Satellite

| Part of a series on |

| Spaceflight |

|---|

|

| History |

| Applications |

| Spacecraft |

| Launch |

| Destinations |

| Space agencies |

| Private spaceflight |

|

|

In context of spaceflight, a satellite is an artificial object which has been intentionally placed into orbit. Such objects are sometimes called artificial satellites to distinguish them from natural satellites such as Earth's Moon.

In 1957 the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1. Since then, about 6,600 satellites from more than 40 countries have been launched. According to a 2013 estimate, 3,600 remained in orbit.[1] Of those, about 1,000 were operational;[2] while the rest have lived out their useful lives and became space debris. Approximately 500 operational satellites are in low-Earth orbit, 50 are in medium-Earth orbit (at 20,000 km), and the rest are in geostationary orbit (at 36,000 km).[3] A few large satellites have been launched in parts and assembled in orbit. Over a dozen space probes have been placed into orbit around other bodies and become artificial satellites to the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, a few asteroids,[4] and the Sun.

Satellites are used for many purposes. Common types include military and civilian Earth observation satellites, communications satellites, navigation satellites, weather satellites, and space telescopes. Space stations and human spacecraft in orbit are also satellites. Satellite orbits vary greatly, depending on the purpose of the satellite, and are classified in a number of ways. Well-known (overlapping) classes include low Earth orbit, polar orbit, and geostationary orbit.

A launch vehicle is a rocket that throws a satellite into orbit. Usually it lifts off from a launch pad on land. Some are launched at sea from a submarine or a mobile maritime platform, or aboard a plane (see air launch to orbit).

Satellites are usually semi-independent computer-controlled systems. Satellite subsystems attend many tasks, such as power generation, thermal control, telemetry, attitude control and orbit control.

History

Early conceptions

"Newton's cannonball", presented as a "thought experiment" in A Treatise of the System of the World, by Isaac Newton was the first published mathematical study of the possibility of an artificial satellite.

The first fictional depiction of a satellite being launched into orbit was a short story by Edward Everett Hale, The Brick Moon.[5][6] The idea surfaced again in Jules Verne's The Begum's Fortune (1879).

In 1903, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) published Exploring Space Using Jet Propulsion Devices (in Russian: Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами), which is the first academic treatise on the use of rocketry to launch spacecraft. He calculated the orbital speed required for a minimal orbit, and that a multi-stage rocket fuelled by liquid propellants could achieve this.

In 1928, Herman Potočnik (1892–1929) published his sole book, The Problem of Space Travel — The Rocket Motor (German: Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums — der Raketen-Motor). He described the use of orbiting spacecraft for observation of the ground and described how the special conditions of space could be useful for scientific experiments.

In a 1945 Wireless World article, the English science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008) described in detail the possible use of communications satellites for mass communications.[7] He suggested that three geostationary satellites would provide coverage over the entire planet.

The US military studied the idea of what was referred to as the earth satellite vehicle when Secretary of Defense James Forrestal made a public announcement on 29 December 1948, that his office was coordinating that project between the various services.[8]

Artificial satellites

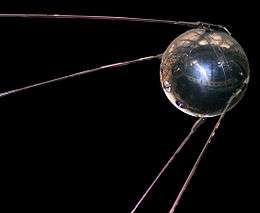

The first artificial satellite was Sputnik 1, launched by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957, and initiating the Soviet Sputnik program, with Sergei Korolev as chief designer. This in turn triggered the Space Race between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Sputnik 1 helped to identify the density of high atmospheric layers through measurement of its orbital change and provided data on radio-signal distribution in the ionosphere. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1's success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in the United States and ignited the so-called Space Race within the Cold War.

Sputnik 2 was launched on 3 November 1957 and carried the first living passenger into orbit, a dog named Laika.[9]

In May, 1946, Project RAND had released the Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship, which stated, "A satellite vehicle with appropriate instrumentation can be expected to be one of the most potent scientific tools of the Twentieth Century."[10] The United States had been considering launching orbital satellites since 1945 under the Bureau of Aeronautics of the United States Navy. The United States Air Force's Project RAND eventually released the report, but considered the satellite to be a tool for science, politics, and propaganda, rather than a potential military weapon. In 1954, the Secretary of Defense stated, "I know of no American satellite program."[11] In February 1954 Project RAND released "Scientific Uses for a Satellite Vehicle," written by R.R. Carhart.[12] This expanded on potential scientific uses for satellite vehicles and was followed in June 1955 with "The Scientific Use of an Artificial Satellite," by H.K. Kallmann and W.W. Kellogg.[13]

In the context of activities planned for the International Geophysical Year (1957–58), the White House announced on 29 July 1955 that the U.S. intended to launch satellites by the spring of 1958. This became known as Project Vanguard. On 31 July, the Soviets announced that they intended to launch a satellite by the fall of 1957.

Following pressure by the American Rocket Society, the National Science Foundation, and the International Geophysical Year, military interest picked up and in early 1955 the Army and Navy were working on Project Orbiter, two competing programs: the army's which involved using a Jupiter C rocket, and the civilian/Navy Vanguard Rocket, to launch a satellite. At first, they failed: initial preference was given to the Vanguard program, whose first attempt at orbiting a satellite resulted in the explosion of the launch vehicle on national television. But finally, three months after Sputnik 2, the project succeeded; Explorer 1 became the United States' first artificial satellite on 31 January 1958.[14]

In June 1961, three-and-a-half years after the launch of Sputnik 1, the Air Force used resources of the United States Space Surveillance Network to catalog 115 Earth-orbiting satellites.[15]

Early satellites were constructed as "one-off" designs. With growth in geosynchronous (GEO) satellite communication, multiple satellites began to be built on single model platforms called satellite buses. The first standardized satellite bus design was the HS-333 GEO commsat, launched in 1972.

The largest artificial satellite currently orbiting the Earth is the International Space Station.

Space Surveillance Network

The United States Space Surveillance Network (SSN), a division of the United States Strategic Command, has been tracking objects in Earth's orbit since 1957 when the Soviet Union opened the Space Age with the launch of Sputnik I. Since then, the SSN has tracked more than 26,000 objects. The SSN currently tracks more than 8,000 man-made orbiting objects. The rest have re-entered Earth's atmosphere and disintegrated, or survived re-entry and impacted the Earth. The SSN tracks objects that are 10 centimeters in diameter or larger; those now orbiting Earth range from satellites weighing several tons to pieces of spent rocket bodies weighing only 10 pounds. About seven percent are operational satellites (i.e. ~560 satellites), the rest are space debris.[16] The United States Strategic Command is primarily interested in the active satellites, but also tracks space debris which upon reentry might otherwise be mistaken for incoming missiles.

