Edible mushroom

Edible mushrooms are the fleshy and edible fruit bodies of several species of macrofungi (fungi which bear fruiting structures that are large enough to be seen with the naked eye). They can appear either below ground (hypogeous) or above ground (epigeous) where they may be picked by hand.[1] Edibility may be defined by criteria that include absence of poisonous effects on humans and desirable taste and aroma.[2][3]

Edible mushrooms are consumed for their nutritional value and they are occasionally consumed for their supposed medicinal value. Mushrooms consumed by those practicing folk medicine are known as medicinal mushrooms.[4] While psychedelic mushrooms are occasionally consumed for recreational or entheogenic purposes, they can produce strong psychological effects, and are therefore not commonly used as food.[5]

Edible mushrooms include many fungal species that are either harvested wild or cultivated. Easily cultivatable and common wild mushrooms are often available in markets, and those that are more difficult to obtain (such as the prized truffle and matsutake) may be collected on a smaller scale by private gatherers. Some preparations may render certain poisonous mushrooms fit for consumption.

Before assuming that any wild mushroom is edible, it should be identified. Accurate determination and proper identification of a species is the only safe way to ensure edibility, and the only safeguard against possible accident. Some mushrooms that are edible for most people can cause allergic reactions in some individuals, and old or improperly stored specimens can cause food poisoning. Great care should therefore be taken when eating any fungus for the first time, and only small quantities should be consumed in case of individual allergies. Deadly poisonous mushrooms that are frequently confused with edible mushrooms and responsible for many fatal poisonings include several species of the Amanita genus, in particular, Amanita phalloides, the death cap. It is therefore better to eat only a few, easily recognizable species, than to experiment indiscriminately. Moreover, even species of mushrooms that normally are edible, may be dangerous, as mushrooms growing in polluted locations can accumulate pollutants such as heavy metals.[6]

History of mushroom use

Mycophagy /maɪˈkɒfədʒi/, the act of consuming mushrooms, dates back to ancient times. Edible mushroom species have been found in association with 13,000-year-old archaeological sites in Chile, but the first reliable evidence of mushroom consumption dates to several hundred years BC in China. The Chinese value mushrooms for medicinal properties as well as for food. Ancient Romans and Greeks, particularly the upper classes, used mushrooms for culinary purposes.[5] Food tasters were employed by Roman emperors to ensure that mushrooms were safe to eat.[7]

Mushrooms are also easily preserved, and historically have provided additional nutrition over winter.

Many cultures around the world have either used or continue to use psilocybin mushrooms for spiritual purposes as well as medicinal mushrooms in folk medicine, although these are not considered "edible" mushrooms in the culinary sense.

Current culinary use

Commercially cultivated

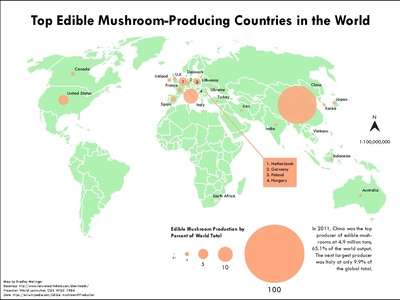

Mushroom cultivation has a long history, with over twenty species commercially cultivated. Mushrooms are cultivated in at least 60 countries[8] with China, the United States, Netherlands, France and Poland being the top five producers in 2000.

A fraction of the many fungi consumed by humans are currently cultivated and sold commercially. Commercial cultivation is important ecologically, as there have been concerns of depletion of larger fungi such as chanterelles in Europe, possibly because the group has grown popular, yet remains a challenge to cultivate.

Commercially harvested wild edibles

Some species are difficult to cultivate; others (particularly mycorrhizal species) have not yet been successfully cultivated. Some of these species are harvested from the wild, and can be found in markets. When in season they can be purchased fresh, and many species are sold dried as well. The following species are commonly harvested from the wild:

- Boletus edulis or edible Boletus, native to Europe, known in Italian as Fungo Porcino (plural 'porcini') (Pig mushroom), in German as Steinpilz (Stone mushroom), in Russian as "white mushroom", in Albanian as (Wolf mushroom), in French the cèpe and in the UK as the Penny Bun. It also known as the king bolete, and is renowned for its delicious flavor. It is sought after worldwide, and can be found in a variety of culinary dishes.

- Cantharellus cibarius (The chanterelle), The yellow chanterelle is one of the best and most easily recognizable mushrooms, and can be found in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. There are poisonous mushrooms which resemble it, though these can be confidently distinguished if one is familiar with the chanterelle's identifying features.

