Philosophy of education

Philosophy of education can refer either to the application of philosophy to the problem of education, examining definitions, goals and chains of meaning used in education by teachers, administrators and policymakers. It can involve the examination of particular visions or approaches by researchers and policy-makers in education that often address contemporary debates and assumptions about innovations and practices in teaching and learning by considering the profession within broader philosophical or sociocultural contexts.[1]

As an academic field, study involves "the philosophical study of education and its problems...its central subject matter is education, and its methods are those of philosophy".[2] "The philosophy of education may be either the philosophy of the process of education or the philosophy of the discipline of education. That is, it may be part of the discipline in the sense of being concerned with the aims, forms, methods, or results of the process of educating or being educated; or it may be metadisciplinary in the sense of being concerned with the concepts, aims, and methods of the discipline."[3][4] As such, it is both part of the field of education and a field of applied philosophy, drawing from fields of metaphysics, epistemology, axiology and the philosophical approaches (speculative, prescriptive, or analytic) to address questions in and about pedagogy, education policy, and curriculum, as well as the process of learning, to name a few.[5] For example, it might study what constitutes upbringing and education, the values and norms revealed through upbringing and educational practices, the limits and legitimization of education as an academic discipline, and the relation between educational theory and practice. One application is Transactionalism which seeks to avoid the risks of simplifying complexity in teaching and learning any subject.[6]

Instead of being taught in philosophy departments, philosophy of education is usually housed in departments or colleges of education,[7][8][9] similar to how philosophy of law is generally taught in law schools.[2] The multiple ways of conceiving education coupled with the multiple fields and approaches of philosophy make philosophy of education not only a very diverse field but also one that is not easily defined. Although there is overlap, philosophy of education should not be conflated with educational theory, which is not defined specifically by the application of philosophy to questions in education. Philosophy of education also should not be confused with philosophy education, the practice of teaching and learning the subject of philosophy.

Philosophy of education can also be understood not as an academic discipline but as a normative educational theory that unifies pedagogy, curriculum, learning theory, and the purpose of education and is grounded in specific metaphysical, epistemological, and axiological assumptions. These theories are also called educational philosophies. For example, a teacher might be said to follow a perennialist educational philosophy or to follow a perennialist philosophy of education.

Philosophy of education

Idealism

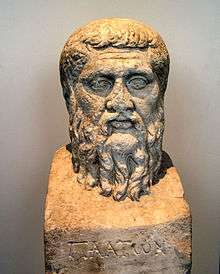

Plato

Date: 424/423 BC – 348/347 BC

Plato's educational philosophy was grounded in a vision of an ideal Republic wherein the individual was best served by being subordinated to a just society due to a shift in emphasis that departed from his predecessors. The mind and body were to be considered separate entiies. In the dialogues of Phaedo, written in his "middle period" (360 B.C.E.) Plato expressed his distinctive views about the nature of knowledge, reality, and the soul:

When the soul and body are united, then nature orders the soul to rule and govern, and the body to obey and serve. Now which of these two functions is akin to the divine? and which to the mortal? Does not the divine appear…to be that which naturally orders and rules, and the mortal to be that which is subject and servant?[10][11]

On this premise, Plato advocated removing children from their mothers' care and raising them as wards of the state, with great care being taken to differentiate children suitable to the various castes, the highest receiving the most education, so that they could act as guardians of the city and care for the less able. Education would be holistic, including facts, skills, physical discipline, and music and art, which he considered the highest form of endeavor.

Plato believed that talent was distributed non-genetically and thus must be found in children born in any social class. He built on this by insisting that those suitably gifted were to be trained by the state so that they might be qualified to assume the role of a ruling class. What this established was essentially a system of selective public education premised on the assumption that an educated minority of the population were, by virtue of their education (and inborn educability), sufficient for healthy governance.

Plato's writings contain some of the following ideas: Elementary education would be confined to the guardian class till the age of 18, followed by two years of compulsory military training and then by higher education for those who qualified. While elementary education made the soul responsive to the environment, higher education helped the soul to search for truth which illuminated it. Both boys and girls receive the same kind of education. Elementary education consisted of music and gymnastics, designed to train and blend gentle and fierce qualities in the individual and create a harmonious person.

At the age of 20, a selection was made. The best students would take an advanced course in mathematics, geometry, astronomy and harmonics. The first course in the scheme of higher education would last for ten years. It would be for those who had a flair for science. At the age of 30 there would be another selection; those who qualified would study dialectics and metaphysics, logic and philosophy for the next five years. After accepting junior positions in the army for 15 years, a man would have completed his theoretical and practical education by the age of 50.

