Edmond Malone

| Edmond Malone | |

|---|---|

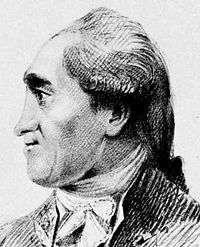

Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait in oil of Edmond Malone. | |

| Born |

4 October 1741 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

25 May 1812 (aged 70) London, England |

| Occupation | Lawyer, historian |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Edmond Malone (4 October 1741 – 25 May 1812) was an Irish Shakespearean scholar and editor of the works of William Shakespeare.

Assured of an income after the death of his father in 1774, Malone was able to give up his law practice for at first political and then more congenial literary pursuits. He went to London, where he frequented literary and artistic circles. He regularly visited Samuel Johnson and was of great assistance to James Boswell in revising and proofreading his Life, four of the later editions of which he annotated. He was friendly with Sir Joshua Reynolds, and sat for a portrait now in the National Portrait Gallery.

He was one of Reynolds' executors, and published a posthumous collection of his works (1798) with a memoir. Horace Walpole, Edmund Burke, George Canning, Oliver Goldsmith, Lord Charlemont, and, at first, George Steevens, were among Malone's friends. Encouraged by Charlemont and Steevens, he devoted himself to the study of Shakespearean chronology, and the results of his "An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in Which the Plays Attributed to Shakspeare Were Written" (1778), which finally made it conceivable to try to patch together a biography of Shakespeare through the plays themselves,[1] are still largely accepted. This was followed in 1780 by two supplementary volumes to Steevens's version of Dr Johnson's Shakespeare, partly consisting of observations on the history of the Elizabethan stage, and of the text of doubtful plays; and this again, in 1783, by an appendix volume. His refusal to alter some of his notes to Isaac Reed's edition of 1785, which disagreed with Steevens's, resulted in a quarrel with the latter. Malone was also a central figure in the refutation of the claim that the Ireland Shakespeare forgeries were authentic works of the playwright, which many contemporary academics had believed.

Biography

Birth and early life

Edmond Malone was born 4 October 1741 in Dublin to Edmond Malone Sr. (1704–1774) —MP of the Irish House of Commons and judge of the Court of Common Pleas in Ireland—and Catherine Collier, the niece of Robert Knight, 1st Earl of Catherlough. He had two sisters, Henrietta and Catherine, and an older brother, Richard (later Lord Sunderlin). Edmond Malone Sr. was a successful lawyer and politician, educated at Oxford University and the Inner Temple in London, and called to the Bar in England in 1730, where he had a legal practice. But in 1740, a year before Edmond Jr. was born, his practice in England failed and he returned to Ireland. He took up residence with his wife on the family's country estate, Shinglas, in County Westmeath, and began a more successful legal practice there.[2]

According to Peter Martin, Malone's main biographer in the 20th century: “Virtually nothing is known of his childhood and adolescence except that in 1747 he was sent to Dr. Ford's preparatory school in Molesworth Street, Dublin, where his brother Richard had already been enrolled for two years.”[3] The next record of his education is 10 years later, in 1757, when he—not yet 16 years old—entered Trinity College, Dublin, where his brother went to study two years earlier and where his father had received an honorary LL.D. the year before. Malone excelled at his studies, "an exemplary student, naturally diligent, consistently at the top of his class",[3] and was awarded with books stamped with the College Arms. In the very first examination, of four in the academic year, he shared top honours with James Drought and John Kearney, who later became Fellows of the College.[2]

| “ | …the Antient Chorus … has been entirely rejected by all the modern tragick writers … few but those who converse more with the dead than the living, have any ideas of its use & advantages. | ” |

| — Edmond Malone, given in Martin (2005: pp.2–3)[4] | ||

As an undergraduate he wrote some poetry and literary history. Of the latter, a noteworthy example is a prose translation of Oedipus Rex by Sophocles with annotations and explanatory notes that Martin describes as "surprisingly erudite".[3] The translation is accompanied by a twenty-page “… Essay on the Origin and Progress of Tragedy & on the Office & Advantages of the Antient Chorus"[3] where he provides a brief comparison of Sophocles and Euripides and argues in favour of the restoration of the Chorus in modern drama.[2]

