Edward John Trelawny

| Edward John Trelawny | |

|---|---|

|

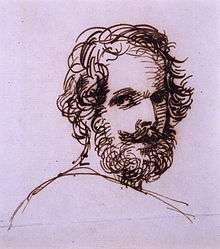

Edward John Trelawney by W. E. West | |

| Born |

13 November 1792 England |

| Died |

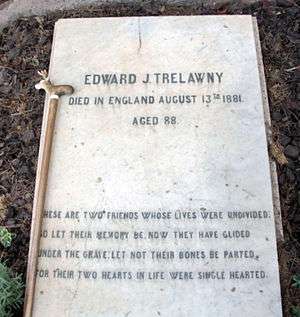

13 August 1881 (aged 88) Sompting, Sussex, England |

| Notable works |

Adventures of a Younger Son (1831) Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author (1878) |

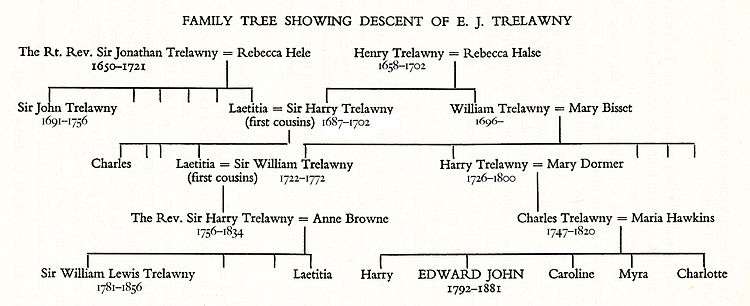

Edward John Trelawny (13 November 1792 – 13 August 1881) was a biographer, novelist and adventurer who is best known for his friendship with the Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. Trelawny was born in England to a family of modest income but extensive ancestral history. Though his father became wealthy while he was a child, Edward had an antagonistic relationship with him. After an unhappy childhood, he was sent away to a school. He was assigned as a volunteer in the Royal Navy shortly before he turned thirteen.

Trelawny served on multiple ships as a naval volunteer while in his teen years. He traveled to India and saw combat during engagements with the French Navy. He did not care for the naval lifestyle, however, and left at nineteen years of age without becoming a commissioned officer. After retiring from the navy, he had a brief and unhappy marriage in England. He then moved to Switzerland and later Italy where he met Shelley and Byron. He became friends with the two poets, and helped teach them about sailing. He enjoyed inventing elaborate stories about his time in the navy, and in one he claimed to have deserted and become a pirate in India. After Shelley's death, Trelawny identified his body and arranged the funeral and burial.

Trelawny then travelled to Greece with Lord Byron in order to fight in the Greek War of Independence. Byron and Trelawny split up near Greece and Trelawny travelled into Greece to act as the agent of Lord Byron. After Byron died, Trelawny oversaw the preparations for the funeral and the return of his body to England. He also wrote his obituaries. Trelawny joined the cause of the Greek Warlord Odysseas Androutsos and helped to provide him with additional arms. He also married Odysseas' sister Teritza. After Odysseas fell out of favour with the Greek government and was arrested, Trelawny took control of his mountain fortress. During this time, Trelawny survived an assassination attempt. After leaving Greece, he divorced Teritza and returned to England. In England he was well received by members of London society. He then wrote a memoir titled Adventures of a Younger Son. After the book was published he travelled to America for two years before returning to England. He then became politically active but soon remarried and moved to the English countryside.

He then lived the life of a country squire for 12 years and raised a family with his third wife. They eventually separated and he moved back to London with a mistress. He then wrote a well received book about Shelley and Byron. He soon became friends with several prominent artists and writers in London. He was able to share his firsthand experience with Romantic Era writers with the leading Victorian writers of the day. He later retired to Sompting, where he led an ascetic lifestyle. He died in Sompting at the age of 88, having outlived almost all of his friends from the Romantic era.

Early life

Trelawny's birthplace is unknown, although he claimed that he was born in Cornwall. Some of his biographers have contended that he was actually born in London.[1] His father, Charles Trelawny-Brereton, was a British military officer who retired after reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel.[2] His mother, Maria Hawkins, was of Cornish descent.[3][4] She had inherited a small sum of money from her father, but the family soon spent most of the inheritance. When Edward was six years of age, his father inherited a large sum of money from one of his wealthy cousins. The family soon used the inheritance to move to London, where they lived in a large house. As a condition of receiving the inheritance, his father was required to adopt the last name "Brereton". His cousin, Owen Brereton, wished to have his last name continued along with his wealth.[2] They lived in Cheshire while Edward was a young man.[1]

Although he was christened Edward John, his family generally referred to him as John when he was young. He later began referring to himself as Edward, which was the name used by most of his friends. Later in his life he referred to himself as "John Edward" for several years. Edward later recalled that his father had a fierce temper. He described his father's disposition as often "tyrannical". His father also tried to calculate the financial worth of all his relatives and kept detailed records of the numbers.[2] In addition to his father, many of Edward Trelawny's other ancestors had strong tempers, as well.[5] His elder uncle on his mother's side, Sir Christopher Hawkins was also wealthy. He held a seat in the House of Commons and in 1809 Trelawny's father also became a Member of the British Parliament.[6] As a child, he was often told of the long history and adventures of his ancestors in the Trelawny family. As an adult, he was very proud of having such prestigious ancestors.[7] The recorded history of his family dated back to the reign of Edward the Confessor and included many prominent citizens.[8]

