East Prussian plebiscite 1920

The East Prussia(n) plebiscite[1][2] (German: Abstimmung in Ostpreußen), also known as the Allenstein and Marienwerder plebiscite[3][4][5] or Warmia, Masuria and Powiśle plebiscite[6] (Polish: Plebiscyt na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu), was a plebiscite for self-determination of the regions southern Warmia (Ermland), Masuria (Mazury, Masuren) and Powiśle, which had been in parts of the East Prussian Government Region of Allenstein and of West Prussian Government Region of Marienwerder, in accordance with Articles 94 to 97 of the Treaty of Versailles.

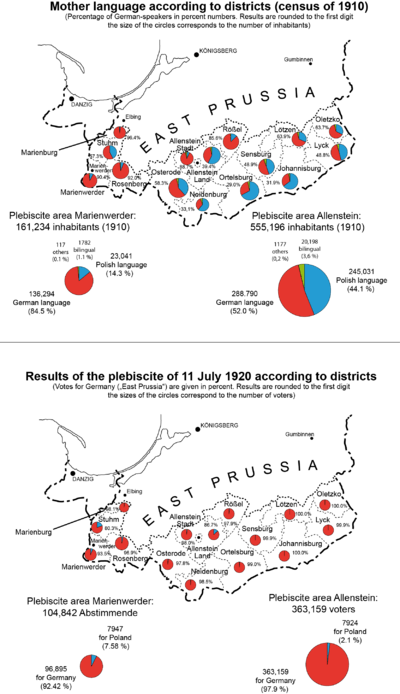

Prepared during early 1920, it took place on 11 July 1920. The plebiscite was conducted by German authorities.[7] According to Richard K. Debo, both German and Polish governments believed that the outcome of the plebiscite was decided by the ongoing Polish-Bolshevik War which threatened the existence of the newly formed Polish state itself and, as a result, even many German citizens of Polish ethnicity of the region voted for Germany out of fear that if the area was allocated to Poland it would soon fall under Soviet rule.[8]

According to several Polish sources the German side engaged in mass persecution of Polish activists, their Masurian supporters, going as far as engaging in regular hunts and murder against them to influence the vote. Additionally the organisation of the plebiscite was influenced by Great Britain, which at the time supported Germany, fearing the increased power of France in post-war Europe.[9][10][11][12][13]

According to Jerzy Minakowski due to terror and unequal status of German and Polish side, Poles boycotted the preparations for the plebiscite which allowed Germans to engage in falsifications.[14] The German conducted plebiscite reported that majority of voters selected East Prussia over Poland (over 97% in the Allenstein Plebiscite Area and 92% in the Marienwerder Plebiscite Area[15]); most of the territories in question remained in the Free State of Prussia, and therefore, in Germany.

Historical background

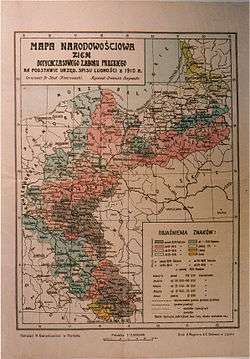

The area concerned had changed hands at various times over the centuries between Old Prussians, Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, Duchy of Prussia, Germany, and Poland. The area of Warmia was part of the Kingdom of Prussia since the first partition of Poland in 1772 and the region of Masuria was ruled by the German Hohenzollern family since the Prussian Tribute of 1525 (as a Polish fief till 1660). Many inhabitants of that region had Polish roots and were influenced by Polish culture; the last official German census in 1910 classified them ethnically as Poles or Masurians.[16]) During the period of the German Empire, harsh Germanisation measures were enacted in the region.[17] The Polish delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, led by Roman Dmowski, made a number of demands in relation to those areas which were part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1772 and despite their protests, supported by the French, President Woodrow Wilson and the other allies agreed that plebiscites according to self-determination should be held.[18] In the former German Province of Posen and parts of West Prussia an armed revolt had already removed the German authorities in 1919.