Non-military satellite services

There are three basic categories of non-military satellite services:[17]

Fixed satellite services

Fixed satellite services handle hundreds of billions of voice, data, and video transmission tasks across all countries and continents between certain points on the Earth's surface.

Mobile satellite systems

Mobile satellite systems help connect remote regions, vehicles, ships, people and aircraft to other parts of the world and/or other mobile or stationary communications units, in addition to serving as navigation systems.

Scientific research satellites (commercial and noncommercial)

Scientific research satellites provide meteorological information, land survey data (e.g. remote sensing), Amateur (HAM) Radio, and other different scientific research applications such as earth science, marine science, and atmospheric research.

Types

- Astronomical satellites are satellites used for observation of distant planets, galaxies, and other outer space objects.

- Biosatellites are satellites designed to carry living organisms, generally for scientific experimentation.

- Communications satellites are satellites stationed in space for the purpose of telecommunications. Modern communications satellites typically use geosynchronous orbits, Molniya orbits or Low Earth orbits.

- Earth observation satellites are satellites intended for non-military uses such as environmental monitoring, meteorology, map making etc. (See especially Earth Observing System.)

- Navigational satellites are satellites which use radio time signals transmitted to enable mobile receivers on the ground to determine their exact location. The relatively clear line of sight between the satellites and receivers on the ground, combined with ever-improving electronics, allows satellite navigation systems to measure location to accuracies on the order of a few meters in real time.

- "Killer Satellites" are satellites that are designed to destroy enemy warheads, satellites, and other space assets.

- Crewed spacecraft (spaceships) are large satellites able to put humans into (and beyond) an orbit, and return them to Earth. Spacecraft including spaceplanes of reusable systems have major propulsion or landing facilities. They can be used as transport to and from the orbital stations.

- Miniaturized satellites are satellites of unusually low masses and small sizes.[18] New classifications are used to categorize these satellites: minisatellite (500–100 kg), microsatellite (below 100 kg), nanosatellite (below 10 kg).

- Reconnaissance satellites are Earth observation satellite or communications satellite deployed for military or intelligence applications. Very little is known about the full power of these satellites, as governments who operate them usually keep information pertaining to their reconnaissance satellites classified.

- Recovery satellites are satellites that provide a recovery of reconnaissance, biological, space-production and other payloads from orbit to Earth.

- Space stations are artificial orbital structures that are designed for human beings to live on in outer space. A space station is distinguished from other crewed spacecraft by its lack of major propulsion or landing facilities. Space stations are designed for medium-term living in orbit, for periods of weeks, months, or even years.

- Tether satellites are satellites which are connected to another satellite by a thin cable called a tether.

- Weather satellites are primarily used to monitor Earth's weather and climate.[19]

Orbit types

The first satellite, Sputnik 1, was put into orbit around Earth and was therefore in geocentric orbit. By far this is the most common type of orbit with approximately 1,459[20] artificial satellites orbiting the Earth. Geocentric orbits may be further classified by their altitude, inclination and eccentricity.

The commonly used altitude classifications of geocentric orbit are Low Earth orbit (LEO), Medium Earth orbit (MEO) and High Earth orbit (HEO). Low Earth orbit is any orbit below 2,000 km. Medium Earth orbit is any orbit between 2,000 and 35,786 km. High Earth orbit is any orbit higher than 35,786 km.

Centric classifications

- Geocentric orbit: An orbit around the planet Earth, such as the Moon or artificial satellites. Currently there are approximately 1,459[20] artificial satellites orbiting the Earth.

- Heliocentric orbit: An orbit around the Sun. In our Solar System, all planets, comets, and asteroids are in such orbits, as are many artificial satellites and pieces of space debris. Moons by contrast are not in a heliocentric orbit but rather orbit their parent planet.

- Areocentric orbit: An orbit around the planet Mars, such as by moons or artificial satellites.

The general structure of a satellite is that it is connected to the earth stations that are present on the ground and connected through terrestrial links.

Altitude classifications

- Low Earth orbit (LEO): Geocentric orbits ranging in altitude from 180 km - 2,000 km (1,200 mi)

- Medium Earth orbit (MEO): Geocentric orbits ranging in altitude from 2,000 km (1,200 mi) - 35,786 km (22,236 mi). Also known as an intermediate circular orbit.

- Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO): Geocentric circular orbit with an altitude of 35,786 kilometres (22,236 mi). The period of the orbit equals one sidereal day, coinciding with the rotation period of the Earth. The speed is approximately 3,000 metres per second (9,800 ft/s).

- High Earth orbit (HEO): Geocentric orbits above the altitude of geosynchronous orbit 35,786 km (22,236 mi).

Inclination classifications

- Inclined orbit: An orbit whose inclination in reference to the equatorial plane is not zero degrees.

- Polar orbit: An orbit that passes above or nearly above both poles of the planet on each revolution. Therefore, it has an inclination of (or very close to) 90 degrees.

- Polar sun synchronous orbit: A nearly polar orbit that passes the equator at the same local time on every pass. Useful for image taking satellites because shadows will be nearly the same on every pass.

Eccentricity classifications

- Circular orbit: An orbit that has an eccentricity of 0 and whose path traces a circle.

- Hohmann transfer orbit: An orbit that moves a spacecraft from one approximately circular orbit, usually the orbit of a planet, to another, using two engine impulses. The perihelion of the transfer orbit is at the same distance from the Sun as the radius of one planet's orbit, and the aphelion is at the other. The two rocket burns change the spacecraft's path from one circular orbit to the transfer orbit, and later to the other circular orbit. This maneuver was named after Walter Hohmann.

- Elliptic orbit: An orbit with an eccentricity greater than 0 and less than 1 whose orbit traces the path of an ellipse.

- Geosynchronous transfer orbit: An elliptic orbit where the perigee is at the altitude of a Low Earth orbit (LEO) and the apogee at the altitude of a geosynchronous orbit.

- Geostationary transfer orbit: An elliptic orbit where the perigee is at the altitude of a Low Earth orbit (LEO) and the apogee at the altitude of a geostationary orbit.

- Molniya orbit: A highly elliptic orbit with inclination of 63.4° and orbital period of half of a sidereal day (roughly 12 hours). Such a satellite spends most of its time over two designated areas of the planet (specifically Russia and the United States).