Edward had five siblings who survived to adulthood and several who died as children. Edward shared a disdain for his father with his siblings. Though he hated his father, Edward was very close with his mother. His mother worked very hard to find wealthy husbands for her daughters, to the extent that her actions were satirised by some. In addition, many people found her to be a very disagreeable person as she grew older.[6] Trelawny's parents regarded their children as potential sinners and frequently used very harsh measures to try to instill a sense of discipline in them. He resented being treated in this manner.[8][9]

Edward only had one brother, Harry Trelawny. They were close in age and were very close friends during their childhood.[1] Harry was very quiet and reserved, which sharply contrasted with Edward's extroverted and confrontational personality.[9]

As an adult, Edward Trelawny often told stories about his childhood that focused on his early willingness to take confrontational positions and conceal things from others.[10] One often used story described the time that he killed a vicious Raven which had belonged to his father. He cited this event as an example of his habit of accepting offences up to a certain point before later taking revenge as the offences mounted. He later described the Raven incident in his autobiography, Adventures of a Younger Son.[11] In the book he described the fight with the raven as the "most awful duel" that he ever had.[12]

Education

At the age of eight Charles Brereton decided to send Edward to live at the Seyer school, which was located two miles from their home in Bristol at that time. Trelawny later claimed that his father had resisted sending him to the school for some time due to its cost, but decided to enroll him after he caught him stealing apples from an orchard in the back yard. Trelawny hated the school and was very angry at his father for sending him there. He often complained that the school served terrible food and subjected him to frequent flogging as a form of punishment.[13] In addition to flogging, one of his classmates recorded that caning was a frequent method of punishment there, as well.[14] The school's treatment of its students was actually comparable to many other schools of that time.[15] He was also bullied and treated cruelly by other students there.[16]

The schoolmaster there frequently condemned the French Revolution. These condemnations may have given Trelawny an early sympathy with revolutionary ideals.[14] He was expelled from the school after two years due to violent behaviour towards teachers as well as starting fires after being confined in his room as punishment.[17]

Naval career

Charles Brereton had originally hoped that his sons would attend Oxford. He became disappointed by the slow pace of Edward's learning as a child.[18] In October 1805, shortly before his thirteenth birthday, he enrolled Edward in the Royal Navy as a first class volunteer. The younger sons of the gentry traditionally entered the military at that time.[19] His family enrolled him as early as they could because seniority was crucial to career advancement at that time.[20]

His first experiences in the navy were serving on ships that had returned from the Battle of Trafalgar with many badly wounded sailors.[19] In November he was transferred to the Temeraire and then to the Colossus. He later attended a naval school in Portsmouth. In 1806 he served aboard the HMS Woolwich. While serving on the Woolwich he travelled to the Cape of Good Hope and to St. Helena. In 1808 he moved to the frigate Resistance, and in 1809 to the frigate Cornelia. While serving aboard the Cornelia he travelled to Bombay.[21] Trelawny's name was entered on the books of HMS Superb as volunteer first class in October 1812.[21]

Trelawny was initially happy to have joined the navy and enjoyed the rough lifestyle there.[22][23] He often exaggerated his age while he was in the navy. Some biographers believe he commanded a vessel as a midshipman in an engagement with the French at Mauritius in 1810.[24] Some also believe that he was wounded engaging the French in Java in August 1811. He left the Navy in 1812 at the age of 19; receiving a final settlement of pay in 1815.[25] He had grown to resent the discipline of the Navy due in part to the frequent punishment that he experienced. He was often sent to the masthead for several hours at a time.[26] During that time, he frequently entertained fantasies of mutiny and desertion.[27] Some biographers believe that Trelawny was inspired by hearing accounts of the French pirate Robert Surcouf.[28] He was never commissioned as a lieutenant, though many of his contemporaries were.[29] This disappointed him, although he began referring to himself as Lieutenant Trelawny anyway.[30]

First marriage

Trelawny returned to England in 1812. Soon after he arrived he fell in love with Caroline Addison. She was several years younger than him but as well educated and had studied French and was a skilled Pianist. Though both of their families disapproved of the match they were not dissuaded. Trelawny's father was particularly infuriated by his son's disobedience. They were married in May 1813 and first lived in London before moving to Bristol. After their first daughter was born in 1814, they experienced financial difficulties that forced Trelawny to ask his father for money.[30] Although he had a mutually disdainful relationship with his father,[31] he was able to secure extra funds. Edward and Caroline soon became unhappy, causing Edward to begin leaving home often to spend time with his friends[30] or to travel to the theatre by himself. Their second child was born in 1816.[32]

Caroline soon began having an affair with a much older man, a naval captain named Coleman. They successfully hid the affair from Trelawny for some time, he discovered it long after many others had known. Although he dearly wished to fight a duel with Coleman, he simply filed for divorce instead.[33] The proceedings were well covered in many of London’s "penny press" tabloid papers. This publicity caused Trelawny tremendous frustration and humiliation. The divorce order was granted in July 1817, but was not finalised until 1819.[32][34] Caroline was granted custody of the elder child and Edward kept the younger.[35]

