Romanian Orthodox Church

| Romanian Orthodox Church (Patriarchate of Romania) | |

|---|---|

|

Coat of arms | |

| Founder |

(as Metropolis of Romania) Miron Cristea, Ferdinand I |

| Independence | 1872 |

| Recognition | 25 April 1885 |

| Primate | Daniel, Patriarch of All Romania |

| Headquarters | Dealul Mitropoliei, Bucharest |

| Territory |

|

| Possessions |

Western and Southern Europe; Germany, Central and Northern Europe; Americas; Australia and New Zealand |

| Language | Romanian |

| Members | 16,367,267 in Romania;[1] 720,000 in Moldova[2] 11,203 in United States[3] |

| Bishops | 53 [4] |

| Priests | 15,068 [4] |

| Parishes | 15,717 [4] |

| Monastics | 2,810 (men), 4,795 (women) [4] |

| Monasteries | 359 [4] |

| Website | http://www.patriarhia.ro/ |

The Romanian Orthodox Church (Romanian: Biserica Ortodoxă Română) is an autocephalous Orthodox Church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian Churches and ranked seventh in order of precedence. Since 1925, the Church's Primate bears the title of Patriarch. Its jurisdiction covers the territories of Romania and Moldova, with additional dioceses for Romanians living in nearby Serbia and Hungary, as well as for diaspora communities in Central and Western Europe, North America and Oceania.

Currently it is the only self-governing Church within Orthodoxy to have a Romance language for its principal and native tongue. The majority of Romania's population (16,307,004, or 86.5% of those for whom data were available, according to the 2011 census data[5]), as well as some 720,000 Moldovans,[2] belong to the Romanian Orthodox Church. The Romanian Orthodox Church is the second-largest in size behind the Russian Orthodox Church.

Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church sometimes refer to Orthodox Christian doctrine as Dreapta credință ("right/correct belief" or "true faith"; compare to Greek ὀρθὴ δόξα, "straight/correct belief").

History

.png)

.png)

In the Kingdom of Romania

In 1859, the political union of the Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia resulted in the formation of the modern state of Romania. Since the territorial organization of the Orthodox churches tends to follow that of the state, in 1872, the Orthodox churches of the former principalities, the Metropolis of Ungro-Wallachia and the Metropolis of Moldavia, merged to form the Romanian Orthodox Church.

The 1866 Constitution of Romania declared the Orthodox Church to be "independent of any foreign hierarchy", and a law passed in 1872 declared the church to be "autocephalous". After a long period of negotiations with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the latter finally recognized the Metropolis of Romania in 1885, which was eventually raised to the rank of Patriarchate in 1925.[6]

Communist period

Restricted access to ecclesiastical and relevant state archives[7][8] makes an accurate assessment of the Romanian Orthodox Church's attitude towards the Communist regime a difficult proposition. Nevertheless, the activity of the Orthodox Church as an institution was more or less tolerated by the Marxist–Leninist atheist regime, although it was controlled through "special delegates" and its access to the public sphere was severely limited; the regime's attempts at repression generally focused on individual believers.[9] The attitudes of the church's members, both laity and clergy, towards the communist regime, range broadly from opposition and martyrdom, to silent consent, collaboration or subservience aimed at ensuring survival. Beyond limited access to the Securitate and Party archives as well as the short time elapsed since these events unfolded, such an assessment is complicated by the particularities of each individual and situation, the understanding each had about how their own relationship with the regime could influence others and how it actually did.[10][11]

The Romanian Communist Party, which assumed political power at the end of 1947, initiated mass purges that resulted in a decimation of the Orthodox hierarchy. Three archbishops died suddenly after expressing opposition to government policies, and thirteen more "uncooperative" bishops and archbishops were arrested.[12] A May 1947 decree imposed a mandatory retirement age for clergy, thus providing authorities with a convenient way to pension off old-guard holdouts. The 4 August 1948 Law on Cults institutionalised state control over episcopal elections and packed the Holy Synod with Communist supporters.[13] The evangelical wing of the Romanian Orthodox Church, known as the Army of the Lord, was suppressed by communist authorities in 1948.[14] In exchange for subservience and enthusiastic support for state policies, the property rights over as many as 2,500 church buildings and other assets belonging to the (by then-outlawed) Romanian Greek-Catholic Church were transferred to the Romanian Orthodox Church; the government took charge of providing salaries for bishops and priests, as well as financial subsidies for the publication of religious books, calendars and theological journals.[15] By weeding out the anti-communists from among the Orthodox clergy and setting up a pro-regime, secret police-infiltrated Union of Democratic Priests (1945), the party endeavoured to secure the hierarchy's cooperation. By January 1953 some 300-500 Orthodox priests were being held in concentration camps, and following Patriarch Nicodim's death in May 1948, the party succeeded in having the ostensibly docile Justinian Marina elected to succeed him.[12]