- Tundra orbit: A highly elliptic orbit with inclination of 63.4° and orbital period of one sidereal day (roughly 24 hours). Such a satellite spends most of its time over a single designated area of the planet.

Synchronous classifications

- Synchronous orbit: An orbit where the satellite has an orbital period equal to the average rotational period (earth's is: 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.091 seconds) of the body being orbited and in the same direction of rotation as that body. To a ground observer such a satellite would trace an analemma (figure 8) in the sky.

- Semi-synchronous orbit (SSO): An orbit with an altitude of approximately 20,200 km (12,600 mi) and an orbital period equal to one-half of the average rotational period (Earth's is approximately 12 hours) of the body being orbited

- Geosynchronous orbit (GSO): Orbits with an altitude of approximately 35,786 km (22,236 mi). Such a satellite would trace an analemma (figure 8) in the sky.

- Geostationary orbit (GEO): A geosynchronous orbit with an inclination of zero. To an observer on the ground this satellite would appear as a fixed point in the sky.[21]

- Clarke orbit: Another name for a geostationary orbit. Named after scientist and writer Arthur C. Clarke.

- Supersynchronous orbit: A disposal / storage orbit above GSO/GEO. Satellites will drift west. Also a synonym for Disposal orbit.

- Subsynchronous orbit: A drift orbit close to but below GSO/GEO. Satellites will drift east.

- Graveyard orbit: An orbit a few hundred kilometers above geosynchronous that satellites are moved into at the end of their operation.

- Disposal orbit: A synonym for graveyard orbit.

- Junk orbit: A synonym for graveyard orbit.

- Geostationary orbit (GEO): A geosynchronous orbit with an inclination of zero. To an observer on the ground this satellite would appear as a fixed point in the sky.[21]

- Areosynchronous orbit: A synchronous orbit around the planet Mars with an orbital period equal in length to Mars' sidereal day, 24.6229 hours.

- Areostationary orbit (ASO): A circular areosynchronous orbit on the equatorial plane and about 17000 km (10557 miles) above the surface. To an observer on the ground this satellite would appear as a fixed point in the sky.

- Heliosynchronous orbit: A heliocentric orbit about the Sun where the satellite's orbital period matches the Sun's period of rotation. These orbits occur at a radius of 24,360 Gm (0.1628 AU) around the Sun, a little less than half of the orbital radius of Mercury.

Special classifications

- Sun-synchronous orbit: An orbit which combines altitude and inclination in such a way that the satellite passes over any given point of the planets' surface at the same local solar time. Such an orbit can place a satellite in constant sunlight and is useful for imaging, spy, and weather satellites.

- Moon orbit: The orbital characteristics of Earth's Moon. Average altitude of 384,403 kilometers (238,857 mi), elliptical–inclined orbit.

Pseudo-orbit classifications

- Horseshoe orbit: An orbit that appears to a ground observer to be orbiting a certain planet but is actually in co-orbit with the planet. See asteroids 3753 (Cruithne) and 2002 AA29.

- Exo-orbit: A maneuver where a spacecraft approaches the height of orbit but lacks the velocity to sustain it.

- Suborbital spaceflight: A synonym for exo-orbit.

- Lunar transfer orbit (LTO)

- Prograde orbit: An orbit with an inclination of less than 90°. Or rather, an orbit that is in the same direction as the rotation of the primary.

- Retrograde orbit: An orbit with an inclination of more than 90°. Or rather, an orbit counter to the direction of rotation of the planet. Apart from those in sun-synchronous orbit, few satellites are launched into retrograde orbit because the quantity of fuel required to launch them is much greater than for a prograde orbit. This is because when the rocket starts out on the ground, it already has an eastward component of velocity equal to the rotational velocity of the planet at its launch latitude.

- Halo orbit and Lissajous orbit: Orbits "around" Lagrangian points.

Satellite subsystems

The satellite's functional versatility is imbedded within its technical components and its operations characteristics. Looking at the "anatomy" of a typical satellite, one discovers two modules.[17] Note that some novel architectural concepts such as Fractionated spacecraft somewhat upset this taxonomy.

Spacecraft bus or service module

The bus module consists of the following subsystems:

Structural subsystem

The structural subsystem provides the mechanical base structure with adequate stiffness to withstand stress and vibrations experienced during launch, maintain structural integrity and stability while on station in orbit, and shields the satellite from extreme temperature changes and micro-meteorite damage.

Telemetry subsystem

The telemetry subsystem (aka Command and Data Handling, C&DH) monitors the on-board equipment operations, transmits equipment operation data to the earth control station, and receives the earth control station's commands to perform equipment operation adjustments.

Power subsystem

The power subsystem consists of solar panels to convert solar energy into electrical power, regulation and distribution functions, and batteries that store power and supply the satellite when it passes into the Earth's shadow. Nuclear power sources (Radioisotope thermoelectric generator have also been used in several successful satellite programs including the Nimbus program (1964–1978).[22]

Thermal control subsystem

The thermal control subsystem helps protect electronic equipment from extreme temperatures due to intense sunlight or the lack of sun exposure on different sides of the satellite's body (e.g. Optical Solar Reflector)

Attitude and orbit control subsystem

The attitude and orbit control subsystem consists of sensors to measure vehicle orientation; control laws embedded in the flight software; and actuators (reaction wheels, thrusters) to apply the torques and forces needed to re-orient the vehicle to a desired attitude, keep the satellite in the correct orbital position and keep antennas positioning in the right directions.

Communication payload

The second major module is the communication payload, which is made up of transponders. A transponder is capable of :

- Receiving uplinked radio signals from earth satellite transmission stations (antennas).

- Amplifying received radio signals

- Sorting the input signals and directing the output signals through input/output signal multiplexers to the proper downlink antennas for retransmission to earth satellite receiving stations (antennas).

