Route of administration

A route of administration in pharmacology and toxicology is the path by which a drug, fluid, poison, or other substance is taken into the body.[1] Routes of administration are generally classified by the location at which the substance is applied. Common examples include oral and intravenous administration. Routes can also be classified based on where the target of action is. Action may be topical (local), enteral (system-wide effect, but delivered through the gastrointestinal tract), or parenteral (systemic action, but delivered by routes other than the GI tract).

Classification

Routes of administration are usually classified by application location (or exposition).

The route or course the active substance takes from application location to the location where it has its target effect is usually rather a matter of pharmacokinetics (concerning the processes of uptake, distribution, and elimination of drugs). Exceptions include the transdermal or transmucosal routes, which are still commonly referred to as routes of administration.

The location of the target effect of active substances are usually rather a matter of pharmacodynamics (concerning e.g. the physiological effects of drugs[2]). An exception is topical adminstration, which generally means that both the application location and the effect thereof is local.[3]

Topical administration is sometimes defined as both a local application location and local pharmacodynamic effect,[3] and sometimes merely as a local application location regardless of location of the effects.[4][5]

By application location

Enteral/gastrointestinal

.jpg)

Administration through the gastrointestinal tract is sometimes termed enteral or enteric administration (literally meaning 'through the intestines'). Enteral/enteric administration usually includes oral[6] (through the mouth) and rectal (into the rectum)[6] administration, in the sense that these are taken up by the intestines. However, uptake of drugs administered orally may also occur already in the stomach, and as such gastrointestinal (along the gastrointestinal tract) may be a more fitting term for this route of administration. Furthermore, some application locations often classified as enteral, such as sublingual[6] (under the tongue) and sublabial or buccal (between the cheek and gums/gingiva), are taken up in the proximal part of the gastrointestinal tract without reaching the intestines. Strictly enteral administration (directly into the intestines) can be used for systemic administration, as well as local (sometimes termed topical), such as in a contrast enema, whereby contrast media is infused into the intestines for imaging. However, for the purposes of classification based on location of effects, the term enteral is reserved for substances with systemic effects.

Many drugs as tablets, capsules, or drops are taken orally. Administration methods directly into the stomach include those by gastric feeding tube or gastrostomy. Substances may also be placed into the small intestines, as with a duodenal feeding tube and enteral nutrition. Enteric coated tablets are designed to dissolve in the intestine, not the stomach, because the drug present in the tablet causes irritation in the stomach.

The rectal route is an effective route of administration for many medications, especially those used at the end of life.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] The walls of the rectum absorb many medications quickly and effectively.[14] Medications delivered to the distal one-third of the rectum at least partially avoid the "first pass effect" through the liver, which allows for greater bio-availability of many medications than that of the oral route. Rectal mucosa is highly vascularized tissue that allows for rapid and effective absorption of medications.[15] A suppository is a solid dosage form that fits for rectal administration. In hospice care, a specialized rectal catheter, designed to provide comfortable and discreet administration of ongoing medications provides a practical way to deliver and retain liquid formulations in the distal rectum, giving health practitioners a way to leverage the established benefits of rectal administration.

Parenteral

The parenteral route is any route that is not enteral (par- + enteral).

Parenteral adminstration can be performed by injection, that is, using a needle (usually a hypodermic needle) and a syringe,[16] or by the insertion of an indwelling catheter.

Locations of application of parenteral administration include:

- Central nervous system

- epidural (synonym: peridural) (injection or infusion into the epidural space), e.g. epidural anesthesia

- intracerebral (into the cerebrum) direct injection into the brain. Used in experimental research of chemicals[17] and as a treatment for malignancies of the brain.[18] The intracerebral route can also interrupt the blood brain barrier from holding up against subsequent routes.[19]

- intracerebroventricular (into the cerebral ventricles) administration into the ventricular system of the brain. One use is as a last line of opioid treatment for terminal cancer patients with intractable cancer pain.[20]

- Epicutaneous (application onto the skin). It can be used both for local effect as in allergy testing and typical local anesthesia, as well as systemic effects when the active substance diffuses through skin in a transdermal route.

- Sublingual and buccal medication administration is a way of giving someone medicine orally (by mouth). Sublingual administration is when medication is placed under the tongue to be absorbed by the body. The word "sublingual" means "under the tongue." Buccal administration involves placement of the drug between the gums and the cheek. These medications can come in the form of tablets, films, or sprays. Many drugs are designed for sublingual administration, including cardiovascular drugs, steroids, barbiturates, opioid analgesics with poor gastrointestinal bioavailability, enzymes and, increasingly, vitamins and minerals.