His studies were interrupted when, in the summer of 1759, he and his father accompanied his mother to Highgate in England. Catherine's health had been deteriorating for some time and she now had increasing difficulty walking. After a short stay in Highgate she moved to the Roman Baths at Bath in Somerset, where the waters where supposed to have health-giving properties. Malone and his father returned to Ireland in October, too late to resume the winter term, so he elected to stay at Shinglas until the new year and study on his own. Not wishing to leave his father solitary, he nearly did not return to Trinity, but eventually resumed his studies in January 1760. The expenses for Catherine's stay at Bath put a strain on the family finances, but it was alleviated somewhat when, after a special examination on 2 June, he won a scholarship at Trinity and became a Scholar of the House.[5]

Malone's final examination at Trinity was in the Michaelmas term in 1761, and he received his BA degree at the following Commencement on 23 February 1762. As only one of three, he achieved the top mark (valde bene). The decision to study law was an obvious choice: his father, uncle, and grandfather had all been Irish Barristers. He'd received—on payment of £3 6s 8d—admittance to the Inner Temple in London in 1761, but did not begin his law studies until the new year in 1763. The interval was spent in Dublin reading, and he quickly applied to become a Reader of the Trinity College Library. Martin speculates that he spent his time reading "possibly law although probably also literature".[6][7]

Law school and legal practice

Malone probably entered the Inner Temple in January 1763, but few records survive of his studies there; except that he was "invited to come to the bench table"[8] in the commons—an honour Peter Martin describes as comparable to becoming a Warden in a guild[8]—on 10 May 1763. Outside schoolwork he published satirical articles about the government and on the abuse of the English language, and made corrections to the text in his copy of a new edition of Jonathan Swift's correspondence. He was admitted to the Inner Temple the same year as James Boswell—a coincidence Martin thinks "literary historians cannot fail to wonder at"[9]—but there is nothing to indicate that they ever crossed paths there.[8]

More significantly, in 1764, Malone's close friend Thomas Southwell and his father Edmund introduced Malone to Samuel Johnson, whose quarters on Inner Temple Lane were close to his own lodgings.[8] Martin describes it as “…the most important meeting of Malone's life"[8] and he became an "…ardent follower of Johnson's and, Boswell excepted, the most enthusiastic defender and celebrator of Johnson's writings and life."[8] Malone's friendship with Johnson lasted until the latter's death in 1784.[10] Although Malone failed to write down his conversations with Johnson, and none of his letters on the subject to John Chetwood have been found, Martin speculates that Shakespeare must have been among their topics of conversation, as Johnson was just then finishing up his great edition of Shakespeare that he had begun in 1756.[6] They would have found other common interests in the law and Ireland, as Johnson would soon start work as private secretary to the English statesman and Irish politician William Gerard Hamilton. For Hamilton he compiled notes on the Corn Laws that Malone in 1809 would publish, along with two of Hamilton's speeches in the Irish House of Commons and some other miscellaneous works, under the title Parliamentary Logick.[11]

The Southwells were also his companions when, in the autumn of 1766, he travelled in the south of France. There he visited Paris, Avignon, and Marseille; socialising and relaxing. Around this time he began having doubts about his choice of the law as a career. He was finished at the Inner Temple, but still required further study for the Irish Bar, and his motivation was flagging; particularly since it would mean leaving London and its "coffee-shops, theaters, newspapers, and politics."[12] There was also some tension between him and his father over this, and over a judgeship his father had been promised by Lord Worthington. On hearing that the judgeship might not come to pass, Malone wrote to his father: "It shall be a lesson to me, never to believe in any great man's word, unless coupled with performance, & to aspire by every truest means at the greatest blessing of life, independence."[13] Both issues resolved themselves shortly however, as his father succeeded to the bench as Judge of the Irish Court of Common Pleas while Malone was still in Marseille. Arriving back in London, without the Southwells, in February he announced his fresh determination to proceed with law: "It is my firm resolution to apply as closely as possible till I go to Ireland, to the study of law, & the practice of the Court of Chancery…"[12]