Plebiscite areas

The plebiscite areas[19] (German: Abstimmungsgebiete; French: zones du plébiscite) were placed under the authority of two Inter-Allied Commissions of five members appointed by the Principal Allied and Associated Powers representing the League of Nations. British and Italian troops under the command of these Commissions had arrived on and soon after February 12, 1920. The regular German Reichswehr had previously left the precincts of the plebiscite. Civil and municipal administration was continued under the existing German authorities who were responsible to the Commissions for their duration.[20]

In accordance with Articles 94 to 97 of the Treaty of Versailles (section entitled "East Prussia"[21]) the Marienwerder Plebiscite Area was formed from northeastern parts of the Marienwerder Government Region (based in Marienwerder in West Prussia, now Kwidzyn) encompassing the Districts of Marienwerder (east of the Vistula), of Stuhm (based in Stuhm, present Sztum), of Rosenberg in West Prussia (based in Rosenberg in West Prussia, present Susz) as well as parts of Marienburg in West Prussia (based in Marienburg in West Prussia, Malbork, part of the Danzig Government Region) east of the Nogat.[22] The treaty defined the Allenstein Plebiscite Area as "The western and northern boundary of Allenstein Government Region to its junction with the boundary between the districts of Oletzko (based in Marggrabowa, now Olecko) and of Angerburg (based in Angerburg, now Węgorzewo); thence, the northern boundary of the Oletzko District to its junction with the old frontier of East Prussia."[21] Thus the Allenstein precinct comprised all the Allenstein Region plus the Oletzko District (Gumbinnen Government Region).

According to Jerzy Minakowski the area of the plebiscite was inhabited by 720,000 people, German citizens, of whom 440,000 were ethnically Polish.[23] The official Prussian census of 1910 showed 245,000 Polish-speakers and 289,000 German-speakers in the Allenstein Government Region and 23,000 versus 136,000 in the Marienwerder Government Region.[24]

Allenstein / Olsztyn Plebiscite Area

The Allied forces had to intervene in this precinct already in 1919 to release imprisoned Masurians, who tried to reach the Paris conference.[25]

The President of and British Commissioner on the Inter-Allied Administrative and Plebiscite Commission for Allenstein was Mr. Ernest Rennie; French Commissioner was M. Couget; the Marquis Fracassi, a Senator, for Italy; Mr. Marumo for Japan. The German Government were permitted under the Protocol terms to attach a delegate and they sent Reichskommissar Wilhelm von Gayl, formerly in the service of the Interior Ministry and lately on the Inner Colonisation Committee. The local police forces were placed under the control of two British officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Bennet and Major David Deevis. Bennet reported that he regarded them as "well-disciplined and reliable". There was also present a battalion from the Royal Irish Regiment and an Italian regiment stationed at Lyck (Ełk).[26] According to Jerzy Minakowski those small forces had proven themselves inadequate to protect pro-Polish voters in the precincts from pro-German repressions.[27]

This Commission had general powers of administration and, in particular, was "charged with the duty of arranging for the vote and of taking such measures as it may deem necessary to ensure its freedom, fairness, and secrecy. The Commission will have all necessary authority to decide any questions to which the execution of these provisions may give rise. The Commission will make such arrangements as may be necessary for assistance in the exercise of its functions by officials chosen by itself from the local population. Its decisions will be taken by a majority." The commission was welcomed by ethnic Poles in the region, who hoped that their situation would improve due to its presence,[28] however, petitions were made to remove German officials and the Sicherheitswehr,[29] while demanding that the official welcoming committee made up from German officials should show the representatives of the Allies the plight of ethnic Polish population.[29] On 18 February 1919 the Allenstein-based Commission decreed that the Polish language would gain equal rights to the German language in the region.[30]

The Commission had to eventually remove both the mayor of Allenstein, Georg Zülch, and an officer of Sicherheitswehr, Major Oldenburg, after a Polish banner at the local consulate of Poland was defaced; the Polish side expressed gratitude for Allied protection of Polish rights and underlined its desire for peaceful coexistence with German-speaking population.[31]