- Cantharellus tubaeformis, the tube chanterelle or yellow-leg

- Clitocybe nuda, Blewit (or Blewitt)

- Cortinarius caperatus, the Gypsy mushroom (recently moved from genus Rozites)

- Craterellus cornucopioides, Trompette de la Mort or Horn of Plenty

- Grifola frondosa, known in Japan as maitake (also "hen of the woods" or "sheep’s head"); a large, hearty mushroom commonly found on or near stumps and bases of oak trees, and believed to have Macrolepiota procera properties.

- Gyromitra esculenta, this "False morel" is prized by the Finns. This mushroom is deadly poisonous if eaten raw, but highly regarded when parboiled (see below).

- Hericium erinaceus, a tooth fungus; also called "lion's mane mushroom"

- Hydnum repandum, Sweet tooth fungus, Hedgehog mushroom or Hedgehog Fungus, urchin of the woods

- Lactarius deliciosus, Saffron milk cap, consumed around the world and prized in Russia

- Morchella species, (morel family) morels belong to the ascomycete grouping of fungi. They are usually found in open scrub, woodland or open ground in late spring. When collecting this fungus, care must be taken to distinguish it from the poisonous false morels, including Gyromitra esculenta. The Morel must be cooked before eating.

- Morchella conica var. deliciosa

- Morchella esculenta var. rotunda

- Pleurotus ostreatus, (Oyster Mushroom)

- Tricholoma matsutake, the Matsutake, a mushroom highly prized in Japanese cuisine.

- Tuber, species, (the truffle), Truffles have long eluded the modern techniques of domestication known as trufficulture. Although the field of trufficulture has greatly expanded since its inception in 1808, several species still remain uncultivated. Domesticated truffles include

- Tuber borchii

- Tuber brumale

- Tuber indicum, Chinese black truffle

- Tuber macrosporum, Smooth black truffle

- Tuber mesentericum, The Bagnoli truffle[9]

- Tuber aestivum, Black summer truffle

Chanterelles in the wild

Chanterelles in the wild A collection of Boletus edulis of varying ages

A collection of Boletus edulis of varying ages Hericium coralloides

Hericium coralloides Clitocybe nuda

Clitocybe nuda Black Périgord Truffle, cut

Black Périgord Truffle, cut

Other edible wild species

Many wild species are consumed around the world. The species which can be identified "in the field" (without use of special chemistry or a microscope) and therefore safely eaten vary widely from country to country, even from region to region. This list is a sampling of lesser-known species that reported as edible.

- Amanita caesarea (Caesar's Mushroom)

- Armillaria mellea

- Agaricus arvensis (Horse Mushroom)

- Agaricus silvaticus (Pinewood Mushroom)

- Boletus badius (Bay Bolete)

- Chroogomphus rutilus (pine-spikes or spike-caps)

- Calvatia gigantea (Giant Puffball)

- Calvatia utriformis (Lycoperdon caelatum)

- Calocybe gambosa (St George's mushroom)

- Clavariaceae species (coral fungus family)

- Clavulinaceae species (coral fungus family)

- Coprinus comatus, the Shaggy mane, Shaggy Inkcap or Lawyer's Wig. Must be cooked as soon as possible after harvesting or the caps will first turn dark and unappetizing, then deliquesce and turn to ink. Not found in markets for this reason.

- Corn smut

- Cyttaria espinosae

- Cortinarius variicolor

- Fistulina hepatica (beefsteak polypore or the ox tongue)

- Flammulina velutipes (Velvet Shank or Winter Fungus)

- Hygrophorus chrysodon

.jpg)

- Lactarius deterrimus (Orange Milkcap)

- Lactarius salmonicolor

- Lactarius subdulcis (mild milkcap)

- Lactarius volemus

- Laetiporus sulphureus (Sulphur shelf). Also known by names such as the "chicken mushroom", "chicken fungus", sulphur shelf is a distinct bracket fungus popular among mushroom hunters.

- Leccinum aurantiacum (Red-capped scaber stalk)

- Leccinum scabrum (Birch bolete)

- Leccinum versipelle (Orange Birch Bolete / Boletus testaceoscaber)

- Macrolepiota procera (Parasol Mushroom). Globally, it is widespread in temperate regions

- Marasmius oreades (Fairy Ring Champignon)

- Polyporus squamosus (Dryad's saddle and Pheasant's back mushroom)

- Polyporus mylittae

- Ramariaceae species (coral fungus family)

- Rhizopogon luteolus

- Russula, some members of this genus, such as R. laeta, are edible.

