oceanfront homes and hotels. In Virginia Beach, beach erosion and coastal flooding was minimal, credited due to a $125 million beach expansion project.[20] Several bridges in the Hampton Roads area were closed due to the hurricane.[9] The strong storm surge surpassed the floodgate to the Midtown Tunnel while workers attempted to close the gate. About 44 million US gallons (170,000 m3) of water from the Elizabeth River flooded the tunnel entirely in just 40 minutes, with the workers barely able to escape. The flooding left the tunnel damaged and closed for nearly a month.[21]

Heavy rainfall led to moderate to severe inland flooding, with high waters reported along U.S. Route 460 in Prince George County, U.S. Route 17, and several other roads. The rainfall led to river flooding, including minor to moderate flooding along the Rivanna and James Rivers, moderate flooding along the Appomattox River, and moderate to major flooding along the Meherrin, Nottoway, and Blackwater Rivers.[16] In Isle of Wight County, a driver attempted to cross high water on the James River Bridge and was killed when the water washed the car off of the road.[7]

The unusually large wind field uprooted many thousands of trees, downed many power lines, damaged hundreds of houses, and snapped thousands of telephone poles and cross arms. Hundreds of roads, including major highways, were blocked by fallen trees.[22] An emergency evacuation shelter in Newport News reported minor wind damage.[8] Two people in the region died due to falling trees—one in New Kent County and one in the city of Hopewell.[7] Power outages left most traffic lights not working across Hampton Roads, resulting in multiple minor car accidents. Additionally, most gas stations were closed, due to power outages leaving the pumps unusable.[20] Old Dominion University remained closed for two weeks due to storm damage and power issues, the longest it has ever been closed during a school term. Likewise, Norfolk State University, Regent University, Tidewater Community College and Eastern Virginia Medical School all experienced significant closing times due to both storm damage and a lack of electricity.

Northern

Funnel clouds were reported along the Northern Neck.[18] The hurricane produced a strong storm surge across northern Virginia, reaching 9.5 feet (2.9 m) in Alexandria.[14] Rainfall was light across the region, with amounts varying between 1–3 inches (25–75 mm).[23]

The storm surge washed out 160 homes and 60 condominiums in Fairfax County, with an additional 2,000 units reporting minor to severe damage from the flooding. In Stafford County, the surge destroyed five marinas and broke many boats free from their docks, while in Alexandria it flooded numerous businesses and severely impacting marinas. One section of CSX Transportation railway tracks in Prince William County collapsed into the Potomac River from the surge.[14]

Gusty winds downed several trees across Alexandria, causing about $2 million in damage (2003 USD, $2.3 million 2008 USD).[14] In Arlington County, flooding and downed trees destroyed two houses and damaged 192 homes, 46 severely. The storm surge flooded a parking lot at the Reagan National Airport. Damage in the county totaled $2.5 million (2003 USD, $2.9 million 2008 USD).[14] Falling trees caused major damage to 15 homes in the city of Fairfax, and damage throughout Fairfax County totaled $18 million (2003 USD, $21 million 2008 USD).[14] Four homes and 20 businesses in King George County were severely damaged, with an additional 150–200 reporting lesser damage from winds and falling trees. Gusty winds forced the closure of the Governor Harry W. Nice Memorial Bridge.[14] In Prince William County, seven homes were destroyed, with 24 homes and three businesses experiencing major damage. Several roads were closed due to downed trees. The Marine Corps Base Quantico reported severe damage amounting to $9.5 million (2003 USD, $11 million 2008 USD). Damage included a destroyed marina from flooding, with falling trees damaging buildings and vehicles.[14] Additionally, fallen trees severely damaged 31 homes and caused minor damage to 68 more in Stafford County.[14] The roof of a shelter in Mathews County was partially blown off.[8] A power outage in Northumberland County caused the NOAA Weather Radio Station in Heathsville to go off the air during the height of the storm, leaving the transmitter out of service for several days.[7]

Central and southwest

A tornado was reported near Emporia, though this was not later confirmed.[24] The storm surge tracked into the central portion of the state, with a site on the James River in Richmond reporting an estimated surge of about 9 feet (2.7 m), about 103 river miles (166 km) from its confluence with the lower Chesapeake Bay. Additionally, widespread areas of heavy rainfall of over 5 inches (130 mm) led to flooding of rivers.[7] Richmond set a new daily rainfall record from the precipitation from Isabel.[13] Strong winds were reported throughout the region, and wind gusts reached 73 mph (117 km/h) at Richmond International Airport.[25]

The storm surge significantly damaged or destroyed many homes along the James River, particularly in the towns of Claremont and Burwells Bay, Virginia. The surges in several tidal rivers caught some residents by surprise, both in height and severity. A man in Henrico County drowned after crashing into a flooded creek.[7]

The winds downed trees throughout the area, some of which hit homes and vehicles. In Amelia County, strong winds removed a mobile home from its foundation and destroyed it.[18] Falling trees killed two in the area—one in Chesterfield County and one in the city of Richmond.[7] The downed trees snapped many power lines, leaving about 365,000 Dominion Virginia Power customers in the Richmond area without power.[13] A portion of the roof of The Diamond, home of the Richmond Braves, was damaged by the winds.[26]

