Edward Hollamby

| Edward "Ted" Hollamby | |

|---|---|

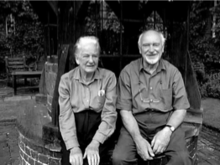

Edward Hollamby (right) and his wife Doris at Red House | |

| Born |

8 January 1921 Hammersmith, West London |

| Died |

29 December 1999 (aged 78) Bexleyheath, Southeast London |

| Spouse(s) | Doris Hollamby (m.1941–1999) |

| Parent(s) |

Ethel May Hollamby Edward Hollamby |

Edward "Ted" Ernest Hollamby OBE (8 January 1921 – 29 December 1999) was an English architect, town planner, and architectural conservationist. Known for designing a number of modernist housing estates in London, he also achieved notability for his work in restoring Red House, the Arts and Crafts building in Bexleyheath, Southeast London which was designed by William Morris and Philip Webb in 1859.

Born in Hammersmith, West London, Hollamby served in the Royal Marines during the Second World War before embarking on a career in architecture. Involved with the Communist Party of Great Britain and other leftist groups, his socialist beliefs led him to work in the public sector, first for the Miners' Welfare Commission and then for London County Council (LCC), where he was involved in the design and construction of such modernist post-war housing estates as Bethnal Green's Avebury Estate, Kennington's Brandon Estate, and Deptford's Pepys Estate.

In 1952, Hollamby and his family moved into the Red House, embarking on projects to renovate and restore it. A great fan of the house's original inhabitant, he also involved himself in the early activities of the William Morris Society, which held a number of meetings at the property. Awarded an OBE for his career in 1970, from 1969 to 1981 Hollamby worked as Director of Architecture, Planning and Development for the London Borough of Lambeth, before moving to work for the London Docklands Development Corporation from 1981 to 1985. He continued restoring Red House in later life, opening it up to visitors and establishing the Friends of Red House charity in 1998.

The Guardian described Hollamby as "very much an architect of the 20th century, a public servant who believed not just in high quality architecture but in the existence and nurturing of the public realm, of public architecture and civic design."[1]

Biography

Early life

Hollamby was born in his parental home of 6 Wellesley Avenue in Hammersmith, West London.[2] He was the oldest of two sons born to Ethel May Hollamby, née Kingdom (1899/1900–1966), and Edward Thomas Hollamby (1893–1978), a police constable.[2] His primary education took place at St. Peter's Church School, before he won a scholarship to study at a junior technical school.[2] From there, he gained a higher education by training in architecture at the nearby Hammersmith School of Arts and Crafts during the 1930s.[3] At the college, he was inspired by the Arts and Crafts aesthetic propounded by one of his lecturers, Alwyn Waters, and through him came to take an interest in William Morris, who had been a pioneer of the Arts and Crafts movement in the latter part of the 19th century. At the same time, Hollamby was influenced by the modernist movement in architecture to which two of his favourite lecturers, Arthur Ling and Alex Lowe, belonged, and joined the Modern Architectural Research Group (MARS).[4]

Following the completion of his studies, he moved to Lancashire to assist a project building the Royal Ordnance factory number 7 in Kirby, before returning to London to work in housing design for the Metropolitan Borough of Hammersmith.[2] On 18 May 1941, he married Doris Isabel Parker (1920–2003), an old friend who worked as a clerk and who, like Hollamby, was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB).[5] Their wedding took place at St Michael's Church at Tokyngton, Middlesex, after which they moved to St. Peter's Square, Hammersmith. They went on to have two daughters and a son.[5] In August 1941, during Britain's involvement in World War II, Hollamby was called up to serve in the British armed forces. Assigned to the Royal Marine Engineers, he served most of the conflict in Trincomalee, Ceylon.[6]

Architectural career

Much like many architects of his generation, following the British victory Hollamby pursued a career in local authority offices.[1] He first worked as an architect for the Miners' Welfare Commission from 1947 to 1949, in this position designing pithead baths and a colliery extension at Lofthouse, Yorkshire.[6] After gaining further qualifications from the Royal Institute of British Architects, he proceeded with a three-year evening course in town planning, run by William Holford and Arthur Ling at the Bartlett School of Architecture, London.[2]

