Edward M. House

| Colonel Edward M. House | |

|---|---|

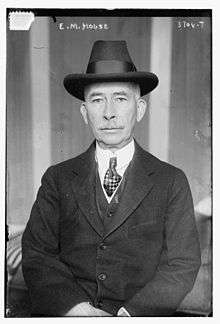

Edward M. House in 1915 | |

| Born |

Edward Mandell House July 26, 1858 Houston, Texas |

| Died |

March 28, 1938 (aged 79) New York City |

| Resting place | Glenwood Cemetery (Houston, Texas) |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Spouse(s) |

Loulie Hunter (m. 1881; his death 1938) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | six older brothers |

| Notes | |

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was a powerful American diplomat, politician, and advisor to President Woodrow Wilson. He was commonly known by the courtesy title Colonel House, although he had no military service. He was a highly influential back-stage politician in Texas before becoming a key supporter of the presidential bid of Wilson in 1912. Having a self-effacing manner, he did not hold office but was an "executive agent," Wilson's chief advisor on European politics and diplomacy during World War I (1914–18) and at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. In 1919 Wilson, suffering from a series of small strokes, broke with House and many other top advisors, believing they had deceived him at Paris.

Early years

He was born July 26, 1858 in Houston, Texas, the last of seven children. His father, Thomas William House, Sr., was an immigrant from England by way of New Orleans who became a prominent Houston businessman with a large role in developing the city and served a term as its mayor. An ardent Confederate, he had also sent blockade runners against the Union blockade in the Gulf of Mexico during the American Civil War.[1][4]

House attended Houston Academy, a school in Bath, England, a prep school in Virginia, and Hopkins Grammar School, New Haven, Connecticut.[1] He went on to study at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York in 1877 where he was a member of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity. He left at the beginning of his third year to care for his sick father, who died in 1880.[1][3][5][6]

He married Loulie Hunter on August 4, 1881.[3]

Texas business and politics

On his return to Texas, House ran his family's business. He eventually sold the cotton plantations, and invested in banking. He was a founder of the Trinity and Brazos Valley Railway. House moved to New York City about 1902.

In 1912, House published anonymously a novel called Philip Dru: Administrator, in which the title character, Dru, leads the democratic western U.S. in a civil war against the plutocratic East, becoming the dictator of America. Dru as dictator imposes a series of reforms which resemble the Bull Moose platform of 1912 and then vanishes.[7]

House helped to make four men governor of Texas: James S. Hogg (1892), Charles A. Culberson (1894), Joseph D. Sayers (1898), and S. W. T. Lanham (1902). After the election House acted as unofficial advisor to each governor. Hogg gave House the title "Colonel" by appointing House to his staff.

A “cosmopolitan progressive” who examined political developments in Europe, House was an admirer of the British Liberal welfare reforms instigated between 1906 and 1914, noting to a friend in June 1911 that David Lloyd George

“is working out the problems which are nearest my heart and that is the equalization of opportunity …. The income tax, the employers’ liability act, the old age pension measure, the budget of last year and this insurance bill puts England well to the fore. We have touched these problems in America but lightly as yet but the soil is fallow.”[8]

Becomes advisor to Wilson

After House withdrew from Texas politics and moved to New York, he became an advisor, close friend and supporter of New Jersey governor Woodrow Wilson in 1911, and helped him win the Democratic presidential nomination in 1912. He became an intimate of Wilson and helped set up his administration.

House was offered the cabinet position of his choice (except for Secretary of State, which was already pledged to William Jennings Bryan) but declined, choosing instead "to serve wherever and whenever possible." House was even provided living quarters within the White House.

He continued as an advisor to Wilson particularly in the area of foreign affairs. House functioned as Wilson's chief negotiator in Europe during the negotiations for peace (1917–1919) and as chief deputy for Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference.

In the 1916 presidential election, House declined any public role but was Wilson's top campaign advisor: "he planned its structure; set its tone; guided its finance; chose speakers, tactics, and strategy; and, not least, handled the campaign's greatest asset and greatest potential liability: its brilliant but temperamental candidate."[9]

After Wilson's first wife died in 1914, the President was even closer to House. However, Wilson's second wife, Edith, of whom he had commissioned the Swiss-born American artist Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862–1947) to paint a portrait in 1916, disliked House, and his position weakened. It is believed that her personal animosity was significantly responsible for Wilson's eventual decision to break with House.