Wet conditions caused many accidents along roadways in central Virginia.[13] A motorist on Interstate 95 in Richmond died when he hydroplaned and crashed his car. In Albemarle County, a popular forest boardwalk that was part of the Monticello property was destroyed by a falling oak tree.[27] Also in Albemarle, two people were killed when their car drove off a road and crashed into a tree during heavy rainfall. A man in Chesterfield County died when struck by a tree. Three people died when a car in southern Fluvanna County crashed into a tree.[9] The deaths were considered indirectly related to the storm.[7] In south-central Virginia, strong winds produced widespread wind damage, with numerous trees and power lines reported down. In Campbell County, two homes were destroyed and ten others suffered minor damage. One residence in Amherst County suffered minor damage, and in Appomattox County one home reported major damage. In Buckingham County, one home was destroyed, three reported major damage, and one business suffered minor damage, while in Charlotte County, two homes were destroyed, 30 homes suffered major damage, and five businesses suffered minor damage. The storm destroyed one home and damaged 20, severely damaged three businesses, and caused some crop damage in Pittsylvania County. Monetary damage in the region totaled about $3 million (2003 USD; $4 million 2008 USD).[28]

Shenandoah Valley

Intense rainbands from Isabel produced heavy rainfall across the Shenandoah Valley,[29] peaking at 20.2 inches (513 mm) in Upper Sherando in Augusta County.[23] Sustained winds in the area ranged from 25–50 mph (40–80 km/h), while wind gusts reached about 60 mph (97 km/h). Strong winds downed numerous trees and power lines, causing some power outages.[30]

The rainfall led to extensive flash flooding and river flooding, including along several tributaries of the South River. The rainfall also caused extensive surface runoff in higher terrains, which led to flow over emergency spillways.[7] Four spillways to dams flooded, causing damage, though none of them failed.[29] At the Mills Creek Dam, the water reached about 2.5 feet (0.76 m) above the emergency spill way,[7] causing $125,000 in damage to the dam (2003 USD). Water flowed down the Black Creek at 60 mph (97 km/h), washing out the bridge and several hundred feet of asphalt along several locations of State Route 608.[29] The South River at Waynesboro rapidly flooded and crested at nearly 13.9 feet (4.2 m), destroying four bridges and flooding downtown businesses in 2 feet (0.61 m)–3 feet (0.91 m) of water. There, emergency management personnel evacuated about 300 people due to the ensuing flooding, which caused about $250,000 in property damage (2003 USD; $293,000 2008 USD). In all, about 350 were evacuated in Augusta County, 21 of whom by boat. Damages to public roads and equipment in the area were estimated at $1 million (2003 USD; $1.2 million 2008 USD). 13 homes were destroyed, with three businesses and 64 other residencies reporting major damage—some reported over 1 foot (0.30 m) of mud in their homes. Damage in the Shenandoah Valley totaled about $29 million (2003 USD; $34 million 2008 USD). A man canoeing in high flood waters drowned in Harrisonburg, while two others drowned in a horse and buggy after crossing a low water bridge in Rockingham County. The flooding also killed 25–30 head of livestock.[7][29][31]

Aftermath

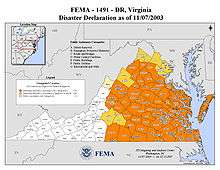

On the day of Isabel moving through the state, President George W. Bush declared 18 counties and 14 independent cities as disaster areas, making residents and business-owners there eligible for federal funding. Additionally, funds were allocated for state and local governments in the 31 designated jurisdictions to pay 75% of the eligible cost for debris removal and emergency services related to the hurricane, including requested emergency work undertaken by the federal government.[32] Many other jurisdictions were added, based on subsequent damage reports, and by September 22, 99 jurisdictions were eligible for disaster assistance.[33] The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided hurricane-related bulletins, including safety tips[34] and the method for removing hazardous materials.[35] By 12 days after the passage of the hurricane, FEMA distributed more than 6.3 million lbs. (2.9 million kg) of ice and 1.4 million US gallons (5,300 m3) of water to areas affected by Isabel. Disaster Recovery Centers, which contain information on the aftermath process, were opened in eight locations and received more than 1,850 inquiries. More than 350 FEMA inspectors visited homes to verify damages caused by Isabel, and by the end of September 2003 about 12,000 inspections were completed. In response to the power outages, FEMA installed 28 generators at disaster-affected critical public facilities to support life-sustaining community needs.[36] By about four months after the hurricane, 93,139 individuals in the designated areas applied for disaster assistance, while 20,417 people visited Disaster Recovery Centers throughout the state. The Small Business Administration approved more than 3,000 low-interest disaster loans from homes and businesses, with the value of the loans totaling $74 million (2003 USD; $87 million 2008 USD). The government provided $105 million (2003 USD; $123 million 2008 USD) for debris removal, emergency protective services, and permanent work, and approved about $25.9 million (2003 USD; $30.3 million 2008 USD) for life-sustaining needs such as water, ice, and generators at critical public facilities. Monetary assistance for temporary rental assistance and minimal home repairs totaled $32 million (2003 USD; $37 million 2008 USD), as well.[37]