Studies

Trelawny's father soon attempted to purchase him a commission in the British Army, but he refused to consider joining the army. His father was furious at his refusal, leading to their estrangement. Brereton became estranged with Harry around the same time, due to a marriage that he entered into against his father's wishes.[32] Edward began staying with a former landlord whom he had befriended.[33] She helped him find someone to take care of his child. Trelawny then began using the name "Edward" rather than "John".[35]

Due in part to the short time he spent in school, Trelawny struggled with spelling as a young man. He often spelled phonetically. This caused him significant difficulties when he tried to correspond with his friends. His spelling indicated a strong Westcountry accent. His parents were very concerned about this, particularly his habit of occasionally misspelling his own name. His problem with spelling might have been due to spelling dyslexia, evidence for which has been provided by one of Trelawny’s biographers.[36] After he left the Navy he read voraciously. He often read Shakespeare's Plays and attended the theatres in Covent Garden.[37] He began incorporating references to Shakespeare in his personal letters.[38] He also enjoyed reading the works of Lord Byron, including Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.[39] During this time he also accompanied his mother and sisters on a trip to Paris.[40]

Switzerland

Even though they often quarrelled, Charles Brereton continued to provide Trelawny with an allowance. He received an allowance of £300 a year, which was roughly the same amount as retired captains received as a pension at that time. He began to present himself as Captain Edward Trelawny, Royal Navy, Retired.[40] He decided to leave England to find a cheaper place to live. After initially considering a move to Buenos Aires, he decided to move to Switzerland.[34] In Switzerland he was not directly affected by the inflation that was occurring in England. After moving to Geneva he soon became bored by the city and spent much of his time hunting and fishing expeditions.[41] In the summer of 1820, while staying in Lausanne, Trelawny befriended a local bookseller. The bookseller soon recommended to him that he read Queen Mab by Percy Bysshe Shelley. This was the first time that he had heard of Percy Shelley. He read Queen Mab and he greatly enjoyed the work.[42]

He soon met Edward Ellerker Williams and Thomas Medwin at the home of a friend in Geneva.[43] He had served on the same ship as Williams in the navy, although not at the same time.[21] They also introduced him to the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley.[44]

In the fall of 1820 Trelawny learned that his father had died and returned to England from Switzerland.[44] After arriving in England he learned that he only had received a much smaller inheritance than he had expected. He was sorely disappointed and soon returned to Switzerland.[45]

Pisa

In early 1822 he travelled to Pisa to meet Edward Ellerker Williams and his wife Jane, Thomas Medwin, Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, and Lord Byron.[46] Trelawny greatly enjoyed meeting Percy and Mary Shelley after having looked forward to meeting them for some time. He also met Mary's half-sister Claire Clairmont.[47] Trelawny began spending much of his time with Mary Shelley. He often accompanied her to parties because Percy Shelley hated to do so.[48]

Trelawny had many similarities to Percy Shelley, including the fact that he had the same class, age, and preferences. He began to emulate Shelley in some additional ways, such as his attitudes toward authority figures.[49] Mary Shelley enjoyed his company, as well and was fascinated by the stories that Trelawny told of his naval career.[50] Lord Byron was initially surprised by the resemblance Trelawny bore to some of the pirates that he had written about, and once described Trelawny as the "personification of my Corsair".[51] In some ways, Trelawny did not fit in with his new friends due to his lack of wealth and education.[52] He had had more adventurous experiences than his friends by that time, however. He often exaggerated these experiences in conversation, especially when discussing the details of his naval career.[53]

Trelawny invented a fictional story of his activities as a teenager. The story featured him deserting from the navy and traveling throughout Asia. During this time he claimed to have formed a band of pirates who fought against the British Navy. His descriptions of his adventures often included duels and romance, such as his marrying an Arab girl name Zella who was later poisoned by a jealous rival. These stories were often violent, but his friends found them very exciting.[54] Trelawny often used real events as the baseline for his stories, and then greatly embellished the events that actually took place.[55] His biographers have been divided as to whether he intentionally exaggerated to create a persona or if he really came to believe the stories that he created.[56]

Trelawny greatly enjoyed his time in Pisa. He was very active during his time there and often practised boxing or fencing with his friends. He frequently attended theaters with them at night.[57] He also enjoyed listening to Jane Williams sing and play songs with the guitar that Shelley had given to her.[58]

In March Trelawny was involved in a high-profile confrontation that took place while he was travelling with Byron, Shelley, and some of their friends. The incident began when an Italian soldier confronted Count John Taafe, who was travelling with Shelley, Trelawny, Byron, and Byron's entourage. Although Shelley was slightly wounded as he fell from his horse chasing after the soldier, one of Byron's servants later caught the soldier and wounded him severely. The incident was very controversial and received a significant amount of publicity in Pisa. This was in part due to the anti-English sentiment that existed there at that time. After a lengthy investigation by the Italian authorities, Trelawny and his friends were cleared of all charges that had been pending against them.[58][59]