Diplomacy

House threw himself into world affairs, promoting Wilson's goal of brokering a peace to end World War I. He spent much of 1915 and 1916 in Europe, trying to negotiate peace through diplomacy. He was enthusiastic but lacked deep insight into European affairs and relied on the information received from British diplomats, especially the British foreign secretary Edward Grey, to shape his outlook. Nicholas Ferns argues that Grey's ideas meshed with House's. Grey's diplomatic goal was to establish close Anglo–American relations; he deliberately built a close relationship a close connection to further that aim. Thereby Grey re-enforced House's pro-Allied proclivities so that Wilson's chief advisor promoted the British position.[11]

After A German U-boat sank without warning the British passenger liner Lusitania on 7 May 1915, with 128 Americans among the 1198 dead, many Americans called for war. Wilson demanded that Germany respect America neutral rights, and especially not sink merchant ships or passenger liners without giving the passengers and crew the opportunity to get into lifeboats, as required by international law. Tension escalated with Germany, until Germany agreed to Wilson's terms. House felt that the war was an epic battle between democracy and autocracy; he argued the United States ought to help Britain and France win a limited Allied victory. However, Wilson still insisted on neutrality.

House played a major role in shaping wartime diplomacy. Wilson had House assemble "The Inquiry", a team of academic experts to devise efficient postwar solutions to all the world's problems. In September 1918, Wilson gave House the responsibility for preparing a constitution for a League of Nations. In October 1918, when Germany petitioned for peace based on the Fourteen Points, Wilson charged House with working out details of an armistice with the Allies.

Paris Conference

House helped Wilson outline his Fourteen Points and worked with the president on the drafting of the Treaty of Versailles and the Covenant of the League of Nations. House served on the League of Nations Commission on Mandates with Lord Milner and Lord Robert Cecil of Great Britain, Henri Simon[12] of France, Viscount Chinda of Japan, Guglielmo Marconi of Italy, and George Louis Beer as adviser. On May 30, 1919 House participated in a meeting in Paris which laid the groundwork for establishment of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). Throughout 1919, House urged Wilson to work with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to achieve ratification of the Versailles Treaty, but Wilson refused to deal with Lodge or any other senior Republican.

The conference revealed serious policy disagreements and personality conflicts between Wilson and House. Wilson became less tolerant and broke with his closest advisors, one after another. Later, he dismissed House's son-in-law, Gordon Auchincloss, from the American peace commission when it became known the young man was making derogatory comments about him.[13]

In February 1919, House took his place on the Council of Ten, where he negotiated compromises unacceptable to Wilson. The following month, Wilson returned to Paris. He decided that House had taken too many liberties in negotiations, and relegated him to the sidelines. After they returned to the US later that year, the two men never saw or spoke to each other again.[13]

In the 1920s, House strongly supported membership in both the League of Nations and the Permanent Court of International Justice.

In 1932, House supported Franklin D. Roosevelt for the presidency without joining his inner circle. Although he became disillusioned with the course of the New Deal after Roosevelt's election, he expressed his reservations only privately.

Death and legacy

House died on March 28, 1938 in New York City, following a bout of pleurisy and was buried at Glenwood Cemetery in Houston. House Park, a high school football stadium in Austin, Texas, stands on House's former horse pasture. The small farming community of Emhouse in north-central Navarro County, Texas was renamed from Lyford in his honor, as he had served as the superintendent of the railroad company that operated in the community.[14]

In 1944, in Darryl F. Zanuck's 20th Century Fox film, Wilson, Charles Halton portrayed Colonel House.

A statue of House, financed by Ignacy Jan Paderewski in 1932, is located at Skaryszewski Park in Warsaw.

Works

- Edward Mandell House and Charles Seymour. What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918–1919. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1921.

- Charles Seymour (ed.), The Intimate Papers of Colonel House. In 4 volumes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1928.