- Sparassis crispa. Also known as "cauliflower mushroom"

- Suillus bovinus

- Suillus granulatus

- Suillus luteus

- Suillus tomentosus

- Tricholoma terreum

Conditionally-edible species

There are a number of fungi that are considered choice by some and toxic by others. In some cases, proper preparation can remove some or all of the toxins.

- Amanita fulva (Tawny Grisette) must be cooked before eating.

- Amanita muscaria is edible if parboiled to leach out toxins,[10] fresh mushrooms cause vomiting, twitching, drowsiness, and hallucinations due to the presence of muscimol. Although present in A. muscaria, ibotenic acid is not in high enough concentration to produce any physical or psychological effects unless massive amounts are ingested.

- Amanita rubescens (The Blusher) must be cooked before eating.

- Coprinopsis atramentaria is edible without special preparation, however, consumption with alcohol is toxic due to the presence of coprine. Some other Coprinus spp. share this property.

- Gyromitra esculenta is eaten by some after it has been parboiled, however, mycologists do not recommend it. Raw Gyromitra are toxic due to the presence of gyromitrin, and it is not known whether all of the toxin can be removed by parboiling.

- Lactarius spp. Apart from Lactarius deliciosus, which is universally considered edible, other Lactarius spp. that are considered toxic elsewhere in the world are eaten in some Eastern European countries and Russia after pickling or parboiling.[11]

- Lepista nuda (Wood Blewit) must be cooked before eating.

- Lepista saeva (Field Blewit, Blue Leg, or Tricholoma personatum) must be cooked before eating.

- Morchella esculenta (Morel) must be cooked before eating.

- Verpa bohemica is considered choice by some—it even can be found for sale as a "morel"—but cases of toxicity have been reported. Verpas contain toxins similar to gyromitrin[12] and similar precautions apply.

Nutrients

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 93 kJ (22 kcal) |

|

3.3 g | |

|

0.3 g | |

|

3.1 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(7%) 0.08 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(33%) 0.4 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(24%) 3.6 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(30%) 1.5 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(8%) 0.1 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(4%) 17 μg |

| Vitamin B12 |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Choline |

(4%) 17.3 mg |

| Vitamin D |

(1%) 7 IU |

| Vitamin E |

(0%) 0 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(0%) 3 mg |

| Copper |

(16%) 0.32 mg |

| Iron |

(4%) 0.5 mg |

| Magnesium |

(3%) 9 mg |

| Manganese |

(2%) 0.05 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(12%) 86 mg |

| Potassium |

(7%) 318 mg |

| Selenium |

(13%) 9.3 μg |

| Zinc |

(5%) 0.52 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 92 g |

|

| |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 117 kJ (28 kcal) |

|

5.3 g | |

|

0.5 g | |

|

2.2 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(9%) 0.1 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(25%) 0.3 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(30%) 4.5 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(44%) 2.2 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(8%) 0.1 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(5%) 18 μg |

| Vitamin B12 |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Choline |

(4%) 19.9 mg |

| Vitamin D |

(4%) 21 IU |

| Vitamin E |

(0%) 0 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(0%) 0 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(1%) 6 mg |

| Copper |

(25%) 0.5 mg |

| Iron |

(13%) 1.7 mg |

| Magnesium |

(3%) 12 mg |

| Manganese |

(5%) 0.1 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(12%) 87 mg |

| Potassium |

(8%) 356 mg |

| Selenium |

(19%) 13.4 μg |

| Zinc |

(9%) 0.9 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 91.1 g |

|

| |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

A commonly eaten mushroom is the white mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). In 100 grams, these provide 22 calories and are composed of 92% water, 3% carbohydrates, 3% protein and 0.3% fat (table). They contain high levels (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of riboflavin, niacin, and pantothenic acid (24–33% DV), with lower moderate content of phosphorus (table). Otherwise, raw white mushrooms generally have low amounts of essential nutrients (table).

Although cooking (by boiling) lowers mushroom water content only 1%, the contents per 100 grams for several nutrients increase appreciably, especially for dietary minerals (table for boiled mushrooms).

The content of vitamin D is absent or low unless mushrooms are exposed to sunlight or purposely treated with artificial ultraviolet light (see below).

