Durham, North Carolina

| Durham, North Carolina | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

Clockwise from top: Durham skyline, North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, Five Points, Carolina Theater, Durham Performing Arts Center, Duke Chapel | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Bull City; City of Medicine[1] | ||

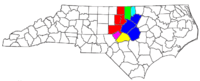

Location in Durham County and the state of North Carolina. | ||

Durham, North Carolina Location in the contiguous United States | ||

| Coordinates: 35°59′19″N 78°54′26″W / 35.98861°N 78.90722°WCoordinates: 35°59′19″N 78°54′26″W / 35.98861°N 78.90722°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | North Carolina | |

| County | Durham | |

| Incorporated | April 10, 1869[2] | |

| Named for | Bartlett S. Durham | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Council-Manager | |

| • Mayor | Bill Bell | |

| • City Manager | Tom Bonfield | |

| • Deputy City Managers | W. Bowman "Bo" Ferguson, Wanda Page, Keith Chadwell | |

| • City Council Members | Cora Cole-McFadden, Eddie Davis, Jillian Johnson, Don Moffitt, Charlie Reece, Steve Schewel | |

| Area | ||

| • City | 108.3 sq mi (280.4 km2) | |

| • Land | 107.4 sq mi (278.1 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.9 sq mi (2.4 km2) | |

| Elevation | 404 ft (123 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • City | 228,330 | |

| • Estimate (2016)[3] | 263,016 | |

| • Density | 2,100/sq mi (810/km2) | |

| • Metro | 542,710 (US: 100th) | |

| • CSA | 2,037,430 | |

| Demonym(s) | Durhamite | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP codes | 27701, 27702, 27703, 27704, 27705, 27706, 27707, 27708, 27709, 27710, 27711, 27712, 27713, 27715, 27717, 27722 | |

| Area code(s) | 919 | |

| FIPS code | 37-19000[4] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1020059[5] | |

| Website |

durhamnc | |

Durham is a city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the county seat of Durham County.[6] The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the city's population to be 251,893 as of July 1, 2014.[7] Durham is the core of the four-county Durham-Chapel Hill Metropolitan Area, which has a population of 542,710 as of U.S. Census 2014 Population Estimates. The US Office of Management and Budget also includes Durham as a part of the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill Combined Statistical Area, which has a population of 2,037,430 as of U.S. Census 2014 Population Estimates.[8]

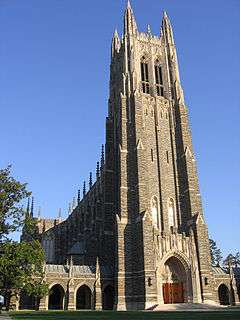

It is the home of Duke University and North Carolina Central University, and is also one of the vertices of the Research Triangle area (home of the Research Triangle Park).[9]

History

Pre-establishment

The Eno and the Occoneechi, related to the Sioux and the Shakori, lived and farmed in the area which became Durham. They may have established a village named Adshusheer on the site. The Great Indian Trading Path has been traced through Durham, and Native Americans helped to mold the area by establishing settlements and commercial transportation routes.

In 1701, Durham's beauty was chronicled by the English explorer John Lawson, who called the area "the flower of the Carolinas." During the mid-1700s, Scots, Irish, and English colonists settled on land granted to George Carteret by King Charles I (for whom the Carolinas are named). Early settlers built gristmills, such as West Point, and worked the land.

Prior to the American Revolution, frontiersmen in what is now Durham were involved in the Regulator movement. According to legend, Loyalist militia cut Cornwallis Road through this area in 1771 to quell the rebellion. Later, William Johnston, a local shopkeeper and farmer, made Revolutionaries' munitions, served in the Provincial Capital Congress in 1775, and helped underwrite Daniel Boone's westward explorations.

Large plantations, Hardscrabble, Cameron, and Leigh among them, were established in the antebellum period. By 1860, Stagville Plantation lay at the center of one of the largest plantation holdings in the South. African slaves were brought to labor on these farms and plantations, and slave quarters became the hearth of distinctively Southern cultural traditions involving crafts, social relations, life rituals, music, and dance. There were free African-Americans in the area as well, including several who fought in the Revolutionary War.

Antebellum and Civil War

Prior to the arrival of the railroad, the area now known as Durham was the eastern part of present-day Orange County and was almost entirely agricultural, with a few businesses catering to travelers (particularly livestock drivers) along the Hillsborough Road. This road, eventually followed by US Route 70, was the major east-west route in North Carolina from colonial times until the construction of interstate highways. Steady population growth and an intersection with the road connecting Roxboro and Fayetteville made the area near this site suitable for a US Post Office, which was established in 1827. (Roxboro, Fayetteville and Hillsborough Roads remain major thoroughfares in Durham, although they no longer exactly follow their early 19th century rights-of-way.)

Durham's location is a result of the needs of the 19th century railroad industry. The wood-burning steam locomotives of the time had to stop frequently for wood and water and the new North Carolina Railroad needed a depot between the settled towns of Raleigh and Hillsborough. The residents of what is now downtown Durham thought their businesses catering to livestock drivers had a better future than a new-fangled nonsense like a railroad and refused to sell or lease land for a depot. Eventually a railway depot was established on land donated by Bartlett S. Durham in 1849.[10]

Durham Station, as it was known for its first 20 years, was just another depot for the occasional passenger or express package until early April 1865 when the Federal Army commanded by Major General William T. Sherman occupied the nearby state capital of Raleigh during the American Civil War. The last formidable Confederate Army in the South, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, was headquartered in Greensboro 50 miles (80 km) to the west. After the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia by Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, Virginia on April 9, 1865, Gen. Johnston sought surrender terms, which were negotiated on April 17, 18 and 26 at Bennett Place, the small farm of James and Nancy Bennett, located halfway between the army's lines about 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Durham Station. While these negotiations prevented a battle in Durham, the wholesale looting of homes and businesses by Union cavalry caused a long-standing bitterness in the region towards the federal government and the Republican Party.