Volunteer agencies arrived in the state to assist in the aftermath of the hurricane, and by about ten days after Isabel volunteers served more than 550,000 meals to affected residents;[38] over 933,000 meals were served during the four-month cleanup operation [39] Over 10 volunteer organizations, under the coordination of Virginia's Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster, worked to help individuals with debris removal across the state.[40]

Dominion Virginia Power quickly began to restore the widespread power outages with a workforce of about 11,000, working between 14 and 16 hours per day.[41] By two days after the storm, about 900,000 remained without power.[42] By five days after the storm, about 584,000 throughout the state were still without power,[15] and by ten days after Isabel the total dropped to about 160,000, most of whom were in the Hampton Roads area.[43] Improper use of generators caused three indirect storm deaths due to carbon monoxide poisoning resulting from improper ventilation of homes.[7]

As a result of polluted runoff from storm surge and heavy rains, the Virginia Department of Health forbade gathering shellfish in the Virginia portion of the Chesapeake Bay, as well as all rivers flowing into the bay.[44]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Isabel. |

References

- 1 2 3 Church World Service (2003). "The CWS Response" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ↑ Although the reference stated that 99 counties in Virginia were affected, the state has only 95 counties. Uniquely in the United States, all Virginia communities incorporated as cities are legally separate from any county.

- 1 2 National Weather Service (2006). "Virginia Hurricane History". Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- 1 2 Avila (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Thirty-Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Advisory Archive". Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- 1 2 3 Jack Beven; Hugh Cobb (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2004). "Hurricane Isabel Service Assessment" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Post, Buckley, Schuh and Jernigan (2005). "Hurricane Isabel Assessment, a Review of Hurricane Evacuation Study Products and Other Aspects of the National Hurricane Mitigation and Preparedness Program (NHMPP) in the Context of the Hurricane Isabel Response" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Bob Lewis (2003-09-19). "More than one million without power as Isabel churns through state". Associated Press.

- 1 2 Sonja Barsisic (2003-09-17). "Virginia governor gives green light to evacuations". Associated Press.

- ↑ Sonja Barsisic (2003-09-18). "Virginia governor gives green light to evacuations". Associated Press.

- ↑ Paul R. Yarnall (2005). "NavSource Online: Cruiser Photo Archive — USS MONTEREY (CG 61)". NavSource Naval History. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Peter Bacque; A.J. Hostetler (2003-09-19). "1.4 million in dark after Isabel hits". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2013-02-05. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Virginia". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- 1 2 Infrastructure Security; Energy Restoration (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Situation Report: September 23, 2003 (12:00 p.m.)" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wakefield, Virginia National Weather Service (2003). "Preliminary Post-Storm Report on Hurricane Isabel". Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ↑ T.R. Allen; G.F. Oertel (2005). "Landscape Modifications by Hurricane Isabel on Fisherman Island in Virginia" (PDF). Chesapeake Research Consortium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-07. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- 1 2 3 Bill Baskerville (2003-09-23). "Tornado adds insult to Isabel's injury". Associated Press.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Tornado". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- 1 2 Bill Geroux; Pamela Stallssmith; Lauren Shepherd (2003-09-20). "Beach localities roar back to life". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Sunbelt Rentals (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Effects by Region" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Southeast Virginia". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- 1 2 David Roth (2005). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Isabel". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Stuart Reid (2003-09-19). "Hurricane Isabel claims six lives". Edinburgh: Scotsman.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2003. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Central Virginia". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ↑ Meredith Fischer; et al. (2003-09-20). "One of the most devastating' storms, ever". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ↑ Spencer, Hawes (2003-10-23). "'Smithereens': Isabel KO's county's busiest trail". The Hook (newspaper). Charlottesville. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Southwest Virginia". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- 1 2 3 4 National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Shenandoah Valley". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Shenandoah Valley (2)". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Shenandoah Valley (3)". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "President Orders Disaster Aid For Virginia Hurricane Recovery". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "43 Jurisdictions Added To Hurricane Isabel Disaster Declaration". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "Post-Hurricane Safety Tips". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "Removing Potentially Hazardous Debris From Hurricane Isabel". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "Disaster Assistance Update". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ FEMA (2004). "Commonwealth Receives Nearly $257 Million In Disaster Assistance". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "Disaster Assistance Report". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ Baptist Press -States coordinating Isabel relief; chainsaw volunteers needed - News with a Christian Perspective Archived March 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ FEMA (2003). "Volunteers To Help With Debris Removal And Clean-Up". Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ Infrastructure Security; Energy Restoration (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Situation Report- September 24, 2003 (7:00 AM)" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Infrastructure Security; Energy Restoration (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Situation Report: September 21, 2003 (12:00 p.m.)" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Infrastructure Security; Energy Restoration (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Situation Report- September 28, 2003 (8:00 AM)" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Various (2003). "News Stories of Hurricane Isabel". Retrieved 2007-01-24.