Shelley and Edward Williams had wanted to begin sailing for some time, and Trelawny used his naval experience to help them make plans.[60] Together they decided have an American style schooner constructed; he had often observed this type of boat during his time in the navy.[60][61] After Shelley and Williams had constructed their boat, the Don Juan, Trelawny was hired by Byron to be the Captain of his vessel, the Bolivar.[62] Trelawny also moved into a room in Byron's mansion at that time.[63] Trelawny's friend Daniel Roberts designed and supervised the construction of both vessels.[36] The construction of the Bolivar cost £750, a sum which Byron found irritatingly high.[64]

Trelawny had planned to accompany the Don Juan in the Bolivar during the voyage in which the Don Juan sank. He was held back by the Port Authority because he was not carrying his port clearance with him, though he had sailed without bringing his clearance several times in the past.[60][65] After Shelley and Williams did not return to their home by the time that they were expected, Jane Williams and Mary Shelley informed Trelawny that their husbands were missing. He began making urgent inquiries and attempted to find news about them. For the next several days, he frequently met with members of the Italian Coast Guard and promised them rewards if they were able to find the boat.[66]

After Shelley's body was found, Trelawny was able to confirm the identity of the body. He then notified their wives and escorted Mary and Jane to Pisa for the funeral.[67] Trelawny made the arrangements for the cremation and oversaw the ceremony. After Shelley's body was cremated, Trelawny removed what he thought was Shelley's unburned heart from the fire. He later wrote a full account of the funeral.[68] He also arranged to have a memorial built at Shelley's final resting place in Rome.[69] Trelawny then reserved a spot for himself in the same cemetery.[70]

After the funeral, Trelawny went on a hunting trip with Daniel Roberts.[71] After he returned, he soon developed tension with Byron, in part due to Byron's habit of leaving bills unpaid. This often put Trelawny in a difficult position as the captain of his boat.[72] Byron sold the Bolivar for 400 guineas in late 1822.[73][74] This left Trelawny unemployed. He split his time between Genoa and Albaro and hunted often. He began spending much of his time with Mary Shelley[74] and he supplied the funds for her to return to England. Trelawny soon fell in love with Claire Clairmont.[75] She ultimately spurned his proposals, however. He decided to move after his mother found his address and began sending him letters.[76]

Greece

Shelley had been very supportive of the idea of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire before he died.[77] In June 1823 Byron decided to go to Greece to fight for independence, and Trelawny enthusiastically accompanied him.[78] With the assistance of Captain Daniel Roberts, Byron chartered a boat named Hercules to transport them there.[36][79][80] During the voyage, Trelawny and Byron sometimes irritated each other. They often joined in swimming, boxing, and fencing together during the trip. They also practised their aim by shooting ducks for target practice.[36][81][82] They initially spent much time together because the rest of Byron's entourage suffered from seasickness and were unable to participate in their activities.[83][84] On the voyage, "Byron sometimes expressed his intention, should his services prove of no avail to Greece, of endeavouring to obtain by purchase, or otherwise, some small island in the South Sea, to which, after visiting England, he might retire for the remainder of his life, and very seriously asked Trelawny if he would accompany him, to which the latter, without hesitation, replied in the affirmative." [85] After they arrived in the Ionian Islands, Byron decided to stay there for a while in order to consult with the London Greek Committee and other experts regarding the political situation in Greece before proceeding further. They then left him in Kefalonia and traveled to Greece.[86] Byron approved of Trelawny's plan to travel deeper into Greece and presented him with a sword and a letter of introduction shortly before he departed. Byron also asked them to soon return to him with more information.[87]

After initially staying with a shepherd after they arrived in Greece, they travelled to Tripoli. Trelawny wore authentic Souliote dress on the journey. After arriving in Tripoli, Trelawny met with Alexandros Mavrokordatos whom he soon came to strongly dislike.[88] He also met Theodoros Kolokotronis, whom he later came to admire. They traveled together to Salamis, on the journey Trelawny viewed the sites of previous battles. He recorded that he could see the bones of those who had been slain there.[89] He spoke with many Greek leaders after arriving in Salamis. He was well respected as the agent of the Lord Byron, whom they held in high esteem. He frequently corresponded with Lord Byron and encouraged him to come to Greece.[90] He was disappointed when Byron did not come for some time, and that when he did come he came to territory that was overseen by Mavrokordatos. Trelawny, however, greatly enjoyed Corinth and Athens. Rumours later emerged that he purchased a harem of twelve to fifteen women while staying in Athens. However, some have maintained that he may have actually redeemed the women from slavery.[91][92]

He soon left on a raiding expedition with the warlord Odysseas Androutsos, who controlled much of Eastern Greece.[93] Trelawny thought very highly of Odysseas, describing him as a brother and comparing him to George Washington and Simón Bolívar.[94][95][96] During this time Trelawny commanded a group of twenty five Albanian soldiers.[96] In the winter of 1823–24, Odysseas and his men fought several battles with the Turks and destroyed villages in the Euboea region.[95] Trelawny lobbied Byron to send them more arms, but Byron decided to wait before shipping any to consider the political implications. Some have called into question the effectiveness of Odysseas' campaign and many view Byron's delay as a polite refusal.[97]

After Byron died in April 1824, Trelawny returned from an expedition with Odysseas. Trelawny claimed that upon arriving in Messolonghi, he began overseeing the funeral preparations.[98] In the days before his death, Byron often said he wished Trelawny would return to him. Trelawny then wrote several accounts of Byron's last years and sent them to papers in England. In these accounts he often exaggerated the role he played in Byron's life.[99] Shortly after Byron died, Trelawny reported he took the opportunity to view his deformed foot with a servant of Byron's.