In April 1920 during a Polish theatrical performance in Deuthen (Dajtki) near Allenstein, ethnic Poles were attacked by pro-German activists; on the demands of the Allied Commission, the German police escorted Polish actors but ignored the attackers.[32] In Bischofsburg (Biskupiec) a pogrom against ethnic Poles was organised, which prompted the creation of a special commission to find the perpetrators.[33] The Allensteiner Zeitung newspaper called on its readers to remain calm and cease pogroms against ethnic Poles, pointing out that it could lead to postponing the plebiscite which would go against German interests.[34] Italian forces were sent to Lötzen (Giżycko), according to Jerzy Minakowski to protect the ethnic Polish population, after a pogrom happened there on 17 April.[35] In May several attacks on ethnic Poles were reported in Osterode (Ostróda), and included attacks on co-workers of the Masurian Committee.[36]

Marienwerder / Kwidzyn Plebiscite Area

Parts of the Marienwerder Government Region were confined as the Marienwerder Plebiscite Area. The British commissioner Henry Beaumont and the other members of the Commission for the plebiscite area reached Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) on February 17, 1920. Upon their arrival they found an Italian battalion of Bersaglieri on guard who afterwards marched past at the double. This commission had about 1,400 uniformed German police under its authority.[37] Beaumont soon became known for his cold and ironic attitude to the Poles and his hostility to the Polish cause[38]

Beaumont said that with the exception of the Kreis Stuhm, where ethnic Poles admittedly numbered 15,500 out of a population of 36,500 (42%), the German sympathies of the inhabitants were clearly evident. He reported that ethnic Poles were strictly guarding the frontier, thus preventing people from passing without vexatious formalities. According to Beaumont trains were held up for hours or the service completely suspended, postal, telegraphic and telephonic communication constantly interrupted. The great bridge over the Vistula at Dirschau was barred by sentries (in French uniforms) "who refuse to understand any language but Polish". As a result, Beaumont writes, this area was "cut off from its shopping centre and chief port almost completely". To Beaumont it would be "desirable to convey a hint to the Warsaw Government that their present policy is scarcely calculated to gain them votes."[39]

Sir Horace Rumbold, the British Minister in Warsaw, also wrote to Curzon on March 5, 1920, saying that the Plebiscite Commissions at Allenstein and Marienwerder "felt that they were isolated both from Poland and from Germany" and that the Polish authorities were holding up supplies of coal and petrol to those districts. Sir Horace had a meeting with the Polish Minister for Foreign Affairs, M. Patek, who declared he was disappointed with his people's behaviour and "spoke strongly about the tactlessness and rigidity of the Polish Military authorities."[40]

On March 10, 1920, Beaumont wrote of numerous continuing difficulties being made by Polish officials and stressed the "ill-will between Polish and German nationalities and the irritation due to Polish intolerance towards the German inhabitants in the Corridor (now under their rule), far worse than any former German intolerance of the Poles, are growing to such an extent that it is impossible to believe the present settlement (borders) can have any chance of being permanent..."[41]

The Poles began to harden their position and Rumbold reported to Curzon on March 22, 1920 that Count Stefan Przeździecki, an official of the Polish Foreign Office, had told Sir Percy Loraine (1st Secretary in H.M. Legation at Warsaw) that the Poles questioned the impartiality of the Inter-Allied Commissions and indicated that the Polish Government might refuse to recognise the results of the Plebiscites.[42]

Propaganda

German "Heimatdienst"

Both sides started a propaganda campaign. Already in March 1919 Paul Hensel, the Lutheran Superintendent of Johannisburg, travelled to Versailles to hand over a collection of 144,447 signatures to the Allied Powers to protest against the planned cession.[43] Pro-German campaigners founded several regional associations under the title of the "Ostdeutscher Heimatdienst" (i.e. East German Homeland Service), which had over 220,000 members.[43] The Heimatdienst in the region was led by Max Worgitzki, an author and publisher of the "Ostdeutsche Nachrichten".

