Drepanosaur

| Drepanosaurs Temporal range: Late Triassic, 220–216.5 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

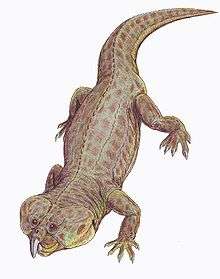

| Fossil specimen of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Protorosauria |

| Clade: | †Drepanosauromorpha Renesto et al., 2010 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Drepanosaurs (members of the clade Drepanosauromorpha) are a group of strange reptiles that lived during the Carnian stage of the late Triassic Period, between 220 and 216 million years ago.[1] The various species of drepanosaurid were characterized by odd specialized grasping limbs and often prehensile tails, adaptions for arboreal (tree-dwelling) and/or possibly aquatic lifestyles. Fossils of drepanosaurs have been found in Arizona, New Mexico, New Jersey, Utah, England, and northern Italy. The name is taken from the family's namesake genus Drepanosaurus, which means "sickle lizard", a reference to their strongly curved claws.

Description

Drepanosaurs are notable for their distinctive, triangular skulls, which resemble the skulls of birds. Some drepanosaurs, such as Hypuronector, had pointed, toothless, bird-like beaks. This similarity to birds may have led to the possible mis-attribution of a drepanosaur skull to the would-be "first bird", Protoavis.[2]

Drepanosaurs featured a suite of bizarre, almost chameleon-like skeletal features. Above the shoulders of most species was a specialized "hump" formed from fusion of the vertebrae, possibly used for advanced muscle attachments to the neck, and allowing for quick forward-striking movement of the head (perhaps to catch insects). Many had derived hands with two fingers opposed to the remaining three, an adaptation for grasping branches. Some individuals of Megalancosaurus (possibly exclusive to either males or females) had a primate-like opposable toe on each foot, perhaps used by one sex for extra grip during mating. Most species had broad, prehensile tails, sometimes tipped with a large "claw", again to aid in climbing. These tails, tall and flat like those of newts and crocodiles, have led some researches to conclude that they were aquatic rather than arboreal. In 2004, Senter dismissed this idea, while Colbert and Olsen, in their description of Hypuronector, state that while other drepanosaurs were probably arboreal, Hypuronector was uniquely adapted to aquatic life.[3] The tail of this genus was extremely deep and non-prehensile – much more fin-like than members of the more exclusive group Drepanosauridae.[4]

Aerial locomotion has been attributed to at least two drepanosaur genera: Megalancosaurus and Hypuronector. The first was originally suggested by Ruben et al 1998 on the basis of bird-like characters and limb proportions,[5] but while not ruled out entirely they have since been largely dismissed, due to the animal's more clunky, chameleon-like anatomy.[6] The latter, however, is much more likely a glider or flyer, due to the elongated forelimbs.[7]

Classification

Drepanosaurs have been difficult to pin down in terms of their phylogenetic position. They have been assigned by some researches to the prolacertiformes, though more recent studies place them together with the coelurosauravids and Longisquama in a clade called the Avicephala (in Senter's analysis nested within Diapsida but outside Neodiapsida, defined by Senter as the clade containing "all taxa phylogenetically bracketed by Younginiformes and living diapsids").[3][8]

Within Avicephala, Senter named the group Simiosauria ("monkey lizards") for the extremely derived tree-dwelling forms. Simiosauria was defined as "all taxa more closely related to Drepanosauridae than to Coelurosauravus or Sauria." However, Renesto and colleagues (see below) found drepanosaurids to lie within Sauria, which would make the clade Simiosauria obsolete. Senter found that Hypuronector, originally described as a drepanosaurid, actually lies just outside that clade, along with the primitive drepanosaur Vallesaurus. He also recovered a close relationship between the drepanosaurids Dolabrosaurus and Megalancosaurus.[3]

The following cladogram was found by Senter in his 2004 analysis.[3]

| Simiosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

A clade containing drepanosaurids, Longisquama and Coelurosauravus (as well as Wapitisaurus) was also recovered in an earlier analysis conducted by John Merck (2003); however, in Merck's analysis this clade was nested within Neodiapsida, as the sister taxon of Sauria.[9] Drepanosaurids were also found to be non-saurian neodiapsids in an analysis conducted by Johannes Müller (2004); however, in this analysis Drepanosauridae were not found to be closely related to Coelurosauravus, but rather they were recovered as the sister taxon of Kuehneosauridae.[10]

