Dost Mohammad of Bhopal

| Dost Mohammad Khan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nawab of Bhopal | |

| Reign | 1707-1728 |

| Predecessor | None (Position Established) |

| Successor | Sultan Muhammad Khan (with Yar Mohammad Khan as regent) |

| Born |

1657 Tirah, Mughal Empire (Now Pakistan) |

| Died |

1728 Bhopal, Bhopal |

| Burial |

Fatehgarh, Bhopal 23°15′N 77°25′E / 23.25°N 77.42°ECoordinates: 23°15′N 77°25′E / 23.25°N 77.42°E |

| Consort |

Mehraj Bibi Fatah Bibi Taj Bibi |

| Pashto name | دوست محمد خان ميرازي خېل |

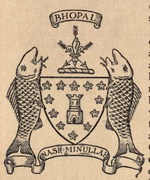

| Dynasty | Mirazi khel of Orakzai tribe |

| Father | Nur Mohammad Khan |

| Religion | Islam |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Nawab of Bhopal |

| Rank | Sowar, Faujdar, Subadar |

| Battles/wars | Mughal-Maratha Wars |

Dost Mohammad Khan (c. 1657–1728) was the founder of the Bhopal State in central India.[1] He founded the modern city of Bhopal, the capital of the Madhya Pradesh state.[2]

A Pashtun[3][4] from Tirah, Dost Mohammad Khan joined the Mughal imperial army at Delhi in 1703. He rapidly rose through the ranks, and was assigned to the Malwa province in central India. After the death of the emperor Aurangzeb, Khan started providing mercenary services to several local chieftains in the politically unstable Malwa region. In 1709, he took on the lease of Berasia estate, while serving the small Rajput principality of Mangalgarh as a mercenary. He invited his Pashtun kinsmen to Malwa to create a group of loyal associates.[5] Khan successfully protected Mangalgarh from its other Rajput neighbors, married into its royal family, and took over the state after the death of its heirless dowager Rani.[6]

Khan sided with the local Rajput chiefs of Malwa in a rebellion against the Mughal empire. Defeated and wounded in the ensuing battle, he ended up helping an injured Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan Barha, one of the Sayyid Brothers. This helped him gain the friendship of the Sayyid Brothers, who had become highly influential king-makers in the Mughal court. Subsequently, Khan annexed several territories in Malwa to his state. Khan also provided mercenary services to the Rani Kamlapati, the ruler of a small Gond kingdom, and received the territory of Bhopal (then a small village) in lieu of payment. After the Rani's death, he killed her son and annexed the Gond kingdom.[7] During the early 1720s, he transformed the village of Bhopal into a fortified city, and claimed the title of Nawab, which was used by the Muslim rulers of princely states in India.[8]

Khan's support to the Sayyid Brothers earned him the enmity of the rival Mughal nobleman Nizam-ul-Mulk. The Nizam invaded Bhopal in March 1724, forcing Khan to cede much of his territory, give away his son as hostage and accept the Nizam's suzerainty.[5] In his final years, Khan sought inspiration from Sufi mystics and saints, veering towards spiritualism. He and the other Pathans who settled in Bhopal during his reign, brought the Pathan and Islamic influence to the culture and architecture of Bhopal.

At its zenith, the Bhopal state comprised a territory of around 7,000 square miles (18,000 km2).[9] The state became a British protectorate in 1818, and was ruled by the descendents of Dost Mohammad Khan till 1949, when it was merged with the Dominion of India.

Early life

Dost Mohammad Khan was born in the Tirah region on the western frontier of the Mughal Empire (now in Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pakistan).[10] His father Nur Mohammad Khan was a Pashtun nobleman belonging to the Mirazikhel clan of the Orakzai tribe.[11] This tribe lives in Tirah and the Peshawar region.