Fortunately for Durham, its future had nothing to do with 19th-century politics. As both armies passed through Durham, Hillsborough, and surrounding Piedmont communities, they confiscated the area's Brightleaf Tobacco, which had a milder flavor than other tobacco varieties. Durham's tobacco was far more pleasant to smoke or chew than any tobacco they had ever had and when they returned home and couldn't get anything like it, they started sending letters to Durham to get more.

Reconstruction and the rise of Durham tobacco

The community of Durham Station grew slowly before the Civil War, but expanded rapidly following the war. Much of this growth attributed to the establishment of a thriving tobacco industry. Veterans returned home after the war, with an interest in acquiring more of the great tobacco they had sampled in North Carolina. Numerous orders were mailed to John Ruffin Green's tobacco company requesting more of the Durham tobacco. W.T. Blackwell partnered with Green and renamed the company as the "Bull Durham Tobacco Factory". The name "Bull Durham" is said to have been taken from the bull on the British Colman's Mustard, which Mr. Blackwell (mistakenly) believed was manufactured in Durham, England. Mustard, known as Durham Mustard, was originally produced in Durham, England, by Mrs Clements and later by Ainsley during the eighteenth century. However, production of the original Durham Mustard has now been passed into the hands of Colman's of Norwich, England.

Incorporation

As Durham Station's population rapidly increased, the station became a town and was incorporated by act of the North Carolina General Assembly, on April 10, 1869. It was named for the man who provided the land on which the station was built, Dr. Bartlett Durham. At the time of its incorporation by the General Assembly, Durham was located in Orange County. The increase in business activity, land transfers etc., made the day long trip back and forth to the county seat in Hillsborough untenable, so twelve years later, on April 17, 1881, a bill for the establishment of Durham County was ratified by the General Assembly, having been introduced by Caleb B.Green, creating Durham County from the eastern portion of Orange County and the western portion of Wake County. In 1911, parts of Cedar Fork Township of Wake County was transferred to Durham County and became Carr Township.[2]

Early growth (1900–1970)

The rapid growth and prosperity of the Bull Durham Tobacco Company, and Washington Duke's W. Duke & Sons Tobacco Company, resulted in the rapid growth of the city of Durham. Washington Duke was a good businessman, but his sons were brilliant and established what amounted to a monopoly of the smoking and chewing tobacco business in the United States by 1900. In the early 1910s, the Federal Government forced a breakup of the Duke's business under the antitrust laws. The Dukes retained what became known as American Tobacco, a major corporation in its own right, with manufacturing based in Durham. American Tobacco's ubiquitous advertisements on radio shows beginning in the 1930s and television shows up to 1970 was the nation's image of Durham until Duke University supplanted it in the late 20th century.

Prevented from further investment in the tobacco industry, the Dukes turned to the then new industry of electric power generation, which they had been investing in since the early 1890s. Duke Power (now Duke Energy) brought in electricity from hydroelectric dams in the western mountains of North Carolina through the newly invented technology of high voltage power lines. At this time (1910–1920), the few towns and cities in North Carolina that had electricity depended on local "powerhouses". These were large, noisy, and smoky coal-fired plants located next to the railroad tracks. Duke Power quickly took over the electricity franchises in these towns and then electrified all the other towns of central and western North Carolina, making even more money than they ever made from tobacco. Duke Power also had a significant business in local franchises for public transit (buses and trolleys) before local government took over this responsibility in the mid- to late 20th century. Duke Power ran Durham's public bus system (now the Durham Area Transit Authority) until 1991.

The success of the tobacco industry in the late 19th and early 20th century encouraged the then-growing textile industry to locate just outside Durham. The early electrification of Durham was also a large incentive. Drawing a labor force from the economic demise of single family farms in the region at the time, these textile mills doubled the population of Durham. These areas were known as East Durham and West Durham until they were eventually annexed by the City of Durham.

Much of the early city architecture, both commercial and residential, dates from the period of 1890–1930. Durham recorded its worst fire in history on March 23, 1914. The multimillion-dollar blaze destroyed a large portion of the downtown business district. The fire department's water source failed during the blaze, prompting voters to establish a city-owned water system in place of the private systems that had served the city since 1887.[11]

Durham quickly developed a vibrant Black community, the center of which was an area known as Hayti, (pronounced HAY-tie), just south of the center of town, where some of the most prominent and successful black-owned businesses in the country during the early 20th century were established. These businesses — the best known of which are North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and Mechanics & Farmers Bank — were centered on Parrish St., which would come to be known as "Black Wall Street." In 1910, Dr. James E. Shepard founded North Carolina Central University, the nation's first publicly supported liberal arts college for African-Americans.

In 1924, James Buchanan Duke established a philanthropic foundation in honor of his father Washington Duke to support Trinity College in Durham. The college changed its name to Duke University and built a large campus and hospital a mile west of Trinity College (the original site of Trinity College is now known as the Duke East Campus).

Durham's manufacturing fortunes declined during the mid-20th century. Textile mills began to close during the 1930s. Competition from other tobacco companies (as well as a decrease in smoking after the 1960s) reduced revenues from Durham's tobacco industry.

In a far-sighted move in the late 1950s, Duke University, along with the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University in Raleigh, persuaded the North Carolina Legislature to purchase a large tract of sparsely settled land in southern Durham County and create the nation's first "science park" for industry. Cheap land and a steady supply of trained workers from the local universities made the Research Triangle Park an enormous success which, along with the expansion resulting from the clinical and scientific advances of Duke Medical Center and Duke University, more than made up for the decline of Durham's tobacco and textile industries.

Civil Rights Movement

As a result of its substantial African-American community, a prominent civil rights movement developed in Durham. Multiple sit-ins were held, and Martin Luther King, Jr., visited the city during the struggle for equal rights. The Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, organized in 1935 by C.C. Spaulding and James E. Shepard, has been cited nationally for its role in the sit-in movements of the 1950s–60s. The committee also has used its voting strength to pursue social and economic rights for African-Americans and other ethnic groups. In the late 1950s, Douglas E. Moore, minister of Durham's Asbury Temple Methodist Church, along with other religious and community leaders, pioneered sit-ins throughout North Carolina to protest discrimination at lunch counters that served only whites.