He meanwhile worked under Leslie Martin as a senior architect at the Architects' Department of the London County Council (LCC) from 1949 to 1962. During this period, he oversaw the design of two neighbouring schools in North Hammersmith, now known as the Phoenix School; he unsuccessfully tried to have the school named after Morris. He was also involved in the design and construction of several modernist, high-rise post-war housing estates, namely Bethnal Green's Avebury Estate and Kennington's Brandon Estate, personally securing a sculpture by Henry Moore for the latter. In his final years in this position he focused on estates in south London, working on Deptford's Pepys Estate and the first designs for what became Thamesmead.[6]

From there becoming the borough architect for the Metropolitan Borough of Hammersmith,[7] in January 1963, he moved to become borough architect for the Metropolitan Borough of Lambeth, and following the reorganisation of Greater London he remained in that position for its successor, the London Borough of Lambeth.[2] Here he rose to the position of the borough's director of architecture, planning and development, which he held from 1969 to 1981.[1] In this position he oversaw the construction of several high-rise housing towers alongside an innovative low-rise development at Cressingham Gardens, high-density scheme for Central Hill, as well as a project that combined the construction of new housing with the conservation of old, particularly around Clapham Manor Street.[2] In 1970, Hollamby was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his work in architecture.[8] However, in the early 1980s, he became increasingly unhappy in the position as a result of conflict with certain local Labour Party politicians and sought different employment.[2]

Amid the growing neo-liberal, Thatcherite economic changes brought about under the Premiership of Margaret Thatcher, he moved into the private sector to work for the London Docklands Development Corporation from 1981 to 1985, when he retired. As part of this he took a role in Europe's largest urban regeneration project, proposing a mix of redevelopment and conservation of existing buildings, using this mixed method to create a design guide for the regeneration of the Isle of Dogs. In this position he also campaigned for the Docklands Light Railway and oversaw the exterior refurbishment of St George in the East.[9]

Over the course of his career he also served on the boards of such professional bodies as English Heritage (1986–90), the Historic Buildings Council (1972–82), and the Royal Institute of British Architects (1961–5 and 1966–72).[8]

Red House

In the early 1950s, Hollamby and Doris were living in St. Peter's Square, Hammersmith with two friends, Dick and Mary Toms.[7] Born in London, Richard "Dick" Toms (1914–2005) was largely self-taught as an architect, and had met and befriended Edward during the war before gaining employment alongside him at the LCC.[10] Toms' wife Mary (née Lehner, 1920–2010) was Austrian but had been born in Berlin, Germany. Because her grandfather was Jewish, she fled Austria after it was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938.[10] Both couples were involved in left-wing political activism, being members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the British-Soviet Friendship Society; they were thus sympathetic to the far left political causes to which Morris had devoted much of his later life.[10]

In 1952, the two couples discovered that Red House was up for sale, and as architects with an interest in Morris, they recognised its historic value.[7] By this point, the Red House had been empty for 18 months, after Thomas Hills and his family had left in 1951, and had fallen into a state of dilapidation.[11] Deciding to share the property between themselves, they were able to afford a mortgage with the aid of a loan from Toms' father-in-law; he only agreed to provide the loan if the house was owned in Toms' name, and thus the Hollambys became Toms' tenants.[11] The two families then moved in with their six children, and a seventh was born soon after.[12] They camped in the house's grounds while carrying out a project of renovation.[12]

After being made habitable, the two families divided the house between them, with separate living rooms, bedrooms, bathrooms, and kitchens. Corridors, stairs, and the old kitchen (which they termed the "Eating Room") were shared communally.[12] As a result of their leftist activism, they allowed meetings of both the British-Soviet Friendship Society,[10] and the CPGB to take place in the house.[13] They also permitted members of the Woodcraft Folk to camp in its grounds.[13] In 1953, the inaugural meeting of the William Morris Society took place at the house, at which 45 people were present.[14] In 1954, a third architect, David Gregory Jones, moved into the two rooms adjoining the downstairs gallery.[15]