Vitamin D

Mushrooms exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light produce vitamin D2 before or after harvest by converting ergosterol, a chemical found in large concentrations in mushrooms, to vitamin D2.[13][14][15] This is similar to the reaction in humans, where vitamin D3 is synthesized after exposure to sunlight.

Testing showed an hour of UV light exposure before harvesting made a serving of mushrooms contain twice the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's daily recommendation of vitamin D, and 5 minutes of UV light exposure after harvesting made a serving of mushrooms contain four times the FDA's daily recommendation of vitamin D.[13] Analysis also demonstrated that natural sunlight produced vitamin D2.[14]

The ergocalciferol, vitamin D2, in UV-irradiated mushrooms is not the same form of vitamin D as is produced by UV-irradiation of human skin or animal skin, fur, or feathers (cholecalciferol, vitamin D3). Although vitamin D2 clearly has vitamin D activity in humans and is widely used in food fortification and in nutritional supplements, vitamin D3 is often used in dairy and cereal products.

| Name | Chemical composition | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D1 | ergocalciferol with lumisterol, 1:1[16] | |

| Vitamin D2 | ergocalciferol (made from ergosterol) |  |

| Vitamin D3 | cholecalciferol (made from 7-Dehydrocholesterol in the skin). |  |

Use in traditional medicine

Medicinal mushrooms are mushrooms or extracts from mushrooms that are thought to be treatments for diseases, yet remain unconfirmed in mainstream science and medicine, and so are not approved as drugs or medical treatments.[17] Such use of mushrooms therefore falls into the domain of traditional medicine.

Preliminary research on mushroom extracts has been conducted to determine if anti-disease properties exist, such as for polysaccharide-K,[18] polysaccharide peptide,[19] or lentinan.[20] Some extracts have widespread use in Japan, Korea and China, as potential adjuvants to radiation treatments and chemotherapy.[21][22]

The concept of a medicinal mushroom has a history spanning millennia in parts of Asia, mainly as traditional Chinese medicine.[23]

Reishi, a well-known mushroom

Reishi, a well-known mushroom- Chicken of the woods, a mushroom used as a substitute for chicken meat

- Common Morel

Preparing edible mushrooms

Some wild species are toxic, or at least indigestible, when raw.[24] As a rule all mushroom species should be cooked thoroughly before eating. Many species can be dried and rehydrated by pouring boiling water over the dried mushrooms and letting them steep for approximately 30 minutes. The soaking liquid can be used for cooking as well, provided that any dirt at the bottom of the container is discarded.

Cell walls of mushrooms contain chitin, which is not easily digestible by humans. Cooking will help break down the chitin making cell contents. High speed blending can have a similar effect, but will not degrade mild toxins and carcinogens which are present in some edible species.

Failure to identify poisonous mushrooms and confusing them with edible ones has resulted in death.[24][25][26]

A collection of dried mushrooms

A collection of dried mushrooms Stuffed mushrooms prepared using portabello mushrooms

Stuffed mushrooms prepared using portabello mushrooms

Production

| Country | Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tonnes | long tons | short tons | % of world output | |

| Albania | 123 | 121 | 136 | 0.00160 |

| Algeria | 220 | 220 | 240 | 0.00286 |

| Australia | 49,696 | 48,911 | 54,780 | 0.646 |

| Austria | 1,600 | 1,600 | 1,800 | 0.0208 |

| Azerbaijan | 1,450 | 1,430 | 1,600 | 0.0188 |

| Belarus | 5,934 | 5,840 | 6,541 | 0.0771 |

| Belgium | 41,556 | 40,900 | 45,808 | 0.540 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 994 | 978 | 1,096 | 0.0129 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 11 | 11 | 12 | 0.000143 |