Immanuel Kant

Date: 1724–1804

Immanuel Kant believed that education differs from training in that the former involves thinking whereas the latter does not. In addition to educating reason, of central importance to him was the development of character and teaching of moral maxims. Kant was a proponent of public education and of learning by doing.[12]

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Date: 1770–1831

Realism

Aristotle

Date: 384 BC – 322 BC

Only fragments of Aristotle's treatise On Education are still in existence. We thus know of his philosophy of education primarily through brief passages in other works. Aristotle considered human nature, habit and reason to be equally important forces to be cultivated in education. Thus, for example, he considered repetition to be a key tool to develop good habits. The teacher was to lead the student systematically; this differs, for example, from Socrates' emphasis on questioning his listeners to bring out their own ideas (though the comparison is perhaps incongruous since Socrates was dealing with adults).

Aristotle placed great emphasis on balancing the theoretical and practical aspects of subjects taught. Subjects he explicitly mentions as being important included reading, writing and mathematics; music; physical education; literature and history; and a wide range of sciences. He also mentioned the importance of play.

One of education's primary missions for Aristotle, perhaps its most important, was to produce good and virtuous citizens for the polis. All who have meditated on the art of governing mankind have been convinced that the fate of empires depends on the education of youth.[13]

Avicenna

Date: 980 AD – 1037 AD

In the medieval Islamic world, an elementary school was known as a maktab, which dates back to at least the 10th century. Like madrasahs (which referred to higher education), a maktab was often attached to a mosque. In the 11th century, Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West), wrote a chapter dealing with the maktab entitled "The Role of the Teacher in the Training and Upbringing of Children", as a guide to teachers working at maktab schools. He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates. Ibn Sina described the curriculum of a maktab school in some detail, describing the curricula for two stages of education in a maktab school.[14]

Ibn Sina wrote that children should be sent to a maktab school from the age of 6 and be taught primary education until they reach the age of 14. During which time, he wrote that they should be taught the Qur'an, Islamic metaphysics, language, literature, Islamic ethics, and manual skills (which could refer to a variety of practical skills).[14]

Ibn Sina refers to the secondary education stage of maktab schooling as the period of specialization, when pupils should begin to acquire manual skills, regardless of their social status. He writes that children after the age of 14 should be given a choice to choose and specialize in subjects they have an interest in, whether it was reading, manual skills, literature, preaching, medicine, geometry, trade and commerce, craftsmanship, or any other subject or profession they would be interested in pursuing for a future career. He wrote that this was a transitional stage and that there needs to be flexibility regarding the age in which pupils graduate, as the student's emotional development and chosen subjects need to be taken into account.[15]

The empiricist theory of 'tabula rasa' was also developed by Ibn Sina. He argued that the "human intellect at birth is rather like a tabula rasa, a pure potentiality that is actualized through education and comes to know" and that knowledge is attained through "empirical familiarity with objects in this world from which one abstracts universal concepts" which is developed through a "syllogistic method of reasoning; observations lead to prepositional statements, which when compounded lead to further abstract concepts." He further argued that the intellect itself "possesses levels of development from the material intellect (al-‘aql al-hayulani), that potentiality that can acquire knowledge to the active intellect (al-‘aql al-fa‘il), the state of the human intellect in conjunction with the perfect source of knowledge."[16]

Ibn Tufail

Date: c. 1105 – 1185

In the 12th century, the Andalusian-Arabian philosopher and novelist Ibn Tufail (known as "Abubacer" or "Ebn Tophail" in the West) demonstrated the empiricist theory of 'tabula rasa' as a thought experiment through his Arabic philosophical novel, Hayy ibn Yaqzan, in which he depicted the development of the mind of a feral child "from a tabula rasa to that of an adult, in complete isolation from society" on a desert island, through experience alone. The Latin translation of his philosophical novel, Philosophus Autodidactus, published by Edward Pococke the Younger in 1671, had an influence on John Locke's formulation of tabula rasa in "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding".[17]

John Locke

Date: 1632–1704

In Some Thoughts Concerning Education and Of the Conduct of the Understanding Locke composed an outline on how to educate this mind in order to increase its powers and activity:

"The business of education is not, as I think, to make them perfect in any one of the sciences, but so to open and dispose their minds as may best make them capable of any, when they shall apply themselves to it."[18]

"If men are for a long time accustomed only to one sort or method of thoughts, their minds grow stiff in it, and do not readily turn to another. It is therefore to give them this freedom, that I think they should be made to look into all sorts of knowledge, and exercise their understandings in so wide a variety and stock of knowledge. But I do not propose it as a variety and stock of knowledge, but a variety and freedom of thinking, as an increase of the powers and activity of the mind, not as an enlargement of its possessions."[19]

Locke expressed the belief that education maketh the man, or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty cabinet", with the statement, "I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education."[20]

Locke also wrote that "the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences."[21] He argued that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self: they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which is introduced both of these concepts, Locke warns against, for example, letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other."[22]

"Associationism", as this theory would come to be called, exerted a powerful influence over eighteenth-century thought, particularly educational theory, as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

.jpg)

Date: 1712–1778

Rousseau, though he paid his respects to Plato's philosophy, rejected it as impractical due to the decayed state of society. Rousseau also had a different theory of human development; where Plato held that people are born with skills appropriate to different castes (though he did not regard these skills as being inherited), Rousseau held that there was one developmental process common to all humans. This was an intrinsic, natural process, of which the primary behavioral manifestation was curiosity. This differed from Locke's 'tabula rasa' in that it was an active process deriving from the child's nature, which drove the child to learn and adapt to its surroundings.

