East St. Louis riots

| East St. Louis riots | |

|---|---|

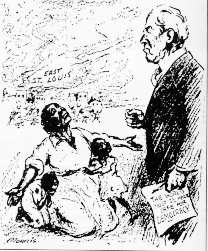

Political cartoon about the East St. Louis massacres of 1917. The caption reads, "Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?", referring to Wilson's catch-phrase "The world must be made safe for democracy" (depicted on the document he holds). | |

| Date | May 28 and July 2, 1917 |

| Location | East St. Louis, Illinois |

| Caused by | White mobs inflamed over labor inequities, beat, shot and lynched African Americans |

| Methods | Rioting, lynching, pogrom |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | at least 40 African Americans[1] |

The East St. Louis riots, or East St. Louis massacres, of May and July 1917 were an outbreak of labor- and race-related violence that caused the death of at least 40 Black people and approximately $400,000 in property damage[1] (over $8 million, in 2017 US Dollars [2] ). The events took place in East St. Louis, Illinois, an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from St. Louis, Missouri. They have been described as the worst case of labor-related violence in 20th-century American history,[3] and among the worst race riots in U.S. history. The local Chamber of Commerce called for the resignation of the police chief. At the end of July, some 10,000 people marched in silent protest in New York City in condemnation of the riots.

Background

In 1917 the United States had an active economy boosted by World War I. With many would-be workers absent for active service in the war, industries were in need of labor. Seeking better work and living opportunities, as well as an escape from harsh conditions, the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South toward industrial centers across the northern and midwestern United States was well underway. For example, blacks were arriving in St. Louis during Spring 1917 at the rate of 2,000 per week.[4] When industries became embroiled in labor strikes, traditionally white unions sought to strengthen their bargaining position by hindering or excluding black workers, while industry owners utilizing blacks as replacements or strikebreakers added to the deep existing societal divisions.[5] The Springfield race riot of 1908 was an expression of the simmering tensions in the region during the nadir of race relations.

While in New Orleans on a lecture tour, black leader Marcus Garvey became aware that Louisiana farmers and the Board of Trade were worried about losing their labor force, and had requested East St. Louis Mayor Mollman's assistance during his New Orleans visit that same week to help discourage black migration.[4]

With many blacks finding work at the Aluminum Ore Company and the American Steel Company in East St. Louis, some whites feared job and wage insecurity due to this new competition; they further resented newcomers arriving from a rural and very different culture. Tensions between the groups escalated, including rumors of black men and white women fraternizing at a labor meeting on May 28.[6][7]

Riots

Following the May 28 meeting, some 3,000 white men marched into downtown East St. Louis and began attacking African Americans. With mobs destroying buildings and beating people, the governor of Illinois called in the National Guard to prevent further rioting. Although rumors circulated about organized retribution attacks from blacks,[6] conditions eased somewhat for a few weeks.

Following the May disorders, the East St. Louis Central Labor Council requested an investigation by the State Council of Defense in which they implied that "southern negroes were misled by false advertisements and unscrupulous employment agents to come to East St. Louis in such numbers under false pretenses of secure jobs and decent living quarters".[8] The tensions between black workers and white workers quickly formed again as no solution to their economic challenges were agreed upon.

On July 2, a car occupied by white males drove through a black area of the city and fired several shots into a standing group. An hour later, a car containing four people, including a journalist and two police officers (Detective Sergeant Samuel Coppedge and Detective Frank Wadley) were passing through the same area. Black residents, possibly assuming they were the original suspects, opened fire on their car, killing one officer instantly and mortally wounding another.[6][9] Later that day, thousands of white spectators who assembled to view the detectives' bloodstained automobile marched into the black section of town and started rioting.[10] After cutting the water hoses of the fire department, the rioters burned entire sections of the city and shot inhabitants as they escaped the flames.[6] Claiming that "Southern negros deserve[d] a genuine lynching,"[11] they lynched several blacks. Guardsmen were called in but accounts exist that they joined in the rioting rather than stopping it.[12][13] More joined in, including allegedly "ten or fifteen young girls about 18 years old, [who] chased a negro woman at the Relay Depot at about 5 o'clock. The girls were brandishing clubs and calling upon the men to kill the woman."[6][14] After the riots, the St. Louis Argus said, "The entire country has been aroused to a sense of shame and pity by the magnitude of the national disgrace enacted by the blood-thirsty rioters in East St. Louis Monday, July 2."[15]