The Heimatdienst exerted enormous psychological pressure on Masurians to vote for Germany, and threatened pro-Polish forces with physical violence.[44] They put their emphasis on Prussian history and loyalty to the Prussian state and also used prejudices against Polish culture and Poland's alleged economical backwardness.[45] Rennie, the British Commissioner in Allenstein, reported on March 11, 1920, that "in those parts which touch the Polish frontier a vigorous German propaganda is in progress", and that "the Commission is doing all it can to prevent German officials in the district from taking part in national propaganda in connection with the Plebiscite. Ordinances and instructions in this sense have been issued."[46] The pro-German side informed the local population that in event of a pro-Polish victory all men will be drafted into Polish military to fight against Soviet Russia.[47]

Polish campaign

A delegation of Masurians petitioned the Allies in March 1919 to join their region with Poland.[48]

The Poles established an unofficial Masurian Plebiscite Committee (Mazurski Komitet Plebiscytowy) on June 6, 1919 under the chairmanship of the Polish citizen Juliusz Bursche, later Bishop of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland. There was also an unofficial Warmian Plebiscite Committee. They argued that the Masurians of Warmia (Ermland) and Masuria were victims of a long period of Germanisation, but ethnic Poles, now had the opportunity to liberate themselves from Prussian rule.[49]

Rennie reported to Curzon at the British Foreign Office, on February 18, 1920, that the Poles, who had taken control of the Polish Corridor to the Baltic Sea, had "entirely disrupted the railway, telegraphic and telephone system, and the greatest difficulty is being experienced."[50]

Rennie reported on March 11, 1920, that the Polish Consul-General, Dr. Zenon Lewandowski, aged about 60 and a former chemist who kept a shop in Poznań (Posen), had arrived. Rennie describes Lewandowski as having "little experience of official life". According to Rennie Lewandowski began to send complaints to the Commission immediately after his arrival, in which he declared that the entire ethnically Polish population of this district had been terrorised for years and, as a result, was unable to express their sentiments. Rennie reports an incident as Lewandowski repeatedly hoisted the Polish flag at the consular office which caused protests of the population. Rennie "pointed out to Dr. Lewandowski that he ought to realise that his position here was a delicate one........and I added it was highly desirable that his office should not be situated in a building with the Bureau of Polish propaganda."[51]

Undercover and illicit activities were also commenced and as early as March 11, 1920 the Earl of Derby reported a decision of the Allied Council of Ambassadors in Paris to make representations to the Polish government regarding violations of the frontiers of the Marienwerder Plebiscite Area by Polish soldiers.[52]

Beaumont reported from Marienwerder at the end of March that "no change has been made in the methods of Polish propaganda. Occasional meetings are held, but they are attended only by Poles in small numbers." He continues "acts and articles violently abusive of everything German in the newly founded Polish newspaper appear to be the only (peaceful) methods adopted to persuade the inhabitants of the Plebiscite areas to vote for Poland."[53]

The German side tried to sway the voters in the area before the plebiscite using violence, Polish organisations and activists were harassed by pro-German militias, and those actions included murder; the most notable example being the killing of Bogumił Linka a native Masurian member of the Polish delegation to Versailles, who supported vote for Poland; his death described as "bestial murder", after being brutally beaten by pro-German militias armed with crowbars, metal rods, and shovels, his ribs were punctured by shovel, only barely alive and bleeding additionally from neck and head, he was taken to hospital where he died.[54][55] After his burial the grave of Linka was defiled.[56]

Masurians who supported voting for Poland were singled out and subjected to terror and repressions.[57] Names of Masurians supporting the Polish side were published in pro-German newspapers, and their photos presented in shops of pro-German owners; afterwards regular hunts were organised after them.[58] In the pursuit of Polish supporters the local Polish population was terrorised by pro-German militias[59] Local "Gazeta Olsztyńska" wrote "Unspeakable terror lasted till the last days [of the plebiscite]"[60] At least 3,000 Warmian and Masurian activists who were engaged for the Polish side had to flee the region out of fear of their lives.[61] German police engaged in active surveillance of Polish minority and attacks against pro-Polish activists.[62]

The plebiscite

The plebiscites asked the voters whether they wanted their homeland to remain in East Prussia (or become a part of it, as to the Marienwerder Plebiscite Area), which was part of Weimar Germany, or instead become part of Poland (the alternatives for the voters were not Poland / Germany, but Poland / East Prussia, which itself was no sovereign nation). All inhabitants of the plebiscite areas older than 20 years of age or those who were born in this area before 1 January 1905, were entitled to return to vote.