Rousseau wrote in his book Emile that all children are perfectly designed organisms, ready to learn from their surroundings so as to grow into virtuous adults, but due to the malign influence of corrupt society, they often fail to do so. Rousseau advocated an educational method which consisted of removing the child from society—for example, to a country home—and alternately conditioning him through changes to his environment and setting traps and puzzles for him to solve or overcome.

Rousseau was unusual in that he recognized and addressed the potential of a problem of legitimation for teaching. He advocated that adults always be truthful with children, and in particular that they never hide the fact that the basis for their authority in teaching was purely one of physical coercion: "I'm bigger than you." Once children reached the age of reason, at about 12, they would be engaged as free individuals in the ongoing process of their own.

He once said that a child should grow up without adult interference and that the child must be guided to suffer from the experience of the natural consequences of his own acts or behaviour. When he experiences the consequences of his own acts, he advises himself.

"Rousseau divides development into five stages (a book is devoted to each). Education in the first two stages seeks to the senses: only when Émile is about 12 does the tutor begin to work to develop his mind. Later, in Book 5, Rousseau examines the education of Sophie (whom Émile is to marry). Here he sets out what he sees as the essential differences that flow from sex. 'The man should be strong and active; the woman should be weak and passive' (Everyman edn: 322). From this difference comes a contrasting education. They are not to be brought up in ignorance and kept to housework: Nature means them to think, to will, to love to cultivate their minds as well as their persons; she puts these weapons in their hands to make up for their lack of strength and to enable them to direct the strength of men. They should learn many things, but only such things as suitable' (Everyman edn.: 327)." Émile

Mortimer Jerome Adler

Date: 1902–2001

Mortimer Jerome Adler was an American philosopher, educator, and popular author. As a philosopher he worked within the Aristotelian and Thomistic traditions. He lived for the longest stretches in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, and San Mateo, California. He worked for Columbia University, the University of Chicago, Encyclopædia Britannica, and Adler's own Institute for Philosophical Research. Adler was married twice and had four children.[23] Adler was a proponent of educational perennialism.

Harry S. Broudy

Date: 1905–1998

Broudy's philosophical views were based on the tradition of classical realism, dealing with truth, goodness, and beauty. However he was also influenced by the modern philosophy existentialism and instrumentalism. In his textbook Building a Philosophy of Education he has two major ideas that are the main points to his philosophical outlook: The first is truth and the second is universal structures to be found in humanity's struggle for education and the good life. Broudy also studied issues on society's demands on school. He thought education would be a link to unify the diverse society and urged the society to put more trust and a commitment to the schools and a good education.

Scholasticism

Thomas Aquinas

Date: c. 1225 – 1274

John Milton

Date: 1608–1674

The objective of medieval education was an overtly religious one, primarily concerned with uncovering transcendental truths that would lead a person back to God through a life of moral and religious choice (Kreeft 15). The vehicle by which these truths were uncovered was dialectic:

To the medieval mind, debate was a fine art, a serious science, and a fascinating entertainment, much more than it is to the modern mind, because the medievals believed, like Socrates, that dialectic could uncover truth. Thus a 'scholastic disputation' was not a personal contest in cleverness, nor was it 'sharing opinions'; it was a shared journey of discovery (Kreeft 14–15).

Pragmatism

John Dewey

Date: 1859–1952

In Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, Dewey stated that education, in its broadest sense, is the means of the "social continuity of life" given the "primary ineluctable facts of the birth and death of each one of the constituent members in a social group". Education is therefore a necessity, for "the life of the group goes on."[24] Dewey was a proponent of Educational Progressivism and was a relentless campaigner for reform of education, pointing out that the authoritarian, strict, pre-ordained knowledge approach of modern traditional education was too concerned with delivering knowledge, and not enough with understanding students' actual experiences.[25]

William James

Date: 1842–1910

William Heard Kilpatrick

Date: 1871–1965

William Heard Kilpatrick was a US American philosopher of education and a colleague and a successor of John Dewey. He was a major figure in the progressive education movement of the early 20th century. Kilpatrick developed the Project Method for early childhood education, which was a form of Progressive Education organized curriculum and classroom activities around a subject's central theme. He believed that the role of a teacher should be that of a "guide" as opposed to an authoritarian figure. Kilpatrick believed that children should direct their own learning according to their interests and should be allowed to explore their environment, experiencing their learning through the natural senses.[26] Proponents of Progressive Education and the Project Method reject traditional schooling that focuses on memorization, rote learning, strictly organized classrooms (desks in rows; students always seated), and typical forms of assessment.

