Mechelen transit camp

| Mechelen transit camp SS-Sammellager Mecheln | |

|---|---|

| Transit camp | |

|

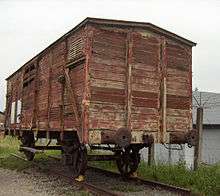

Modern view of Dossin Barracks which housed the transit camp | |

Location of the camp in Belgium | |

| Coordinates | 51°02′02″N 4°28′42″E / 51.03389°N 4.47833°ECoordinates: 51°02′02″N 4°28′42″E / 51.03389°N 4.47833°E |

| Other names | SS-Sammellager Mecheln |

| Location | Mechelen, Belgium |

| Operated by |

Nazi Germany

|

| Original use | Military barracks[Note 1] |

| First built | 1756 |

| Operational | July 1942 – September 1944 |

| Inmates | mainly Jews and Roma |

| Number of inmates |

Jews: 24,916[1] Roma: 351[2] |

| Killed | c.300[3] |

| Liberated by | Allied Forces, 4 September 1944 |

| Notable inmates | Felix Nussbaum,[4] Abraham Bueno de Mesquita |

| Website |

www |

The Mechelen transit camp, officially SS-Sammellager Mecheln in German, was a detention and deportation camp established in the former Dossin Barracks at Mechelen in German-occupied Belgium. The transit camp was run by the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo-SD),[5] a branch of the SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt, in order to collect and deport Jews and other minorities such as Romani mainly out of Belgium towards the labor camp of Heydebreck-Cosel[6] and the concentration camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau in German occupied Poland.

During the Second World War, between 4 August 1942 and 31 July 1944, 28 trains left from this Belgian casern and deported over 25,000 Jews and Roma,[1][7] most of whom arrived at the extermination camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau. At the end of war, 1240 of them had survived.[7]

Since 1996, a Holocaust museum has been open near the site of the camp: the Kazerne Dossin – Memorial.

Location

In the summer of 1942, the Nazis made preparations to deport the Jews of German-occupied Belgium, of which about 90 percent lived in the cities of Antwerp and Brussels. Mechelen, a city with a major railway hub that ensured easy transport, was located nearly halfway between the two cities. A track that connected a local freight dock ran along the River Dijle bypass at the inner city's ring road, where the rails passed a former Belgian army barracks, named Dossin Barracks (Caserne Dossin) after Lieutenant-General Émile Dossin de Saint-Georges.[8] In the First World War, the division led by General Emile Dossin had put up a brave defense near the River Yser, including at a place named St.-Georges. In recognition, the general received the title Baron de Saint-Georges. At his death in 1936, the old barracks at Mechelen was renamed in his honour. The Germans found this location with minor adaptions required ideal for a transit camp in their Endlösung programme.

Operation

The three-storey block that completely surrounded a large square yard was fitted with barbed wire. The camp staff was mostly German but was assisted by Belgian collaborationists from the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen ("General SS Flanders").[5][9] It was officially under the command of Philipp Schmitt, commandant of the prison camp at Breendonk. The acting commandant at Mechelen was SS officer Rudolph Steckmann.

The first group of people arrived in the camp from Antwerp on 27 July 1942. Between August and December 1942, two transports, each with about 1,000 Jews, left the camp every week for Auschwitz concentration camp. Between the 4 August 1942 and 31 July 1944, a total of 28 trains left Mechelen for Poland, carrying 24,916 Jews and 351 Roma;[1] most of them went to Auschwitz. This figure represented more than half of the Belgian Jews murdered during the Holocaust. In line with the Nazi racial policy that much later became named the Porajmos (or Samudaripen), 351 Belgian Roma were sent to Auschwitz in early 1944.