Reproaches of falsification and manipulation

According to Jerzy Minakowski before the plebiscite pro-Polish activists decided to boycott the preparations for electoral commissions to protest unequal treatment of the Polish and German side and pro-German terror, this allowed German officials to falsify lists with eligible voters, writing down names of dead people or people who weren't eligible to vote.[63] During the plebiscite Germans transported pro-German voters to numerous locations allowing them to cast votes multiple times.[64] In Allenstein (Olsztyn) cards with pro-Polish votes were simply taken away by a German official who declared that they were "invalid" and presented voters with cards for the pro-German side.[64] Voters were observed by German police in polling stations.[64] Pro-Polish voting cards were often hidden or taken away[64] and Polish controllers were removed from polling stations[64] A large number of ethnic Poles - out of fear of repressions - didn't attend the plebiscite[64]

Results

The plebiscite took place on 11 July 1920; at the time Poland appeared on the verge of defeat in the Polish-Soviet War (see Miracle at the Vistula). The pro-German side was able to organise a very successful propaganda campaign, building on the long campaign of Germanisation; notably the plebiscite asking the electorate to vote for Poland or East Prussia masked the pro-German choice under the regional name of Prussia. The activity of pro-German organisations, and the Allied support for the participation of Masurians who were born in Masuria but did not live there any longer, further aided the German cause. Hence the plebiscite ended with a majority of the voters voting for East Prussia, only a small part of the territory affected by the plebiscite was awarded to Poland, with the majority remaining with Germany.[65]

After the vote, the Poles felt disadvantaged by the Versailles Treaty stipulation which enabled those who were born in the plebiscite areas but not living there any more to return to vote. Approximately 152,000 such individuals participated in the plebiscite.[66] There is confusion on whether this was a Polish or German condition at Versailles as it might have been expected that many Ruhr Area Poles would vote for Poland.[49] While it is reported, that the Polish delegation planned to bring Polish émigrés not only from other parts of Germany but also from America to the plebiscite area to strengthen their position,[67] the Polish delegation claimed that it was a German condition.

After the plebiscite in German areas of Masuria attacks on ethnic Polish population commenced by pro-German mobs and ethnically Polish priests and politicians were driven from their homes.[68]

Results as published by Poland[15] thus giving also Polish place names as fixed in the late 1940s.

Olsztyn/Allenstein Plebiscite Area

The results for Olsztyn/Allenstein Plebiscite Area were:[15][69]

| District | Capital (present name) | Region | votes for East Prussia (in total) |

votes for Poland (in total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allenstein, urban district | (Olsztyn) | Allenstein | 98% (16,742) | 2% (342) |

| Allenstein, rural district | Allenstein (Olsztyn) | Allenstein | 86.68% (31,707) | 13.32% (4,871) |

| Johannisburg | Johannisburg in East Prussia (Pisz[70]) | Allenstein | 99.96% (33,817) | 0.04% (14) |

| Lötzen | Lötzen (Giżycko[71]) | Allenstein | 99.97% (29,349) | 0.03% (10) |

| Lyck | Lyck (Ełk) | Allenstein | 99.88% (36,573) | 0.12% (44) |

| Neidenburg | Neidenburg (Nidzica[72]) | Allenstein | 98.54% (22,235) | 1.46% (330) |

| Oletzko | Marggrabowa (Olecko) | Gumbinnen | 99.99% (28,625) | 0.01% (2) |

| Ortelsburg | Ortelsburg (Szczytno) | Allenstein | 98.51% (48,207) | 1.49% (497) |

| Osterode in East Prussia | Osterode in East Prussia (Ostróda) | Allenstein | 97.81% (46,368) | 2.19% (1,031) |

| Rößel | Bischofsburg (Biskupiec) | Allenstein | 97.9% (35,248) | 2.1% (758) |

| Sensburg | Sensburg (Mrągowo) | Allenstein | 99.93% (34,332) | 0.07% (25) |

| total % | 97.89% | 2.11% | ||

| total votes | 363,209 | 7,980[73] | ||

| Voter turnout 87,31 %% (371,715) |

registered voters: 425,305, valid: 371,189, turnout: 87.31%

To honour the exceptionally high percentage of pro-German votes in the district of Oletzko, with 2 votes for Poland compared to 28,625 for Germany, the district town Marggrabowa (i.e. Margrave town) was renamed "Treuburg" (TreueGerman = "faithfulness") in 1928,[74] with the district following this example in 1933.