Widely credited as the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, on June 23, 1957, Moore and six others assembled at the church to plan the protest. The young African Americans moved over to the segregated Royal Ice Cream Parlor and took up whites-only booths. When they refused to budge, the manager called the police who charged them with trespassing. Unlike the Greensboro Four, three years later, the Royal Seven were arrested and ultimately found guilty of trespassing.[13][14][15]

The six-month-long sit-in at a Woolworth's counter in Greensboro, NC, captured the nation's attention. Within days, Martin Luther King Jr. met Moore in Durham, where King coined his famous rallying cry "Fill up the jails," during a speech at White Rock Baptist Church. Advocating non-violent confrontation with segregation laws for the first time, King said, "Let us not fear going to jail. If the officials threaten to arrest us for standing up for our rights, we must answer by saying that we are willing and prepared to fill up the jails of the South."

This community was not enough to prevent the demolition of portions of the Hayti district for the construction of the Durham Freeway during the late 1960s.[16]The freeway construction resulted in losses to other historic neighborhoods, including Morehead Hills, West End, and West Durham. Combined with large-scale demolition using Urban Renewal funds, Durham suffered significant losses to its historic architectural base.

1970s – present

In 1970, the Census Bureau reported city's population as 38.8% black and 60.8% white.[17] Durham's growth began to rekindle during the 1970s and 1980s, with the construction of multiple housing developments in the southern part of the city, nearest Research Triangle Park, and the beginnings of downtown revitalization. In 1975, the St. Joseph's Historical Foundation at the Hayti Heritage Center was incorporated to "preserve the heritage of the old Hayti community, and to promote the understanding of and appreciation for the African American experience and African Americans' contributions to world culture."[18] A new downtown baseball stadium was constructed for the Durham Bulls in 1994. The Durham Performing Arts Center now ranks in the top ten in theater ticket sales in the US according to Pollstar magazine. Many famous people have performed there including B.B. King and Willie Nelson. After the departure of the tobacco industry, large-scale renovations of the historic factories into offices, condominiums, and restaurants began to reshape downtown.[19] While these efforts continue, the large majority of Durham's residential and retail growth since 1990 has been along the I-40 corridor in southern Durham County.

Major employers in Durham are Duke University and Duke Medical Center (39,000 employees, 14,000 students), about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the original downtown area, and companies in the Research Triangle Park (49,000 employees), about 10 miles (16 km) southeast. These centers are connected by the Durham Freeway (NC 147).

Downtown revitalization

In recent years the city of Durham has stepped up revitalization of its downtown and undergone an economic and cultural renaissance of sorts. Partnering with developers from around the world, the city continues to promote the redevelopment of many of its former tobacco districts, projects supplemented by the earlier construction of the Durham Performing Arts Center and new Durham Bulls Athletic Park[20] The American Tobacco Historic District, adjacent to both the athletic park and performing arts center, is one such project, having successfully lured a number of restaurants, entertainment venues, and office space geared toward hi-tech entrepreneurs, investors, and startups[21] The American Underground section of the American Tobacco Campus, home to a number of successful small software firms including Red Hat, was recently selected by Google to host its launch of the Google Glass Road show in October 2013[22] The district is also slated for expansion featuring 158,000 square feet of offices, retail, residential or hotel space[23] The Durham County Justice Center, a major addition to downtown Durham, was completed in early 2013.

Additionally, many of the historic tobacco buildings elsewhere in the city have been converted into loft-style apartment complexes. The downtown corridor along West Main St. has seen significant redevelopment including a number of bars, entertainment venues, art studios[24] and co-working spaces[25] in addition to shopping and dining in nearby Brightleaf Square, another former tobacco warehouse in the Bright Leaf Historic District. Other current and future projects include expansion of the open-space surrounding the American Tobacco Trail, a number of new hotels and apartment complexes, a $6.35-million facelift of Durham City Hall, and ongoing redevelopment of the Duke University Central Campus.

In 2013, 21c Museum Hotels announced plans to fully renovate the Hill Building. The renovations will add a contemporary art museum and upscale restaurant to the historic building. Additionally, a boutique hotel will also be built in this major renovation effort in downtown Durham. Skansa Construction is responsible for managing this project.[26]

In 2014, it was announced that downtown Durham would be the site of a brand new 26 story high building, tentatively named "City Center Tower". Construction has already started, and the building will be at the corner of Main St and Corcoran St. It will be directly across from Durham's current tallest building, but once completed, will be the new tallest building in downtown Durham and the 4th largest building in the Triangle. Originally scheduled for a 2016 opening, the building now is expected to open in May 2018.[27] This is an ambitious, $80 million project.[28]

Geography

Durham is located in the east-central part of the Piedmont region at 35°59′19″N 78°54′26″W / 35.98861°N 78.90722°W (35.988644, −78.907167).[29] Like much of the region, its topography is generally flat with some rolling hills.

The city has a total area of 108.3 square miles (280.4 km2), of which 107.4 square miles (278.1 km2) is land and 0.93 square miles (2.4 km2), or 0.84%, is water.[30]

The soil is predominantly clay, making it poor for agriculture. The Eno River, a tributary of the Neuse River, passes through the northern part of Durham, along with several other small creeks. The center of Durham is on a ridge that forms the divide between the Neuse River watershed, flowing east to Pamlico Sound, and the Cape Fear River watershed, flowing south to the Atlantic near Wilmington.