| Bulgaria | 2,171 | 2,137 | 2,393 | 0.0282 |

| Canada | 78,930 | 77,680 | 87,010 | 1.03 |

| People's Republic of China | 5,008,850 | 4,929,740 | 5,521,310 | 65.1 |

| Cyprus | 730 | 720 | 800 | 0.00948 |

| Czech Republic | 361 | 355 | 398 | 0.00469 |

| Denmark | 10,304 | 10,141 | 11,358 | 0.134 |

| Estonia | 125 | 123 | 138 | 0.00162 |

| Finland | 1,668 | 1,642 | 1,839 | 0.0217 |

| France | 115,669 | 113,842 | 127,503 | 1.50 |

| Germany | 62,000 | 61,000 | 68,000 | 0.805 |

| Greece | 3,255 | 3,204 | 3,588 | 0.0423 |

| Hungary | 14,249 | 14,024 | 15,707 | 0.185 |

| Iceland | 583 | 574 | 643 | 0.00757 |

| India | 41,000 | 40,000 | 45,000 | 0.533 |

| Indonesia | 45,851 | 45,127 | 50,542 | 0.596 |

| Iran | 37,664 | 37,069 | 41,517 | 0.489 |

| Ireland | 67,063 | 66,004 | 73,924 | 0.871 |

| Israel | 10,001 | 9,843 | 11,024 | 0.130 |

| Italy | 761,858 | 749,826 | 839,805 | 9.90 |

| Japan | 60,180 | 59,230 | 66,340 | 0.782 |

| Jordan | 1,123 | 1,105 | 1,238 | 0.0146 |

| Kazakhstan | 558 | 549 | 615 | 0.00725 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 201 | 198 | 222 | 0.00261 |

| Latvia | 517 | 509 | 570 | 0.00672 |

| Lithuania | 13,008 | 12,803 | 14,339 | 0.169 |

| Luxembourg | 5 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 0.0000649 |

| Madagascar | 2,087 | 2,054 | 2,301 | 0.0271 |

| Malta | 947 | 932 | 1,044 | 0.0123 |

| Moldova | 475 | 467 | 524 | 0.00617 |

| Mongolia | 278 | 274 | 306 | 0.00361 |

| Morocco | 2,045 | 2,013 | 2,254 | 0.0266 |

| Netherlands | 304,000 | 299,000 | 335,000 | 3.95 |

| New Zealand | 9,884 | 9,728 | 10,895 | 0.128 |

| North Korea | 6,777 | 6,670 | 7,470 | 0.0880 |

| Philippines | 571 | 562 | 629 | 0.00742 |

| Poland | 198,235 | 195,104 | 218,517 | 2.57 |

| Portugal | 1,240 | 1,220 | 1,370 | 0.0161 |

| Romania | 7,661 | 7,540 | 8,445 | 0.0995 |

| Russia | 4,200 | 4,100 | 4,600 | 0.0546 |

| Réunion | 61 | 60 | 67 | 0.000792 |

| Serbia | 4,851 | 4,774 | 5,347 | 0.0630 |

| Singapore | 200 | 200 | 220 | 0.00260 |

| Slovakia | 1,898 | 1,868 | 2,092 | 0.0247 |

| Slovenia | 1,060 | 1,040 | 1,170 | 0.0138 |

| South Africa | 12,568 | 12,370 | 13,854 | 0.163 |

| South Korea | 30,574 | 30,091 | 33,702 | 0.397 |

| Spain | 127,000 | 125,000 | 140,000 | 1.65 |

| Switzerland | 8,465 | 8,331 | 9,331 | 0.110 |

| Thailand | 6,791 | 6,684 | 7,486 | 0.0882 |

| Macedonia | 2,784 | 2,740 | 3,069 | 0.0362 |

| Tunisia | 122 | 120 | 134 | 0.00158 |

| Turkey | 27,058 | 26,631 | 29,826 | 0.351 |

| Ukraine | 14,000 | 14,000 | 15,000 | 0.182 |

| United Kingdom | 69,300 | 68,200 | 76,400 | 0.900 |

| United States | 390,902 | 384,728 | 430,896 | 5.08 |

| Uzbekistan | 661 | 651 | 729 | 0.00859 |

| Vietnam | 21,957 | 21,610 | 24,203 | 0.285 |

| Zimbabwe | 613 | 603 | 676 | 0.00796 |

| World | 7,698,773 | 7,577,183 | 8,486,445 | 100 |

See also

References

- ↑ Chang, Shu-Ting; Phillip G. Miles (1989). Mushrooms: cultivation, nutritional value, medicinal effect, and Environmental Impact. CRC Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 0-8493-1043-1.

- ↑ Arora D (1986). Mushrooms demystified. Ten Speed Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ↑ Mattila P, Suonpää K, Piironen V (2000). "Functional properties of edible mushrooms". Nutrition. 16 (7–8): 694–6. PMID 10906601. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00341-5.

- ↑ Ejelonu, O.C; Akinmoladun, A.C; Elekofehinti, O.O; Olaleye, M.T. "antioxidant profile of four selected wild edible mushrooms in Nigeria". journal of chemical and pharmaceutical research. 7: 286–295.