In the villages of Lubstynek (Klein Lobenstein), Czerlin (Klein Nappern) and Groszki (Groschken) in the District of Osterode in East Prussia (Ostróda), situated directly at the border, a majority voted for Poland. These villages became a part of Poland after the plebiscite.[75]

Due to the Prussian Eastern Railway line Danzig-Warsaw passing there, the area of Soldau in the Neidenburg District was transferred to Poland without plebiscite, and renamed Działdowo.

Marienwerder / Kwidzyn Plebiscite Area

The results for the precincts of Marienwerder / Kwidzyn were:[15][76]

| District | Capital (present name) | Region | votes for East Prussia (in total) |

votes for Poland (in total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marienburg in West Prussia | Marienburg in West Prussia (Malbork) | Danzig | 98.94% (17,805) | 1.06% (191) |

| Marienwerder | Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) | Marienwerder | 93.73% (25,608) | 6.27% (1,779) |

| Rosenberg in West Prussia | Rosenberg in West Prussia (Susz) | Marienwerder | 96.9% (33,498) | 3.1% (1,073) |

| Stuhm | Stuhm (Sztum) | Marienwerder | 80.3% (19,984) | 19.7% (4,904) |

| total % | 92.36% | 7.64% | ||

| total votes | 96,923 | 8,018 [77] | ||

| Voter turnout 84% (105,071) |

registered voters: 125,090 valid: 104,941 turnout: 84.00%

The West Prussian plebiscite area remained with Germany and became part of the new East Prussian West Prussia Government Region.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to East Prussian plebiscite. |

- Territorial changes of Germany after World War I

- Territorial changes of Poland after World War I

- Upper Silesia plebiscite

- Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship

Notes

- ↑ Keynes, Google Print, p.11 (full view - text is in PD)

- ↑ Tooley, Google Print, p.176

- ↑ Butler, pps: 720 - 828

- ↑ Williamson, pps: 93-101

- ↑ Wambaugh

- ↑ Topolski, p. 31.

- ↑ Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: history, data, analysis. Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski. page 166, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- ↑ Debo, Richard K. , "Survival and consolidation: the foreign policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921", McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, pg. 335.

- ↑ Zarys dzíejów Polski Jerzy Topolski Interpress,page 204, 1986

- ↑ Rocznik olsztyński: Tom 10 Muzeum Warmii i Mazur w Olsztynie - 1972 - Jeśli chodzi o stanowisko Anglików, to na Powiślu i Mazurach popierali oni wraz z Włochami Niemców,

- ↑ Nowe ksia̜żki: miesie̜cznik krytyki literackiej i naukowej, Tom 857,Wydanie 860 -Tom 862,Wydanie 860 Biblioteka Narodowa (Warszawa)Wiedza Powszechna,page 71, 1990

- ↑ Gospodarka Polski międzywojennej, 1918-1939: Landau, Z., Tomaszewski, J. W dobie inflacji, 1918-1923, Książka i Wiedza, page 24, 1967

- ↑ Historical abstracts: Twentieth century abstracts, 1914-2000: Volume 37 American Bibliographical Center, page 743 - 1986 On 9 March 1920, Germans attacked the Polish consulate in the city of Allenstein (Olsztyn), as part of an anti-Polish campaign preceding the plebiscite East Prussia provided for by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919

- ↑ Minakowski, Jerzy (2010). "Baza artykułów dotyczących plebiscytu na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu w 1920 roku" (PDF) (in Polish). Wojciech Kętrzyński Institute, Olsztyn. p. 15. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Results of a plebiscite in three Polish districts conducted between July 1920 and March 1921. Rocznik statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej link(pdf, 623 KB). Główny Urząd Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej GUS, Annual (Main Statistical Office of the Republic of Poland) (1920/1922, part II). Retrieved on 2008-01-23.

- ↑ Mayer, vol.8, p. 3357-8

- ↑ The many faces of Clio: cross-cultural approaches to historiography, essays in honor of Georg G. Iggers, Edward Wang, Franz L. Fillafer "Border regions,hybridity and national identity-the cases of Alsace and Masuria" Stefan Berger, page 375, Berghahn Books, 2007

- ↑ Mayer, vol.8, p. 3357

- ↑ Terminology used in the Treaty of Versailles, Article 88, annex, first and fourth paragraphs.