Cityscape

Climate

Durham is classified as a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) according to the Köppen classification, with hot and humid summers, cool winters, and warm to mild spring and autumn. Durham receives abundant precipitation, with thunderstorms common in the summer and temperatures from 80 to 100 degrees F. The region sees an average of 6.8 inches (170 mm) of snow per year, which usually melts within a few days.

| Climate data for Durham, North Carolina | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

84 (29) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

81 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 49.2 (9.6) |

53.4 (11.9) |

62.1 (16.7) |

71.3 (21.8) |

78.6 (25.9) |

85.0 (29.4) |

88.6 (31.4) |

86.8 (30.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

62.0 (16.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

70.18 (21.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27.8 (−2.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

37.0 (2.8) |

45.8 (7.7) |

55.6 (13.1) |

65.4 (18.6) |

70.1 (21.2) |

67.9 (19.9) |

60.3 (15.7) |

46.6 (8.1) |

37.4 (3) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

47.82 (8.79) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−2 (−19) |

11 (−12) |

23 (−5) |

29 (−2) |

38 (3) |

48 (9) |

46 (8) |

37 (3) |

19 (−7) |

11 (−12) |

0 (−18) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.44 (112.8) |

3.70 (94) |

4.68 (118.9) |

3.41 (86.6) |

4.59 (116.6) |

4.01 (101.9) |

3.95 (100.3) |

4.38 (111.3) |

4.36 (110.7) |

3.71 (94.2) |

3.38 (85.9) |

3.43 (87.1) |

48.04 (1,220.2) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.8 (4.6) |

2.6 (6.6) |

1.7 (4.3) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

.1 (0.3) |

.6 (1.5) |

6.8 (17.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.2 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 8.9 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 111.7 |

| Average snowy days | .7 | .8 | .5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .1 | .2 | 2.3 |

| Source #1: NOAA[31] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: The Weather Channel (extreme temps)[32] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 2,041 | — | |

| 1890 | 5,485 | 168.7% | |

| 1900 | 6,679 | 21.8% | |

| 1910 | 18,241 | 173.1% | |

| 1920 | 21,719 | 19.1% | |

| 1930 | 52,037 | 139.6% | |

| 1940 | 60,195 | 15.7% | |

| 1950 | 71,311 | 18.5% | |

| 1960 | 78,302 | 9.8% | |

| 1970 | 95,438 | 21.9% | |

| 1980 | 101,149 | 6.0% | |

| 1990 | 136,611 | 35.1% | |

| 2000 | 187,035 | 36.9% | |

| 2010 | 228,330 | 22.1% | |

| Est. 2016 | 263,016 | [3] | 15.2% |

As of the 2010 census,[4] there were 228,330 people, 93,441 households, and 52,409 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,406.0 people per square mile (928.9/km²). There were 103,221 housing units at an average density of 1,087.7 per square mile (419.9/km²). The racial composition of the city was: 42.45% White, 40.96% Black or African American, 5.07% Asian American, 0.51% Native American, 0.07% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 8.28% some other race, and 2.66% two or more races; 14.22% were Hispanic or Latino of any race. Non-Hispanic White comprised 37.9% of the population.

Durham's population, as of July 1, 2014 and according to the 2014 US census data estimate, has grown to 251,893[34] making it the 46th fastest growing city in the US, and the 2nd fastest growing city in North Carolina behind Cary but ahead of Charlotte, Raleigh and Greensboro.[34]

There were 93,441 households out of which 27.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.2% were married couples living together, 15.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.9% were non-families. 33.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.34, and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city, the population was spread out with 22.7% under the age of 18, 14.1% from 18 to 24, 33.6% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 8.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.1 years. For every 100 females there were 92.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $47,394, and the median income for a family was $60,157. Males had a median income of $35,202 versus $30,359 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,156. About 13.1% of families and 18.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.3% of those under age 18 and 10.1% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Duke University and Duke University Health System are Durham's largest employers. Below is a list of Durham's largest employers.[35]

| Employer | No. of employees |

|---|---|

| Duke University & Duke Univ. Health System | 34,863 |

| IBM | 10,000 |

| Durham Public Schools | 4,600 |

| GlaxoSmithKline | 3,700 |

| Blue Cross & Blue Shield of NC | 3,200 |

| City of Durham | 2,437 |

| Fidelity Investments | 2,400 |

| Quintiles | 2,400 |

| RTI International | 2,300 |

| Durham VA Medical Center | 2,162 |

| Cree | 2,125 |

| AW North Carolina | 2,000 |

Culture

Durham is the venue for the annual Bull Durham Blues Festival.[36] Other events include jazz festivals, plays, symphony concerts, art exhibitions, and a multitude of cultural expositions, including the American Dance Festival and the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival. A center of Durham's culture is its Carolina Theatre, which presents concerts, comedy and arts in historic Fletcher Hall and Independent and repertory film in its cinemas. Notable dining establishments are primarily concentrated in the Ninth Street, Brightleaf, and University Drive areas. There is a resurgence of restaurants in and around the downtown area, including several new restaurants in the American Tobacco District. The Nasher Museum of Art opened in October 2005 and has produced nationally recognized traveling exhibitions of global, contemporary art.

The Durham Association for Downtown Arts (DADA) is a non-profit arts organization located in the downtown area. It was founded in 1998 and then incorporated in 2000. The organization's mission is a commitment to the development, presentation and fiscal sponsorship of original art and performance in Durham. DADA strives to support local artists working in a diversity of artistic media. Emphasizing community, DADA helps local residents gain access to these artists by providing free or low-cost venue admission.

Music

Durham has an active and diverse local music culture. Artists' styles range from jazz, hip-hop, soul, folk, americana, blues, bluegrass, punk, metal and rock. Popular bands and musicians include Branford Marsalis, Iron & Wine, Carolina Chocolate Drops, The Mountain Goats, John Dee Holeman, 9th Wonder, Red Clay Ramblers, The Old Ceremony, Megafaun, Curtis Eller, Mount Moriah, Hiss Golden Messenger, Sylvan Esso, Hammer No More the Fingers, and Yahzarah, as well as Jim Mills, banjo player and Gibson Pre-War banjo expert. Additionally, members of The Butchies, Superchunk, Chatham County Line, and the Avett Brothers live in Durham.

Merge Records, a successful independent record label, has its headquarters in downtown Durham.[37] Other independent record labels include Jamla, 307 Knox, Churchkey Records, and Paradise of Bachelors. Roots label Sugar Hill Records was founded in Durham, by Barry Lyle Poss,[38] before it moved to Nashville in 1998. In 1996, the feminist / queer record label Mr. Lady Records was founded and operated in Durham until its demise in 2004.[39]

Duke University's radio station WXDU is an active participant in the community.

