Dryptosaurus

| Dryptosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 67 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Elements of the type specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Tyrannosauroidea |

| Family: | †Dryptosauridae Marsh, 1890 |

| Genus: | †Dryptosaurus Marsh, 1877 |

| Species: | †D. aquilunguis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Cope, 1866 [originally Laelaps]) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Laelaps aquilunguis Cope, 1866 (preoccupied) | |

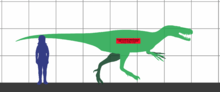

Dryptosaurus (/ˌdrɪptoʊˈsɔːrəs/ DRIP-toh-SAW-rəs) is a genus of primitive tyrannosauroid that lived approximately 67 million years ago during the latter part of the Cretaceous period in what is now Eastern North America. Dryptosaurus was a large, bipedal, ground-dwelling carnivore, that could grow up to 7.5 m (24.6 ft) long. Although largely unknown now outside of academic circles, a famous painting of the genus by Charles R. Knight made it one of the more widely known dinosaurs of its time, in spite of its poor fossil record. First described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1866 and later renamed by Othniel C. Marsh in 1877, Dryptosaurus is among the first theropod dinosaurs known to science.

Description

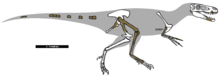

Dryptosaurus is estimated to have been 7.5 metres (24.6 ft) long and to have weighed 1.5 metric tons (1.7 short tons), although this is based on partial remains of one individual.[1] Like its relative Eotyrannus, Dryptosaurus seems to have had relatively long arms when compared with more derived tyrannosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus. Its hands, which are also relatively large were believed to have had three fingers. Brusatte et al. (2011), however, observed an overall similarity in the shape of the available phalanges of Dryptosaurus with those of derived tyrannosaurids and noted that Dryptosaurus may have had only two functional digits.[2] Each of its fingers were tipped by a talonlike 8 inch claw.[3] Its forelimb morphology suggests that forelimb reduction in tyrannosauroids may not have proceeded in a uniform fashion.[2] Dryptosaurus may have used both its arms and its jaws and as weapons when hunting, capturing and processing prey.[2] The type specimen is a fragmentary skeleton belonging to a single adult individual. ANSP 9995 consists of a fragmentary right maxilla, a fragmentary right dentary, a fragmentary right surangular, lateral teeth, 11 middle-distal caudal vertebrae, both the left and right humeri, three manual phalanges from the left hand (I-1, II-2, and an ungual), the shafts of the left and right pubis bones, a fragmentary right ischium, the left femur, the left tibia, the left fibula, the left astragalus, and a midshaft fragment of metatarsal III. The ontological maturity of the holotype individual is supported by the fact that the neurocentral sutures are closed in all of its caudal vertebrae.[2] AMNH FARB 2438 consists of left metatarsal IV, which are likely from the same individual as the holotype.[4]

The fragmentary right maxilla preserves the three alveoli in full and the fourth only partially. The authors were able to ascertain that Dryptosaurus had ziphodont dentition. The shape of the alveolus situated on the anterior portion of the fragment suggests that it housed a tooth that was smaller and more circular than the others; an incisiform tooth which is common in tyrannosauroids. The disarticulated teeth recovered are transversely narrow, serrated (17-18 denticles/cm) and recurved. The femur is only 3% longer than the tibia. The longest manual ungual phalanx recovered measured 176 mm (6.9 in) in length. The morphology of the proximal portion of metatarsal IV suggests that Dryptosaurus had an arctometatarsalian foot, an advanced feature shared by derived tyrannosauroids such as Albertosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, in which the third metatarsal is “pinched” between the second and fourth metatarsals.