As a result of measures passed in 1947-48, the state took over the 2,300 elementary schools and 24 high schools operated by the Orthodox Church. A new campaign struck the church in 1958-62 when more than half of its remaining monasteries were closed, more than 2,000 monks were forced to take secular jobs, and about 1,500 clergy and lay activists were arrested (out of a total of up to 6,000 in the 1946-64 period[15]). Throughout this period Patriarch Justinian took great care that his public statements met the regime's standards of political correctness and to avoid giving offence to the government;[16] indeed the hierarchy at the time claimed that the arrests of clergy members were not due to religious persecution.[13]

The church's situation began to improve in 1962, when relations with the state suddenly thawed, an event that coincided with the beginning of Romania's pursuit of an independent foreign policy course that saw the political elite encourage nationalism as a means to strengthen its position against Soviet pressure. The Romanian Orthodox Church, an intensely national body that had made significant contributions to Romanian culture from the 14th century on, came to be regarded by the regime as a natural partner. As a result of this second co-optation, this time as an ally, the church entered a period of dramatic recovery. By 1975, its diocesan clergy was numbering about 12,000, and the church was already publishing by then eight high-quality theological reviews, including Ortodoxia and Studii Teologice. Orthodox clergymen consistently supported the Ceaușescu regime's foreign policy, refrained from criticizing domestic policy, and upheld the Romanian government's line against the Soviets (over Bessarabia) and the Hungarians (over Transylvania). As of 1989, two metropolitan bishops even sat in the Great National Assembly.[16] The members of the church's hierarchy and clergy remained mostly silent as some two dozen historic Bucharest churches were demolished in the 1980s, and as plans for systematization (including the destruction of village churches) were announced.[17] A notable dissenter was Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa, imprisoned for a number of years and eventually expelled from Romania in June 1985, after signing an open letter criticizing and demanding an end to the regime's violations of human rights.[15]

In an attempt to adapt to the newly created circumstances, the Orthodox Church proposed a new ecclesiology designed to justify its subservience to the state in supposedly theological terms. This so-called "Social Apostolate" doctrine, developed by Patriarch Justinian, asserted that the church owed allegiance to the secular government and should put itself at its service. This notion inflamed conservatives, who were consequently purged by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu's predecessor and a friend of Justinian's. The Social Apostolate called on clerics to become active in the People's Republic, thus laying the foundation for the church's submission to and collaboration with the state. Fr. Vasilescu, an Orthodox priest, attempted to find grounds in support of the Social Apostolate doctrine in the Christian tradition, citing Augustine of Hippo, John Chrysostom, Maximus the Confessor, Origen and Tertullian. Based on this alleged grounding in tradition, Vasilescu concluded that Christians owed submission to their secular rulers as if it were the will of God. Once recalcitrants were removed from office, the remaining bishops adopted a servile attitude, endorsing Ceauşescu's concept of nation, supporting his policies, and applauding his peculiar ideas about peace.[18]

Collaboration with the Securitate

In the wake of the Romanian Revolution, the Church never admitted to having ever willingly collaborated with the regime, although several Romanian Orthodox priests have publicly admitted after 1989 that they had collaborated with and/or served as informers for the Securitate, the Romanian Communist secret police. A prime example was Bishop Nicolae Corneanu, the Metropolitan of Banat, who admitted to his efforts on behalf of the Communist Party, and denounced activities of clerics in support of the Communists, including his own, as "the Church's [act of] prostitution with the Communist regime".[13]

In 1986, Metropolitan Antonie Plămădeală defended Ceaușescu's church demolition program as part of the need for urbanization and modernization in Romania.[19]The church hierarchy refused to try to inform the international community about what was happening.[20]