In his mid-20s, Dost Mohammad Khan was engaged to Mehraj Bibi, an attractive girl from a neighboring Orakzai clan. However, Mehraj was later betrothed to his cousin, because Khan's character was seen as too aggressive and rough. An angry Khan killed his cousin, leading to his ostracism from his family.[9]

Attracted by the promise of a bright future in the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb's service, Khan set out for Jalalabad, near Delhi, where his Pashtun relatives had settled. He was welcomed by the family of his relative Jalal Khan, the Mughal mansabdar (a military aristocrat) of Jalalabad's suburb Lohari.[12] He arrived in Jalalabad sometime between 1696 and 1703, and spent some time with Jalal Khan's family. During a birthday celebration, a fight broke out between Dost and one of Jalal Khan's sons, over one of the young housemaids. Jalal Khan's son attacked Dost with a bow and arrow, and Dost killed him with a dagger in retaliation.[9]

Following this incident, Dost Mohammad Khan decided to flee to Delhi, the Mughal capital. His horse collapsed and died after six hours of galloping. Khan continued his journey on foot and reached Karnal.[13] While waiting in front of a bakery to steal some food, he was recognized by the old clergyman Mullah Jamali of Kashgar, who had taught him Koran in Tirah. Mullah Jamali had left Pushtunistan, and had founded a madrasa (Muslim school) in Delhi. Khan spent around a year in Delhi under Mullah Jamali's shelter, after which he decided to join the Mughal army. The Mullah helped him financially by giving him a horse and five asharfis (gold coins).[9]

Mughal military service

In 1703, Dost Mohammad Khan enlisted with Mir Fazlullah, Aurangzeb's Keeper of Arms.[13] Around 1704, he was ordered to quell a rebellion by the governor Tardi Beg, who commanded a sizable force in the Bundelkhand region. Khan led the Mughal regiment of Gwalior in a battle with the Tardi Beg's forces headed by General Kashko Khan. Although injured by the swords of Kashko Khan's guards and a mahawat (elephant rider), Khan managed to kill Kashko Khan in the battle. He delivered Kashko's decapitated head to Mir Fazlullah in Delhi.[9]

In 1705, Mir Fazlullah presented Dost Mohammad Khan's regiment to the emperor Aurangzeb. According to the Khan's rozanmacha (daily diary), Aurangzeb was impressed by him, presented him with two fistful of gold coins, and asked Fazlullah to treat him well and give him an appropriate command.[9] In return, Khan conveyed his loyalty to the Emperor. Following this, Khan rose rapidly through the ranks, and was assigned to the Malwa province in central India. Malwa was politically unstable at the time, and Aurangzeb had been replacing the governors in rapid succession. The Marathas, the Rajput chieftains and Muslim feudal chiefs were agitating for power in and around the region, and the Mughals were facing several revolts.

News of the death of Emperor Aurangzeb on 20 February 1707 reached Khan, when he was at Bhilsa. A war of succession broke out between Aurangzeb's sons, two of whom approached Khan for allegiance. However, Khan refused to side with either of them, saying that he could not raise his sword against any of his sons since he had taken an oath of being loyal to the late Emperor.[9]

Mercenary career

Following the death of the emperor Aurangzeb, Malwa started witnessing power struggles between the various chieftains in the area due to lack of a central authority. Dost Mohammad Khan became the leader of a band of around 50 Pathan mercenaries, and started providing the local chieftains protection against pillage and strife. These chieftains included the Raja Reshb Das (1695–1748) of Sitamau, Mohammad Farooq (Governor of Bhilsa), Diye Bahadur (the Mughal Deputy Governor of Malwa) and Raja Anand Singh Solanki of Mangalgarh.[14]

Mangalgarh was a small Rajput principality in Malwa, ruled by Raja Anand Singh Solanki. The dowager mother of the Raja had taken a great liking to Dost Mohammad Khan. After the Rajas's death at Delhi, she appointed him the kamdar or mukhtar ("guardian") of Mangalgarh, around 1708.[15] Khan was tasked with protecting the dowager Rani (queen) and her estate. During his service at Mangalgarh, he married Kunwar Sardar Bai, the daughter of Anand Singh,[16] who later converted to Islam and adopted the name Fatah Bibi (also spelled Fateh Bibi). Khan married several other women, but Fatah Bibi remained his favorite wife.[9]

Over the next few years, Khan operated out of Mangalgarh, working for anyone willing to pay for his reputed mercenary services.