In 1957, the Toms left Red House and moved to Blackheath, desiring to live closer to central London.[14] They were replaced by Jean and David Macdonald; Jean was an architect colleague of Edward's who shared his socialist values, while David was an accountant and woodworker. Rearranging the former ownership arrangements, the Macdonalds and Hollambys agreed to legally own half of the property each, while Jones remained as a lodger.[16] Together, the two couples made repairs and restorations to the house; they repaired the leaking roof and added Morris & Co. wallpapers along with furniture from Heal's and Ercol.[17] In 1960, the William Morris Society held a garden party there to commemorate the building's centenary.[14] However, in 1964 the Macdonalds left and the Hollambys assumed sole ownership of the House.[16]

Hollamby himself left the Communist Party following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.[2] He remained committed to leftist ideals and involved himself in a number of local socio-political groups, including the local branch of the Labour Party and with his wife was a founding member of Bexley Civic Society.[18] After his retirement in 1985, Hollamby decided to open the Red House up to visitors, offering guided tours on one Sunday per month.[18] As the number of those attending such tours grew, especially in the 1996 centenary of Morris' death, Hollamby began to search for a way of securing future public access. In 1998, he helped to establish the Friends of Red House, a group of individuals who were largely members of the Bexley Civic Society, and who helped to maintain the House and its gardens as well as give tours to visitors.[19] Hollamby also authored two books on Red House; the first, Red House, Bexleyheath: The Home Of William Morris, was published by Phaidon Press in 1991 as part of its series on "Architecture in Detail",[18] and the second was a short guide book for visitors co-written with Doris and published by the William Morris Society in 1993.[20]

Death

Hollamby died suddenly as a result of heart disease at Red House on 29 December 1999; he was the third owner to die while in residence.[21] His funeral was held on 21 January 2000 in Eltham, with a secular humanist service conducted by Barbara Smoker.[7] The Friends of Red House took over the public openings at this point.[22] Amid ill health, Doris left Red House and moved into a care home in 2002; she died in April 2003.[23] With the aid of an anonymous benefactor, the house was purchased and gifted to The National Trust in 2003, who turned it into a visitor's attraction, with tours continuing to be organised by the Friends of Red House.[24]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Glancey 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harwood 2011.

- ↑ Watkinson 2000, p. 6; Youngs 2011, p. 54; Harwood 2011.

- ↑ Watkinson & 2000, p. 6; Harwood 2011.

- 1 2 Glancey 2000; Youngs 2011, p. 55; Harwood 2011.

- 1 2 3 Glancey 2000; Watkinson 2000, p. 6; Youngs 2011, p. 54; Harwood 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Watkinson 2000, p. 6.

- 1 2 Harwood 2011; Youngs 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Glancey 2000; Youngs 2011, pp. 54–55; Harwood 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Youngs 2011, p. 55.

- 1 2 Youngs 2011, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Youngs 2011, p. 54.

- 1 2 Simmons 2000.

- 1 2 3 Youngs 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ Youngs 2011, pp. 53–55.

- 1 2 National Trust 2003, p. 13; Youngs 2011, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ National Trust 2003, p. 13; Youngs 2011, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Youngs 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Youngs 2011, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Hollamby & Hollamby 1993.

- ↑ Watkinson 2000, p. 6; Youngs 2011, p. 59; Harwood 2011.

- ↑ Youngs 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Youngs 2011, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Youngs 2011, p. 60.

Sources

- Glancey, Jonathan (24 January 2000). "Obituary: Edward Hollamby". The Guardian.

- Harwood, Elaine (2011). "Hollamby, Edward Ernest (1921–1999)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Hollamby, Edward; Hollamby, Doris (1993). Red House: A Guide. William Morris Society. ISBN 0-903283-17-4.

- National Trust (2003). Red House. National Trust. ISBN 978-1-84359-088-0.

- Simmons, Michael (10 February 2000). "Appreciation: Edward Hollamby". The Guardian.

- Watkinson, Ray (2000). "Ted Hollamby (1921–1999)" (PDF). The Journal of William Morris Studies. 13 (4): 6–7.

- Youngs, Malcolm (2011). The Later Owners of Red House. Kent: Friends of Red House.

External links

- Friends of Red House page on Ted Hollamby

- British Library: "National Life Story Collection: Architects' Lives" page on Hollamby