Police response

According to the Post-Dispatch of St. Louis, "All the impartial witnesses agree that the police were either indifferent or encouraged the barbarities, and that the major part of the National Guard was indifferent or inactive. No organized effort was made to protect the Negroes or disperse the murdering groups. The lack of frenzy and of a large infuriated mob made the task easy. Ten determined officers could have prevented most of the outrages. One hundred men acting with authority and vigor might have prevented any outrage."[16]

Aftermath

Death toll

After the riots, varying estimates of the death toll circulated. The police chief estimated that 100 African-Americans had been killed.[4] The renowned journalist Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40–150 African-American people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis.[13][17] The NAACP estimated deaths at 100–200. Six thousand African-Americans were left homeless after their neighborhood was burned. A Congressional Investigating Committee concluded that no precise death toll could be determined, but reported that at least 8 whites and 39 African-Americans died.[18] While the coroner specified nine white deaths, the deaths of African-American victims were less clearly recorded. Activists who disputed the Committee's conclusion, argued that the true number of deaths would never be known because many corpses were not recovered, or did not pass through the hands of undertakers.[19]

The black community's reaction

The ferocious brutality of the attacks and the refusal to protect innocent lives, by the authorities, contributed to the radicalization of many blacks in St. Louis and the nation.[20] Marcus Garvey declared in an speech that the riot was "one of the bloodiest outrages against mankind" and a "wholesale massacre of our people", insisting that "This is no time for fine words, but a time to lift one's voice against the savagery of a people who claim to be the dispensers of democracy."[4][21]

In New York City on July 28, ten thousand black people marched down Fifth Avenue in a Silent Parade, protesting the East St. Louis riots. They carried signs that highlighted protests about the riots. The march was organized by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), W. E. B. Du Bois, and groups in Harlem. Women and children were dressed in white; the men were dressed in black.[20]

The business community's reaction

On July 6, representatives of the Chamber of Commerce met with the mayor to demand the resignation of the Police Chief and Night Police Chief, or radical reform. They were outraged about the rioting and accused the mayor of having allowed a "reign of lawlessness." In addition to the riots taking the lives of too many innocent people, mobs had caused extensive property damage. The Southern Railway Company's warehouse was burned, with over 100 car loads of merchandise, at a loss to the company of over $525,000; a white theatre valued at more than $100,000, was also destroyed.[4] 44 freight cars and 312 houses were destroyed.[22]

Government reaction

In a mass meeting in Carnegie Hall, Samuel Gompers, the president of the American Federation of Labor, attempted to diminish the role that trade unions played in the massacre by persisting that an investigation was needed in order to place blame, "Why don't you accuse after an investigation?" To which the former president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, responded by saying, "Mr. Gompers, why don't I accuse afterwards? I'll answer now, when murder is to be answered." Roosevelt reportedly went on to say, "I will go to the extreme to bring justice to the laboring man, but when there is murder I will put him down."[23]

In a July 28, 1917, letter addressed to Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer, a representative from a St.Louis, Missouri district, President Woodrow Wilson stated that special agents of the Department of Justice could not find enough evidence to justify federal action in the matter, stating: "I am informed that the attorney general of the State of Illinois has gone to East St. Louis to add his efforts to those of the officials of the county and city in pressing prosecutions under the State laws. The representatives of the Department of Justice are so far as possible lending aid to the State authorities in their efforts to restore tranquility and guard against further outbreaks."

Hearings before the Committee on Rules and House of Representatives, 65th Congress began on August 3, 1917. A federal investigation was eventually opened and among those brought to trial was Dr. LeRoy Bundy, a black dentist and prominent leader in the East St. Louis black community, who was formally charged with inciting a riot. Trial was held in the St. Clair county court, Bundy along with thirty-four defendants, of which ten were white, were given prison time in connection to the riot.[24]

References

- 1 2 "The NEGRO SILENT PROTEST PARADE organized by the NAACP Fifth Ave., New York City July 28, 1917" (PDF). National Humanities Center, Research Triangle Park, NC. National Humanities Center. 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Calculate the value of $400,000 in 1917". www.dollartimes.com.