Mountain fortress

Trelawny then began lobbying members of the London Greek Committee to fully support Odysseas.[100] He also lobbied for a Greek Congress and criticised Mavrokordatos.[101] In a letter to Mary Shelley Trelawny described Mavrokordatos as a "miserable Jew" and said that he hoped to see him beheaded.[94] Trelawny was able to transfer some portions of weapons shipments from London to Odysseas. This was a controversial move among Greek leaders and the London Greek Committee, many of whom saw it as a foolish move.[102] He also suggested that the Greek authorities should hire privateers to harass Turkish ships.[103]

In May 1824 Trelawny brought a load of guns to the fortified cave in which Odysseas was based. He arrived with a British military officer, Whitcomb, and a military engineer, Fenton.[104] Trelawny recorded that Odysseas commanded a force of 5,000 men, who killed over 20,000 people during their campaign.[105] Odysseas and his men retired to Parnassus after they learned the Greek government would not give them more funds. The Greek Government had decided to try to raise a regular army and take power away from the warlords. The size of his force soon diminished.[106]

Trelawny hoped to convince Odysseas to leave with him for the Ionian islands, but Odysseas refused. He also helped Odysseas hide some valuable antiquities, they were never found. Some sources claim that Odysseas was attempting to strike a deal with the Turks at that time.[107] Trelawny soon married Teritza, the half-sister of Odysseas. She was much younger than him, and was probably a teenager.[108] Some have speculated that their wedding was performed by a local Greek Orthodox priest.[109] Teritza then lived with him in the cave. At this point Trelawny's life had actually began to resemble many of the stories that he had previous constructed about his past.[108] Word soon spread to England that Trelawny was working for the Turks with Odysseas now.[110] Trelawny again tried to convince Odysseas to escape with him to the Ionian Islands in order to prevent the Greek government from arresting him.[109] Odysseas was caught on his way to find a boat.[109] He was charged with treason and imprisoned in Athens. Trelawny administered the cave in his absence.[111]

Assassination attempt

Tension between Trelawny and his two English companions Fenton and Whitcomb had been growing. When a shooting match was proposed, Trelawny arrogantly said that even with a pistol he could outshoot the other two with rifles.[112] During the contest, when Trelawny was checking the target, he was shot in the back by Whitcomb, who was urged on by Fenton. Fenton was quickly shot and killed by one of Trelawny's Greek soldiers. Seeing this, Whitcomb tried to flee but was captured by soldiers.[113] The soldiers initially hung Whitcomb off a cliff by his ankles as punishment, but Trelawny asked them to stop and they imprisoned the man. There was no doctor available and Trelawny lived on a diet of raw eggs that was suggested by his wife, who attended to him there. He needed to have a musket ball removed, however. His men soon kidnapped a Klept doctor and forced him to operate at gunpoint. The doctor's efforts were unsuccessful. Although Trelawny was in poor condition for several weeks he eventually recovered. His living assailant was later released. The soldiers wanted to roast Whitcomb alive, but Trelawny insisted on releasing him.[114]

Trelawny was bedridden for five weeks after he was shot. After word spread to England that Trelawny had survived, many of his relatives unsuccessfully lobbied the British government to extract him from Greece. The British Army Major D'Arcy Bacon learned of his situation and came to an agreement with Mavrokordatos to allow Trelawny to leave Greece.[115] Bacon went searching for Trelawny and was captured by some of Odysseas' soldiers. They had mistaken him for a doctor and hoped that he would operate on Trelawny.[114] A British Corvette sailed to Corinth to pick him up, Teritza accompanied him. His story was widely published in English newspapers then.[115] Some biographers believe that Fenton and Whitcomb were bribed by Mavrokordatos to kill Trelawny and give over the cave. Bacon successfully lobbied the Greek government to allow him to leave the country.[113] Odysseas was executed in Athens shortly before the attempt on Trelawny's life.[115] Trelawny regained full use of his arm, but he walked with a slight hunch after recovering from his injury.[116]

Return to England

Trelawny moved to Zante in May 1826 and stayed there for a year.[117] There he lived next to the house of Thomas Gordon.[118] While they were living in Zante, Teritza gave birth to their first child, Zella.[119]

He filed for divorce from Teritza in 1827 in Kefalonia after four years of marriage. There were later rumours that Trelawny had been abusive towards her and had forbidden her to wear non-Greek clothing.[117] Teritza then moved into a nunnery and gave birth to their second child there.[117][119] The child died at a very young age, however.[117][119] Teritza was awarded a small alimony and soon left the nunnery to remarry. Her second husband was a Greek Chieftain.[92]

Trelawny then returned to England to visit his family in Cornwall.[120] He also visited Mary Shelley, and asked her to consider entering a romantic relationship with him.[121] She refused his offers, however. He also briefly visited Claire Clairmont in Italy in 1828. Though he was very attracted to her, she too spurned his advances, although they did correspond with each other up until her death in 1879.[122]