- extra-amniotic administration, between the endometrium and fetal membranes

- nasal administration (through the nose) can be used for topically acting substances, as well as for insufflation of e.g. decongestant nasal sprays to be taken up along the respiratory tract. Such substances are also called inhalational, e.g. inhalational anesthetics.

- intraarterial (into an artery), e.g. vasodilator drugs in the treatment of vasospasm and thrombolytic drugs for treatment of embolism

- intraarticular, into a joint space. Used in treating osteoarthritis

- intracardiac (into the heart), e.g. adrenaline during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (no longer commonly performed)

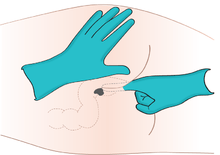

- Intracavernous injection, an injection into the base of the penis

- intradermal, (into the skin itself) is used for skin testing some allergens, and also for mantoux test for tuberculosis

- Intralesional (into a skin lesion), is used for local skin lesions, e.g. acne medication

- intramuscular (into a muscle), e.g. many vaccines, antibiotics, and long-term psychoactive agents. Recreationally the colloquial term 'muscling' is used.[21]

- Intraocular, into the eye, e.g., some medications for glaucoma or eye neoplasms

- intraosseous infusion (into the bone marrow) is, in effect, an indirect intravenous access because the bone marrow drains directly into the venous system. This route is occasionally used for drugs and fluids in emergency medicine and pediatrics when intravenous access is difficult. Recreationally the colloquial term 'boning' is used.[21]

- intraperitoneal, (infusion or injection into the peritoneum) e.g. peritoneal dialysis

- intrathecal (into the spinal canal) is most commonly used for spinal anesthesia and chemotherapy

- Intrauterine

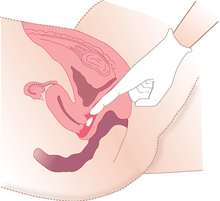

- Intravaginal administration, in the vagina

- intravenous (into a vein), e.g. many drugs, total parenteral nutrition

- Intravesical infusion is into the urinary bladder.

- intravitreal, through the eye

- Subcutaneous (under the skin).[22] This generally takes the form of subcutaneous injection, e.g. with insulin. Skin popping is a slang term that includes subcutaneous injection, and is usually used in association with recreational drugs. In addition to injection, it is also possible to slowly infuse fluids subcutaneously in the form of hypodermoclysis.

- transdermal (diffusion through the intact skin for systemic rather than topical distribution), e.g. transdermal patches such as fentanyl in pain therapy, nicotine patches for treatment of addiction and nitroglycerine for treatment of angina pectoris.

- perivascular administration (perivascular medical devices and perivascular drug delivery systems are conceived for local application around a blood vessel during open vascular surgery). [23]

- Transmucosal (diffusion through a mucous membrane), e.g. insufflation (snorting) of cocaine, sublingual, i.e. under the tongue, sublabial, i.e. between the lips and gingiva, nitroglycerine, vaginal suppositories

Topical

The definition of the topical route of administration sometimes states that both the application location and the pharmacodynamic effect thereof is local.[3]

In other cases, topical is defined as applied to a localized area of the body or to the surface of a body part regardless of the location of the effect.[4][5] By this definition, topical administration also includes transdermal application, where the substance is administered onto the skin but is absorbed into the body to attain systemic distribution.

If defined strictly as having local effect, the topical route of administration can also include enteral administration of medications that are poorly absorbable by the gastrointestinal tract. One poorly absorbable antibiotic is vancomycin, which is recommended by mouth as a treatment for severe Clostridium difficile colitis.[24]

Choice of routes

The reason for choice of routes of drug administration are governing by various factors:

- Physical and chemical properties of the drug. The physical properties are solid, liquid and gas. The chemical properties are solubility, stability, pH, irritancy etc.

- Site of desired action: the action may be localised and approachable or generalised and not approachable.

- Rate of extent of absorption of the drug from different routes.

- Effect of digestive juices and the first phase of metabolism.

- Condition of the patient.

In acute situations, in emergency medicine and intensive care medicine, drugs are most often given intravenously. This is the most reliable route, as in acutely ill patients the absorption of substances from the tissues and from the digestive tract can often be unpredictable due to altered blood flow or bowel motility.