Widespread dissent from religious groups in Romania did not appear until revolution was sweeping across Eastern Europe in 1989. The Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church Teoctist Arăpașu supported Ceaușescu up until the end of the regime, and even congratulated him after the state murdered one hundred demonstrators in Timișoara.[21] It was not until the day before Ceaușescu's execution on 24 December 1989 that the Patriarch condemned him as "a new child-murdering Herod".[22]

Following the removal of Communism, the Patriarch resigned (only to return a few months after) and the holy synod apologized for those 'who did not have the courage of the martyrs'.<[23]

After 1989

As Romania made the transition to democracy, the Church was freed from most of its state control, although the State Secretariat for Religious Denominations still maintains control over a number of aspects of the church's management of property, finances and administration. The state provides funding for the church in proportion to the number of its members, based on census returns[24] and "the religion's needs" which is considered to be an "ambiguous provision".[25] Currently, the state provides the funds necessary for paying the salaries of priests, deacons and other prelates and the pensions of retired clergy, as well as for expenses related to lay church personnel. For the Orthodox church this is over 100 million euros for salaries,[26] with additional millions for construction and renovation of church property. The same applies to all state-recognised religions in Romania.

The state also provides support for church construction and structural maintenance, with a preferential treatment of Orthodox parishes.[27] The state funds all the expenses of Orthodox seminaries and colleges, including teachers' and professors' salaries who, for compensation purposes, are regarded as civil servants.

Since the fall of Communism, Greek-Catholic Church leaders have claimed that the Eastern Catholic community is facing a cultural and religious wipe-out: the Greek-Catholic churches are allegedly being destroyed by representatives of the Orthodox Church, whose actions are supported and accepted by the Romanian authorities.[28]

In the Republic of Moldova

The Romanian Orthodox Church also has jurisdiction over a minority of believers in Moldova, who belong to the Metropolis of Bessarabia, as opposed to the majority, who belong to the Moldovan Orthodox Church, under the Moscow Patriarchate. In 2001 it won a landmark legal victory against the Government of Moldova at the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights.

This means that despite current political issues, the Metropolis of Bessarabia is now recognized as "the rightful successor" to the Metropolitan Church of Bessarabia and Hotin, which existed from 1927 until its dissolution in 1944, when its canonical territory was put under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church's Moscow Patriarchate in 1947.

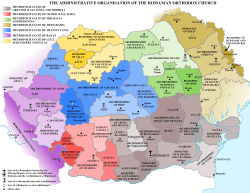

Organization

The Romanian Orthodox Church is organized in the form of the Romanian Patriarchate. The highest hierarchical, canonical and dogmatical authority of the Romanian Orthodox Church is the Holy Synod.

There are six Orthodox Metropolitanates and ten archbishoprics in Romania, and more than twelve thousand priests and deacons, servant fathers of ancient altars from parishes, monasteries and social centres. Almost 400 monasteries exist inside the country, staffed by some 3,500 monks and 5,000 nuns. Three Diasporan Metropolitanates and two Diasporan Bishoprics function outside Romania proper. As of 2004, there are, inside Romania, fifteen theological universities where more than ten thousand students (some of them from Bessarabia, Bukovina and Serbia benefiting from a few Romanian fellowships) currently study for a theological degree. More than 14,500 churches (traditionally named "lăcașe de cult", or houses of worship) exist in Romania for the Romanian Orthodox believers. As of 2002, almost 1,000 of those were either in the process of being built or rebuilt.

Relations with other Orthodox jurisdictions

Canonical Eastern Orthodox autocephalous churches, including the Romanian Orthodox Church, maintain a respectful spiritual link to the Ecumenical Patriarch, currently Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople.

Notable theologians

Dumitru Stăniloae (1903–1993) is considered one of the greatest Orthodox theologians of the 20th century, having written extensively in all major fields of Eastern Christian systematic theology. One of his other major achievements in theology is the 45-year-long comprehensive series on Orthodox spirituality known as the Romanian Philokalia, a collection of texts written by classical Byzantine writers, that he edited and translated from Greek.