- ↑ Butler, p. 722

- 1 2 The Versailles Treaty

- ↑ A map of counties of Marienburg and Marienwerder with marked results of the plebiscite with discussion

- ↑ Minakowski..., page 10, Olsztyn 2010

- ↑ the census results are published in Rocznik statystyki Rzczypospolitej Polskiej/Annuaire statistique de la République Polonaise 1 (1920/22), vol 2, Warszawa 1923, p. 358. pdf

- ↑ Minakowski p.28

- ↑ Butler, p. 721-2 and 731

- ↑ Minakowski p. 11

- ↑ Minakowski p.46

- 1 2 Minakowski p. 47

- ↑ Minakowski p.54

- ↑ Minakowski p. 59

- ↑ Minakowski p. 60

- ↑ Minakowski p. 61

- ↑ Minakowski p.284

- ↑ Minakowski p.61

- ↑ Minakowski p. 65

- ↑ Butler p. 728

- ↑ Dzieło najżywsze z żywch: antologia reportażu o ziemiach zachodnich ; północnych z lat 1919-1939 Witold Nawrocki Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Odnosiło się wrażenie, iż zawzięty, zimny i ironiczny pan Beaumont nie jest wcale przyjacielem naszej sprawy na tej ziemi 1981

- ↑ Butler, p. 723-4

- ↑ Butler, p.725

- ↑ Butler, p.726-7

- ↑ Butler, p.734-5

- 1 2 Andreas Kossert: Ostpreußen. Geschichte und Mythos. München 2005, S. 219

- ↑ The many faces of Clio: cross-cultural approaches to historiography, essays in honor of Georg G. Iggers, Edward Wang, Franz L. Fillafer "Border regions,hybridity and national identity-the cases of Alsace and Masuria" Stefan Berger, page 378, Berghahn Books, 2007

- ↑ Kossert, p.249

- ↑ Butler, p.732 and 743

- ↑ Jan Chłosta Prawda o plebiscytach na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu, Siedlisko, Tom 5, 2008.Instytut Zachodni, Poznań

- ↑ Między Królewcem, Warszawą, Berlinem a Londynem: Wojciech Wrzesiński,Wydawnictw Adam Marszałek page 131, 2001

- 1 2 Kossert, p. 247

- ↑ Butler, p.723

- ↑ Butler, p.730-1

- ↑ Butler, p.729

- ↑ Butler, p.737

- ↑ Kurek Mazurski (in Polish)

- ↑ Bard ziemi mazurskiej Jerzy Oleksiński Nasza Księgarnia,"Niemieccy lekarze ze szpitala w Olsztynie nie udzielili mu natychmiastowej i odpowiedniej pomocy. Postąpili w myśl nieludzkiej zasady, że „umierającemu nie należy przerywać konania" 1976

- ↑ Najnowsza historia Polski 1914-1993 Andrzej Albert, Wojciech Roszkowski Puls, page 95, 1994

- ↑ Problemy narodowościowe w Kościele ewangelickim na Mazurach w latach 1918-1945,page 43 Ryszard Otello, Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im. Wojciecha Kętrzyńskiego w Olsztynie, 2003

- ↑ Szkice z dziejów Pomorza: Pomorze na progu dziejów najnowszych Gerard Labuda,Książka i Wiedza, 1961

- ↑ Historia Polski: 1914-1993 Wojciech Roszkowski Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN 1994:"Podobnie jak na Śląsku, bojówki niemieckie szerzyły wśród ludności polskiej terror".

- ↑ Historia Warmii i Mazur: od pradziejów do 1945 roku, page 251, Stanisław Achremczyk - 1992

- ↑ Kiermasy na Warmii i inne pisma wybrane Walenty Barczewski,page 14 Pojezierze.