Durham has a rich history of African American rhythm and blues, soul, and funk music. In the 1960s and 1970s, more than 40 R&B, soul, and funk groups—including The Modulations, The Black Experience Band, The Communicators, and Duralcha—recorded over 30 singles and three full-length albums. Durham was also home to ten recording labels that released soul music, though most of them only released one or two records apiece. A few successful local soul groups from Durham also recorded on national labels like United Artists or on regional labels in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast.[40]

Visual arts

Durham is home to the nationally known Scrap Exchange, the largest nonprofit creative reuse arts center in the country, and the Nasher Museum of Art as well as a plethora of smaller visual arts galleries and studios. As a testament to the arts, downtown Durham sponsors an organically grown celebration of culture and arts on display every third Friday of the month, year round. The event is named and has come to be known as 3rd Friday.

A selection of locally renowned galleries remain in business throughout the city. Galleries include but are not limited to local spots such as the Pleiades Gallery, The Carrack Modern Art, and Golden Belt Studios. Supporting a variety of local, nationwide, and worldwide talent, these galleries often host weekly events and art shows. The Durham Art Walk is another annual arts festival hosted in May each year in downtown Durham. The Durham Art Walk features a variety of artists that come together each year for a large showcase of work in the streets of Durham. A secondary magnet school, Durham School of the Arts, is also located in downtown Durham. Durham School of the Arts focuses on providing students with an education in various forms of art ranging from visual to the performing arts.[41]

Sports

Collegiate athletics are a primary focus in Durham. Duke University's men's basketball team draws a large following, selling out every home game at Cameron Indoor Stadium in 2009.[42] The fans are known as the Cameron Crazies and are known nationwide for their chants and rowdiness. The team has won the NCAA Division I championship three times since 2001 and five times overall.[43] Duke competes in a total of 26 sports in the Atlantic Coast Conference.

Durham's professional sports team is the Durham Bulls International League baseball team. A movie involving an earlier Carolina League team of that name, Bull Durham, was produced in 1988. Today's Bulls play in the Durham Bulls Athletic Park, on the southern end of downtown, constructed in 1994. Now with one of the newest stadiums in the minor leagues, the Bulls usually generate an annual attendance of around 500,000. Previously the Durham Athletic Park, located on the northern end of downtown, had served as the Bull's homebase. Historically, many players for the current and former Durham Bulls teams have transferred to the big leagues after several years in the minor leagues. The DAP has been preserved for the use of other teams as well as for concerts sponsored by the City of Durham and other events. The Durham Dragons, a women's fast pitch softball team, played in the Durham Athletic Park from 1998–2000. The DAP recently went through a $5 million renovation.

Politics

The area is predominantly Democratic, and has voted for the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in every election since the city's founding in 1869. Durham is an activist community and politics are lively, visible, and often contentious, and like many communities, often dealing with issues of race and class. The shifting alliances of the area's political action committees since the 1980s has led to a very active local political scene. Notable groups include the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, the Durham People's Alliance, and the Friends of Durham. The first two groups tend to be affiliated with Democratic party activists, while the third group tends to attract Republican activists. Compared to other similarly sized Southern cities, Durham has a larger than average population of middle class African-Americans and white liberals. Working together in coalition, these two groups have dominated city and county politics since the early 1980s.

Durham operates under a council-manager government. The mayor, since 2001, is Bill Bell, who was most recently reelected in 2011 with 82% of the vote in a runoff election.[44] The seven-member City Council is the primary budgetary and lawmaking authority.[45]

Key political issues have been the redevelopment of Downtown Durham and revival of other historic neighborhoods and commercial districts, the fluoridation of public drinking water, a 45% reduction of crime, a 10-year plan to end homelessness, initiatives to reduce truancy, issues related to growth and development. Naturally, a merger of Durham City Schools (several inner city neighborhoods) and Durham County Schools in the early 1990s has not been without controversy.

Federally, Durham is split between North Carolina's 4th congressional district, North Carolina's 1st congressional district and North Carolina's 6th congressional district following redistricting after the 2010 Census. The 4th district is represented by Democrat David Price, elected in 1996. The 1st district is represented by Democrat G.K. Butterfield, elected in 2004. The 6th district is represented by Republican Mark Walker, elected in 2014.

Since 2003 the city has had a policy to prohibit police from inquiring into the citizenship status of persons unless they have otherwise been arrested or charged with a crime. A city council resolution mandates that police officers "...may not request specific documents for the sole purpose of determining a person's civil immigration status, and may not initiate police action based solely on a person's civil immigration status ..."[46] Since 2010, the Durham police have accepted the Mexican Consular Identification Card as a valid form of identification.[47]

In 2006, racial and community tensions stirred[48] following false allegations of a sexual assault by three white members of the Duke University lacrosse team in what is now known as the 2006 Duke University lacrosse case. The allegations were made by Crystal Gail Mangum a young African- American woman, student, stripper and mother of two young children. She and another young woman had been hired to dance at a party that the team held in an off-campus house. In 2007, all charges in the case were dropped and the players were declared innocent. Durham County District Attorney Mike Nifong was dismissed from his job and disbarred from legal practice for his criminal misconduct handling of the case including withholding of exculpatory evidence. There have been several other results from the case, including lawsuits against both city and Duke University officials.

The new Durham County Justice Center was completed in early 2013.

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools in Durham are run by Durham Public Schools, the eighth largest school district in North Carolina. The district runs 46 public schools, consisting of 30 elementary, 10 middle, 2 secondary, and 12 high schools. Several magnet high schools focus on distinct subject areas, such as the Durham School of the Arts and the City of Medicine Academy.[49] Public schools in Durham were partially segregated until 1970.

The North Carolina School for Science and Mathematics is a high school operated by the University of North Carolina in central Durham. The residential school accepts rising juniors living in North Carolina with a focus on science, mathematics, and technology.

There are several charter school options as well including Research Triangle High School (a STEM school in Research Triangle Park), Voyager Academy (K-12), Kestrel Heights School (K-12) and Maureen Joy Charter School (K-8).

Several private schools also operate in Durham,[50] such as Durham Academy, Carolina Friends School, and the Duke School. There are also a number of religious schools including Trinity School of Durham and Chapel Hill.