Nel Noddings

Date: 1929–

Noddings' first sole-authored book Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education (1984) followed close on the 1982 publication of Carol Gilligan’s ground-breaking work in the ethics of care In a Different Voice. While her work on ethics continued, with the publication of Women and Evil (1989) and later works on moral education, most of her later publications have been on the philosophy of education and educational theory. Her most significant works in these areas have been Educating for Intelligent Belief or Unbelief (1993) and Philosophy of Education (1995).

Richard Rorty

Date: 1931–2007

Analytic philosophy

G.E Moore (1873–1858)

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970)

Gottlob Frege (1848–1925)

Richard Stanley Peters (1919–2011)

Date: 1919–

Existentialist

The existentialist sees the world as one's personal subjectivity, where goodness, truth, and reality are individually defined. Reality is a world of existing, truth subjectively chosen, and goodness a matter of freedom. The subject matter of existentialist classrooms should be a matter of personal choice. Teachers view the individual as an entity within a social context in which the learner must confront others' views to clarify his or her own. Character development emphasizes individual responsibility for decisions. Real answers come from within the individual, not from outside authority. Examining life through authentic thinking involves students in genuine learning experiences. Existentialists are opposed to thinking about students as objects to be measured, tracked, or standardized. Such educators want the educational experience to focus on creating opportunities for self-direction and self-actualization. They start with the student, rather than on curriculum content.

Critical theory

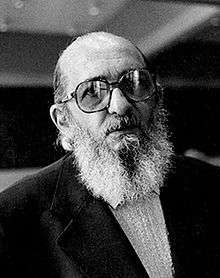

Paulo Freire

Date: 1921–1997

A Brazilian philosopher and educator committed to the cause of educating the impoverished peasants of his nation and collaborating with them in the pursuit of their liberation from what he regarded as "oppression," Freire is best known for his attack on what he called the "banking concept of education," in which the student was viewed as an empty account to be filled by the teacher. Freire also suggests that a deep reciprocity be inserted into our notions of teacher and student; he comes close to suggesting that the teacher-student dichotomy be completely abolished, instead promoting the roles of the participants in the classroom as the teacher-student (a teacher who learns) and the student-teacher (a learner who teaches). In its early, strong form this kind of classroom has sometimes been criticized on the grounds that it can mask rather than overcome the teacher's authority.

Aspects of the Freirian philosophy have been highly influential in academic debates over "participatory development" and development more generally. Freire's emphasis on what he describes as "emancipation" through interactive participation has been used as a rationale for the participatory focus of development, as it is held that 'participation' in any form can lead to empowerment of poor or marginalised groups. Freire was a proponent of critical pedagogy. "He participated in the import of European doctrines and ideas into Brazil, assimilated them to the needs of a specific socio-economic situation, and thus expanded and refocused them in a thought-provoking way"

Other Continental thinkers

Martin Heidegger

Date: 1889–1976

Heidegger's philosophizing about education was primarily related to higher education. He believed that teaching and research in the university should be unified and aim towards testing and interrogating the "ontological assumptions presuppositions which implicitly guide research in each domain of knowledge."[27]

Hans-Georg Gadamer

Date: 1900–2002

Jean-François Lyotard

Date: 1924–1998

Michel Foucault

Date: 1926–1984

Normative educational philosophies

"Normative philosophies or theories of education may make use of the results of philosophical thought and of factual inquiries about human beings and the psychology of learning, but in any case they propound views about what education should be, what dispositions it should cultivate, why it ought to cultivate them, how and in whom it should do so, and what forms it should take. In a full-fledged philosophical normative theory of education, besides analysis of the sorts described, there will normally be propositions of the following kinds:

- Basic normative premises about what is good or right;

- Basic factual premises about humanity and the world;

- Conclusions, based on these two kinds of premises, about the dispositions education should foster;

- Further factual premises about such things as the psychology of learning and methods of teaching; and

- Further conclusions about such things as the methods that education should use."[3]

Perennialism

Perennialists believe that one should teach the things that one deems to be of everlasting importance to all people everywhere. They believe that the most important topics develop a person. Since details of fact change constantly, these cannot be the most important. Therefore, one should teach principles, not facts. Since people are human, one should teach first about humans, not machines or techniques. Since people are people first, and workers second if at all, one should teach liberal topics first, not vocational topics. The focus is primarily on teaching reasoning and wisdom rather than facts, the liberal arts rather than vocational training.

Allan Bloom

Date: 1930–1992

Bloom, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, argued for a traditional Great Books-based liberal education in his lengthy essay The Closing of the American Mind.

Classical education

The Classical education movement advocates a form of education based in the traditions of Western culture, with a particular focus on education as understood and taught in the Middle Ages. The term "classical education" has been used in English for several centuries, with each era modifying the definition and adding its own selection of topics. By the end of the 18th century, in addition to the trivium and quadrivium of the Middle Ages, the definition of a classical education embraced study of literature, poetry, drama, philosophy, history, art, and languages. In the 20th and 21st centuries it is used to refer to a broad-based study of the liberal arts and sciences, as opposed to a practical or pre-professional program. Classical Education can be described as rigorous and systematic, separating children and their learning into three rigid categories, Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric.