- ↑ Plebiscyty na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu w 1920 roku: wybór źródeł, Piotr Stawecki, Wojciech Wrzesiński, Zygmunt Lietz, page 13,Ośrodek badań naukowych 1986

- ↑ Minakowski p.15

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Minakowski p.16

- ↑ Cezary Bazydlo (www.jugendzeit-ostpreussen.de): Plebiscyt 1920 (in Polish), Volksabstimmung 1920 (in German), 2006

- ↑ Rhode, p. 122

- ↑ Tooley, T. Hunt (1997). National identity and Weimar Germany. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Kazimierz Jaroszyk, 1878-1941: o narodowy kształt Warmii i Mazur. Wydawnictwo Pojezierze,page 89, 1986

- ↑ Butler, p. 826

- ↑ Jańsbork between 1945-1946.

- ↑ Lec between 1945-1946.

- ↑ Nibork between 1945-1946.

- ↑ Suchmaschine für direkte Demokratie: Allenstein / Olsztyn (Ostpreussen), 11. Juli 1920

- ↑ Adrian Room, Place-name Changes Since 1900: A World Gazetteer

- ↑ Kossert, p.247

- ↑ Butler, p. 806

- ↑ Suchmaschine für direkte Demokratie: Marienwerder / Kwidzyn (Westpreussen), 11. Juli 1920

References

- Butler, Rohan, MA., Bury, J.P.T.,MA., & Lambert M.E., MA., editors, Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, 1st Series, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1960, vol.x, Chapter VIII, "The Plebiscites in Allenstein and Marienwerder January 21 - September 29, 1920"

- Keynes, John Maynard. A Revision of the Treaty: Being a Sequel to The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Harcourt, Brace, 1922

- Kossert, Andreas. Masuren: Ostpreussens vergessener Süden, ISBN 3-570-55006-0 (in German)

- Mayer, S. L., MA. History of the First World War – Plebiscites:Self Determination in Action, Peter Young, MA., editor, BPC Publishing Ltd., UK., 1971.

- Rhode, Gotthold. Die Ostgebiete des Deutschen Reiches, Holzner-Verlag Würzburg, 1956.

- Tooley, T. Hunt. National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918-1922, U of Nebraska Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8032-4429-0

- Topolski, Jerzy. An Outline History of Poland, Interpress, 1986, ISBN 83-223-2118-X

- Wambaugh, Sarah. Plebiscites since the World War, Washington DC, 1933. I p 99 – 141; II p 48 - 107

- Williamson, David G. The British in Germany 1918-1930, Oxford, 1991, ISBN 0-85496-584-X

Further reading

- Robert Kempa, Plebiscyt 1920 r. w północno-wschodniej części Mazur (na przykładzie powiatu giżyckiego). In Masovia. Pismo poświęcone dziejom Mazur, 4/2001, Giżycko 2001, p. 149-157 (in Polish)

- Andreas Kossert, Ostpreussen: Geschichte und Mythos, ISBN 3-88680-808-4 (in German)

- Andreas Kossert, Religion versus Ethnicity: A Case Study of Nationalism or How Masuria Became a "Borderland", in: Madeleine Hurd (ed.): Borderland Identities: Territory and Belonging in Central, North and East Europe. Eslöv 2006, S.313-330

- Adam Szymanowicz, Udział Oddziału II Sztabu Generalnego Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych w pracach plebiscytowych na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu w 1920 roku. In Komunikaty Mazursko - Warmińskie, 4/2004, p. 515 - 530.(in Polish)

- Wojciech Wrzesiñsk, Das Recht zur Selbstbestimmung oder der Kampf um staatliche Souveränität - Plebiszit in Ostpreußen 1920 in AHF Informationen Nr. 54 vom 20.09.2000 (in German)

External links

- 1920 map showing German territory's changes, including marked area for the East Prussia plebiscite

- Mapa powiatów malborskiego i kwidzynskiego z naniesionymi przedstawieniami wyników plebiscytu sporządzona 11 VII 1920

- Map of interwar Poland; shows plebiscite areas

- Map of interwar Poland; shows plebiscite areas (in color) (in Polish)

- Małe ząbkowane - czyli rzecz o kwidzynskich znaczkach plebiscytowych i nie tylko (in Polish)

Karsten, Carl (1922). "Allenstein-Marienwerder". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).

Karsten, Carl (1922). "Allenstein-Marienwerder". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).