End of life

When satellites reach the end of their mission this occurs in 3 or 4 years, satellite operators have the option of de-orbiting the satellite, leaving the satellite in its current orbit or moving the satellite to a graveyard orbit. Historically, due to budgetary constraints at the beginning of satellite missions, satellites were rarely designed to be de-orbited. One example of this practice is the satellite Vanguard 1. Launched in 1958, Vanguard 1, the 4th manmade satellite put in Geocentric orbit, was still in orbit as of August 2009.[23]

Instead of being de-orbited, most satellites are either left in their current orbit or moved to a graveyard orbit.[24] As of 2002, the FCC requires all geostationary satellites to commit to moving to a graveyard orbit at the end of their operational life prior to launch.[25] In cases of uncontrolled de-orbiting, the major variable is the solar flux, and the minor variables the components and form factors of the satellite itself, and the gravitational perturbations generated by the Sun and the Moon (as well as those exercised by large mountain ranges, whether above or below sea level). The nominal breakup altitude due to aerodynamic forces and temperatures is 78 km, with a range between 72 and 84 km. Solar panels, however, are destroyed before any other component at altitudes between 90 and 95 km.[26]

Launch-capable countries

This list includes countries with an independent capability to place satellites in orbit, including production of the necessary launch vehicle. Note: many more countries have the capability to design and build satellites but are unable to launch them, instead relying on foreign launch services. This list does not consider those numerous countries, but only lists those capable of launching satellites indigenously, and the date this capability was first demonstrated. The list includes the European Space Agency, a multi-national state organization, but does not include private consortiums.

| Order | Country | Date of first launch | Rocket | Satellite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | | 4 October 1957 | Sputnik-PS | Sputnik 1 |

| 2 | | 1 February 1958 | Juno I | Explorer 1 |

| 3 | | 26 November 1965 | Diamant-A | Astérix |

| 4 | | 11 February 1970 | Lambda-4S | Ōsumi |

| 5 | | 24 April 1970 | Long March 1 | Dong Fang Hong I |

| 6 | | 28 October 1971 | Black Arrow | Prospero |

| 7 | | 18 July 1980 | SLV | Rohini D1 |

| 8 | | 19 September 1988 | Shavit | Ofeq 1 |

| - [1] | | 21 January 1992 | Soyuz-U | Kosmos 2175 |

| - [1] | | 13 July 1992 | Tsyklon-3 | Strela |

| 9 | | 2 February 2009 | Safir-1 | Omid |

| 10 | | 12 December 2012 | Unha-3 | Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2 |

Attempted first launches

- The United States tried in 1957 to launch the first satellite using its own launcher before successfully completing a launch in 1958.

- China tried in 1969 to launch the first satellite using its own launcher before successfully completing a launch in 1970.

- India, after launching its first national satellite using a foreign launcher in 1975, tried in 1979 to launch the first satellite using its own launcher before succeeding in 1980.

- Iraq have claimed an orbital launch of a warhead in 1989, but this claim was later disproved.[27]

- Brazil, after launching its first national satellite using a foreign launcher in 1985, tried to launch a satellite using its own VLS 1 launcher three times in 1997, 1999, and 2003, but all attempts were unsuccessful.

- North Korea claimed a launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 and Kwangmyŏngsŏng-2 satellites in 1998 and 2009, but U.S., Russian and other officials and weapons experts later reported that the rockets failed to send a satellite into orbit, if that was the goal. The United States, Japan and South Korea believe this was actually a ballistic missile test, which was a claim also made after North Korea's 1998 satellite launch, and later rejected. The first (April 2012) launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 was unsuccessful, a fact publicly recognized by the DPRK. However, the December 2012 launch of the "second version" of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 was successful, putting the DPRK's first confirmed satellite into orbit.

- South Korea (Korea Aerospace Research Institute), after launching their first national satellite by foreign launcher in 1992, unsuccessfully tried to launch its own launcher, the KSLV (Naro)-1, (created with the assistance of Russia) in 2009 and 2010 until success was achieved in 2013 by Naro-3.

- The First European multi-national state organization ELDO tried to make the orbital launches at Europa I and Europa II rockets in 1968–1970 and 1971 but stopped operation after failures.

Other notes

- ^ Russia and the Ukraine were parts of the Soviet Union and thus inherited their launch capability without the need to develop it indigenously. Through the Soviet Union they are also on the number one position in this list of accomplishments.

- France, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine launched their first satellites by own launchers from foreign spaceports.

- Some countries such as South Africa, Spain, Italy, Germany, Canada, Australia, Argentina, Egypt and private companies such as OTRAG, have developed their own launchers, but have not had a successful launch.

- Only twelve, countries from the list below (USSR, USA, France, Japan, China, UK, India, Russia, Ukraine, Israel, Iran and North Korea) and one regional organization (the European Space Agency, ESA) have independently launched satellites on their own indigenously developed launch vehicles.

- Several other countries, including Brazil, Argentina, Pakistan, Romania, Taiwan, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Turkey and Switzerland are at various stages of development of their own small-scale launcher capabilities.

Launch capable private entities

- Private firm Orbital Sciences Corporation, with launches since 1982, continues very successful launches of its Minotaur, Pegasus, Taurus and Antares rocket programs.

- On 28 September 2008, late comer and private aerospace firm SpaceX successfully launched its Falcon 1 rocket into orbit. This marked the first time that a privately built liquid-fueled booster was able to reach orbit.[31] The rocket carried a prism shaped 1.5 m (5 ft) long payload mass simulator that was set into orbit. The dummy satellite, known as Ratsat, will remain in orbit for between five and ten years before burning up in the atmosphere.[31]

A few other private companies are capable of sub-orbital launches.

First satellites of countries

While Canada was the third country to build a satellite which was launched into space,[49] it was launched aboard an American rocket from an American spaceport. The same goes for Australia, who launched first satellite involved a donated U.S. Redstone rocket and American support staff as well as a joint launch facility with the United Kingdom.[50] The first Italian satellite San Marco 1 launched on 15 December 1964 on a U.S. Scout rocket from Wallops Island (Virginia, United States) with an Italian launch team trained by NASA.[51] By similar occasions, almost all further first national satellites was launched by foreign rockets.

Attempted first satellites

United States tried unsuccessfully to launch its first satellite in 1957; they were successful in 1958.

United States tried unsuccessfully to launch its first satellite in 1957; they were successful in 1958. China tried unsuccessfully to launch its first satellite in 1969; they were successful in 1970.