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism or group. According to Brusatte et al. (2011), Dryptosaurus can be distinguished based on the following characteristics: the combination of a reduced humerus (humerus: femur ratio = 0.375) and a large hand (phalanx I-1:femur ratio = 0.200), the strong mediolateral expansion of the ischial tubercle, which is approximately 1.7 times as wide as the shaft immediately distally, the presence of an ovoid fossa on the medial surface of the femoral shaft immediately proximal to the medial condyle, which is demarcated anteriorly by the mesiodistal crest and demarcated medially by a novel crest, the presence of a proximomedially trending ridge on the anterior surface of the fibula immediately proximal to the iliofibularis tubercle, the lip on the lateral surface of the lateral condyle of the astragalus is prominent and is overlapping the proximal surface of the calcaneum, metatarsal IV is observed with a flat shaft proximally, resulting in a semiovoid cross section that is much wider mediolaterally than it is long anteroposteriorly.

Discovery and species

Prior to the discovery of Dryptosaurus in 1866, New World theropods were known only from some isolated theropod teeth discovered in Montana by Joseph Leidy in 1856.[5] The discovery of this genus gave North American paleontologists the opportunity to observe an articulated, albeit incomplete, theropod skeleton. During the 19th century, this genus unfortunately became a wastebasket taxon for the referral of isolated theropod elements from across North America given that tyrannosauroids were not recognized as a distinct group of large theropods in the late 19th century, and numerous theropod species were assigned to it (often as Lælaps or Laelaps) only to be later reclassified.

The genus name Dryptosaurus, means "tearing lizard", and is derived from the Greek words "dryptō" (δρύπτω), meaning "I tear" and "sauros" (σαυρος) meaning "lizard".[6] The specific name aquilunguis, is derived from the Latin for "having claws like an eagle's", a reference to the claws on its three-fingered hand. E. D. Cope (1866) published a paper on the specimen within a week of its discovery, and christened it Laelaps aquilunguis at a meeting of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.[2] "Laelaps", which is derived from the Greek for “hurricane” or “storm wind”, was also the name of a dog in Greek mythology that never failed to catch what it was hunting.[7] Laelaps gained popularity as both a poetic and evocative name and became one of the first dinosaurs described from North America, following Hadrosaurus, Aublysodon and Trachodon. Later it was discovered that the name Laelaps had already been given to a genus of mite, and Cope's lifelong rival O.C. Marsh changed the name in 1877 to Dryptosaurus. The type species is Dryptosaurus aquilunguis.

Brusatte et al. (2011) noted that well-preserved, historic casts of most of the type material ANSP 9995/AMNH FARB 2438 are housed in the collections of the Natural History Museum in London (NHM OR50100). The casts show some detail that is no longer preserved on the original specimens which have significantly degraded due to pyrite disease.[8]

Misassigned species

Laelaps trihedrodon was coined by Cope in 1877 for a partial dentary (now missing) from the Morrison Formation of Colorado. Five damaged partial tooth crowns (AMNH 5780) mistakenly thought to have belonged to the L. trihedrodon holotype share many features in common with Allosaurus and probably belong to that genus. However some of the Allosaurus-like characters of the teeth are primitive to theropods as a whole and may have been present in other large-bodied Morrison Formation theropod species. [9]

"Laelaps" macropus was coined by Cope for a partial hind limb found in the Navesink Formation that Joseph Leidy had referred earlier to the ornithomimid Coelosaurus, distinguishing it from Dryptosaurus by its longer toes.[10] Thomas R. Holtz listed it as an indeterminate tyrannosauroid in his contribution to the second condition of the Dinosauria.[11] In 2017, it was given the new generic name Teihivenator.[12]

Classification

Since the time of its discovery, Dryptosaurus has been classified in a number of theropod families. Cope (1866), Leidy (1868) and Lydekker (1888) noted obvious similarities with the genus Megalosaurus which was known at the time from remains discovered in southeastern England. Based on this line of reasoning, Cope classified it as a megalosaurid. Marsh, however, examined the remains and later assigned to its own monotypic family, Dryptosauridae. The fossil material assigned to Dryptosaurus was reviewed by Ken Carpenter in 1997 in light of the many different theropods discovered since Cope's day. He felt that due to some unusual features it couldn't be placed in any existing family, and like Marsh, felt that it warranted placement in Dryptosauridae.[4] This phylogenetic assignment was also supported by the work of Russell (1970) and Molnar (1990).[13][14] Other phylogenetic studies during the 1990s suggested that Dryptosaurus was a coelurosaur, though its exact placement within that group remained uncertain.