Renesto and Binelli (2006) found that when pterosaur Eudimorphodon was added to Senter's (2004) original matrix it was found to be a member of Senter's Avicephala. The authors also conducted a second analysis, this time based on a character set and matrix updated by scoring additional characters previously reported as unknown and by adding a few relevant characters. This analysis recovered drepanosaurids as the sister taxon of Eudimorphodon; the clade containing pterosaurs and drepanosaurids was recovered as the sister taxon of Archosauriformes. Longisquama and Coelurosauravus were not found to be closely related to drepanosaurids, but instead were recovered as non-neodiapsid diapsid as in Senter's (2004) analysis. However, according to Renesto and Binelli it is feasible that this might be a result of poor knowledge of Longisquama rather than a reflection of its true phylogenetic position. The authors did note that there are similarities in the structure of forelimb and shoulder region of Longisquama and all or some drepanosaurids (e.g. both Longisquama and Vallesaurus have the fourth digit of manus as long as humerus); they stressed that they could not rule out that at least some of the similarities are convergent due to similar mode of life, and that they did not examine Longisquama firsthand, but stated that further studies of drepanosaurids should take the hypothesis that Longisquama might be a drepanosaurid into consideration.[11]

In a later study Renesto et al. (2010)[12] demonstrated that Senter (2004) cladogram was based on poorly defined characters and dataset. The resulting phylogeny was therefore very unusual compared to any other previous study on drepanosaurs or related taxa. The new cladogram proposed in this last study abandoned both Avicephala (because it is polyphyletic) and Simiosauria. Senter's definition of Simiosauria included Sauria as an external specifier, causing the clade to become obsolete in Renesto et al.'s study (where drepanosaurs nested within Sauria). Renesto and colleagues instead defined a new clade, Drepanosauromorpha, as the least inclusive clade containing Hypuronector limnaios and Megalancosaurus pronenesis. Another more inclusive taxon, Elyurosauria ("lizard with coiled tails"), was erected, in order to include all the drepanosaurs with coiled tails, Vallesaurus is thus more derived than Hypuronector (as clearly shown by its morphology). Drepanosaurus and Megalancosaurus are also in a new taxon named Megalancosaurinae.

The alternative cladogram presented in Renesto et al. (2010).[12]

| Drepanosauromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Renesto et al. (2010) used modified versions of the matrices from the analyses of Laurin (1991)[13] and Dilkes (1998)[14] in order to determine the phylogenetic position of Drepanosauromorpha within Diapsida. The analyses using Laurin's (1991) matrix recovered drepanosaurs either as the sister group of the clade containing Prolacerta, Trilophosaurus and Hyperodapedon, i.e. Archosauromorpha, or in unresolved polytomy with Archosauromorpha and Lepidosauromorpha. The analyses using Dilkes's (1998) matrix recovered drepanosaurs either as protorosaur archosauromorphs and the sister taxon to the clade containing Tanystropheus, Langobardisaurus and Macrocnemus, or in unresolved polytomy with Lepidosauromorpha, Choristodera and several archosauromorph clades. Renesto et al. (2010) concluded that avicephalan synapomorphies proposed by Senter (2004) are merely evolutionary convergences caused by common lifestyle shared by drepanosaurids, coelurosauravids and Longisquama. The authors did not rule out the possibility that drepanosaurs and Longisquama might really be close relatives, but stated that additional data about Longisquama needs to be reported to test that.[12]

Gottmann-Quesada and Sander (2009) included one member of Drepanosauridae, Megalancosaurus, in their analysis of archosauromorph relationships; it was found to be one of the basalmost known members of Archosauromorpha and the sister taxon of Protorosaurus.[15]