China tried unsuccessfully to launch its first satellite in 1969; they were successful in 1970. Iraq under Saddam Hussein fulfilled in 1989 an unconfirmed launch of warhead on orbit by developed Iraqi vehicle that intended to put later the 75 kg first national satellite Al-Ta’ir, also developed.[52][53]

Iraq under Saddam Hussein fulfilled in 1989 an unconfirmed launch of warhead on orbit by developed Iraqi vehicle that intended to put later the 75 kg first national satellite Al-Ta’ir, also developed.[52][53] Chile tried unsuccessfully in 1995 to launch its first satellite FASat-Alfa by foreign rocket; in 1998 they were successful.†

Chile tried unsuccessfully in 1995 to launch its first satellite FASat-Alfa by foreign rocket; in 1998 they were successful.† North Korea has tried in 1998, 2009, 2012 to launch satellites, first successful launch on 12 December 2012.[54]

North Korea has tried in 1998, 2009, 2012 to launch satellites, first successful launch on 12 December 2012.[54].svg.png) Libya since 1996 developed its own national Libsat satellite project with the goal of providing telecommunication and remote sensing services[55] that was postponed after the fall of Gaddafi.

Libya since 1996 developed its own national Libsat satellite project with the goal of providing telecommunication and remote sensing services[55] that was postponed after the fall of Gaddafi. Belarus tried unsuccessfully in 2006 to launch its first satellite BelKA by foreign rocket.†

Belarus tried unsuccessfully in 2006 to launch its first satellite BelKA by foreign rocket.†

†-note: Both Chile and Belarus used Russian companies as principal contractors to build their satellites, they used Russian-Ukrainian manufactured rockets and launched either from Russia or Kazakhstan.

Planned first satellites

Afghanistan announced in April 2012 that it is planning to launch its first communications satellite to the orbital slot it has been awarded. The satellite Afghansat 1 was expected to be obtained by a Eutelsat commercial company in 2014.[56][57]

Afghanistan announced in April 2012 that it is planning to launch its first communications satellite to the orbital slot it has been awarded. The satellite Afghansat 1 was expected to be obtained by a Eutelsat commercial company in 2014.[56][57] Angola will have the first telecommunication satellite AngoSat-1 that was ordered in Russia at 2009 for $400 millions, started to construction at the end of 2013 and planning for launch in November 2016.[58]

Angola will have the first telecommunication satellite AngoSat-1 that was ordered in Russia at 2009 for $400 millions, started to construction at the end of 2013 and planning for launch in November 2016.[58] Armenia in 2012 founded Armcosmos company[59] and announced an intention to have the first telecommunication satellite ArmSat. The investments estimates as $250 million and country selecting the contractor for building within 4 years the satellite amongst Russia, China and Canada[60][61][62]

Armenia in 2012 founded Armcosmos company[59] and announced an intention to have the first telecommunication satellite ArmSat. The investments estimates as $250 million and country selecting the contractor for building within 4 years the satellite amongst Russia, China and Canada[60][61][62] Bangladesh announced in 2009 that it intends to launch its first satellite into space by 2011.[63]

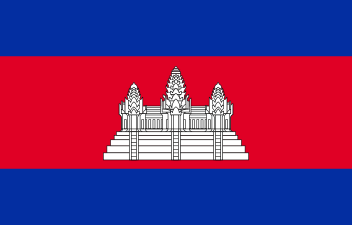

Bangladesh announced in 2009 that it intends to launch its first satellite into space by 2011.[63] Cambodia's Royal Group plans to purchase for $250–350 million and launch in the beginning of 2013 the telecommunication satellite.[64]

Cambodia's Royal Group plans to purchase for $250–350 million and launch in the beginning of 2013 the telecommunication satellite.[64] Democratic Republic of the Congo ordered at November 2012 in China (Academy of Space Technology (CAST) and Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC)) the first telecommunication satellite CongoSat-1 which will be built on DFH-4 satellite bus platform and will be launched in China till the end of 2015.[65]

Democratic Republic of the Congo ordered at November 2012 in China (Academy of Space Technology (CAST) and Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC)) the first telecommunication satellite CongoSat-1 which will be built on DFH-4 satellite bus platform and will be launched in China till the end of 2015.[65] Croatia has a goal to construct a satellite by 2013–2014. Launch into Earth orbit would be done by a foreign provider.[66]

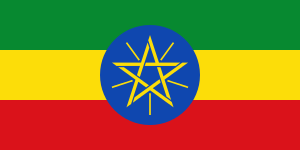

Croatia has a goal to construct a satellite by 2013–2014. Launch into Earth orbit would be done by a foreign provider.[66] Ethiopian Space Science Society[67] planning the QB50-family research CubeSat ET-SAT by help of Belgian Von Karman Institute till 2015[68] and the small (20–25 kg) Earth observation and remote sensing satellite Ethosat 1 by help of Finnish Space Technology and Science Group till 2019.[69]

Ethiopian Space Science Society[67] planning the QB50-family research CubeSat ET-SAT by help of Belgian Von Karman Institute till 2015[68] and the small (20–25 kg) Earth observation and remote sensing satellite Ethosat 1 by help of Finnish Space Technology and Science Group till 2019.[69] Ghana plans to order in United Kingdom and Italy and launch within 2020 the first Earth observation satellite Ghanasat-1.[70]

Ghana plans to order in United Kingdom and Italy and launch within 2020 the first Earth observation satellite Ghanasat-1.[70] Ireland's team of Dublin Institute of Technology intends to launch the first Irish satellite within European University program CubeSat QB50.[71]

Ireland's team of Dublin Institute of Technology intends to launch the first Irish satellite within European University program CubeSat QB50.[71] Jordan's first satellite to be the private amateur pocketqube SunewnewSat.[72][73][74]

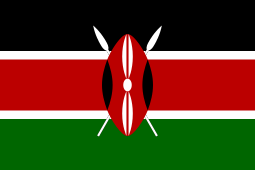

Jordan's first satellite to be the private amateur pocketqube SunewnewSat.[72][73][74] Kenyan University of Nairobi has plans to create the microsatellite KenyaSat by help of UK's University of Surrey.[75]

Kenyan University of Nairobi has plans to create the microsatellite KenyaSat by help of UK's University of Surrey.[75] Latvia's the 5 kg nano-satellite Venta-1 is built in Latvia in cooperation with the German engineers. The data received from satellite will be received and processed in Irbene radioastronomical centre (Latvia); satellite will have software defined radio capabilities. "Venta-1" will serve mainly as a means for education in Ventspils University College with additional functions, including an automatic system of identification of the ships of a sailing charter developed by OHB-System AG. The launch of the satellite was planned for the end of 2009 using the Indian carrier rocket. Due to the financial crisis the launch has been postponed until late 2011.[76] Started preparations to produce the next satellite "Venta-2". "Venta-1" started 23.06.2017. with Indian launche vehicle PSLV-XL[77]