In 1946, Charles W. Gilmore was the first to observe that certain anatomical features may link Dryptosaurus with coeval Late Cretaceous tyrannosaurids, Albertosaurus and Tyrannosaurus.[15] This observation was also supported by the work of Baird and Horner (1979), but did not have wide acceptance until a new discovery was made in 2005.[16] Dryptosaurus was the only large carnivore known in eastern North America until the discovery of the basal tyrannosauroid Appalachiosaurus in 2005.[17] Appalachiosaurus which is known from more complete remains, is similar to Dryptosaurus in both body size and morphology.[18] This discovery made it clear that Dryptosaurus was a primitive tyrannosauroid. Detailed phylogenetic analysis by Brusatte et al. (2011) confirmed the tyrannosauroid affinities of Dryptosaurus and assigned it as an “intermediate” tyrannosauroid that is more derived than basal taxa such as Guanlong and Dilong, but more primitive than members of the more derived Tyrannosauridae.[19]

The following cladogram containing almost all tyrannosauroids is by Loewen et al. (2013).[20]

| Tyrannosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The type specimen of Dryptosaurus ANSP 9995 was recovered in the West Jersey Marl Company Pit, in what came to be known as the New Egypt Formation in Barnsboro, in Gloucester County, New Jersey. The specimen was collected by quarry workers in marl and sandstone that were deposited during the Maastrichtian stage of the Cretaceous period, approximately 67 million years ago.[3][21]

Studies suggest that the New Egypt Formation is a marine unit, and it is considered to be the deeper-water equivalent of the Tinton and Red Bank formations.[22] This formation overlies the Navesink Formation, from which potential Dryptosaurus referred material has been reported.

During the Maastrichtian stage the Western Interior Seaway, which stretched in a north-south direction from the present-day Arctic Ocean down to the Gulf of Mexico, separated Dryptosaurus and its coeval fauna from western North America which was dominated by tyrannosaurids. Although certainly a carnivore, the paucity of known Cretaceous East Coast dinosaurs make ascertaining the specific diet of Dryptosaurus difficult.[3] Hadrosaurids are known from the same time and place as Dryptosaurus, the island continent of Appalachia, and they may have been a prominent part of its diet. Nodosaurs were also present, although less likely to be hunted due to their armor plating.[3] When hunting, both the skull and hands were important for the capture and processing of prey.

Cultural significance

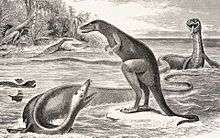

The 1896 watercolor painting (right) by Charles R. Knight titled “Leaping Laelaps” may represent the earliest depiction of theropods as highly active and dynamic. Knight's hand was guided by E. D. Cope, and reflects their progressive opinion about theropod agility despite their large size, as well as the opinion of Henry Fairfield Osborn, the curator of vertebrate paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History at the time of the painting's commission. The original painting is now preserved in the AMNH collections. By contrast, the typical illustrations of large carnivorous dinosaurs like Megalosaurus, in the late 1800s, depicted the animals as large, tail-dragging behemoths.