| “ | From the Person, parts & address of the young Lord, I thought the poor Girl payd dear enough for his Estate & title … I hope no child of mine will ever stoop to be exalted on such terms; domestic enjoyment in comfort & mediocrity has a thousand superior charms. | ” |

| — Edmond Malone, letter to Thomas Southwell[12] | ||

He was called to the Irish bar in 1767, and from 1769 practised law on the Munster circuit with "indifferent rewards".[10] He was not having great success in this field, and he missed London with its "…great literary world of Johnson, coffee-houses, theatre, newspapers, and politics."[12] In the early months of 1769 he also had an intense, but ultimately fruitless, romance with Susanna Spencer. When the relationship failed—for reasons that are unknown but which Martin speculates were related to their families' relative social status—Malone suffered a "nervous collapse"[12] and "[lost] the will to read, to join in family activities, to practice law."[12] He spent the better part of the summer in Spa with his brother, while his sisters, by letter, suggested remedies for his low mood and attempted to cheer him up. He returned some time after September, but his depression lingered on. He worked the Munster circuit and at some point after March in 1772 visited London, perhaps on the suggestion of his exasperated father. How long he remained or what his activities were is not known. He returned to Ireland and the Munster circuit, but, in private letters, complained of his boredom with this occupation.[14]

Literature, theatre, and politics

To relieve his boredom, Malone diverted himself with literary studies. On a visit with Dr. Thomas Wilson, Senior Fellow of Trinity College, in 1774 he discovered several papers by Alexander Pope that Henry St John, the poet's literary executor, had collected. Among them was a manuscript in Pope's handwriting of his unfinished poem One Thousand Seven Hundred and Forty. Malone transcribed a facsimile of the manuscript, including "interlineations, corrections, alterations",[15] but he failed to publish it and the original manuscript has since been lost.[14]

On 4 April 1774, the Irish-born author Oliver Goldsmith died. Malone had known Goldsmith, either in Dublin or in London in the 1760s, and to honour his friend he participated in an amateur production of Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer (1773). The event was held on 27 September 1774 and had strong patriotic overtones: it was staged at the country seat of Sir Hercules Langrishe—a member of the Irish House of Commons—at Knocktopher, and the Irish politicians and patriots Henry Grattan and Henry Flood both played parts. According to Martin's description, "Malone played two parts and wrote an excessively long epilogue of eighty-two lines, with several allusions that suggest his literary tastes. […] It celebrates Shakespeare, touches on Irish politics […], and concludes with a panegyric on the stage […]".[14]

Irish politics seems to have been especially on his mind in this period. In 1772 he contributed to Baratariana, a volume principally by Langrishe, but supplemented with letters by Flood and Grattan. The letters attack the current government in the style of Junius, who had published similar letters in England between 1769 and 1772, and Malone may have contributed "a weakly ironic piece in which he lamented the Irish consumption of millions of eggs every year when a little restraint could yield more substantial food in the form of chickens."[15] His father died unexpectedly on 22 March 1774, leaving the four siblings with a modest income, and Malone free to pursue interests outside the drudgery of his legal practice. His ambition was politics, and that summer he proposed himself as candidate to a seat in Parliament for Trinity College. Objections were raised that his uncle, Anthony Malone, had joined the Townshend government whose autocratic policies the university was firmly against. In his speech to the electors, Malone defended his uncle as a man of principle rather than party, who sought to do his best for his constituents rather than gain advantage for himself and his friends: "no man perhaps ever supported the administration so disinterestedly, or got so few favours from Government either for himself or his connexions."[16] To the charge that the filial association was an impediment to his nomination he protested, later in his speech:[16]

… I will go to the bottom of this objection, and will take it for granted that those who have thrown it out mean to insinuate that I was a dependant on another, and therefore not a proper object of your choice. And if this were the case, I would readily allow the force of the objection, and yield up all pretentions to your favour. But, gentlemen, this is as false as the rest; for a few months ago I obtained, at too high a price indeed, an honourable independence; nor shall any motive upon earth induce me to forfeit that independence.[lower-alpha 1]

Corruption and self-interest he saw as the great problem of men in elected office, and in his speech he attacked them as opposing reform for fear of losing their advantage:[16]