Archimandrite Cleopa Ilie (1912–1998), elder of the Sihăstria Monastery, is considered one of the most representative fathers of contemporary Romanian Orthodox monastic spirituality.[29]

List of Patriarchs

- Miron (1925–1939)

- Nicodim (1939–1948)

- Justinian (1948–1977)

- Iustin (1977–1986)

- Teoctist (1986–2007)

- Daniel (since 2007)

Current leaders

The patriarchal chair is currently held by Daniel I, Archbishop of Bucharest, Metropolitan of Muntenia and Dobrudja (former Ungro-Wallachia) and Patriarch of All of the Romanian Orthodox Church. Since 1776, the Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia has been titular bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia (Locțiitor al tronului Cezareei Capadociei), an honor bestowed by Ecumenical Patriarch Sophronius II.[30][31]

- Teofan Savu, Metropolitan of Moldavia and Bukovina[32]

- Laurențiu Streza, Metropolitan of Transylvania[33]

- Andrei Andreicuț, Metropolitan of Cluj, Maramureș and Sălaj

- Nicolae Corneanu, Metropolitan of Banat

- Irineu Popa, Metropolitan of Oltenia

- Petru Păduraru, Metropolitan of Bessarabia

- Iosif Pop, Metropolitan of Western and Southern Europe[34]

- Serafim Joantă, Metropolitan of Germany and Central Europe

- Nicolae Condrea, Metropolitan of the Americas

Gallery

Orthodox cathedral in Galați

Orthodox cathedral in Galați Orthodox cathedral in Mioveni

Orthodox cathedral in Mioveni Orthodox church in Sârbi Josani

Orthodox church in Sârbi Josani

.jpg) Romano-Gothic Orthodox church in Densuș

Romano-Gothic Orthodox church in Densuș Baroque Orthodox cathedral in Lugoj

Baroque Orthodox cathedral in Lugoj Orthodox church in Curtea de Argeș

Orthodox church in Curtea de Argeș

Orthodox church in Vânători-Neamț

Orthodox church in Vânători-Neamț

Orthodox church in Călimănești-Căciulata

Orthodox church in Călimănești-Căciulata Neoclassic Byzantine Orthodox cathedral in Chișinău

Neoclassic Byzantine Orthodox cathedral in Chișinău.jpg) The Palace of the Romanian Patriarchate (the former Palace of the Assembly of Deputies

The Palace of the Romanian Patriarchate (the former Palace of the Assembly of Deputies New Holy Trinity Cathedral of Arad, the first cathedral to be built after the Romanian Revolution

New Holy Trinity Cathedral of Arad, the first cathedral to be built after the Romanian Revolution Romanian People's Salvation Cathedral, Bucharest (under construction)

Romanian People's Salvation Cathedral, Bucharest (under construction) Orthodox church in Gura Humorului, Romania

Orthodox church in Gura Humorului, Romania Orthodox church in Căpriana, Republic of Moldova

Orthodox church in Căpriana, Republic of Moldova Orthodox cathedral in Alba Iulia

Orthodox cathedral in Alba Iulia Orthodox cathedral in Cluj-Napoca

Orthodox cathedral in Cluj-Napoca

See also

- Romanian People’s Salvation Cathedral

- Patriarch of All Romania

- List of Romanian Orthodox monasteries

- Romanian Orthodox icons

- Frumușeni Mosaics

- Byzantium after Byzantium

- Religion in Romania

- Orthodox Church of France

- Orthodox Church in America Romanian Episcopate

- List of members of the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church

- Religious education in Romania

Notes

- ↑ 2011 Romanian census.

- 1 2 (in Romanian) "Biserica Ortodoxă Română, atacată de bisericile 'surori'" ("The Romanian Orthodox Church, Attacked by Its 'Sister' Churches", Ziua, 31 January 2008

- ↑ Krindatch, Alexei (2011). Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-935317-23-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reichel, Walter; Eder, Thomas (2011). "Religions in Austria". Federal Press Service. Vienna: Federal Chancery, Federal Press Service. p. 25. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ 2011 census data on religion

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, Rumania 1866-1947, Clarendon Press, 1994, p. 92

- ↑ Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, pp. 446-447 (2006). "Raport final" (PDF) (in Romanian). Romanian Presidency.

- ↑ Mihail Neamțu (2007-10-17). "Despărțirea apelor: Biserica și Securitatea" (in Romanian). Revista 22.

- ↑ Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, p. 453 (2006). "Raport final" (PDF) (in Romanian). Romanian Presidency.