- Edward Mandell House. Philip Dru: Administrator: A Story of Tomorrow, 1920-1935. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1912

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Neu, Charles E. (June 15, 2010). "HOUSE, EDWARD MANDELL". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ↑ "Edward Mandell House". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Biography in Context. Detroit: Gale. 1998. GALE|K1631003142. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- 1 2 3 "Edward Mandell House". Dictionary of American Biography. Biography in Context. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1944. GALE|BT2310010933. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Beazley, Julia (June 15, 2010). "HOUSE, THOMAS WILLIAM". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ↑ "Alpha Delt - Alpha Delt Hall of Famevh us dgt da FB f". Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Zawel, Marc B. "PART ONE: The History of Alpha Delta Phi at Cornell" (PDF). A Comprehensive History of Alpha Delt Phi. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Lasch, pp. 230–35.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=g1IgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA69&dq=colonel+house+old-age+pensions&hl=en&sa=X&ei=yqUzVePQNMzsaKSNgSg&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=colonel%20house%20old-age%20pensions&f=false

- ↑ Godfrey Hodgson (2006). Woodrow Wilson's right hand: the life of Colonel Edward M. House. Yale University Press. p. 126.

- ↑ "Col. House Discusses Peace Outlook with Wilson". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. June 28, 1915. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ Nicolas Ferns, "Loyal Advisor? Colonel Edward House's Confidential Trips to Europe, 1913–1917." Diplomacy & Statecraft 24.3 (2013): 365-382.

- ↑ MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York, Random House, 2002

- 1 2 Berg, A. Scott (2013). Wilson. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-399-15921-3.

- ↑ Long, Christopher. "EMHOUSE, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

Further reading

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace (1963) on Paris, 1919

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the great betrayal (1945) on Senate defeat. conclusion-ch 22

- Bailey, Thomas A. A Diplomatic History of the American People (1980) ch 39-40.

- Bruce, Scot David, Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917-1919 (U of Nebraska Press, 2013).

- Butts, Robert H. An architect of the American century: Colonel Edward M. House and the modernization of United States diplomacy (Texas Christian UP, 2010).

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2011), a major scholarly biography

- Doenecke, Justus D. Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I (2014), historiography.

- Ferns, Nicholas. "Loyal Advisor? Colonel Edward House's Confidential Trips to Europe, 1913–1917." Diplomacy & Statecraft 24.3 (2013): 365-382.

- Floto, Inga. Colonel House in Paris: A Study of American Policy at the Paris Peace Conference 1919 (Princeton U. Press, 1980)

- Esposito, David M. "Imagined Power: The Secret Life of Colonel House." Historian (1998) 60#4 pp 741–755.online

- George, Alexander L. and Juliette George. Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House: A Personality Study. New York: Dover Publications, 1964.

- Hodgson, Godfrey. Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House. (2006); scholarly biography

- Larsen, Daniel. "British Intelligence and the 1916 Mediation Mission of Colonel Edward M. House." Intelligence and National Security 25.5 (2010): 682-704.

- Lasch, Christopher. The New Radicalism in America, 1889–1963: The Intellectual as a Social Type. (1965).

- Neu, Charles E. "Edward Mandell House," American National Biography, 2000.

- Neu, Charles E. Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner (2014); Scholarly biography online review

- Neu, Charles E. "In Search of Colonel Edward M. House: The Texas Years, 1858-1912." Southwestern Historical Quarterly (1989) 93#1 pp: 25-44. in JSTOR

- Richardson, Rupert N., Colonel Edward M. House: The Texas Years. 1964 .

- Startt, James D. "Colonel Edward M. House and the Journalists," American Journalism (2010) 27#3 pp 27–58.

- Walworth, Arthur (1986). Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

- Williams, Joyce G. Colonel House and Sir Edward Grey: A Study in Anglo-American Diplomacy (University Press of America, 1984)

Primary sources

- Link. Arthur C., ed. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson. In 69 volumes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1966–1994)

- Seymour, Charles, ed. The intimate papers of Colonel House (4 vols., 1928) online editiononline v1;

External links

Media related to Edward M. House at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edward M. House at Wikimedia Commons Works written by or about Edward M. House at Wikisource

Works written by or about Edward M. House at Wikisource- Col. Edward M. House correspondences(Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA)

- Works by Edward Mandell House at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward M. House at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Colonel House at Internet Archive

- Works by Edward M. House at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Philip Dru Administrator at Project Gutenberg

- An Onlooker in France 1917–1919 at Project Gutenberg

- Edward M. House at Find a Grave

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Herbert L. Pratt |

Cover of Time Magazine 25 June 1923 |

Succeeded by Andrew Mellon |