Latvia's the 5 kg nano-satellite Venta-1 is built in Latvia in cooperation with the German engineers. The data received from satellite will be received and processed in Irbene radioastronomical centre (Latvia); satellite will have software defined radio capabilities. "Venta-1" will serve mainly as a means for education in Ventspils University College with additional functions, including an automatic system of identification of the ships of a sailing charter developed by OHB-System AG. The launch of the satellite was planned for the end of 2009 using the Indian carrier rocket. Due to the financial crisis the launch has been postponed until late 2011.[76] Started preparations to produce the next satellite "Venta-2". "Venta-1" started 23.06.2017. with Indian launche vehicle PSLV-XL[77] Moldova's first remote sensing satellite plans to start in 2013 by Space centre at national Technical University.[78]

Moldova's first remote sensing satellite plans to start in 2013 by Space centre at national Technical University.[78] Mongolia's National Remote Sensing Center of Mongolia plans to order the communication satellite in Japan, Mongolian Academy of Sciences schedules to launch the first national experimental satellite Mongolsat by US launcher in the first quarter of 2013.[79]

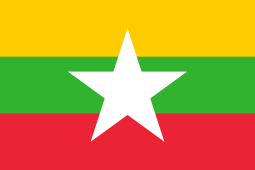

Mongolia's National Remote Sensing Center of Mongolia plans to order the communication satellite in Japan, Mongolian Academy of Sciences schedules to launch the first national experimental satellite Mongolsat by US launcher in the first quarter of 2013.[79] Myanmar plans to purchase for $200 million the own telecommunication satellite.[80]

Myanmar plans to purchase for $200 million the own telecommunication satellite.[80] Nepal stated that planning to launch of own telecommunication satellite before 2015 by help of India or China.[81][82][83]

Nepal stated that planning to launch of own telecommunication satellite before 2015 by help of India or China.[81][82][83] New Zealand's private Satellite Opportunities company since 2005 plans to launch in 2010 or later a commercial satellite NZLSAT for $200 million.[84] Radio enthusiasts federation at Massey University since 2003 hopes for $400,000 to launch a nano-satellite KiwiSAT to relay a voice and data signals[85] Also another RocketLab company works under suborbital space launcher and may use a further version of one to launch into low polar orbit a nano-satellite.[86][87]

New Zealand's private Satellite Opportunities company since 2005 plans to launch in 2010 or later a commercial satellite NZLSAT for $200 million.[84] Radio enthusiasts federation at Massey University since 2003 hopes for $400,000 to launch a nano-satellite KiwiSAT to relay a voice and data signals[85] Also another RocketLab company works under suborbital space launcher and may use a further version of one to launch into low polar orbit a nano-satellite.[86][87] Nicaragua ordered for $254 million at November 2013 in China the first telecommunication satellite Nicasat-1 (to be built at DFH-4 satellite bus platform by CAST and CGWIC), that planning to launch in China at 2016.[88]

Nicaragua ordered for $254 million at November 2013 in China the first telecommunication satellite Nicasat-1 (to be built at DFH-4 satellite bus platform by CAST and CGWIC), that planning to launch in China at 2016.[88] Paraguay under new Aaepa airspace agency plans first Eart observation satellite.[89][90]

Paraguay under new Aaepa airspace agency plans first Eart observation satellite.[89][90] Serbia's first satellite Tesla-1 was designed, developed and assembled by nongovermental organisations in 2009 but still remains unlaunched.

Serbia's first satellite Tesla-1 was designed, developed and assembled by nongovermental organisations in 2009 but still remains unlaunched. Slovakian Organisation for Space Activities (SOSA)[91] together with University of Žilina and Slovak University of Technology developing the first national satellite SkCube[92] under European University program CubeSat QB50 since 2012 aiming to launch them in 2016.[93]"skCUBE" started 23.06.2017. with Indian launche vehicle PSLV-XL[94]

Slovakian Organisation for Space Activities (SOSA)[91] together with University of Žilina and Slovak University of Technology developing the first national satellite SkCube[92] under European University program CubeSat QB50 since 2012 aiming to launch them in 2016.[93]"skCUBE" started 23.06.2017. with Indian launche vehicle PSLV-XL[94] Slovenia's Earth observation microsatellite for the Slovenian Centre of Excellence for Space Sciences and Technologies (Space-SI) now under development for $2 million since 2010 by University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies – Space Flight Laboratory (UTIAS – SFL) and planned to launch in 2015–2016.[95][96]

Slovenia's Earth observation microsatellite for the Slovenian Centre of Excellence for Space Sciences and Technologies (Space-SI) now under development for $2 million since 2010 by University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies – Space Flight Laboratory (UTIAS – SFL) and planned to launch in 2015–2016.[95][96] Sri Lanka has a goal to construct two satellites beside of rent the national SupremeSAT payload in Chinese satellites. Sri Lankan Telecommunications Regulatory Commission has signed an agreement with Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd to get relevant help and resources. Launch into Earth orbit would be done by a foreign provider.[97][98]

Sri Lanka has a goal to construct two satellites beside of rent the national SupremeSAT payload in Chinese satellites. Sri Lankan Telecommunications Regulatory Commission has signed an agreement with Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd to get relevant help and resources. Launch into Earth orbit would be done by a foreign provider.[97][98] Syrian Space Research Center developing CubeSat-like small first national satellite since 2008.[99]

Syrian Space Research Center developing CubeSat-like small first national satellite since 2008.[99] Tunisia is developing its first satellite, ERPSat01. Consisting of a CubeSat of 1 kg mass, it will be developed by the Sfax School of Engineering. ERPSat satellite is planned to be launched into orbit in 2013.[100]

Tunisia is developing its first satellite, ERPSat01. Consisting of a CubeSat of 1 kg mass, it will be developed by the Sfax School of Engineering. ERPSat satellite is planned to be launched into orbit in 2013.[100] Uzbekistan's State Space Research Agency (UzbekCosmos) announced in 2001 about intention of launch in 2002 first remote sensing satellite.[101] Later in 2004 was stated that two satellites (remote sensing and telecommunication) will be built by Russia for $60–70 million each[102]

Uzbekistan's State Space Research Agency (UzbekCosmos) announced in 2001 about intention of launch in 2002 first remote sensing satellite.[101] Later in 2004 was stated that two satellites (remote sensing and telecommunication) will be built by Russia for $60–70 million each[102]

Attacks on satellites

In recent times, satellites have been hacked by militant organizations to broadcast propaganda and to pilfer classified information from military communication networks.[103][104]