Charlotte Mason

Date: 1842–1923

Mason was a British educator who invested her life in improving the quality of children's education. Her ideas led to a method used by some homeschoolers. Mason's philosophy of education is probably best summarized by the principles given at the beginning of each of her books. Two key mottos taken from those principles are "Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life" and "Education is the science of relations." She believed that children were born persons and should be respected as such; they should also be taught the Way of the Will and the Way of Reason. Her motto for students was "I am, I can, I ought, I will." Charlotte Mason believed that children should be introduced to subjects through living books, not through the use of "compendiums, abstracts, or selections." She used abridged books only when the content was deemed inappropriate for children. She preferred that parents or teachers read aloud those texts (such as Plutarch and the Old Testament), making omissions only where necessary.

Essentialism

Educational essentialism is an educational philosophy whose adherents believe that children should learn the traditional basic subjects and that these should be learned thoroughly and rigorously. An essentialist program normally teaches children progressively, from less complex skills to more complex.

William Chandler Bagley

Date: 1874–1946

William Chandler Bagley taught in elementary schools before becoming a professor of education at the University of Illinois, where he served as the Director of the School of Education from 1908 until 1917. He was a professor of education at Teachers College, Columbia, from 1917 to 1940. An opponent of pragmatism and progressive education, Bagley insisted on the value of knowledge for its own sake, not merely as an instrument, and he criticized his colleagues for their failure to emphasize systematic study of academic subjects. Bagley was a proponent of educational essentialism.

Social reconstructionism and critical pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is an "educational movement, guided by passion and principle, to help students develop consciousness of freedom, recognize authoritarian tendencies, and connect knowledge to power and the ability to take constructive action." Based in Marxist theory, critical pedagogy draws on radical democracy, anarchism, feminism, and other movements for social justice.

George Counts

Date: 1889–1974

Maria Montessori

Date: 1870–1952

The Montessori method arose from Dr. Maria Montessori's discovery of what she referred to as "the child's true normal nature" in 1907,[28] which happened in the process of her experimental observation of young children given freedom in an environment prepared with materials designed for their self-directed learning activity.[29] The method itself aims to duplicate this experimental observation of children to bring about, sustain and support their true natural way of being.[30]

Waldorf

Waldorf education (also known as Steiner or Steiner-Waldorf education) is a humanistic approach to pedagogy based upon the educational philosophy of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Learning is interdisciplinary, integrating practical, artistic, and conceptual elements. The approach emphasizes the role of the imagination in learning, developing thinking that includes a creative as well as an analytic component. The educational philosophy's overarching goals are to provide young people the basis on which to develop into free, morally responsible and integrated individuals, and to help every child fulfill his or her unique destiny, the existence of which anthroposophy posits. Schools and teachers are given considerable freedom to define curricula within collegial structures.

Rudolf Steiner

Date: 1861–1925

Steiner founded a holistic educational impulse on the basis of his spiritual philosophy (anthroposophy). Now known as Steiner or Waldorf education, his pedagogy emphasizes a balanced development of cognitive, affective/artistic, and practical skills (head, heart, and hands). Schools are normally self-administered by faculty; emphasis is placed upon giving individual teachers the freedom to develop creative methods.

Steiner's theory of child development divides education into three discrete developmental stages predating but with close similarities to the stages of development described by Piaget. Early childhood education occurs through imitation; teachers provide practical activities and a healthy environment. Steiner believed that young children should meet only goodness. Elementary education is strongly arts-based, centered on the teacher's creative authority; the elementary school-age child should meet beauty. Secondary education seeks to develop the judgment, intellect, and practical idealism; the adolescent should meet truth.

Democratic education

Democratic education is a theory of learning and school governance in which students and staff participate freely and equally in a school democracy. In a democratic school, there is typically shared decision-making among students and staff on matters concerning living, working, and learning together.

A. S. Neill

Date: 1883–1973

Neill founded Summerhill School, the oldest existing democratic school in Suffolk, England in 1921. He wrote a number of books that now define much of contemporary democratic education philosophy. Neill believed that the happiness of the child should be the paramount consideration in decisions about the child's upbringing, and that this happiness grew from a sense of personal freedom. He felt that deprivation of this sense of freedom during childhood, and the consequent unhappiness experienced by the repressed child, was responsible for many of the psychological disorders of adulthood.

Progressivism

Educational progressivism is the belief that education must be based on the principle that humans are social animals who learn best in real-life activities with other people. Progressivists, like proponents of most educational theories, claim to rely on the best available scientific theories of learning. Most progressive educators believe that children learn as if they were scientists, following a process similar to John Dewey's model of learning known as "the pattern of inquiry":[31] 1) Become aware of the problem. 2) Define the problem. 3) Propose hypotheses to solve it. 4) Evaluate the consequences of the hypotheses from one's past experience. 5) Test the likeliest solution.