Berasia estate

In 1709, Dost Mohammad Khan decided to build a feudal estate of his own. Berasia, a small mustajiri (rented estate) near Mangalgarh, was under the authority of the Delhi-based Mughal fief-holder Taj Mohammad Khan. It suffered from anarchy and lawlessness due to regular attacks from highwaymen and plunderers. On advice of Mohammed Sala, Sunder Rai and Alam Chand Kanoongo, Dost Mohammad Khan took on the lease of Berasia.[17] The lease involved an annual payment of 30,000 rupees, which he was able to pay with help of his wife Fatah Bibi, who belonged to the Mangalgarh royal family. Khan appointed Maulvi Mohammad Saleh as the qazi (judge), built a mosque and a fort, and installed his loyal Afghan lieutenants in various administrative capacities.[9]

Dost Mohammad Khan also tried to gain some territories in Gujarat, but was unsuccessful.[13] After being defeated by a Maratha warlord during an unsuccessful raid in Gujarat, he was imprisoned by his own rebel soldiers. He was freed after his wife Fatah Bibi paid a ransom to his captors.[9]

The rampant power struggles and disloyalty, especially his imprisonment by his own men after the Gujarat raid, had made Khan distrustful of people around him. He, therefore, invited his kinsmen in Tirah to Malwa. Khan's father, Mehraj Bibi (his wife – the girl he was engaged to in Tirah) and his five brothers arrived in Berasia in 1712, with around 50 tribesmen of the Mirazikhel. His father died in 1715, shortly after arriving in Berasia. His five brothers were Sher, Alif, Shah, Mir Ahmad and Aqil; all except Aqil died in subsequent battles. The Pashtuns who had accompanied Khan's immediate family, later came to be known as "Barru-kat Pathans", and their families became highly influential in Bhopal.[10] They were known as the Barru-kat ("reed cutter") Pathans since they initially made their homes with thatched reeds.

Struggles with the local chieftains

The Rajput neighbors of Mangalgarh, led by the Thakur (chief) of Parason, formed an alliance to counter the growing power of the Rani of Mangalgarh. The ensuing battle between Mangalgarh and the Thakur went on for days. During the festival of Holi, the Thakur insisted on a truce for celebrations. Dost Mohammad Khan agreed to the ceasefire, but also sent a spy dressed as a beggar to the Thakur's camp. The spy came back with the news that the Rajputs were in a state of drunken revelry. Khan violated the truce and raided the enemy camp at night, defeating the Rajput chieftains decisively.[12] Dost also conquered the other adjoining Rajput territories such as Khichiwara and Umatwara.[18]

In 1715, Khan ran into conflict with another neighboring Rajput chief, Narsingh Rao Chauhan (also known as Narsingh Deora), who owned the fortified village of Jagdishpur near Berasia.[19] Narsingh Deora demanded tribute from the Patel of Barkhera in Dillod, who had earlier given shelter to Dost after he fled away from the Mughal camp.[20] Khan agreed to negotiate a treaty with Narsingh, and the two parties met at Jagdishpur, with 16 men on each side. Khan pitched a tent on the banks of Thal river (also known as Banganga) for the meeting. After a lunch arranged by him for both the parties, he stepped outside on the pretext of ordering ittar (perfume) and paan (betel leaf), which was actually a signal for Khan's hiding men to kill the Rajputs.[12] It is said that the Thal river appeared red with the blood of the victims, and therefore was renamed to "Halali" river (the river of slaughter).[6] After this incident, Khan renamed Jagdishpur to Islamnagar, strengthened the fort and made the place his headquarters.