For testing purposes, satellites in low earth orbit have been destroyed by ballistic missiles launched from earth. Russia, the United States and China have demonstrated the ability to eliminate satellites.[105] In 2007 the Chinese military shot down an aging weather satellite,[105] followed by the US Navy shooting down a defunct spy satellite in February 2008.[106]

Jamming

Due to the low received signal strength of satellite transmissions, they are prone to jamming by land-based transmitters. Such jamming is limited to the geographical area within the transmitter's range. GPS satellites are potential targets for jamming,[107][108] but satellite phone and television signals have also been subjected to jamming.[109][110]

Also, it is very easy to transmit a carrier radio signal to a geostationary satellite and thus interfere with the legitimate uses of the satellite's transponder. It is common for Earth stations to transmit at the wrong time or on the wrong frequency in commercial satellite space, and dual-illuminate the transponder, rendering the frequency unusable. Satellite operators now have sophisticated monitoring that enables them to pinpoint the source of any carrier and manage the transponder space effectively.

Satellite services

See also

- 2009 satellite collision

- Atmospheric satellite

- Fractionated spacecraft

- Imagery intelligence

- International Designator

- List of communications satellite firsts

- List of Earth observation satellites

- List of passive satellites

- Satellite Catalog Number

- Satellite formation flying

- Satellite watching

- Space exploration

- Space probe

- Spaceport (including list of spaceports)

- Satellites on stamps

- USA-193 (2008 American anti-satellite missile test)

References

- ↑ Rising, David (11 November 2013). "Satellite hits Atlantic — but what about next one?". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12.

- ↑ "Global Experts Agree Action Needed on Space Debris". European Space Agency. 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Cain, Fraser (24 October 2013). "How Many Satellites are in Space?". Universe Today.

- ↑ "NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet". NASA.

- ↑ "Rockets in Science Fiction (Late 19th Century)". Marshall Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2000-09-01. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1991). Science-fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-87338-416-2.

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (2000). Visions of Technology. Simon & Schuster. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-684-86311-5.

- ↑ Corporation, Bonnier (May 1949). "Is US Building A New Moon". Popular Science.

- ↑ Gray, Tara; Garber, Steve (2 August 2004). "A Brief History of Animals in Space". NASA.

- ↑ "Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship". RAND. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Alfred (1968). Venture Into Space: Early Years of Goddard Space Flight Center. NASA. p. 15.

- ↑ R.R. Carhart, Scientific Uses for a Satellite Vehicle, Project RAND Research Memorandum. (Rand Corporation, Santa Monica) 12 February 1954.

- ↑ 2. H.K Kallmann and W.W. Kellogg, Scientific Use of an Artificial Satellite, Project RAND Research Memorandum. (Rand Corporation, Santa Monica) 8 June 1955.

- ↑ Chang, Alicia (30 January 2008). "50th anniversary of first U.S. satellite launch celebrated". SFGate. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ Portree, David S. F.; Loftus, Jr, Joseph P. (1999). "Orbital Debris: A Chronology" (PDF). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2000-09-01. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ "Orbital Debris Education Package" (PDF). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- 1 2 Grant, A.; Meadows, J. (2004). Communication Technology Update (ninth ed.). Focal Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-240-80640-9.

- ↑ "Workshop on the Use of Microsatellite Technologies" (PDF). United Nations. 2008. p. 6. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ↑ "Earth Observations from Space" (PDF). National Academy of Science. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-12.

- 1 2 "UCS Satellite Database". Union of Concerned Scientists. 31 Dec 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Oberg, James (July 1984). "Pearl Harbor In Space". Omni. pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Schmidt, George; Houts, Mike (16 February 2006). "Radioisotope-based Nuclear Power Strategy for Exploration Systems Development" (PDF). STAIF Nuclear Symposium. Marshall Space Flight Center.

- ↑ "U.S. Space Objects Registry".

- ↑ "Conventional Disposal Method: Rockets and Graveyard Orbits". Tethers.

- ↑ "FCC Enters Orbital Debris Debate". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2009-07-24.

- ↑ "Object SL-8 R/B - 29659U - 06060B". Forecast for Space Junk Reentry. Satview. 11 March 2014.

- ↑ The video tape of a partial launch attempt which was retrieved by UN weapons inspectors later surfaced showing that the rocket prematurely exploded 45 seconds after its launch.[28][29][30]

- ↑ "UNMOVIC report" (PDF). United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission. p. 434 ff.

- ↑ "Deception Activities - Iraq Special Weapons". FAS. Archived from the original on 22 April 1999.

- ↑ "Al-Abid LV".

- 1 2 Malik, Tariq (28 September 2008). "SpaceX Successfully Launches Falcon 1 Rocket Into Orbit". Space.com.

- ↑ "First time in History". The Satellite Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ↑ "SATCAT Boxscore". celestrak.com. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ The first satellite built by Argentina, Arsat 1, was launched later in 2014

- ↑ The first satellite built by Singapore, X-Sat, was launched aboard a PSLV rocket later on 20 April 2011

- ↑ T.S., Subramanian (20 April 2011). "PSLV-C16 puts 3 satellites in orbit". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ↑ Esiafi 1 (former private American Comstar D4) satellite was transferred to Tonga being at orbit after launch in 1981

- ↑ "India launches Switzerland's first satellite". Swiss Info. 23 September 2009.

- ↑ In a difference of first full Bulgarian Intercosmos Bulgaria 1300 satellite, Poland's near first satellite, Intercosmos Copernicus 500 in 1973, were constructed and owned in cooperation with Soviet Union under the same Interkosmos program.

- ↑ "First Romanian satellite Goliat successfully launched".

- ↑ "BKA (BelKa 2)". skyrocket.de.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan`s first telecommunications satellite launched to orbit". APA.

- ↑ Austria's first two satellites, TUGSAT-1 and UniBRITE, were launched together aboard the same carrier rocket in 2013. Both were based on the Canadian Generic Nanosatellite Bus design, however TUGSAT was assembled by Austrian engineers at Graz University of Technology while UniBRITE was built by the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies for the University of Vienna.