John Dewey

Date: 1859–1952

In 1896, Dewey opened the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago in an institutional effort to pursue together rather than apart "utility and culture, absorption and expression, theory and practice, [which] are [indispensable] elements in any educational scheme.[32] As the unified head of the departments of Philosophy, Psychology and Pedagogy, John Dewey articulated a desire to organize an educational experience where children could be more creative than the best of progressive models of his day.[33] Transactionalism as a pragmatic philosophy grew out of the work he did in the Laboratory School. The two most influential works that stemmed from his research and study were The Child and the Curriculum (1902) and Democracy and Education (1916).[34] Dewey wrote of the dualisms that plagued educational philosophy in the latter book: "Instead of seeing the educative process steadily and as a whole, we see conflicting terms. We get the case of the child vs. the curriculum; of the individual nature vs. social culture."[35] Dewey found that the preoccupation with facts as knowledge in the educative process led students to memorize "ill-understood rules and principles" and while second-hand knowledge learned in mere words is a beginning in study, mere words can never replace the ability to organize knowledge into both useful and valuable experience.[36]

Jean Piaget

Date: 1896–1980

Jean Piaget was a Swiss developmental psychologist known for his epistemological studies with children. His theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology". Piaget placed great importance on the education of children. As the Director of the International Bureau of Education, he declared in 1934 that "only education is capable of saving our societies from possible collapse, whether violent, or gradual."[37] Piaget created the International Centre for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva in 1955 and directed it until 1980. According to Ernst von Glasersfeld, Jean Piaget is "the great pioneer of the constructivist theory of knowing."[38]

Jean Piaget described himself as an epistemologist, interested in the process of the qualitative development of knowledge. As he says in the introduction of his book "Genetic Epistemology" (ISBN 978-0-393-00596-7): "What the genetic epistemology proposes is discovering the roots of the different varieties of knowledge, since its elementary forms, following to the next levels, including also the scientific knowledge."

Jerome Bruner

Date: 1915–2016

Another important contributor to the inquiry method in education is Bruner. His books The Process of Education and Toward a Theory of Instruction are landmarks in conceptualizing learning and curriculum development. He argued that any subject can be taught in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development. This notion was an underpinning for his concept of the spiral curriculum which posited the idea that a curriculum should revisit basic ideas, building on them until the student had grasped the full formal concept. He emphasized intuition as a neglected but essential feature of productive thinking. He felt that interest in the material being learned was the best stimulus for learning rather than external motivation such as grades. Bruner developed the concept of discovery learning which promoted learning as a process of constructing new ideas based on current or past knowledge. Students are encouraged to discover facts and relationships and continually build on what they already know.

Unschooling

Unschooling is a range of educational philosophies and practices centered on allowing children to learn through their natural life experiences, including child directed play, game play, household responsibilities, work experience, and social interaction, rather than through a more traditional school curriculum. Unschooling encourages exploration of activities led by the children themselves, facilitated by the adults. Unschooling differs from conventional schooling principally in the thesis that standard curricula and conventional grading methods, as well as other features of traditional schooling, are counterproductive to the goal of maximizing the education of each child.

John Holt

In 1964 Holt published his first book, How Children Fail, asserting that the academic failure of schoolchildren was not despite the efforts of the schools, but actually because of the schools. Not surprisingly, How Children Fail ignited a firestorm of controversy. Holt was catapulted into the American national consciousness to the extent that he made appearances on major TV talk shows, wrote book reviews for Life magazine, and was a guest on the To Tell The Truth TV game show.[39] In his follow-up work, How Children Learn, published in 1967, Holt tried to elucidate the learning process of children and why he believed school short circuits that process.

Contemplative education

Contemplative education focuses on bringing introspective practices such as mindfulness and yoga into curricular and pedagogical processes for diverse aims grounded in secular, spiritual, religious and post-secular perspectives.[40][41] Contemplative approaches may be used in the classroom, especially in tertiary or (often in modified form) in secondary education. Parker Palmer is a recent pioneer in contemplative methods. The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society founded a branch focusing on education, The Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education.

Contemplative methods may also be used by teachers in their preparation; Waldorf education was one of the pioneers of the latter approach. In this case, inspiration for enriching the content, format, or teaching methods may be sought through various practices, such as consciously reviewing the previous day's activities; actively holding the students in consciousness; and contemplating inspiring pedagogical texts. Zigler suggested that only through focusing on their own spiritual development could teachers positively impact the spiritual development of students.[42]