Conditions at the Mechelen camp were especially brutal. Many Roma were locked in basement rooms for weeks or months at a time without food or sanitary facilities. The Roma had an especially low survival rate.

| Transports | Date | Men | Boys | Women | Girls | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport 1 | 4 August 1942 | 544 | 28 | 403 | 23 | 998 |

| Transport 2 | 11 August 1942 | 459 | 25 | 489 | 26 | 999 |

| Transport 3 | 15 June 1942 | 380 | 48 | 522 | 50 | 1000 |

| Transport 4 | 18 August 1942 | 339 | 133 | 415 | 112 | 999 |

| Transport 5 | 25 August 1942 | 397 | 88 | 429 | 81 | 995 |

| Transport 6 | 29 August 1942 | 355 | 60 | 531 | 54 | 1000 |

| Transport 7 | 1 September 1942 | 282 | 163 | 401 | 154 | 1000 |

| Transport 8 | 10 September 1942 | 388 | 111 | 403 | 98 | 1000 |

| Transport 9 | 12 September 1942 | 408 | 91 | 401 | 100 | 1000 |

| Transport 10 | 15 September 1942 | 405 | 132 | 414 | 97 | 1048 |

| Transport 11 | 26 September 1942 | 562 | 231 | 713 | 236 | 1742 |

| Transport 12 | 10 October 1942 | 310 | 135 | 423 | 131 | 999 |

| Transport 13 | 10 October 1942 | 228 | 89 | 259 | 99 | 675 |

| Transport 14 | 24 October 1942 | 324 | 112 | 438 | 121 | 995 |

| Transport 15 | 24 October 1942 | 314 | 30 | 93 | 39 | 476 |

| Transport 16 | 31 October 1942 | 686 | 16 | 94 | 27 | 823 |

| Transport 17 | 31 October 1942 | 629 | 45 | 169 | 32 | 875 |

| Transport 18 | 15 January 1943 | 353 | 105 | 424 | 65 | 947 |

| Transport 19 | 15 January 1943 | 239 | 51 | 270 | 52 | 612 |

| Transport 20 | 19 April 1943 | 463 | 115 | 699 | 127 | 1404 |

| Transport 21 | 31 July 1943 | 672 | 103 | 707 | 71 | 1553 |

| Transport 22a | 20 September 1943 | 291 | 39 | 265 | 36 | 631 |

| Transport 22b | 20 September 1943 | 305 | 74 | 351 | 64 | 794 |

| Transport 23 | 15 January 1944 | 307 | 33 | 293 | 22 | 655 |

| Transport Z[Note 2] | 15 January 1944 | 85 | 91 | 101 | 74 | 351 |

| transport 24 | 4 April 1944 | 303 | 29 | 275 | 18 | 625 |

| transport 25 | 19 May 1944 | 237 | 20 | 230 | 21 | 508 |

| transport 26 | 31 July 1944 | 280 | 15 | 251 | 17 | 563 |

| Total | August 1942 – July 1944 | 10,545 | 2,212 | 10,463 | 2,047 | 25,267 |

Confrontation

Some people succeeded in escaping the transports, especially from the 16th and 17th transport which consisted of men returned from forced labor on the Atlantic Wall to Belgium. Most of these men jumped between Mechelen and the German border. Many were caught and were soon put on subsequent transports but a total of about 500 Jewish prisoners did manage to escape from all the 28 transports. On April 19, 1943 three resistance fighters, acting on their own initiative, stopped the 20th transport near the train station of Boortmeerbeek, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south-east of Mechelen. From this action 17 prisoners managed to flee. More Jews escaped by their own deeds, a total of 231 Jews fled although 90 were eventually recaptured and 26 were shot by guards escorting the train.[10]

The last transport left on 31 July 1944 but Allied forces could not stop it before its destination was reached. When the Allies approached Mechelen by 3 September 1944, the Germans fled the Dossin camp, leaving the 527 remaining prisoners behind.[5] Some remaining prisoners escaped that night and the others were freed on the 4th, though soon replaced with suspected collaborators. The lists of deportees were left at Hasselt during the German retreat and were later discovered intact.

Memorial and Museum

From 1948 until it was abandoned in 1975, Dossin Barracks was again used by the Belgian Army. Apart from a wing renovated in the 1980s for social housing, the barracks became the site of the Jewish Museum of Deportation and Resistance by 1996. In 2001, the Flemish Government decided to expand the institution by a new complex opposite the old barracks; the latter closed in July 2011, to become a memorial monument.[11] The Kazerne Dossin – Memorial, Museum and Documentation Centre on Holocaust and Human Rights reopened its doors on 26 November 2012.[12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresia of Austria, last of the House of Habsburg, ordered the building of the so-called Hof van Habsburg for an infantry regiment in 1756. Later it became a Belgian Army barracks.