- ↑ "Nanosatellite Launch Service". University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Bermudasat 1 (former private American EchoStar VI) satellite was transferred to Bermuda being at orbit after launch in 2000

- ↑ "PUCP-SAT-1 Deploys POCKET-PUCP Femtosatellite". AMSAT-UK. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Italian built (by La Sapienza) first Iraqi small experimental Earth observation cubesat-satellite Tigrisat Iraq to launch its first satellite before the end of 2013 launched in 2014 Iraq launches its first satellite – TigriSat prior to ordered abroad also for $50 million the first national large communication satellite near 2015.Iraq launching the first satellite into space at a cost of $ 50 millionIraqi first satellite into space in 2015 Archived 15 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ghana launches its first satellite into space". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Burleson, Daphne (2005). Space Programs Outside the United States. McFarland & Company. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7864-1852-7.

- ↑ Gruntman, Mike (2004). Blazing the Trail. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 426. ISBN 978-1-56347-705-8.

- ↑ Harvey, Brian (2003). Europe's Space Programme. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-85233-722-3.

- ↑ Day, Dwayne A. (9 May 2011). "Iraqi bird: Beyond Saddam's space program". The Space Review.

- ↑ "Iraq: Whether it is legal to purchase and own satellite dishes in Iraq, and the sanction for owning satellite dishes if it is illegal". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea says it successfully launched controversial satellite into orbit". MSNBC. 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Wissam Said Idrissi. "Libsat - Libyan Satellite Project". libsat.ly.

- ↑ Graham-Harrison, Emma (9 April 2012). "Afghanistan announces satellite tender". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Afghanistan deploys its first satellite into orbit by February". khaama.com.

- ↑ "Angola to launch its first satellite in Nov 2016". NexTV Africa Middle East.

- ↑ "Satellite department to be set up in Armenia’s national telecommunication center". arka.am.

- ↑ "Canada’s MDA Ready to Help Armenia Launch First Comsat". Asbarez News.

- ↑ "Armenia to Launch Its First Satellite". sputniknews.com. 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "China keen on Armenian satellite launch project". arka.am.

- ↑ Rahman, Sajjadur (27 November 2009). "Bangladesh plans to launch satellite". The Daily Star.

- ↑ "Royal Group receives right to launch first Cambodia satellite". 19 April 2011.

- ↑ "China to launch second African satellite-Science-Tech-chinadaily.com.cn". chinadaily.com.cn.

- ↑ "Vremenik". Astronautica.

- ↑ "ESSS". ethiosss.org.et. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ethiopia to design and construct first Satellite". ethioabay.com.

- ↑ Kasia Augustyniak. "Space Technology and Science Group Oy - Finland (STSG Oy) to design, develop and launch first Ethiopian research satellite - ETHOSAT1". spacetsg.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ghana to launch first satellite in 2020". BiztechAfrica.

- ↑ Bray, Allison (1 December 2012). "Students hope to launch first ever Irish satellite". The Independent. Ireland.

- ↑ "Behance". Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Meet the PocketQube team: Sunewnewsat". PocketQube Shop.

- ↑ Team Interview Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Curriculum vitae - University of Nairobi

- ↑ "SLatvijas pirmais satelīts "Venta-1"". VATP. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑

- ↑ "Наши публикации". ComelPro.

- ↑ "Mongolia to Launch its First Satellite". Mongolia Economy. 13 May 2012.

- ↑ "Burma to launch first state-owned satellite, expand communications". News. Mizzima. 14 June 2011. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "A step for Nepal own Satellite". Nabin Chaudhary.

- ↑ 张军棉. "Nepal: No satellite launching plan so far". china.org.cn.

- ↑ Ananth Krishnan. "Nepal may turn to China for satellite plan". The Hindu. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Bathgate, Adrian (19 December 2005). "NZ Satellite Closer After Approval Given to Use Dedicated Orbital Slot". Red Orbit. Archived from the original on 29 February 2008.

"NZ's first satellite gets go-ahead to fly". NZ Herald. 17 December 2005. - ↑ "KiwiSat joins space race". NZ Herald. 18 January 2003.

- ↑ "NZ set to join the space age". Stuff Magazine. New Zealand. 9 October 2009.

- ↑ "New Zealand Rocket developments". Rocketlab. Archived from the original on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Nicaragua says Nicasat-1 satellite still set for 2016 launch". telecompaper.com.

- ↑ Zachary Volkert. "Paraguay to vote on aerospace agency bill in 2014". BNamericas. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- ↑ "Why a little country like Paraguay is launching a space program". GlobalPost.

- ↑ "SOSA". Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- ↑ "skCUBE - prvá slovenská družica » English". Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ "SATTELITE skCUBE". Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- ↑

- ↑ "NEMO-HD - UTIAS Space Flight Laboratory". utias-sfl.net.

- ↑ "Slovenia will soon get its first satellite". rtvslo.si.

- ↑ "SSTL Contracted to Establish Sri Lanka Space Agency". Satellite Today. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ "SSTL contracted to establish Sri Lanka Space Agency". Adaderana. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ "Syria On The Internet -". souria.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

- ↑ "Design and prototype of a flight microstrip antennas for the Pico satellite ERPSat-1". Explore. IEEE.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan Planning First Satellite". Sat News. 18 May 2001. Archived from the original on 2001-07-13.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan Planning to Launch Two Satellites With Russian Help". Red Orbit. 8 June 2004. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Morrill, Dan. "Hack a Satellite while it is in orbit". ITtoolbox. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ "AsiaSat accuses Falungong of hacking satellite signals". Press Trust of India. 22 November 2004.

- 1 2 Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (18 January 2007). "China Tests Anti-Satellite Weapon, Unnerving U.S.". New York Times.

- ↑ "Navy Missile Successful as Spy Satellite Is Shot Down". Popular Mechanics. 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Singer, Jeremy (2003). "U.S.-Led Forces Destroy GPS Jamming Systems in Iraq". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Brewin, Bob (2003). "Homemade GPS jammers raise concerns". Computerworld. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ "Iran government jamming exile satellite TV". Iran Focus. 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Selding, Peter de (2007). "Libya Pinpointed as Source of Months-Long Satellite Jamming in 2006". Space.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Satellite |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Satellites. |

- Satellite at DMOZ

- Satellite Ground Tracks Real time satellite tracks (Full catalog of satellite orbit). (in English) (in German) (in Spanish) (in French) (in Italian) (in Portuguese) (in Chinese)

- Real Time Satellite Tracking provides real-time tracks for about 17000 satellites, as well as 5-day predictions of visibility

- Heavens Above provides 10-day predictions of satellite visibility

- Satflare tracks in real time all the satellites orbiting the Earth

- 'Eyes in the Sky' Free video by the Vega Science Trust and the BBC/OU Satellites and their implications over the last 50 years.