In a different 2009 study Susan E. Evans conducted a phylogenetic analysis using a modified version of Müller's (2004) matrix. Evans recovered Drepanosauridae as the sister taxon of the clade containing basal kuehneosaurid Pamelina and the rest of Kuehneosauridae; however, unlike in Müller's analysis, drepanosaurids and kuehneosaurids were recovered as non-lepidosaurian lepidosauromorphs. Evans did note that the two families share few synapomorphies, with Müller (2004) citing only two. One of them is the increased angulation of the zygapophyses in the posterior dorsal vertebrae; Evans noted that this character is also present in the skeletons of lizards belonging to the genus Draco, "and is likely to be functional (and thus potentially convergent)". The other one, the enclosed thyroid fenestra in the pelvis, "may be variable in the British kuehneosaurs and remains unknown in Pamelina", according to Evans. The author also noted that there are many differences between the skull of drepanosaurids and kuehneosaurids, and that the only skull characters shared by members of both families are primitive neodiapsid characters.[16]

References

- ↑ Renesto, S., Spielmann, J.A., and Lucas, S.G. (2009). "The oldest record of drepanosaurids (Reptilia, Diapsida) from the Late Triassic (Adamanian Placerias Quarry, Arizona, USA) and the stratigraphic range of the Drepanosauridae." Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen, 252(3): 315-325. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2009/0252-0315.

- ↑ Renesto, S. (2000). "Bird-like head on a chameleon body: new specimens of the enigmatic diapsid reptile Megalancosaurus from the Late Triassic of northern Italy." Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 106: 157–180. Abstract

- 1 2 3 4 Senter, P. (2004). "Phylogeny of Drepanosauridae (Reptilia: Diapsida)." Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2(3): 257-268.

- ↑ Colbert, E. H., and Olsen, P. E. (2001). "A new and unusual aquatic reptile from the Lockatong Formation of New Jersey (Late Triassic, Newark Supergroup)." American Museum Novitates, 3334: 1-24.

- ↑ Ruben, R. R. (1998). Gliding adaptations in the Triassic archosaur Megalancosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 18 (3), 73A.

- ↑ Renesto, S. (2000). Bird-like head on a chameleon body: new specimens of the enigmatic diapsid reptile Megalancosaurus from the Late Triassic of Northern Italy. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research In Paleontology and Stratigraphy), 106(2).

- ↑ Renesto, S., Spielmann, J. A., Lucas, S. G., & Spagnoli, G. T. (2010). The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha): Bulletin 46 (Vol. 46). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

- ↑ Renesto, S. (1994). "Megalancosaurus, a possibly arboreal archosauromorph (Reptilia) from the Upper Triassic of northern Italy." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14(1): 38-52.

- ↑ Merck, John (2003). "An arboreal radiation of non-saurian diapsids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (Supplement to 3): 78A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2003.10010538.

- ↑ Müller, Johannes (2004). "The relationships among diapsid reptiles and the influence of taxon selection". In Arratia, G; Wilson, M.V.H.; Cloutier, R. Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 379–408. ISBN 978-3-89937-052-2.

- ↑ Silvio Renesto; Giorgio Binelli (2006). "Vallesaurus cenensis Wild, 1991, a drepanosaurid (Reptilia, Diapsida) from the Late Triassic of northern Italy" (PDF). Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 112 (1): 77–94.

- 1 2 3 Silvio Renesto, Justin A. Spielmann, Spencer G. Lucas, and Giorgio Tarditi Spagnoli. (2010). The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 46:1–81

- ↑ Michel Laurin (1991). "The osteology of a Lower Permian eosuchian from Texas and a review of diapsid phytogeny". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 101 (1): 59–95. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1991.tb00886.x.

- ↑ David M. Dilkes (1998). "The Early Triassic rhynchosaur Mesosuchus browni and the interrelationships of basal archosauromorph reptiles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 353 (1368): 501–541. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0225.

- ↑ Annalisa Gottmann-Quesada; P.Martin Sander (2009). "A redescription of the early archosauromorph Protorosaurus speneri MEYER, 1832, and its phylogenetic relationships". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 287 (4-6): 123–220. doi:10.1127/pala/287/2009/123.

- ↑ Susan E. Evans (2009). "An early kuehneosaurid reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 65: 145–178.

External links

- Monkey Lizards of the Triassic - An illustrated article on drepanosaurs from HMNH.

- Prof. Silvio Renesto—Vertebrate Paleontology at Insubria University: Research - Images and discussion of Drepanosaurus.

- Prof. Silvio Renesto—Vertebrate Paleontology at Insubria University: Research - Images and discussion of Megalancosaurus.