Currently efforts are underway by Gary Vecchiarelli of Project: Dryptosaurus to get a mount of the skeleton established in a more permanent location hosted in New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. Project: Dryptosaurus was established as a non-profit organization dedicated to educating the public and scientific community about the world’s forgotten second dinosaur skeleton from New Jersey, and thus resurrecting this specimen to its rightful position in the chronology of dinosaur discoveries. The Project’s backers and supporters include respected professionals in the paleo-community. The Project has been featured in Prehistoric Times magazine in Issue #94 and Weird New Jersey in Issue #34. Project: Dryptosaurus overall is dedicated to advancing the science of dinosaur paleontology as well and is currently working on non-profit status as indicated on the website.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brusatte, S. L. and Benson, R. B. J. and Norell, M. A. (2011) The Anatomy of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and a Review of its Tyrannosauroid Affinities. American Museum Novitates, 3717 . pp. 1-53. ISSN 0003-0082

- 1 2 3 4 Dryptosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 112-113

- 1 2 Carpenter, Ken & Russell, Dale A, Donald Baird, and R. Denton (1997). "Redescription of the holotype of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of New Jersey". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (3): 561–573. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011003. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Leidy, J. 1856. Notice of remains of extinct reptiles and fishes discovered by Dr. F. V. Hayden in the badlands of the Judith River, Nebraska Territory. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 8: 72–73.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ Cope, E.D. (1866). "Discovery of a gigantic dinosaur in the Cretaceous of New Jersey". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 18: 275–279.

- ↑ Spamer, E.E., E. Daeschler, and L.G. Vostreys-Shapiro. 1995. A study of fossil vertebrate types in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Special Publication 16, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

- ↑ Chure, Daniel J. (2001). "On the type and referred material of Laelaps trihedrodon Cope 1877 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". In Tanke, Darren; and Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 10–18. ISBN 978-0-253-33907-2.

- ↑ Cope, E.D., On the genus Laelaps, American Journal of Science, 1868; 2: 415-417.

- ↑ Holtz, T.R. (2004). "Tyrannosauroidea." Pp. 111-136 in Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska (eds). The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley.

- ↑ Chan-gyu Yun (2017). "Teihivenator gen. nov., a new generic name for the tyrannosauroid dinosaur "Laelaps" macropus (Cope, 1868; preoccupied by Koch, 1836)". Journal of Zoological And Bioscience Research. 4 (2): 7–13. doi:10.24896/jzbr.2017422.

- ↑ Russell, D.A. 1970. Tyrannosauroids from the Late Cretaceous of western Canada. National Museum of Natural Science (Ottawa) Publications in Paleontology 1: 1–34.

- ↑ Molnar, R.E. 1990. Problematic Theropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmólska (editors), The Dinosauria: 306–317. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Gilmore, C.W. 1946. A new carnivorous dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Montana. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 106: 1–19.

- ↑ Baird, D., and J. Horner. 1979. Cretaceous dinosaurs (Reptilia) of North Carolina. Brimleyana 2: 1–18.

- ↑ Carr, T.D.; Williamson, T.E. & Schwimmer, D.R. (2005). "A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 119–143. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0119:ANGASO]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Holtz, T.R. 2004. Tyrannosauroidea. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmólska (editors), The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.: 111–136. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Brusatte, S.L.; Benson, R.B.J. "The systematics of Late Jurassic tyrannosauroids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Europe and North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58: 47–54.

- ↑ Loewen, M.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, David C, ed. "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79420. PMC 3819173

. PMID 24223179. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420.

. PMID 24223179. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420. - ↑ Olsson, R.K. (1960). "Foraminifera of latest Cretaceous and earliest Tertiary age in the New Jersey coastal plain". Journal of Paleontology. 34: 1–58.

- ↑ Olsson, R.K. 1987. Cretaceous stratigraphy of the Atlantic coastal plain, Atlantic highlands of New Jersey. Geological Society of America Centennial Field Guide–Northeastern Section: 87–90.

- ↑ ERVOLINO, BILL (April 13, 2010). "This dinosaur had a Jersey attitude". THE RECORD. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Carr and Williamson (2002). "Evolution of basal Tyrannosauroidea from North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 41A.

- - Cretaceous Dinosaurs of the Southeastern United States by David T. King Jr.