Khan's cousin Diler Mohammad Khan (or Dalel Khan) had also acquired some territory, establishing the Kurwai State. In 1722, he visited Berasia with a proposal that the two cousins join hands in extending their territory, and their acquisitions of land and property be equally divided. However, Dost Mohammad Khan got his cousin murdered.[13]

Dost Mohammad Khan also fought against Diye Bahadur, a Rajput general and Mughal subedar (governor). Diye Bahadur's forces initially defeated Khan's army, which fled from the battlefield. A badly wounded Khan, who had lost one of his brothers in the battle, was taken prisoner. He was well-treated by the Rajputs, and was presented before Diye Bahadur after recuperating from his wounds. Diye Bahadur offered Khan a position in his own forces, but Khan declined, while expressing gratitude for Bahadur's kindness. When asked what he would do if set free, Khan replied that he will wage another battle against Diye Bahadur. Bahadur, impressed by the Khan's bravery, released him. A few months later, Khan defeated Diye Bahadur with his newly raised force.[9]

Allegiance to the Sayyid Brothers

The Sayyid Brothers were two nobles, who had become highly influential in the Mughal Court after the emperor Aurangzeb's death. Aurangzeb's son Bahadur Shah I defeated his brothers to capture the throne with the help of Sayyid Brothers and Nizam-ul-Mulk, another influential administrator in the Mughal court. Bahadur Shah I died in 1712 and his successor Jahandar Shah was assassinated on the orders of the Sayyid Brothers.[21] In 1713, Jahandar's nephew Farrukhsiyar was installed as a puppet king by the Brothers, who conspired to send Nizam-ul-Mulk to the Deccan, away from the Mughal Court. Disillusioned with the Mughal court, Nizam-ul-Mulk also intended set up his own independed state, and left for the South as the Governor of Malwa and Deccan.

When the Mughals sent a force from Delhi to curb the rebellion by the Rajput chiefs of Malwa, Dost Mohammad Khan sided with the Rajputs. In the resulting battle, his men fled from the battlefield, leaving him badly wounded and unconscious. In his diary, Khan wrote that he regained consciousness only when jackals began nibbling his limbs. Khan offered the little water remaining in his mushuk (water carrier) to an injured and thirsty Mughal soldier, who was moaning to ward off the jackals. This man was Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan Barha, the younger of the Sayyid Brothers.[9]

When the Mughal soldiers arrived to rescue Sayyid Hussain Ali, Dost Mohammad Khan was also rescued as a reward for his kindness in offering water to the injured Mughal nobleman. Khan subsequently recuperated under the care of Sayyaid Hussain Ali, who offered to make him the Governor of Allahabad. Khan declared his loyalty to the Sayyid Brothers, but refused the offer, because he did not want to leave Malwa. He was sent back to Mangalgarh with gifts of gold coins, a sword and a band of horses.[9]

Khan's closeness to the Sayyid Brothers later earned him the ire of Nizam-ul-Mulk, who sided with the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah to get the Sayyid Brothers killed during 1722-24.

Expansion of fiefdom

Shortly after Dost Mohammad Khan's return to Mangalgarh, the dowager Rani (queen) of the principality died heirless. Following the Rani's death, Khan usurped the Mangalgarh territory.[22] Supported by his loyal "Barru-kat" Pathan associates, Khan set to carve out a fiefdom of his own. He waged battles to annex several territories, losing two of his brothers in the fights. Several local chieftains (jagirdars and zamindars) accepted his suzerainty without putting up a fight.