In 1828 he began referring to himself as "John Edward Trelawny", but he returned to "Edward John Trelawny" three years later.[122] In late 1828 he returned to England and met with Thomas Jefferson Hogg and Jane Williams. He soon developed a strong dislike for Hogg.[123][124]

Trelawny then decided to write a book about his life and friendship with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron.[125] He initially had wanted to write about Shelley but abandoned the plan after he was unable to secure the assistance of Mary Shelley. He then decided to write about himself. He discussed many actual events in his life, but greatly embellished many details.[126] He also discussed radical politics in the book.[127]

In 1829 Trelawny made plans to live with his three daughters in Italy. He abandoned this plan after his eldest daughter died and his finances became strained. His financial problems were caused in part by a large gift to the Medwin family after they encountered financial difficulties.[128]

Adventures of a Younger Son

Trelawny wrote Adventures of a Younger Son in Arcetti while staying in a room that he rented from Charles Armitage Brown. Brown was irritated that Trelawny burned furniture for firewood, but agreed to copy edit the book for him.[129] He began work on the book in 1829 but did not finish it until 1831.[130] He was likely dyslexic and his draft required extensive editing by Brown.[131]

Trelawny then sent his draft to Mary Shelley to arrange publication under the title A Man's Life. Mary insisted on removing some passages from the book that could be viewed as offensive.[129] He decided to publish it anonymously, but it was expected that many would be able to guess his identity. He did not earn as much money from the publisher as he had hoped.[132] In Autumn 1831 his book was finally published.[133]

His book was published anonymously but within a month it had become well known that he was the author.[134] Most contemporary reviewers accepted the book as factual,[135] but subsequent scholarship has demonstrated that most of the book is no more than a fictional account of his life. Writing in the Keats-Shelley Journal of 1956, Anne Hill concluded that "the proportion of truth to fiction in Adventures of a younger son turns out to be small, not more than one tenth." His biography has since been translated into French, German, Swedish, and Gaelic.[79] Trelawny returned to England in 1832 and was famous and well received by London society and was treated like a hero. He began meeting with Godwin regularly.[135]

America

His younger daughter by his first wife was adopted by a British General and his youngest daughter was adopted by an Italian family. Trelawny's financial condition became much better around then.[136] In 1832, while on a visit to Liverpool, he decided to travel to the United States.[127] He arrived in Charleston in early 1833. He then travelled to New York in early summer. In New York he met Fenimore Cooper and Fanny Kemble.[137] They then travelled to Niagara. Wherever they went he often talked of staying permanently. He repeatedly raised political issues and furiously argued when disagreed with.[138] In August he decided to try to swim across the rapids below the falls. He successfully made it across, but nearly drowned on the way back.[139] He then travelled to Saratoga, New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia.[140] He then returned to Charleston, preferring the climate there. He was disappointed that his atheism was poorly received in the United States.[141] He later claimed to have travelled to California in 1833. He was bothered by the way that wealthy Americans tried to copy the habits of Europe.[142] It is unknown exactly what he did in late 1833 early 1834, some have speculated that he made plans to build a utopian community. He travelled to Philadelphia again by autumn 1834. He was very depressed at that time, and returned to England in spring 1835.

Philosophical Radicals

Upon his return to England, Trelawny became very politically active with a group known as the Philosophical Radicals. The group advocated left wing politics and often focused its efforts on the rights of women.[143] Trelawny began associating with its supporters, many of whom were among the upper class members of London society.[144] Most of London society was willing to overlook his claims of disloyalty against the British after his claimed desertion and accepted him into society.[145] At this time many women were attracted to him, and there was frequent speculation about his sexual escapades in many London tabloids, such as The Satirist.[146]

He soon had a falling out with Mary Shelley. He was offended in part because she turned to Thomas Jefferson Hogg for advice instead of asking him. He later described Mary as "the blab of blabs" in a letter to Claire Clairmont.[147] Trelawny and Mary Shelley also disagreed about a custody reform bill that was proposed by the Philosophic Radicals.[148]

During this time he published short stories about piracy.[149] In 1839 he disappeared from London society due to a controversial new romance.[150]

Third marriage

He moved into a villa on Putney Hill that was owned by John Temple Leader, a political friend of his.[151] His affair with Augusta Goring began shortly after he returned to England. She claimed to have been badly treated by her husband,[152] who was a member of Parliament. Many people in London society believed that he was practising a strict aesthetic routine there.[153] Trelawny then eloped with Augusta. After she separated from her husband she began using a pseudonym.[154] She gave birth to a son in August 1839.[153] Her husband tracked her down, however, and filed for divorce. The divorce was granted in 1841. Trelawny married Augusta and they settled in a small country town Usk and bought a farmhouse. They had a daughter Laetitia there as well.[154] They later moved to a large house on a 440-acre farm two miles outside Usk.[155] He worked hard maintaining the farm and was friends with several leading citizens from the town. He lived in Usk for twelve years total, which was longer than he had ever lived in one place in his entire life.[156] He planted trees and lawns and flower gardens.[157] Townspeople were offended by him breaking the sabbath.[158] In the mid-1850s he began writing a book about his memories of Byron and Shelley. His marriage split up in 1857 due to his relationship with a young woman who became his mistress and later common-law wife. The girl's name was never discovered; she is only known as Miss B.[159] He frequently had tea with the vicar of Usk on Sunday afternoons. After he separated from his wife in Usk he sold a large amount of the furniture and books and held a well attended open house for villagers to come in and buy his possessions.[160] After his third divorce, he criticised the institution of marriage in a letter to Claire.[161] He frequently wrote the wrong dates on his letters.[162]

Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron

Trelawny became friends with several artists and writers, including Algernon Charles Swinburne, Joseph Boehm, Edward Lear, and Richard Edgcumb.[163][164] He became a friend of Rossetti as he was working on a new edition of Shelley's poems.[164] In 1844 Robert Browning met with Trelawny in Italy.[165]

In 1858 Trelawny published Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron. This book was better received than previous biographies of Shelley, such as The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Although he had only known Shelley for six months,[165] Trelawny was thereafter recognised as the preeminent Shelley expert. His first memoir were republished then, as well.[166] He often edited his letters before they were published. The edits attempted to cover up some of his insecurities and defend his reputation. He frequently characterised himself as a survivor in his writings.[167]

Trelawny was then widely received in society[168] and met Benjamin Disraeli at a meeting that was held about possibly building a statue for Lord Byron.[169] Though he had never met her, Trelawny was often a defender of Percy Shelley's first wife Harriet. He often shocked people by applauding Shelley's atheism and disparaging Browning and Tennyson.[170] At the age of eighty he read On the Origin of Species and welcomed its conclusions. He greatly admired Garibaldi and John Brown, as well.[171]

Trelawny spoke with the French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme after he began work on a portrait of Shelley.[172] In 1878 Trelawny's memoir was reissued and edited by Rossetti under the title Records of Shelley Byron and the Author. This book contained somewhat harsher treatments of poets than the previous edition had been, some have speculated this may have been Rossetti's influence.[173] He was particularly critical of Mary Shelley, the Godwin family and Leigh Hunt.[174] Lady Shelley was furious, and had Trelawny's relics removed from the Shelley shrine.[173]

As he grew older, Trelawny's guests noted that he told them amazing stories about himself that he purported to be true, such as meeting with Captain Morgan and circumnavigating the Globe.[175]

Retirement

Trelawny then adopted a more ascetic life and moved to Sompting, Sussex.[176] There he lived near William Rossetti.[177] As he grew old he remained very active and did not hire a house keeper until he was very old.[178] He regularly swam, chopped wood and dug in his gardens. He remained active into his eighties. He made his garden into a bird sanctuary and did not allow hunters onto his property.[179] He was very friendly with the neighbourhood children and often gave them candy.[180] He corresponded with Claire regularly from 1859 until 1876.[181] He unsuccessfully tried to persuade Claire to write a biography of him.[182]

He often presented items to his friends and visitors that he claimed to have found on his world travels or from his days with Shelley and Byron.[183] As an old man he lived with a much younger woman, Emma Taylor. They told people she was his niece.[184]

He closely oversaw his sons' education and taught them foreign languages. They were sent to a military academy in Germany.[184] Frank died as a young man while serving as a soldier in the Prussian Army. His son Edward converted to Catholicism and told people that he was the son of Sir John Trelawny. They later became estranged.[185] Zella became a housewife in London.[186] Trelawny outlived four of his seven children. The only child that he enjoyed good relations with was Laetitia, who also lived with him in Sompting. He had chosen to name her Laetitia, as several women on Sir Johnathan’s side of the family were named Laetitia. Late in his life he became a teetotal vegetarian.[187]

In 1874 he sat as a model for John Everett Millais as he painted the picture The North West Passage. This picture depicted an old sailor declaring that England would find a way through the Northwest Passage.[177] Millais had seen Trelawny at the funeral of John Leech years before and decided that he would make the perfect figure for the drawing.[163] Trelawny initially liked the picture, but he was angered when he saw that Millais had included a glass of grog in the picture.[188] It was ultimately well received by critics.[189]

Trelawny was able to visit with Augusta Draper in 1874. He also visited with Jane Williams in 1872. Williams was the only close friend of Percy Shelley to outlive Trelawny.[190] In August 1881 he suffered a fall while out on a walk. He was bedridden and died two weeks later.[191] His ashes were buried in Rome in a plot of ground adjacent to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s grave. He had purchased this plot in 1822, at the time he had arranged for Shelley’s ashes to be reburied in a more suitable site within the Protestant Cemetery.[181] At his request his grave marker bears a quote from Shelley's poem "Epitaph".[192]

These are two friends whose lives were undivided:

So let their memory be, now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bones be parted,

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

Reception

There have been six biographies written about Trelawny. The characterizations of him vary greatly. Several of the authors were very negative in their portrayal of him, others presented a very favourable romantic portrait of him, and some have presented a mixed picture of his character. The authors of the biographies conducted varying amounts of scholarship and often contradicted each other about some details of Trelawny's life.[193] Trelawny has been credited with helping Byron and Shelley become recognized as celebrities after their deaths. Jonathan Bate has described him as one of the "key makers of modern celebrity". He was the last major figure of the Romantic Era living in Victorian England.[194]

Besides being the subject of numerous biographies, Trelawny is one of the primary characters in the novel Hide Me Among The Graves, by Tim Powers (William Morrow, 2012), as well as playing a major role in Shelley's Boat, by Julian Roach (Harbour Books, 2005).