Conveniency

Enteral routes are generally the most convenient for the patient, as no punctures or sterile procedures are necessary. Enteral medications are therefore often preferred in the treatment of chronic disease. However, some drugs can not be used enterally because their absorption in the digestive tract is low or unpredictable. Transdermal administration is a comfortable alternative; there are, however, only a few drug preparations that are suitable for transdermal administration.

Desired target effect

Identical drugs can produce different results depending on the route of administration. For example, some drugs are not significantly absorbed into the bloodstream from the gastrointestinal tract and their action after enteral administration is therefore different from that after parenteral administration. This can be illustrated by the action of naloxone (Narcan), an antagonist of opiates such as morphine. Naloxone counteracts opiate action in the central nervous system when given intravenously and is therefore used in the treatment of opiate overdose. The same drug, when swallowed, acts exclusively on the bowels; it is here used to treat constipation under opiate pain therapy and does not affect the pain-reducing effect of the opiate.

Oral

The oral route is generally the most convenient and costs the least.[25] However, some drugs can cause gastrointestinal tract irritation.[26] For drugs that come in delayed release or time-release formulations, breaking the tablets or capsules can lead to more rapid delivery of the drug than intended.[25]

Local

By delivering drugs almost directly to the site of action, the risk of systemic side effects is reduced.[25] However, skin irritation may result, and for some forms such as creams or lotions, the dosage is difficult to control.[26]

Inhalation

Inhaled medications can be absorbed quickly and act both locally and systemically.[26] Proper technique with inhaler devices is necessary to achieve the correct dose. Some medications can have an unpleasant taste or irritate the mouth.[26]

Inhalation by smoking a substance is likely the most rapid way to deliver drugs to the brain, as the substance travels directly to the brain without being diluted in the systemic circulation.[27] The severity of dependence on psychoactive drugs tends to increase with more rapid drug delivery.[27]

Parenteral

The term injection encompasses intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous (SC) and intradermal (ID) administration.[28]

Parenteral adminstration generally acts more rapidly than topical or enteral adminstration, with onset of action often occurring in 15–30 seconds for IV, 10–20 minutes for IM and 15–30 minutes for SC.[29] They also have essentially 100% bioavailability and can be used for drugs that are poorly absorbed or ineffective when they are given orally.[25] Some medications, such as certain antipsychotics, can be administered as long-acting intramuscular injections.[30] Ongoing IV infusions can be used to deliver continuous medication or fluids.[31]

Disadvantages of injections include potential pain or discomfort for the patient and the requirement of trained staff using aseptic techniques for administration.[25] However, in some cases, patients are taught to self-inject, such as SC injection of insulin in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. As the drug is delivered to the site of action extremely rapidly with IV injection, there is a risk of overdose if the dose has been calculated incorrectly, and there is an increased risk of side effects if the drug is administered too rapidly.[25]

Research

Neural drug delivery is the next step beyond the basic addition of growth factors to nerve guidance conduits. Drug delivery systems allow the rate of growth factor release to be regulated over time, which is critical for creating an environment more closely representative of in vivo development environments.[32]

See also

- ADME

- Catheter

- Dosage form

- Drug injection

- Hypodermic needle

- Intravenous marijuana syndrome

- List of medical inhalants

- Nanomedicine

References

- ↑ TheFreeDictionary.com > route of administration Citing: Jonas: Mosby's Dictionary of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005, Elsevier.

- ↑ Lees P, Cunningham FM, Elliott J (2004). "Principles of pharmacodynamics and their applications in veterinary pharmacology". J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 27 (6): 397–414. PMID 15601436. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2004.00620.x.

- 1 2 3 "topical". Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- 1 2 thefreedictionary.com > topical Citing: The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000

- 1 2 "topical". dictionary.com. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- 1 2 3 "Oklahoma Administrative Code and Register > 195:20-1-3.1. Pediatric conscious sedation utilizing enteral methods (oral, rectal, sublingual)". Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ Davis MP, Walsh D, LeGrand SB, Naughton M (2002). "Symptom control in cancer patients: the clinical pharmacology and therapeutic role of suppositories and rectal suspensions". Support Care Cancer. 10 (2): 117–38. PMID 11862502. doi:10.1007/s00520-001-0311-6.

- ↑ De Boer AG, Moolenaar F, de Leede LG, Breimer DD (1982). "Rectal drug administration: clinical pharmacokinetic considerations". Clin Pharmacokinetics. 7 (4): 285–311. PMID 6126289. doi:10.2165/00003088-198207040-00002.