While Khan was away from Mangalgarh, Mohammad Farooq Hakim, the Governor of Bhilsa, imprisoned his men and confiscated his personal property. When Khan returned and confronted him, he said that he believed that Khan had died in the battle with the Mughals. He released the imprisoned men, but returned only half of the Khan's belongings. The resulting hostility eventually led to a battle near Bhilsa. Farooq's army included 40,000 Maratha and Rajput soldiers, while Khan commanded just 5000 Afghans, supported by some Rajput soldiers. In a one-sided battle, Khan lost his brother Sher Mohammed Khan, and his men fled from the battlefield. Dost Mohammad Khan, with some of his most loyal men, had to hide in a thicket near the battlefield.[15] As he lay hidden, he saw Farooq riding an elephant in the victory procession. He dressed himself in the uniform of one of Farooq's slain soldiers, hiding his face with a scarf and a helmet. Amid the din of the victory drums, he mounted the howdah (seat) on the elephant, killed Farooq and his guard, and claimed victory.[23]

Khan also seized control of several territories in Ashta, Debipura, Doraha, Gulgaon, Gyaraspur, Ichhawar, Sehore and Shujalpur.[8][24]

Rani Kamlapati

In the 1710s, the area around the upper lake of Bhopal was mainly populated by the Bhil and the Gond tribals. Nizam Shah, the strongest of the local Gond warlords, ruled his territory from the Ginnor fort (Ginnorgarh in the present-day Sehore district). Ginnor was considered an impregnable fort, located at the summit of a steep 2000-foot-high rock, and surrounded by thick forest. Rani Kamlapati (or Kamlavati), the daughter of Chaudhari Kirpa-Ramchandar, was one of the seven wives of Nizam Shah. She was famous for her beauty and talents: the local legends describe her as more beautiful than a pari (fairy).[9]

Nizam Shah was poisoned to death by his nephew Alam Shah (also known as Chain Shah), the raja of Chainpur-Bari, who wanted to marry Kamlapati.[7] Kamlapati offered Dost Mohammad Khan a hundred thousand rupees to protect her honor and her kingdom, and to avenge her husband's death. Khan accepted the offer, and Kamlapati tied a rakhi on his wrist (traditionally tied by a sister on her brother's hand). Khan led a joint army of Afghan and Gond soldiers to defeat and kill Alam Shah. The slain king's territory was annexed to Kamlapati's kingdom. The Rani did not have one hundred thousand rupees, so she paid him half the sum and gave the village of Bhopal in lieu of the remainder. Khan was also appointed the manager of Kamlapati's state, and virtually became a ruler of the small Gond kingdom.[20] Khan remained loyal to the Rani and her son Nawal Shah till her death. Historians have debated the reason for Khan's loyalty: some say he was enchanted with Kamlapati's charm and beauty; others think that he believed in keeping his word to women (he had been loyal to the Rani of Mangalgarh till her death as well).[9] In Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan, James Tod mentions a folk story that describes how the "Queen of Ganore" killed Khan with a poison dress, when he asked her to marry him.[25][26]

In 1723, Rani Kamlapati committed suicide near her palace (present-day Kamla Park in Bhopal). Dost initially feigned allegiance to the Rani's son Nawal Shah, who controlled the Ginnor fort, and was invited to live in the fort. Khan disguised 100 of his soldiers as women, and sent them to Ginnor in dolis that were supposed to contain his wife and family. The unsuspecting guards of Nawal Shah let the dolis inside the fort without examination. At night, Khan's soldiers killed Nawal Shah and his guards.[16] Khan then took the control of Ginnor fort and other territories of Kamlapati's kingdom.

Development of Bhopal

Dost Mohammad Khan ruled his state from his capital at Islamnagar. At the time of Kamlapati's death, Bhopal was a village of about 1000 people, to the south of Islamnagar. One day, during a shikar (hunting) trip, Dost Mohammad Khan and his wife Fatah Bibi decided to rest in the Bhopal village. Dost fell asleep, and dreamt that an old saint had asked him to build a fort.[9] He told his wife about the dream, who asked him to construct a fort at the spot. This resulted in construction of Fatehgarh fort, named after Fatah Bibi. The foundation of the fort was laid on 30 August 1723.[14] The first stone was laid by Qazi Mohammad Moazzam of Raisen, who later became the qazi (Islamic judge) of Bhopal.[6] The fort was eventually expanded to encircle the village of Bhopal. It never fell to an enemy, and as late as 1880, the city was mainly confined to this fort.