… a lord-lieutenant of the kingdom is besieged by men … who, in addition to great present emolument, grasp at future and numerous reversions; who, not content with the highest offices in their own line, invade the offices of other men, thrust themselves into every department, civil, military, and ecclesiastical …; who accumulate place upon place, and sinecure upon sinecure; who are so eager to obtain the wages of the day before the day is well passed over their heads, that they have emphatically and not improperly been styled ready-money voters; … men who are resolved … to aggrandize themselves, and care not how soon they subvert the constitution of their country if they can but erect the fabric of their own fortunes on its ruins.[lower-alpha 1]

He won the nomination, but the election was not until May 1776, and, a few days prior, Anthony Malone died, leaving Malone an annual income of £1,000 (roughly equivalent to £121,460 today)[lower-alpha 2] and the entire estate at Baronston to his brother, Richard.[18] The legacy left him free to pursue a life of scholarship, and he promptly gave up the nomination in favour of contributing to a new edition of Goldsmith that was being prepared. He travelled to London to interview the people who had known Goldsmith and collect information and anecdotes about him. He spent six months there but apart from a letter from Susanna Spencer, in reply to a letter from Malone that is now lost, we have no information about his activities there. In February 1777, suffering from his first bout of rheumatism, he returned to Ireland, and shortly afterward, Poems and Plays by Oliver Goldsmith was published. Malone had contributed an eight-page memoir of Goldsmith and annotations to the poems and plays. The memoir was based on "Authentic Anecdotes" by Richard Glover—published in The Universal Magazine in May 1774, and Edmund Burke included it in The Annual Register for that year—as well as first-hand information from Dr. Wilson at Trinity.[18]

London and Shakespeare

While in London to do research for his memoir of Goldsmith in 1776, Malone sought out George Steevens, who, by then the inheritor, from Samuel Johnson, of the editor's mantle for the Jacob Tonson edition of Shakespeare's collected works, was then busy preparing a second edition. Steevens invited Malone to help him complete it. To help him get started, Steevens lent Malone his copy of An Account of the English Dramatic Poets (1691) by Gerard Langbaine, into which Steevens had transcribed notes by William Oldys in addition to the notes he had added himself. When Malone returned to Ireland in early 1777, he set about transcribing all the annotations into his own copy.[lower-alpha 3] He finished the transcription on 30 March, and on 1 May he left Ireland for good.[19]

Malone moved into a house in Sunninghill, about 42 kilometres (26 mi) outside London, and started work.[20] In the following months he sent a steady stream of notes and corrections to Steevens and in January 1778 The Plays of William Shakspeare was published in 10 volumes. Malone's main contribution appeared in the first volume as "An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in Which the Plays Attributed to Shakspeare Were Written".[21] The "Attempt" was well received and garnered him more attention than the notes and corrections he had supplied Steevens with. With his first major contribution to Shakespeare studies published, he left Sunninghill to reside in London; first, briefly, in Marylebone Street and then in a house he rented at 55 Queen Anne Street East in what is now Foley Street in Marylebone.[22]

In late 1778 he visited Ireland for a few months, and in February 1779, shortly after he returned, he began to have his portrait painted by Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds was then much sought after as a portrait painter, and a "face and shoulders"[22] by Reynolds cost 35 guineas (£36.75). His uncle, Anothony Malone, had had his portrait painted by Reynolds in 1774, and Malone himself had good company: during the ten times between 23 February and 10 July that he sat for the portrait, Reynolds's appointment book shows that he sat on the same date as Edward Gibbon, the British historian and MP; George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough; Hester Thrale, author of Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson and a close friend of Johnson; and (28 April and 17 May) George III, then king of England and Ireland. Malone befriended Reynolds and they remained close friends until the latter's death in 1792, when Reynolds named Malone his executor along with Edmund Burke and Philip Metcalfe.[23]