References

- 1 2 3 Armstrong 1940, p. 9

- 1 2 3 St Clair 1977, p. 3

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 5

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 8

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 4

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 4

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 6

- 1 2 Armstrong 1940, p. 1

- 1 2 Armstrong 1940, p. 14

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 5

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 10

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 12

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 7

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 8

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 15

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 11

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 9

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 19

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 10

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 13

- 1 2 3 Prell 2008, p. 50

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 21

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 12

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 14

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 16

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 18

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 19

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 23

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 24

- 1 2 3 St Clair 1977, p. 25

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 17

- 1 2 3 St Clair 1977, p. 26

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 29

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 36

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 30

- 1 2 3 4 Prell 2011, p. 47

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 32

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 33

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 34

- 1 2 Prell 2011, p. 18

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 37

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 67

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 39

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 40

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 41

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 43

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 73

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 75

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 62

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 63

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 74

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 47

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 50

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 58

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 70

- ↑ Prell 2011, p. 17

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 59

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 61

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 81

- 1 2 3 Prell 2007, p. 136

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 66

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 69

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 85

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 83

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 88

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 90

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 79

- ↑ Grylls 1950, pp. 94–95

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 84

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 103

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 100

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 85

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 110

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 86

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 88

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 89

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 91

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 92

- 1 2 Prell 2011, p. 1

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 114

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 93

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 94

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 117

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 12

- ↑ Voyage from Leghorn to Cephalonia with Lord Byron, by James H. Browne, Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, No. CCXVII. January, 1834, Vol. XXXV, p. 64.

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 95

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 119

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 97

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 98

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 99

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 100

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, p. 149

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 101

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, p. 129

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 102

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, p. 124

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 125

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 103

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 105

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 107

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 108

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 110

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 128

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 113

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 114

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 115

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 116

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 118

- 1 2 3 Grylls 1950, p. 131

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 120

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 121

- ↑ Crane 1999, p. 203

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 122

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, pp. 134–135

- 1 2 3 St Clair 1977, pp. 123–125

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 126

- 1 2 3 4 St Clair 1977, p. 127

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 142

- 1 2 3 Grylls 1950, p. 146

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 129

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 130

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 131

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 132

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 155

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 133

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 134

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 144

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 135

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 136

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 51

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 49

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 137

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 138

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 5

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 140

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 143

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 146

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 148

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 149

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 150

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 151

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 152

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 155

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 156

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 160

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 157

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 158

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 159

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 162

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 163

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 164

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 352

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 165

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 166

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 167

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 168

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 354

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 355

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 169

- ↑ "Additional Light on Trelawny". The New York Times. New York. 4 September 1897. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 358

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 359

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, p. 218

- 1 2 Armstrong 1940, p. 361

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 177

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 175

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 30

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 176

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 217

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 178

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 220

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 179

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 180

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 229

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 183

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 360

- 1 2 Grylls 1950, p. 225

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 367

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 231

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 232

- 1 2 Prell 2008, p. 52

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 228

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 190

- 1 2 St Clair 1977, p. 192

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 193

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 233

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 194

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 195

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 227

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 230

- ↑ St Clair 1977, p. 197

- ↑ Grylls 1950, p. 234

- ↑ Prell 2008, p. 2

- ↑ Bate 1998

Sources

- Armstrong, Margaret (1940), Trelawny, A Man's Life, New York: MacMillan, p. 379

- Bate, Jonathan (4 July 1998), "Keeping up with Byron", The Telegraph, London

- Crane, David (1999), Lord Byron's Jackal: A Life of Edward John Trelawny, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, p. 398

- Grylls, Rosalie Glynn (1950), Trelawny, London: Constable, p. 256

- Langley Moore, Doris (1961), The Late Lord Byron, London: John Murray, p. 533

- Prell, Donald (2007), The Sinking of the Don Juan Revisited, Keats-Shelley Journal, Volume LVI, pp. 138–154

- Prell, Donald (2011), Trelawny Fact or Fiction, Palm Springs: Strand Publishing, pp. 1–61, ISBN 0-9741975-2-1

- Prell, Donald (2010), A Biography of Captain Daniel Roberts, Palm Springs: Strand Publishing, pp. 47–59, ISBN 0-9741975-8-0

- Prell, Donald (2011), Sailing with Byron from Genoa to Cephalonia (1823), Palm Springs: Strand Publishing, pp. 1–20, ISBN 0-9741975-5-6

- St Clair, William (1977), Trelawny, The Incurable Romancer, New York: Vanguard, p. 235, ISBN 0-7195-3424-0

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the Nuttall Encyclopædia article Trelawney, Edward John. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Trelawny, Edward John. |

- Works by Edward John Trelawney at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward John Trelawny at Internet Archive

- The Edward John Trelawny Collection at Clairmont College

- Edward John Trelawny portrait in the National Portrait Gallery

Family tree