In December 2007, Forbes.com ranked Durham as one of the "Top 20 Places to Educate Your Child;" Durham was the only MSA from North Carolina to make the list.[51][52]

Colleges and universities

Duke University has approximately 14,000 students split evenly between graduates and undergraduates.[53] Duke's 8600 acre campus and Medical Center are located in western Durham, about 2 miles (3.2 km) from downtown. Duke forms one of the three vertices of the Research Triangle along with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University. The university's research, medical, and teaching efforts are all among the highest-ranked in both the United States and the world.

North Carolina Central University is a public, historically black university located in southeastern Durham. NCCU was ranked the number 1 Public HBCU in the nation by U.S. News & World Report 2010 and 2011. It was ranked the 10th best HBCU overall. The university was founded in 1910 to address the needs of the region's black population, and now grants baccalaureate, master's, professional and doctoral degrees. NCCU became a public University when it joined the University of North Carolina system in 1972.

Durham Technical Community College is a two-year public institution that grants associate degrees.

Media

The major daily newspaper in Durham is The Herald-Sun, which began publication in 1893. The Durham-based Independent Weekly, noted for its progressive/liberal perspective, provides political and entertainment news for the greater Research Triangle; it began publication in 1983.

Durham is part of the Raleigh-Durham-Fayetteville Designated Market Area, the 24th largest broadcast television market in the United States. ABC owned and operated WTVD is licensed to and based in Durham, while the studios for statewide public television service UNC-TV are based in Research Triangle Park. All major U.S. television networks have affiliates serving the region.

The city is part of the Raleigh-Durham Arbitron radio market, ranked #43 nationally. National Public Radio affiliate WUNC, based in Chapel Hill, has significant operations in Durham.

Transportation

Most travel in Durham is by private motor vehicle on its network of public streets and highways. Important arteries for traffic include NC 147, which connects Duke University, downtown, and Research Triangle Park, U.S. 15-501 between Durham and Chapel Hill, I-85, connecting Durham to Virginia and western North Carolina cities, and I-40 running across southern Durham County between the Research Triangle Park and Chapel Hill. The I-40 corridor has been the main site of commercial and residential development in Durham since its opening in the early 1990s. Over 95% of commuters use a car to get to work, with 14% of those people in carpools.[54]

Durham maintains an extensive network of bicycle routes and trails and has been recognized with a Bicycle Friendly Community Award.[55] The American Tobacco Trail begins in downtown and continues south through Research Triangle Park and ends in Wake County. The city is also considering furthering the progress on the Triangle Greenway System.

Air travel is serviced by Raleigh-Durham International Airport, 12 miles southeast of Durham, which enplanes about 4.5 million passengers per year.[56] Frequent service (5 flights a day or more) is available to Philadelphia, Atlanta, New York LaGuardia, New York Kennedy, Newark, Washington Reagan, Washington Dulles, Chicago O'Hare, Dallas, Houston, Miami, and Charlotte. Non-stop daily service is provided to approximately 30 destinations in the United States and daily international service is also available to London Heathrow, Toronto-Pearson and Paris Charles de Gaulle.

Amtrak operates a daily train between Charlotte and New York City (the Carolinian) which stops at the Durham Transit Station in downtown Durham. The State of North Carolina, in cooperation with Amtrak, operates two additional daily trains between Raleigh and Charlotte which also stop in Durham. Some of the downtown streets cross the tracks at grade level, while other intersections have grade separation. One downtown railroad underpass has attracted national media coverage, because it provides only 11 feet-8 inches of clearance, and has damaged the roofs of many trucks.[57]

National bus service is provided by Greyhound and Megabus at the Durham Transit Station in downtown Durham. GoDurham (formerly the Durham Area Transit Authority (DATA)) provides municipal bus service.

Triangle Transit (known formerly as the Triangle Transit Authority, or TTA) offers scheduled, fixed-route regional and commuter bus service between Raleigh and the region's other principal cities of Durham, Cary and Chapel Hill, as well as to and from the Raleigh-Durham International Airport, Research Triangle Park and several of the region's larger suburban communities. TT also coordinates an extensive vanpool and rideshare program that serves the region's larger employers and commute destinations.

From 1995, the cornerstone of Triangle Transit's long-term plan was a 28-mile (45 km) rail corridor from northeast Raleigh, through downtown Raleigh, Cary, and Research Triangle Park, to Durham using DMU technology. There were proposals to extend this corridor 7 miles (11 km) to Chapel Hill with light rail technology. However, in 2006 Triangle Transit deferred implementation indefinitely when the Federal Transit Administration declined to fund the program. Government agencies throughout the Raleigh-Durham metropolitan area have struggled with determining the best means of providing fixed-rail transit service for the region.

The region's two metropolitan planning organizations appointed a group of local citizens in 2007 to reexamine options for future transit development in light of Triangle Transit's problems. The Special Transit Advisory Commission (STAC) retained many of the provisions of Triangle Transit's original plan, but recommended adding new bus services and raising additional revenues by adding a new local half-cent sales tax to fund the project.[58]

Duke University also maintains its own transit system, Duke Transit operates more than 30 buses with routes throughout the campus and health system. Duke campus buses and vans have alternate schedules or do not operate during breaks and holidays. A new Greyhound bus and amtrak station was built in 2011 in downtown Durham.