The first mosque of Bhopal, the Dhai Seedi Ki Masjid, was also built during this time, so that the fort guards could perform namaaz (prayers). A handwritten copy of the Quran with a Persian language translation was also kept at the fort – the book had pages of size 5x2.5 feet (this copy was later given to the Al-Azhar University by Khan's descendant Nawab Hamidullah).[9] Dost Mohammad Khan and his family gradually started using Bhopal as their main bastion, though Islamnagar still remained the official capital of his state.

During 1720-1726, Dost started surrounding the city with a protective wall. Thus, Bhopal was transformed from a village to a fortified town with six gates:[7]

- Ginnori (the gate leading to Ginnorgarh)

- Budhwara (Wednesday gate)

- Itwara (Sunday gate)

- Jumerati (Thursday gate)

- Peer (Monday gate)

- Imami (used for Tazia possession on the day of Muharram)

Bijay Ram (or Bijjeh Ram), the Rajput chieftain of Shujalpur, was made the dewan (chief minister) of the Dost's state. Being a Hindu, he helped Dost win over the local population.[13]

Conflict with the Asaf Jah I

By the early 1720s, Dost Mohammad Khan had transferred himself from a mercenary to the ruler of a small state. After the death of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, the Malwa territory was claimed by the Marathas and some kings of Rajputana, in addition to the Mughals. All these powers made such claims mainly through proxies (such as the local chieftains), although they did engage in occasional punitive raids when the local chiefs refused to pay the tribute demanded by them. Dost Mohammad Khan acknowledged Mughal authority by sending expensive gifts (such as an elephant) and flattering letters to the Mughal Emperor, who was controlled by the Sayyid Brothers. Emperor Farrukhsiyar conferred on him the title Nawab Diler Jung, probably on the recommendation of the Sayyid Brothers.[9] Dost also prevented the Maratha invasions by regularly paying them chauth (tribute).[27]

In 1719, the Sayyid Brothers murdered Emperor Farrukhsiyar, who had been plotting against them. Subsequently, they placed Rafi Ul-Darjat and Rafi ud-Daulah as the emperors, both of whom died of sickness in 1719.[28] Muhammad Shah then ascended the Mughal throne with the help of the Sayyid Brothers, who acted as his regents till 1722. The hostility between Sayyid Brothers and the rival nobleman Nizam-ul-Mulk had been growing in the recent years. Dost Mohammad Khan was well-aware of the power of Nizam-ul-Mulk, who was the Subahdar (Governor) of Malwa; he had seen his strong force passing through Bhopal on its way to the Deccan in the south. However, he allied himself with the Mughal Court controlled by the Sayyid Brothers, with whom he had developed a close friendship.[9]

In 1720, the Sayyid Brothers dispatched a Mughal force led by Dilawar Ali Khan against Nizam in Malwa. When Dost Mohammad Khan was asked to support this force, he sent a contingent commanded by his brother Mir Ahmad Khan to fight on the Mughal side. The Mughal force ambushed the Nizam at Burhanpur near Khandwa on 19 June 1720, but was decisively defeated by the Nizam, who was supported by the Marathas. Dilawar Khan, Mir Ahmad and other generals sent by the Sayyid Brothers were killed in the battle, and Dost Mohammad Khan's forces retreated to Malwa, pursued and plundered by the Nizam's Maratha auxiliaries.[29] Thus, Dost earned the wrath of both the Nizam and the Maratha Peshwa for opposing them.