Malone's next scholarly project was an addendum to the Johnson–Steevens Shakespeare. Pleased with Malone's contributions to the edition, Steevens invited him to publish the apocryphal plays that had been included in the second edition of the Third Folio published by Philip Chetwinde in 1664. It was Malone's project—and with only grudging acceptance from Steevens he expanded the work to include the narrative poems and the Sonnets—but he and Steevens worked closely together, and solicited notes from Isaac Reed, William Blackstone, and Thomas Percy.[24] Until this point their relationship had been a cordial and productive one—Steevens having given Malone his first opportunity as an editor of Shakespeare, and in return having benefitted greatly from the younger scholar's work—but while working on the addendum they had a falling out. Steevens brought up Susanna Spencer and suggested that Malone's work on Shakespeare was a mere device to keep his mind distracted from the unhappy relationship. Malone took umbrage at this, his ambition being a life of professional scholarship, and replied that, to the contrary, he intended to produce a completely new edition of Shakespeare, "more scientifically and methodically edited than the Johnson–Steevens edition was ever likely to become."[25] They settled their differences, but Steevens was now beginning to feel his position as the foremost editor of Shakespeare threatened. Malone was aggressive and arrogant, and his constant stream of corrections grated on the older editor.[26] Despite the strained relationship, in late April 1780, A Supplement to the Edition of Shakespeare, Published in 1778 by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens was published in two volumes. The work met with generally positive reviews, particularly from The Gentleman's Magazine and Monthly Review. But there was also criticism from the St. James's Chronicle, in which Steevens had a financial interest, that Martin describes as consisting of "anonymous and trifling notes […] which niggled at minor points, textual and factual",[27] which were probably written by Steevens or at his behest.[28]

Social rise and "The Club"

When Malone first arrived in England in 1777 he already had a connection to Samuel Johnson and George Steevens, and, through his boyhood friend Robert Jephson, to James Caulfeild, 1st Earl of Charlemont. Johnson, of course, was among the most esteemed men of letters, and Steevens was then the foremost commentator on Shakespeare and the current inheritor of the editor's mantle for the Tonson editions; but Charlemont also had the connections to introduce Malone to a wide variety of the eminent men of the day. With these recommendations and the fame garnered by his scholarly work he was by the early 1780s often to be found in the company of the greatest literary and theatrical minds of the era. He dined regularly with Johnson, Steevens, Reed, Reynolds, Richard Farmer, Horace Walpole, John Nichols, and John Henderson. But by this time Johnson's advancing age and ill health prevented his socialising as much as in earlier years, and Malone did not often enough get a chance to spend time with him or people like Edmund Burke, James Boswell, Edward Gibbon, Charles Burney, Joseph Banks, William Windham, Charles James Fox, or John Wilkes.[29]

At the same time, membership in "The Club"—founded by Johnson and Reynolds in 1764, and whose membership included several of those people whom Malone longed to see—had become a much sought-after honour. Malone dearly wanted to get in, but even though he had the support of Charlemont and Reynolds, he was thwarted by circumstances. The Club was founded specifically to be exclusive, and to that end limited the number of members, at that time to 35 at any given time. Since members very rarely left, the only openings came when a member died; and after the latest member, David Garrick, had died in 1779, the members resolved to keep his spot open in honour of the great actor and theatre manager. Votes were taken on several occasions, but the candidates were always blackballed.[30]

It was not until 5 February 1782 that "[…] the memory of Garrick having dimmed sufficiently, Malone at last was admitted into this august company […]".[31] He attended his first meeting on 19 February 1782 and quickly became one of The Club's most enthusiastic supporters and, as its treasurer, held the only permanent office associated with it. His motivation for wanting to join The Club was partly to see Johnson more often, but Johnson's health was deteriorating and no longer attended the club's dinners regularly. The first one he attended after Malone was accepted was on 2 April 1782, and in the period until Johnson's death on 13 December 1784, they saw each other at the club only five times; the last time on 22 June 1784, when Johnson "was in obvious pain and had to drag himself to get there."[32][lower-alpha 4] Johnson was also too ill to visit Malone, but he appreciated company at his house at Bolt Court, and Malone visited frequently. He kept notes on their conversations that Boswell later included in his The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791), and the letter to Malone from John Byng, 5th Viscount Torrington is the best account that survives of Johnson's last hours.[34]

Chatterton forgeries

_(14804959613).jpg)