- ↑ Z stands for Zigeuner, Roma in German

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Schram 2006, De raciale deportatie van België naar Auschwitz vanuit Mechelen

- ↑ "Kazerne Dossin – History – Dossin barracks: 1942–44". Cicb.be. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ↑ Mikhman, Gutman & Bender 2005, pp. xxx

- ↑ Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. "The Fate of the Jews – Across Europe Murder of the Jews of Western Europe". Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Schram 2008, Instigators and Perpetrators

- ↑ Schram 2006, De tewerkstelling van degenen die aan de onmiddellijke uitroeiing ontsnappen

- 1 2 "Kazerne Dossin – History – The Transports". Cicb.be. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ↑ "Dossinkazerne (voormalige) (ID: 3617)". De Inventaris van het Bouwkundig Erfgoed. Vlaams Instituut voor het Onroerend Erfgoed (VIOE). Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Mikhman 1998, p. 212

- ↑ Steinberg 1979, pp. 53–56

- ↑ "Kazerne Dossin (main page of August 2011)" (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "Kazerne Dossin: History". Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- Bibliography

- Mikhman, Dan (1998). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-965-308-068-3.

- Mikhman, Dan; Gutman, Israel; Bender, Sara (2005). The encyclopedia of the Righteous among the Nations: rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. Belgium. Yad Vashem.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1999). "Malines, antichambre de la mort". Un pays occupé et ses juifs Belgique entre France et Pays-Bas (in French). Gerpinnes: Quorum. ISBN 978-2-87399-014-5. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Schram, Laurence (2006). "De cijfers van de deportatie uit Mechelen naar Auschwitz. Perspectieven en denkpistes". De Belgische tentoonstelling in Auschwitz. Het boek – L'exposition belge à Auschwitz. Le Livre (in Dutch). Het Joods Museum voor Deportatie en Verzet. ISBN 978-90-76109-03-9. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Schram, Laurence (21 February 2008). "The Transit Camp for Jews in Mechelen: The Antechamber of Death". Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. ISSN 1961-9898. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1979). Extermination, sauvetage et résistance des juifs de Belgique (in French). Brussels: Comité d'hommage des Juifs de Belgique à leurs héros et sauveurs.

- Steinberg, Maxime; Ward, Adriaens; Schram, Laurence; Ramet, Patricia; Hautermann, Eric; Marquenie, Ilse (2009). Mecheln-Auschwitz, 1942–1944 – The destruction of the Jews and Gypsies from Belgium. Vol. I-IV. Brussels: VUBPress. ISBN 978-90-5487-537-6.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1981). Dossier Brussel-Auschwitz, De SS-politie en de uitroeiing van de Joden, gevolg door gerechtelijke documenten van de rechtzaak Ehlers, Canaris en Asche bij het Assisenhof te Kiel, 1980 (in Dutch). Brussel: Steuncomité bij de burgerlijke partij proces tegen SS-Officieren Ehlers, Asche, Canris voor wegvoering der joden van België.

- Steinberg, Maxime; Schram, Laurence (2008). Transport XX : Malines-Auschwitz (in French). Brussels: Éditions du Musée juif de la déportation et de la Resistance. ISBN 978-90-5487-477-5.

- Steinberg, Maxime (2004). La persécution des Juifs en Belgique (1940–1945) (in French). Bruxelles: Complexe. ISBN 978-2-8048-0026-0. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Van Doorslaer, Rudi (2007). La Belgique docile : les autorités belges et la persécution des Juifs en Belgique (in French). Brussels: Luc Pire. ISBN 978-2-87415-848-3.

- Baes, Ruben. "‘La Belgique docile’. Les autorités belges et la persécution des Juifs" [The obedient Belgium – The Belgian authorities and the persecution of the Jews]. Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War And Contemporary Society (CEGES-SOMA). Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- The Kazerne Dossin – Memorial, Museum and Documentation Centre on Holocaust and Human Rights web site. (Accessed 31 July 2011)

- This article incorporates text from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and has been released under the GFDL: Mechelen. Holocaust Encyclopedia. (Accessed 31 July 2011).

External links

- "Transport XX Dossin – Boortmeerbeek – Auschwitz 19 – 04 – 1943". Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Laub, Michel (2 March 2011). "Le projet Kazerne Dossin" (in French). Centre Communautaire Laïc Juif. Retrieved 3 August 2011.