Professional organizations and associations

| Organisation | Nationality | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| International Network of Philosophers of Education | Worldwide | INPE is dedicated to fostering dialogue amongst philosophers of education around the world. It sponsors an international conference every other year. |

| Philosophy of Education Society | USA | PES is the national society for philosophy of education in the United States of America. This site provides information about PES, its services, history, and publications, and links to online resources relevant to the philosophy of education. |

| Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain | UK | PESGB promotes the study, teaching and application of philosophy of education. It has an international membership. The site provides: a guide to the Society's activities and details about the Journal of Philosophy of Education and IMPACT. |

| Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia | Australasia | PESA promotes research and teaching in philosophy of education. It has a broad membership across not just Australia and New Zealand but also Asia, Europe and North America. PESA adopts an inclusive approach to philosophical work in education, and welcome contributions to the life of the Society from a variety of different theoretical traditions and perspectives. |

| Canadian Philosophy of Education Society | Canada | CPES is devoted to philosophical inquiry into educational issues and their relevance for developing educative, caring, and just teachers, schools, and communities. The society welcomes inquiries about membership from professionals and graduate students who share these interests. |

| The Nordic Society for Philosophy of Education | The Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden | The Nordic Society for Philosophy of Education is a society consisting of Nordic philosophers of education with the purpose of fostering dialogue among philosophers of education within and beyond the Nordic countries, and to coordinate, facilitate and support exchange of ideas, information and experiences. |

| Society for the Philosophical Study of Education | USA | This Society is a professional association of philosophers of education which holds annual meetings in the Midwest region of the United States of America and sponsors a discussion forum and a Graduate Student Competition. Affiliate of the American Philosophical Association. |

| Ohio Valley Philosophy of Education Society | USA, Ohio Valley | OVPES is a professional association of philosophers of education. We host an annual conference in the Ohio Valley region of the United States of America and sponsor a refereed journal: Philosophical Studies in Education. |

| John Dewey Society | USA | The John Dewey Society exists to keep alive John Dewey's commitment to the use of critical and reflective intelligence in the search for solutions to crucial problems in education and culture. |

| StudyPlace for Philosophy of Education | USA, Columbia University | This study place exists for persons who wish to engage in philosophy and education because both have value for them, quite apart from their professional responsibilities. We think networked digital information resources will enable people to reverse this ever-narrowing professionalism. This site is maintained at the Institute for Learning Technologies, Teachers College, Columbia University. |

| Center for Dewey Studies | USA, Southern Illinois University | The Center for Dewey Studies at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale was established in 1961 as the "Dewey Project." By virtue of its publications and research, the Center has become the international focal point for research on John Dewey's life and work. |

| International Society for Philosophy of Music Education | Unknown | the International Society for the Philosophy of Music Education (ISPME) is founded on both educational and professional objectives: "devoted to the specific interests of philosophy of music education in elementary through secondary schools, colleges and universities, in private studios, places of worship, and all the other places and ways in which music is taught and learned."[43] |

| The Spencer Foundation | USA | The Spencer Foundation provides funding for investigations that promise to yield new knowledge about education in the United States or abroad. The Foundation funds research grants that range in size from smaller grants that can be completed within a year, to larger, multi-year endeavours. |

| Humanities Research Network | New Zealand | The Humanities Research Network is designed to encourage new ways of thinking about the overlapping domains of knowledge which are represented by the arts, humanities, social sciences, other related fields like law, and matauranga Māori, and new relationships among their practitioners. |

See also

References

- ↑ "SHIPS - Philosophy | Stanford Graduate School of Education". ed.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- 1 2 Noddings, Nel (1995). Philosophy of Education. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-8133-8429-X

- 1 2 Frankena, William K.; Raybeck, Nathan; Burbules, Nicholas (2002). "Philosophy of Education". In Guthrie, James W. Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 0-02-865594-X

- ↑ Phillips, Trevor J. (2017-03-18). "Ch. III: Transactionalism in Contemporary Philosophy and Ch. V: The Educative Process". In Tibbels, Kirkland; Patterson, John. Transactionalism: An Historical and Interpretive Study. Independently published. pp. 163–205. ISBN 9781520829319.

- ↑ Noddings 1995, pp. 1–6

- ↑ Mason, Mark (2008-02-01). "Complexity Theory and the Philosophy of Education". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 40 (1): 4–18. ISSN 1469-5812. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00412.x.

- ↑ "Philosophy and Education". Teachers College - Columbia University. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "Philosophy of Education - Courses - NYU Steinhardt". steinhardt.nyu.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "Doctor of Philosophy in Education". Harvard Graduate School of Education. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "Plato: Phaedo | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". www.iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "The Internet Classics Archive | Phaedo by Plato". classics.mit.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ Cahn, Steven M. (1997). Classic and Contemporary Readings in the Philosophy of Education. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. p. 197. ISBN 0-07-009619-8.

- ↑

- 1 2 M. S. Asimov, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1999). The Age of Achievement: Vol 4. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 33–4. ISBN 81-208-1596-3

- ↑ M. S. Asimov, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1999). The Age of Achievement: Vol 4. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 34–5. ISBN 81-208-1596-3

- ↑ Sajjad H. Rizvi (2006), Avicenna/Ibn Sina (CA. 980-1037), Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ G. A. Russell (1994), The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, pp. 224-262, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- ↑ Locke, John (1764). Locke's Conduct of the understanding; edited with introd., notes, etc. by Thomas Fowler. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 44.