- ↑ Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, pp. 455-56 (2006). "Raport final" (PDF) (in Romanian). Romanian Presidency.

- ↑ See George Enache. "Biserica Ortodoxă Română și Securitatea" (in Romanian). Ziua.

- 1 2 Ramet, Pedro and Ramet, Sabrina P. Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics, p.19-20. Duke University Press (1989), ISBN 0-8223-0891-6.

- 1 2 3 Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, Religion and Politics in Post-communist Romania, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-530853-0.

- ↑ Maclear, J. F. (1995). Church and State in the Modern Age: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. p. 485. ISBN 9780195086812.

Though Romania's Uniates and The Lord's Army—the evangelical wing of Romanian Orthodoxy—were suppressed in 1948 and other religious groups experienced persecution during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Romania relaxed tensions during the 1970s and acquired a reputation in the West for successful management of religion without marked ruthlessness or violence.

- 1 2 3 Sabrina P. Ramet, "Church and State in Romania before and after 1989", in Carey, Henry F. Romania Since 1989: Politics, Economics, and Society, p.278. 2004, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-0592-2.

- 1 2 Ramet 1989, p.20.

- ↑ Ramet 2004, p. 279.

- ↑ Ramet 2004, p.280.

- ↑ <Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu. The Romanian Orthodox Church and Post-Communist Democratisation. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 52, No. 8 (Dec., 2000), pp. 1467-1488>

- ↑ <Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu. Politics, National Symbols and the Romanian Orthodox Cathedral. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 58, No. 7 (Nov., 2006), pp. 1119-1139>

- ↑ <Ediger, Ruth M. "History of an institution as a factor for predicting church institutional behavior: the cases of the Catholic Church in Poland, the Orthodox Church in Romania, and the Protestant churches in East Germany." East European Quarterly 39.3 (2005)>

- ↑ <Ediger, Ruth M. "History of an institution as a factor for predicting church institutional behavior: the cases of the Catholic Church in Poland, the Orthodox Church in Romania, and the Protestant churches in East Germany." East European Quarterly 39.3 (2005)>

- ↑ Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu. The Romanian Orthodox Church and Post-Communist Democratisation. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 52, No. 8 (Dec., 2000), pp. 1467-1488>

- ↑ A world survey of religion and the state, By Jonathan Fox, pg. 167

- ↑ "International Religious Freedom - Embassy of the United States Bucharest, Romania". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "BBC News - Romania's costly passion for building churches". BBC News. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Law and religion in post-communist Europe By Silvio Ferrari, W. Cole Durham, Elizabeth A. Sewell pg.253

- ↑ "The Romanian Greek-Catholic Community is facing a cultural and religious wipe-out – letter to US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton". HotNewsRo. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Electronic version of Dicționarul teologilor români (Dictionary of Romanian Theologians), Univers Enciclopedic Ed., Bucharest, 1996, retrieved from http://biserica.org/WhosWho/DTR/I/IlieCleopa.html.

- ↑ Mihai Țipău, Paschalis Kitromilides, Domnii fanarioti în Țările Române 1711-1821: mică encyclopedia, p.89. Editura Omonia, 2004, ISBN 978-9738-31917-2

- ↑ Petre Semen, Liviu Petcu, Părinții Capadocieni, p.635. Editura Fundației Academice AXIS, Iași, 2009, ISBN 978-973-7742-80-3

- ↑ Metropolis of Moldavia and Bukovina

- ↑ Metropolis of Transylvania

- ↑ Metropolis of Paris

External links

- Romanian Patriarchate

- The Metropolitanate of Moldavia and Bucovina and the Archdiocese of Iași

- (in Romanian) Boscorodirea

- Archdiocese of Bucharest

- (in Romanian) Portal Ortodox Românesc

- (in Romanian) Romanian Patriarchs

- Pilgrimage Centre in Iași, Romania

- Article on the Romanian Orthodox Church by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA website

Outside Romania

- Moldova: Government Fails in Bessarabian Church Appeal

- Metropolitan Church of Bessarabia and Others v. Moldova

- (in French) Romanian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Western and Southern Europe

- (in Romanian)/(in German) Romanian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Germany and Central Europe

- (in Romanian)/(in French) Romanian Church of Paris

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Romanian Orthodox Church. |