- ↑ Van Hoogdalem EJ, de Boer AG, Breimer DD (1991). "Pharmacokinetics of rectal drug administration, Part 1". Clin Pharmakokinet. 21 (1): 11–26. doi:10.2165/00003088-199121010-00002.

- ↑ Van Hoogdalem EJ, de Boer AG, Breimer DD (1991). "Pharmacokinetics of rectal drug administration, Part 2". Clin Pharmakokinet. 21 (2): 110–128. doi:10.2165/00003088-199121020-00003.

- ↑ Moolenaar F, Koning B, Huizinga T (1979). "Biopharmaceutics of rectal administration of drugs in man. Absorption rate and bioavailability of phenobarbital and its sodium salt from rectal dosage forms". International Journal of Pharmacaceutics. 4 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1016/0378-5173(79)90057-7.

- ↑ Graves NM, Holmes GB, Kriel RL, Jones-Saete C, Ong B, Ehresman DJ (1989). "Relative bioavailability of rectally administered phenobarbital sodium parenteral solution". DICP, the Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 23: 565–568. doi:10.1177/1060028089023007-806.

- ↑ Moolenaar S, Bakker S, Visser J, Huizinga T (1980). "Biophamacutics of rectal administration of drugs in man IX. Comparative biopharmaceutics of diazepam after single rectal, oral, intramuscular and intravenous administration in man". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 5 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1016/0378-5173(80)90017-4.

- ↑ Nee, Douglas, Pharm D, MS. "Rectal Administration of Medications at the End of Life". HPNA Teleconference, December 6, 2006, accessed November 2013.

- ↑ Use of Rectal Meds for Palliative Care Patients. End of Life / Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin

- ↑ "injection". Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ↑ "MDMA (ecstasy) metabolites and neurotoxicity: No occurrence of MDMA neurotoxicity from metabolites when injected directly into brain, study shows". Neurotransmitter.net. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ McKeran RO, Firth G, Oliver S, Uttley D, O'Laoire S; Firth, G; Oliver, S; Uttley, D; O'Laoire, S (2010-07-06). "A potential application for the intracerebral injection of drugs entrapped within liposomes in the treatment of human cerebral gliomas". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 48 (12): 1213–1219. PMC 1028604

. PMID 2418156. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.12.1213.

. PMID 2418156. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.12.1213. - ↑ "Blood–brain barrier changes following intracerebral injection of human recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α in the rat". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 20: 17–25. doi:10.1007/BF01057957. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ "Acute Decreases in Cerebrospinal Fluid Glutathione Levels after Intracerebroventricular Morphine for Cancer Pain". Anesthesia-analgesia.org. 1999-06-22. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- 1 2 "Fenway Community Health". Fenway Health. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ Malenka, Eric J. Nestler, Steven E. Hyman, Robert C. (2009). Molecular neuropharmacology : a foundation for clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ↑ Mylonaki, I., Allémann, É., Saucy, F., Haefliger, J.-A., Delie, F., Jordan, O., 2017. Perivascular medical devices and drug delivery systems: Making the right choices. Biomaterials 128, 56-68

- ↑ "Vancocin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Sep 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Administration of Medicines". Nursing Practice Clinical Zones: Prescribing. NursingTimes.net. 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "DDS Medication Administration Recertification Manual" (PDF). DDS Recertification Review Manual. State of Connecticut Department of Developmental Services. 2006. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Quinn DI Wodak A Day RO (1997). "Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Principles of Illicit Drug Use and Treatment of Illicit Drug Users". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. Springer. 33 (5): 344–400. PMID 9391747. doi:10.2165/00003088-199733050-00003.

- ↑ http://www.ismp.org/Tools/errorproneabbreviations.pdf

- ↑ "Routes for Drug Administration" (PDF). Emergency Treatment Guidelines Appendix. Manitoba Health. 2003. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ↑ Stahl SM, Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008

- ↑ Smeltzer SC Bare BG, Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing, 9th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2000

- ↑ Lavik, E. and R. Langer, Tissue engineering; current state and perspectives. Applied Microbiology Biotechnology, 2004. 65: p. 1-8

External links

- The 10th US-Japan Symposium on Drug Delivery Systems

- FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Data Standards Manual: Route of Administration.

- FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Data Standards Manual: Dosage Form.

- A.S.P.E.N. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- Drug Administration Routes at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

-solution.jpg)