In an effort to create safer roadways for vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians, drivers can enroll in Durham's Pace Car Program and agree to drive the speed limit, "stop at all stop signs", "stop at all red lights", "and stop to let pedestrians cross the street".[59]

Notable people

Born in Durham

- Ernie Barnes, artist/painter[60]

- Kara Medoff Barnett, theatre producer, arts director

- Bull City Red, blues musician

- Ben Brantley, New York Times theater critic

- Michael Brooks, NFL player

- Shirley Caesar, pastor and gospel recording artist

- Roger Lee Craig,[61] Major League Baseball pitcher

- Duffer Brothers, creators of the Netflix series Stranger Things

- Rick Ferrell, Hall of Fame baseball player[62]

- Penny Fuller, award-winning actress in numerous Broadway, film, and television productions

- David Garrard, NFL (2002–2013) quarterback

- David Gergen, advisor to presidents Ford, Reagan, and Clinton

- John H. Hager, former Virginia lieutenant governor (1998–2002) and the father-in-law of former First Daughter Jenna Bush Hager

- Brittany Hargest and Brandon Hargest, singers for Jump5

- Biff Henderson, Late Show with David Letterman comedian and television personality

- Wilbur Hobby, labor leader and former president of the North Carolina AFL-CIO

- Alexander Isley, designer and educator

- John P. Kee, pastor and gospel recording artist

- Little Brother, hip-hop group

- John D. Loudermilk, songwriter ("Tobacco Road", "Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye")

- John Lucas II, NBA player and coach

- Crystal Mangum, accuser in the 2006 Duke lacrosse case,[63] who was later found guilty of fatally stabbing her boyfriend[64]

- Pigmeat Markham, comic actor and novelty musician

- Frank Matthews, major heroin and cocaine trafficker who operated throughout the eastern seaboard during the late 1960s and early 1970s

- Clyde McPhatter, singer/songwriter, founding member of The Drifters.

- LeRoi Moore of the Dave Matthews Band, contemporary jazz musician

- Anita Morris, actress (Ruthless People, The Hotel New Hampshire, nominated for a Tony for her work in Nine)

- David Noel, NBA player for the Milwaukee Bucks[65]

- Ike Opara, Major League Soccer defender for Sporting Kansas City

- Brian Roberts, current Major League Baseball player, second baseman for the Baltimore Orioles[66]

- Rodney Rogers,[67] NBA (1993–2005) power forward

- Ben Ruffin, civil rights activist, educator, and businessman

- Don Schlitz, songwriter (Kenny Rogers's "The Gambler")

- Robert K. Steel, former Undersecretary of the Treasury

- Andre Leon Talley, Vogue editor, fashion luminary, and current judge of ANTM

- Emilie Townes, dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School, former president of the American Academy of Religion[68]

- Dewayne Washington, NFL (1994–2005) cornerback

- Seth Wescott,[69] Olympic champion snowboarder

- Josh Whitesell, Major League Baseball first baseman of the Arizona Diamondbacks[70]

- Walter Lee Williams, one of the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives[71]

- Morgan Wootten, legendary head basketball coach at DeMatha Catholic High School and member of the Basketball Hall of Fame

Residents of Durham

- Ann Atwater, civil rights activist in Durham

- Samuel Beam, singer/songwriter from Iron & Wine, current resident

- John Darnielle, an American musician and novelist best known as the primary (and often solitary) member of the American band the Mountain Goats, for which he is the writer, composer, guitarist, pianist, and vocalist.[72]

- Nnenna Freelon, jazz singer/composer

- Philip Freelon, Architect. Designer of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Michael Hardt, philosopher and theorist of globalization, politics and culture

- Fredric Jameson, literary critic and Marxist political theorist

- Big Daddy Kane, hip-hop artist and actor[73]

- Mur Lafferty, podcaster and writer

- Pura Fe, Native American singer

- John Malachi, jazz pianist[74]

- Branford Marsalis has been a resident of Durham for several years. The Branford Marsalis Quartet's 2006 album Braggtown was titled after Braggtown Baptist Church, located in northeastern Durham, just north of Highways 70/85.[75]

- Pauli Murray, civil rights and women's activist, attorney, author, poet and priest, lived here as a child with grandparents. In 1977 she was the first black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest and in 2012 named as an Episcopal saint (one of its Holy Women, Holy Men).

- Mike Nifong, Durham County district attorney disbarred in 2006 for actions in Duke University lacrosse case that year[76]

- Leah Roberts, former North Carolina State University student who abruptly left Durham in March 2000 and has remained missing ever since

- The Mountain Goats, an indie rock band

- LeRoy T. Walker (June 14, 1918 – April 23, 2012), former United States Olympic president and former chancellor of North Carolina Central University (NCCU)[77]

- Jamie Stewart, art-pop musician best known as the frontman of Xiu Xiu[78]

- Mike Krzyzewski, head coach of the Duke Men's Basketball team, head coach of Team USA

Associated with Durham

- Fulton Allen ("Blind Boy Fuller"), musician

- Andrew Britton, novelist

- Carolina Chocolate Drops, folk band who cite their hometown as Durham

- Rev. Gary Davis, musician

- Whitey Durham, coach in the hit CW network drama One Tree Hill, set in the fictional Tree Hill, North Carolina, was named after Durham

- Ezekiel Giles ("Freekey Zekey"), rapper. Spent almost three years in jail at Durham Correctional Center on drug charges before being released on November 20, 2006.[79][80]

- David Lynch, film and TV director. Lived in Durham as a child, parents met at Duke University.[81]

- Doug Marlette, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist. Lived in Durham as a child.[82]

Sister cities

Durham has five sister cities:[83]

Arusha, Arusha Region, Tanzania

Arusha, Arusha Region, Tanzania Durham, County Durham, England, United Kingdom

Durham, County Durham, England, United Kingdom Kostroma, Kostroma Oblast, Russia

Kostroma, Kostroma Oblast, Russia Toyama, Toyama Prefecture, Japan

Toyama, Toyama Prefecture, Japan Zhuzhou, Hunan, China

Zhuzhou, Hunan, China

See also

References

- ↑ "About Durham". Archived from the original on October 22, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- 1 2 Durham (N.C.) – Directories. Richmond, Virginia: Hill Directory Company. 1923. p. 7. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of Resident Population Change for Incorporated Places 2010 to 2013". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Population Estimates 2012 Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Where is RTP?". The Herald Sun reports that it is the 4th smartest city in the USA. Research Triangle Foundation of North Carolina. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Durham". durhamnc.gov. Durham City Government. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ↑ "This day in 1914". Web page. Museum of Durham History. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ "History". Carolina Theatre. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "NC Finally Recognizes Pre-Woolworth Sit-Ins In 1956". Greensboro3.com. January 19, 2008. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009.