- ↑ Locke, John (1764). Locke's Conduct of the understanding; edited with introd., notes, etc. by Thomas Fowler. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Locke, John. Some Thoughts Concerning Education and Of the Conduct of the Understanding. Eds. Ruth W. Grant and Nathan Tarcov. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., Inc. (1996), p. 10.

- ↑ Locke, Some Thoughts, 10.

- ↑ Locke, Essay, 357.

- ↑ William Grimes, "Mortimer Adler, 98, Dies; Helped Create Study of Classics," New York Times, June 29, 2001

- ↑ "Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ↑ Neil, J. (2005) John Dewey, the Modern Father of Experiential Education. Wilderdom.com. Retrieved 6/12/07.

- ↑ Gutek, Gerald L. (2009). New Perspectives on Philosophy and Education. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 346. ISBN 0-205-59433-6.

- ↑ Thomson, Iain (2002). "Heidegger on Ontological Education"". In Peters, Michael A. Heidegger, Education, and Modernity. New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield. pp. 141–142. ISBN 0-7425-0887-0

- ↑ Maria Montessori: Her Life And Work, E.M. Standing, p. 174, Publ. Plume, 1998, http://www.penguinputnam.com

- ↑ The Montessori Method, Maria Montessori, pp. 79–81, Publ. Random House, 1988, http://www.randomhouse.com

- ↑ Discovery of the Child, Maria Montessori, p.46, Publ. Ballantine Books, 1972, http://www.randomhouse.com

- ↑ Dewey, John (1938). Logic, the theory of inquiry. New York, H. Holt and Company.

- ↑ Dewey, John (1904). "Significance of the School of Education". The Elementary School Teacher. 4 (7): 441–453.

- ↑ "Full text of "The Dewey School The Laboratory School Of The University Of Chicago 1896-1903"". www.archive.org. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Phillips, Trevor J. (2015-11-22). Tibbels, Kirkland; Patterson, John, eds. Transactionalism: An Historical and Interpretive Study (2 edition ed.). Influence Ecology. p. 166.

- ↑ Phillips, Trevor J. (2015-11-22). Tibbels, Kirkland; Patterson, John, eds. Transactionalism: An Historical and Interpretive Study (2 edition ed.). Influence Ecology. p. 167.

- ↑ Phillips, Trevor J. (2015-11-22). Tibbels, Kirkland; Patterson, John, eds. Transactionalism: An Historical and Interpretive Study (2 edition ed.). Influence Ecology. pp. 171–2.

- ↑ "International Bureau of Education - Directors" <http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9059885>. Munari, Alberto (1994). "JEAN PIAGET (1896–1980)" (PDF). Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education. XXIV (1/2): 311–327. doi:10.1007/bf02199023.

- ↑ (in An Exposition of Constructivism: Why Some Like it Radical, 1990)

- ↑ The Old Schoolhouse Meets Up with Patrick Farenga About the Legacy of John Holt, http://www.thehomeschoolmagazine.com/How_To_Homeschool/articles/articles.php?aid=97

- ↑ Lewin, David (2016). Educational philosophy for a post-secular age.

- ↑ Ergas, Oren (13 December 2013). "Mindfulness in education at the intersection of science, religion, and healing". Critical Studies in Education. 55 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1080/17508487.2014.858643.

- ↑ Zigler, Ronald Lee (1999). "Tacit Knowledge and Spiritual Pedagogy". Journal of Beliefs & Values: Studies in Religion and Education. 20 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1080/1361767990200202.

- ↑ "ISPME Home". Retrieved 12 November 2010.

Further reading

- Classic and Contemporary Readings in the Philosophy of Education, by Steven M. Cahn, 1997, ISBN 978-0-07-009619-6

- A Companion to the Philosophy of Education (Blackwell Companions to Philosophy), ed. by Randall Curren, Paperback edition, 2006, ISBN 1-4051-4051-8

- The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Education, ed. by Nigel Blake, Paul Smeyers, Richard Smith, and Paul Standish, Paperback edition, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22119-0

- Philosophy of Education (Westview Press, Dimension of Philosophy Series), by Nel Noddings, Paperback edition, 1995, ISBN 0-8133-8430-3

- The quarterly review of comparative education: Aristotle

- Andre Kraak,Michael Young Education in Retrospect: Policy And Implementation Since 1990

- Freire, UNESCO publication

External links

| Library resources about Philosophy of education |

- "Philosophy of Education". In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Education

- Thinkers of Education. UNESCO-International Bureau of Education website

- International Society for Philosophy of Music Education

- International Network of Philosophers of Education

- Philosophy of Education Society

- Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain

- Philosophy of Education Society of Australia

- Canadian Philosophy of Education Society (CPES)

- The Nordic Society for Philosophy of Education

- Society for the Philosophical Study of Education

- The Ohio Valley Philosophy of Education Society

- Humanities Research Network; Te Whatunga Rangahau Aronu

- Leaders Educational Advise