Subsequently, Nizam-ul-Mulk helped the emperor Muhammad Shah in getting the Sayyid Brothers killed.[30] After having established control over the Deccan, he decided to get even with Dost Mohammad Khan for supporting the Sayyid Brothers.[18] On 23 March 1723, he despatched a force to Bhopal, where Khan put up some fight from his fort.[31] After a brief siege, Khan agreed to a truce the next day. He arranged an expensive welcome banquet for the Nizam, presented him with an elephant and stationed his forces on a hillock renamed to Nizam tekri (Nizam's hillock) in the Nizam's honor. He agreed to cede part of his territory, including the Islamnagar fort. He also paid a tribute of ten lakh (one million) rupees with a promise to pay a second installment later. He was also forced to send his 14-year-old son and heir Yar Mohammad Khan to Nizam's capital Hyderabad, as a hostage.[13]

The Nizam assumed control over Bhopal, and appointed Dost Mohammad Khan as a kiledar (fort commander). In return for a fort, the payment of Rs. 50,000 and the pledge of 2000 troops, the Nizam granted a sanad (decree) to Khan recognizing the latter's right to collect the revenues from the territory.[32]

Death and legacy

In his final years, which saw his humiliation at the hands of the Nizam, Khan's aggression had mellowed down considerably. He sought inspiration from Sufi mystics and saints, and veered towards spiritualism. He admonished his brother Aqil for desecrating a Buddhist statue in Sanchi. He encouraged several scholars, hakeems (doctors) and artists to settle in Bhopal. Several Pashtuns, including those of Yusufzai, Rohilla and Feroze clans, settled in Bhopal during his reign due to relatively peaceful environment of the area.[13]

.jpg) Mausoleum of Dost Khan and Fateh Bibi Information

Mausoleum of Dost Khan and Fateh Bibi Information Mausoleum of Dost Khan at Bhopal

Mausoleum of Dost Khan at Bhopal.jpg) Mausoleum of Dost Khan

Mausoleum of Dost Khan

Dost Mohammad Khan died of an illness in March 1728. It is said that he had 30 wounds on his body from the various fights and battles he had participated in.[5] He was buried in the Fatehgarh Fort beside his wife Fatah Bibi.

Dost Mohammad Khan was survived by 5 daughters and 6 sons (Yar, Sultan, Sadar, Fazil, Wasil and Khan Bahadur). He married several times, but only few of his wives have been chronicled. Four of his children were from his first wife Mehraj Bibi. Kunwar Sardar Bai (later Fatah Bibi), his favorite wife of Rajput descent, was childless, but had an adopted son called Ibrahmin Khan. Khan had three children from Jai Kunwar (later Taj Bibi), who had been presented to him by the zamindar (landowning chieftain) of Kaliakheri.[9]

The court of Bhopal appointed Khan's younger son, Sultan Mohammad, as his successor. Sultan Mohammad Khan was 7 or 8-year-old at the time. The Nizam overruled the appointment, and sent the Dost's hostage teenage son Yar Mohammad Khan to Bhopal with a thousand horsemen.[5] Yar Mohammad Khan was the eldest son of Dost, but he was not his first wife Mehraj Bibi's son; he could have been born of a consort soon after Dost came to Malwa. The court of Bhopal refused to grant him the title of Nawab on the grounds that he was an illegitimate son.[17] Yar Mohammad was, however, allowed to execute the royal functions as the regent.

The Bhopal State later became a protectorate of the British India, and was ruled by the descendents of Dost Mohammad Khan till 1949, when it was merged into the newly independent Union of India.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dost Mohammad Khan (Bhopal). |

- ↑ John Falconer; James Waterhouse (2009). The Waterhouse albums: central Indian provinces. Mapin. ISBN 978-81-89995-30-0.

- ↑ Fodor's India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, 1984. Fodor's. 1984. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-679-01013-5.

- ↑ "Bhopal". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ Waltraud Ernst, Biswamoy Pati, eds. (2007). India's princely states: people, princes and colonialism. Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (Volume 45) (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-415-41541-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 William Hough (1845). A brief history of the Bhopal principality in Central India. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press. pp. 1–4. OCLC 16902742.