In 1769, the poet Thomas Chatterton, only 17 years old, sent Horace Walpole the first of a series of poems supposedly written by a 15th-century monk named Thomas Rowley but really written by Chatterton himself. Other poems followed, and Walpole was briefly taken in but later reconsidered. When Chatterton committed suicide the following year, there were rumours that Walpole's treatment of the young man had played a part. Despite Walpole's scepticism, in 1777, shortly after Edmond Malone's arrival in London, Thomas Tyrwhitt published Chatterton's forgeries as Poems, Supposed to Have Been Written at Bristol, by Thomas Rowley and Others, in the Fifteenth Century. This created a great controversy, with much debate about their authenticity. For the third edition in 1778 he added an appendix arguing against the poems' antiquity, and Thomas Warton, in his The History of English Poetry (1778), devoted an entire chapter to it. Those favouring the authenticity of the Rowley poems responded in late 1781 when, just days apart, Jacob Bryant, a classical scholar, published Observations upon the Poems of Thomas Rowley; in Which the Authenticity of Those Poems is Ascertained, and Jeremiah Milles, Dean of Exeter and President of the Society of Antiquaries of London, published Poems, Supposed to Have Been Written at Bristol, in the Fifteenth Century, by Thomas Rowley, Priest, &c.; With a Commentary in Which the Antiquity of Them Is Considered and Defended.[35]

The controversy was a perfect match for Malone: steeped in ancient and early modern English literature, by trade a lawyer, and with no patience for literary forgeries or those who entertained them. As Martin puts it he "entered the fray"[36] in December 1781 by "[sending] an anonymous 'brat into the world'"[36] The "brat" was an article in two parts in The Gentleman's Magazine, signed "Misopiclerus". The essay met with success, and by February he published a second edition as Cursory Observations on the Poems Attributed to Thomas Rowley. In the essay he compares the Rowley poems to poetry by actual writers of the era;[lower-alpha 5] shows Chatterton's sources to have been later writers like Shakespeare, Pope, and Dryden; picks holes in the arguments put forward by Chatterton's supporters; and ends on an awkward attempt to ridicule Bryant and Milles.[38]

I do humbly recommend, that … the friends of the reverend antiquarian … and the learned mythologist … may, as soon as possible, convey the said [gentlemen] to the room over the north porch of Redcliffe church, … that in order to wean these gentlemen by degrees from the delusion under which they labour, and to furnish them with some amusement, they may be supplied with proper instruments to measure the length, breadth, and depth, of the empty chests now in the said room, and thereby to ascertain how many thousand diminutive pieces of parchment, all eight inches and a half by four and a half, might have been contained in those chests; (according to my calculation, 1,464,578;—but I cannot pretend to be exact:).

Works

- 1778 – "An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in Which the Plays Attributed to Shakspeare Were Written", in The Plays of William Shakespeare in Ten Volumes, Samuel Johnson and George Steevens, eds. (1778), 2nd ed., vol I, pp. 269–346.

- 1780 – Supplement to Johnson and Steevens's edition of Shakespeare's Plays.

- 1782 – Cursory Observations on the Poems Attributed to Thomas Rowley

- 1787 – A Dissertation on the Three Parts of King Henry VI.

- 1790 – The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare.

- 1792 – A Letter to the Rev. Richard Farmer; Relative to the Edition of Shakspeare, published in MDCCXC, and some late criticisms on that work. (This is the date of the 2nd edition.)

- 1796 – An inquiry into the authenticity of certain miscellaneous papers and legal instruments published 24 Dec MDCCXCV and attributed to Shakspeare, Queen Elizabeth and Henry, Earl of Southampton.

- 1800 – The Critical and Miscellaneous Prose Works of John Dryden, Now First Collected: With Notes and Illustrations; an Account of the Life and Writings of the Author Grounded on Original and Authentick Documents. Four volumes.

- 1801 – The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Knight.

- 1809 – Parliamentary Logick, the writings of William Gerard Hamilton with notes on the Corn Laws by Samuel Johnson.[6]

- 1809 – An account of the incidents from which the title and part of the story of Shakspeare's Tempest were derived; and its true date ascertained.