- 1 2 Boa E. (2004). Wild Edible Fungi: A Global Overview of their Use and Importance to People. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-105157-7.

- ↑ Kalač, Pavel; Svoboda, Lubomı́r (15 May 2000). "A review of trace element concentrations in edible mushrooms". Food Chemistry. 69 (3): 273–281. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00264-2.

- ↑ Jordan P. (2006). Field Guide to Edible Mushrooms of Britain and Europe. New Holland Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84537-419-8.

- ↑ John Fereira. "U.S. Mushroom Industry". Usda.mannlib.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ T. mesenterium was first reported in Great Britain after the wet August 2008: "New fungi species unearthed in UK". BBC News. 9 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ↑ Rubel W, Arora D (2008). "A study of cultural bias in field guide determinations of mushroom edibility using the iconic mushroom, Amanita muscaria, as an example" (PDF). Economic Botany. 62 (3): 223–43. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9040-9.

- ↑ Arora, David. Mushrooms Demystified, 2nd ed. Ten Speed Press, 1986

- ↑ FDA IMPORT ALERT IA2502 Archived April 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Bowerman S (March 31, 2008). "If mushrooms see the light". Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 Koyyalamudi SR, Jeong SC, Song CH, Cho KY, Pang G (April 2009). "Vitamin D2 formation and bioavailability from Agaricus bisporus button mushrooms treated with ultraviolet irradiation". J Agric Food Chem. 57 (8): 3351–5. PMID 19281276. doi:10.1021/jf803908q.

- ↑ Lee GS, Byun HS, Yoon KH, Lee JS, Choi KC, Jeung EB (March 2009). "Dietary calcium and vitamin D2 supplementation with enhanced Lentinula edodes improves osteoporosis-like symptoms and induces duodenal and renal active calcium transport gene expression in mice". Eur J Nutr. 48 (2): 75–83. PMID 19093162. doi:10.1007/s00394-008-0763-2.

- ↑ Kalaras MD, Beelman RB, Holick MF, Elias RJ (2012). "Generation of potentially bioactive ergosterol-derived products following pulsed ultraviolet light exposure of mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus).". Food Chem. 135 (2): 396–401. PMID 22868105. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.04.132.

- ↑ Sullivan R, Smith JE, Rowan NJ (2006). "Medicinal mushrooms and cancer therapy: translating a traditional practice into Western medicine". Perspect Biol Med. 49 (2): 159–70. PMID 16702701. doi:10.1353/pbm.2006.0034.

- ↑ "Coriolus Versicolor". About Herbs, Botanicals & Other Products. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

- ↑ Ng, T. B. (1998). "A review of research on the protein-bound polysaccharide (polysaccharopeptide, PSP) from the mushroom Coriolus versicolor (basidiomycetes: Polyporaceae)". General Pharmacology: the Vascular System. 30 (1): 1–4. PMID 9457474. doi:10.1016/S0306-3623(97)00076-1.

- ↑ "Lentinan (Shiitake)". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ Sullivan, Richard; Smith, John E.; Rowan, Neil J. (2006). "Medicinal Mushrooms and Cancer Therapy: translating a traditional practice into Western medicine". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 49 (2): 159–70. PMID 16702701. doi:10.1353/pbm.2006.0034.

- ↑ Borchers, A. T.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Keen, C. L.; Meyers, F. J.; Gershwin, M. E. (2008). "The Immunobiology of Mushrooms". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 233 (3): 259–76. PMID 18296732. doi:10.3181/0708-MR-227.

- ↑ Hobbs CJ. (1995). Medicinal Mushrooms: An Exploration of Tradition, Healing & Culture. Portland, Oregon: Culinary Arts Ltd. p. 20. ISBN 1-884360-01-7.

- 1 2 "Wild Mushroom Warning. Mushroom Poisoning: Don't Invite "The Death Angel" to Dinner". US National Capital Poison Center, Washington, DC. 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ Barbee G, Berry-Cabán C, Barry J, Borys D, Ward J, Salyer S (2009). "Analysis of mushroom exposures in Texas requiring hospitalization, 2005–2006". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (2): 59–62. PMC 3550325

. PMID 19415588. doi:10.1007/BF03161087.

. PMID 19415588. doi:10.1007/BF03161087. - ↑ Osborne, Tegan. "Deadly death cap mushrooms found in Canberra's inner-south as season begins early". ABC News. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edible mushrooms. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

-

"Mushrooms". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Mushrooms". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

.jpg)