- ↑ Fitch, Solidarity for Sale, 2006, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Speech by Marcus Garvey, July 8, 1917". Excerpts from Robert A. Hill, ed. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Volume I, 1826 – August 1919. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983, accessed 1 February 2009, PBS, American Experience.

- ↑ Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia, New York: Verso, 1998, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rudwick, Race Riot at East St. Louis, 1964.

- ↑ Leonard, "E. St. Louis Riot", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 13, 2004.

- ↑ Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 6, 1917.

- ↑ "Detective Sergeant Samuel Coppedge", Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ↑ Buescher, John. "East St. Louis Massacre." Teachinghistory.org. Accessed July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Heaps, "Target of Prejudice: The Negro", in Riots, USA 1765–1970, p. 114.

- ↑ Gibson, The Negro Holocaust: Lynching and Race Riots in the United States, 1880–1950, 1979.

- 1 2 Patrick, "The Horror of the East St. Louis Massacre", Exodus, February 22, 2000.

- ↑ "Race Rioters Fire East St. Louis and Shoot or Hang Many Negroes", The New York Times, July 3, 1917.

- ↑ "Negroes Did Not Start Trouble". The St. Louis Argus. July 6, 1917. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ↑ St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 5, 1917.

- ↑ Wells, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, rev. ed., 1991.

- ↑ Congressional Edition, Volume 7444, House of Representatives 65th Congress 2nd Session document # 1231, 1918.

- ↑ Elliott M. Rudwick, Race Riot at East St. Louis, July 2, 1917, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1964, p. 50.

- 1 2 James (1998), Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia, p. 96.

- ↑ Herbert Shapiro, White Violence and Black Response: From Reconstruction to Montgomery, University of Massachusetts Press, 1988, p. 163.

- ↑ Congressional Edition, Volume 7444, House of Representatives 65th Congress 2nd Session document # 1231, 1918, pp. 1, 6.

- ↑ Cresco plain dealer. (Cresco, Howard County, Iowa), July 13, 1917. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ↑ The Chicago Daily Tribune, March 29, 1917.

Sources

- Barnes, Harper. Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement, New York: Walker & Company, June 24, 2008. ISBN 0-8027-1575-3.

- Fitch, Robert. Solidarity for Sale. Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Books Group, 2006. ISBN 1-891620-72-X.

- Gibson, Robert A. The Negro Holocaust: Lynching and Race Riots in the United States, 1880–1950. New Haven: Yale University, 1979.

- Heaps, Willard A. "Target of Prejudice: The Negro", In Riots, USA 1765–1970. New York: The Seabury Press, 1970.

- Leonard, Mary Delach. "E. St. Louis Riot." St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 13, 2004.

- Lumpkins, Charles L. "American Pogrom: The East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics." Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8214-1802-4, ISBN 0-8214-1802-5.

- McLaughlin, Malcolm. "Power, Community, and Racial Killing in East St. Louis." New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 1-4039-7078-5.

- McLaughlin, Malcolm. "Reconsidering the East St Louis Race Riot of 1917", International Review of Social History. 47:2 (August 2002).

- "Race Rioters Fire East St. Louis and Shoot or Hang Many Negroes". The New York Times. July 3, 1917.

- Patrick, James. "The Horror of the East St. Louis Massacre." Exodus. February 22, 2000.

- Rudwick, Elliott M. Race Riot at East St. Louis. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 1964.

- Wells, Ida B. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Rev. edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. ISBN 0-226-89344-8.

External links

- The Crisis Magazine, August 1917 report on East St Louis Riot, pp. 177–178.

- The Crisis Magazine, September 1917, pp. 219–237, report on the East St Louis riot

- The Crisis Magazine, April 1922, pp. 17–22.

- "Primary Sources: The Conspiracy Of The East St. Louis Riots", The American Experience. PBS.com.

- "Useful readings on the Riots compiled by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville's Institute For Urban Research

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch coverage of the East St. Louis riot series of archive articles, photos, map, and oral readings on the centennial from June 27 to July 3, 2017.

- Tim O'Neil, "Look Back: Worker struggles, racial hatred in East St. Louis explodes in white rioting", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 1, 2012, and "Worker struggles, racial hatred in East St. Louis explodes in white rioting", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 21, 2014.

- Riot at East St. Louis, Illinois : hearings before the Committee on Rules, House of Representatives, Sixty-fifth Congress, first session, on H.J. res. 118, August 3, 1917