- 1821 – Life of Shakespeare. In Works of Shakespeare (1821), Volume II.

The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare

The years from 1783 to 1790 were devoted to Malone's own edition of Shakespeare in multiple volumes, of which his essays on the history of the stage, his biography of Shakespeare, and his attack on the genuineness of the three parts of Henry VI, were especially valuable. His editorial work was lauded by Burke, criticised by Walpole and damned by Joseph Ritson. It certainly showed indefatigable research and proper respect for the text of the earlier editions.

The Ireland forgeries

Malone published a denial of the claim to antiquity of the Rowley poems produced by Thomas Chatterton, and in this (1782) as in his branding (1796) of the Ireland manuscripts as forgeries, he was among the first to guess and state the truth. His elaborate edition of John Dryden's works (1800), with a memoir, was another monument to his industry, accuracy and scholarly care. In 1801 the University of Dublin made him an LL.D.

Malone–Boswell Shakespeare

At the time of his death, Malone was at work on a new octavo edition of Shakespeare, and he left his material to James Boswell the younger; the result was the edition of 1821 generally known as the Third Variorum edition in twenty-one volumes. Lord Sunderlin (1738–1816), his elder brother and executor, presented the larger part of Malone's book collection, including dramatic varieties, to the Bodleian Library, which subsequently bought many of his manuscript notes and his literary correspondence. The British Museum also owns some of his letters and his annotated copy of Johnson's Dictionary.

A memoir of Malone by James Boswell is included in the prolegomena to the edition of 1821.

Reputation and legacy

The Malone Society, devoted to the study of sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century English drama, was named after him.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- 1 2 The "Speech to the Electors of Trinity College, Dublin" is reproduced in Prior 1860.[17]

- ↑ UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- ↑ Malone's copy of Langbaine is now MS Malone 129 in the Bodleian Library.[19]

- ↑ The dinners were on 2 April 1782, 2 December 1782, 27 April 1783, 25 April 1784, and 22 June 1784.[33]

- ↑ He quotes in turn, works by William Langland, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, Thomas Hoccleve, John Lydgate, Hugh Campeden, Thomas Chestre, John Hardyng, Thomas Norton, Julian Barnes, William of Naffyngton, Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, Henry Bradshaw, Stephen Hawes, and John Skelton.[37]

References

- ↑ Lear 2010.

- 1 2 3 Martin 2005, pp. 1–3.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 3–5.

- 1 2 3 Martin 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 5.

- 1 2 Schoenbaum 1991, p. 112.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 10.

- 1 2 3 Martin 2005, pp. 11–14.

- 1 2 Martin 2005, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Martin 2005, p. 15.

- ↑ Prior 1860, pp. 467–9.

- 1 2 Martin 2005, p. 16–18.

- 1 2 Martin 2005, p. 18–19.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 30.

- 1 2 Martin 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 35–6.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 36–7.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 42.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 42–4.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 51.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 44–5, 51.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 52.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 52–3.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 53.

- ↑ Martin 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 53, 59.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 52–6, 58–60.

- ↑ Martin 2005, pp. 74–5.

- 1 2 Martin 2005, p. 75.

- ↑ Malone 1782, pp. 5–10.

- ↑ Malone 1782.

- ↑ Malone 1782, pp. 58–9.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Malone, Edmond". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Malone, Edmond". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Malone, Edmund". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Malone, Edmund". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource- de Grazia, Margreta (1991). Shakespeare Verbatim: The Reproduction of Authenticity and the 1790 Apparatus. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811778-7.

- Lear, Sophia (7 July 2010). "The Hidden God". The New Republic. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Malone, Edmond (1782). Cursory Observations on the Poems Attributed to Thomas Rowley (2nd ed.). London: J. Nichols. OCLC 604161349.

- Martin, Peter (2005) [first published 1995]. Edmond Malone, Shakespearean Scholar: A Literary Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-61982-3.

- Prior, James (2010) [first published 1860]. Life of Edmond Malone, Editor of Shakespeare: With Selections from His Manuscript Anecdotes. London: Smith, Elder & Co. ISBN 1-144-93232-7.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1991). Shakespeare's Lives. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-818618-5.

.jpg)