- 1 2 3 Kamla Mittal (1990). History of Bhopal State. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 2. OCLC 551527788.

- 1 2 3 Jogendra Prasad Singh; Anita Dharmajog (1998). City planning in India: a study of land use of Bhopal. Mittal Publications. pp. 28–33. ISBN 978-81-7099-705-4.

- 1 2 Somerset Playne; R. V. Solomon; J. W. Bond; Arnold Wright (1922). Arnold Wright, ed. Indian states: a biographical, historical, and administrative survey (illustrated, reprint ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 57. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Shaharyar M. Khan (2000). The Begums of Bhopal (illustrated ed.). I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-1-86064-528-0.

- 1 2 Abida Sultaan (2004). Memoirs of a rebel princess (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. xli-11. ISBN 978-0-19-579958-3.

- ↑ "Mirazi" is probably of "Mir Aziz". (Shaharyar M. Khan, 2000)

- 1 2 3 Shah Jahan Begam (1876). The táj-ul ikbál tárikh Bhopal, or, The history of Bhopal. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. OCLC 28302607.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ashfaq Ali (1981). Bhopal, past and present (2nd ed.). Jai Bharat. OCLC 7946861.

- 1 2 Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Raisen. Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers (Volume 27). Government Central Press. 1979. p. 54. OCLC 58636955.

- 1 2 "Journal of Indian history". 39. Dept. of Modern Indian History, University of Allahabad. 1961: 16–19.

- 1 2 Sikandar Begam (Nawab of Bhopal) & C. B. Willoughby-Osborne (1870). A pilgrimage to Mecca. Translated by Mrs. E. L. Willoughby-Osborne. W. H. Allen. pp. 167–168. OCLC 656648636.

- 1 2 S.R. Bakshi; O.P. Ralhan (2007). Madhya Pradesh Through the Ages. Sarup & Sons. pp. 380–383. ISBN 978-81-7625-806-7.

- 1 2 Rajendra Verma (1984). The freedom struggle in the Bhopal State. Intellectual. OCLC 562460775.

- ↑ R. K. Sharma; Rahman Ali (1980). Archaeology of Bhopal region. Indian history and culture series (Volume 1). Agam Kala Prakashan. OCLC 7173802.

- 1 2 Ajai Pal Singh (1987). Forts and fortifications in India. Agam Kala Prakashan. p. 94. OCLC 16758153.

- ↑ Salma Ahmed Farooqui. A Comprehensive History of Medieval India. Pearson Education India. p. 308. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- ↑ Shyam Singh Shashi (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Volume 100. Anmol. p. 158. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- ↑ Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Vidisha. Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers (Volume 42). Government Central Press. 1979. OCLC 42872666.

- ↑ Prem Chand Malhotra (1964). Socio-economic survey of Bhopal City and Bairagarh. Asia Publishing House. p. 2. OCLC 1318920.

- ↑ James Tod (2001) [1829]. Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan (Volume 1) (2nd ed.). Asian Educational Services. pp. 536–538. ISBN 978-81-206-1289-1.

- ↑ Gillian Bennett (2009). Bodies: Sex, Violence, Disease, and Death in Contemporary Legend. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-60473-245-0.

- ↑ Zahiruddin Malik (1977). The reign of Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748. Asia Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-210-40598-7.

- ↑ Richards, John F. (1996). The Mughal Empire. New Cambridge history of India (Volume 5) (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ↑ Raghubir Sinh (1993). Malwa in Transition Or a Century of Anarchy: The First Phase, 1698-1765. Asian Educational Services. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-206-0750-7.

- ↑ Pran Nath Chopra (2003). A comprehensive history of modern India, Volume 3. Sterling. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-207-2506-5.

- ↑ William Irvine (1922). Later Mughals. Vol. 2, 1719-1739. OCLC 452940071.

- ↑ Barbara N. Ramusack (2004). The Indian princes and their states, Volume 3. New Cambridge history of India (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-26727-4.