- ↑ "Dedication of the 1957 Royal Ice Cream sit-in historical marker". Terra Sigillata. November 29, 2009. Archived from the original on August 16, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ↑ "G-123 Royal Ice Cream Sit-In". North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ↑ Ehrsam, Frederick. "The downfall of Durham’s historic Hayti: Propagated or preempted by urban renewal?" (PDF).

- ↑ "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ↑ Contributor Guidelines (September 21, 2010). "Durham". Ourstate.com. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "City of Durham - Office of Economic and Workforce Development". Durhamnc.gov. October 7, 2010. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "American Tobacco Campus Web Site". Americantobaccohistoricdistrict.com. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ McGee, Matt (September 26, 2013). "The Google Glass Road Show Starts October 5th in Durham, NC". Glass Almanac. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "New Visitor Developments Chart". Durham, NC. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Ingrid K. (January 17, 2013). "36 Hours in Durham, N.C". The New York Times.

- ↑ "mercurystudiodurham.com". mercurystudiodurham.com. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ 21c Museum Hotels (June 28, 2013). "Downtown Durham NC | Opening 2015". 21c Museum Hotels. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Construction set to begin on downtown Durham tower". newsobserver. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Durham, Raleigh ready for new 26- and 23-story buildings". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Durham city, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Climatology of the United States No. 20: DURHAM, NC 1971–2000" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Durham, NC (27703)". The Weather Channel. November 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Economic Profile - Greater Durham Chamber of Commerce | Large Employers/Manufacturers and Headquarters". Greater Durham Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ St. Joseph’s Historic Foundation (January 22, 2016). "2015 Bull Durham Blues Festival". Durham Central Park. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Merge Records - CDs and Vinyl". Discogs.com. August 19, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Barry Poss Discography". Discogs.com. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "DISCORDER Farewell, Mr. Lady". Web.archive.org. September 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Introduction". Bullcitysoul.org. February 3, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Artistic Durham". Weebly.com. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Favat, Brian (May 18, 2009). "Headlines: Men's Basketball Attendance Ranked 99th Nationally". BC Interruption. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "NCAA College Basketball Tournament Winners and Final Four Teams". Fanbay.net. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Durham County : Board of Elections" (PDF). Co.durham.nc.us. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Durham, NC - City of Medicine". Durhamnc.gov. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ Archived May 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived February 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Yardley, William (May 3, 2006). "Prosecutor in Duke Case Wins Election". The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ "City of Medicine Academy". Choice.dpsnc.net. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Retrieved May 9, 2011". Privateschoolreview.com. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "In Pictures: Top 20 Places To Educate Your Child". Forbes. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Where To Educate Your Children". Forbes. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Retrieved May 9, 2011". Newsoffice.duke.edu. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Work and Jobs in Durham, North Carolina (NC) Detailed Stats: Occupations, Industries, Unemployment, Workers, Commute". City-data.com. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Cycling group Durham Bicycle Friendly". The Herald-Sun. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Raleigh-Durham International Airport in Durham, North Carolina - Elevation, Runways, Altitude". City-data.com. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ Tamara Gibbs (June 22, 2015). "Trucks hit same Durham bridge hours apart". Eyewitness News.

- ↑ "Regional Transit Infrastructure Blueprint". Transitblueprint.org. May 21, 2008. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "City of Durham Pace Car Project" (PDF). Douthit.biz. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- ↑ "Ernie Barnes". ErnieBarnes.com. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ "Roger Lee Craig". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ "Rick Ferrell". The Baseball Page. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ "Crystal Gail Mangum: Profile of the Duke Rape Accuser". FoxNews.com. April 11, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ WRAL (2013-11-22). "Mangum found guilty in boyfriend's stabbing death :: WRAL.com". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ "David Noel". Mahalo.com. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Brian Roberts Statistics". Sports Reference, Inc. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Rodney Rogers". Basketball-Reference.Com. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Bio | People | Divinity School | Vanderbilt University". divinity.vanderbilt.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- ↑ "Rick Ferrell". United States Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ "Josh Whitesell Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ↑ "FBI — Homepage". Fbi.gov. May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ Hoard, Christian. "The Slow Climb: How the Mountain Goats' John Darnielle Became the Best Storyteller in Rock.", Rolling Stone, April 7, 2015. Web. April 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Big Daddy Kane, The Jay-Z Of '89, Still Every Bit The Playa". MTV News. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ Rinzler, Paul; Kernfeld, Barry, Malachi, John, Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, retrieved July 25, 2015, (Subscription required (help))

- ↑ "Branford's bragging rights". News and Observer. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ↑ Neff, Joseph (August 6, 2006). "Lacrosse files show gaps in DA's case". News & Observer. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006.

- ↑ "LeRoy Walker Bio". US Track and Field Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ↑ Haver, Grayson. "The travails of Xiu Xiu leader and reluctant Durham resident Jamie Stewart | Music Essay". Indy Week. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ Winn, Patrick. "'Freaky Zekey' free from prison" Archived January 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., The News & Observer, November 21, 2006. Accessed April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Freaky Zekey Released From Prison" Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., HHNLive.com, November 21, 2006. Accessed April 5, 2007.

- ↑ Rodley, Chris; Lynch, David (2005). Lynch on Lynch (2nd ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 0-571-22018-5.

- ↑ "Cartoonist Doug Marlette dies in wreck". Raleigh News and Observer. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ "Sister Cities of Durham". Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

Further reading

- Turner & Co.'s Durham directory for the years 1889 and 1890, Danville, Va: E.F. Turner, 1889

- Ramsey's Durham directory, for the year 1892, Durham, N.C: N.A. Ramsey, 1892

External links

-

Geographic data related to Durham, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Durham, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap - Official website

- Durham County Government

- Downtown Durham, Inc.

- Durham Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Durham County Library

- Durham Public Schools

- Greater Durham Chamber of Commerce

- Digital Durham Exploring and chronicling the history of post-Civil War Durham

- Endangered Durham Website with history and many before-and-after pictures of architecture in Durham

- Durham Downtown Merchants Association

- North Carolina Room of the Durham County Library Website for an archive which collects materials concerning the city and county of Durham