Dorothy Du Boisson

|

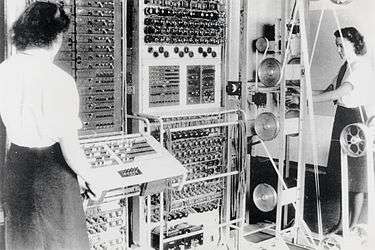

A Colossus Mark 2 computer being operated by Dorothy Du Boisson (left) and Elsie Booker. |

Dorothy Du Boisson, MBE (26 November 1919 – 1 February 2013) was a codebreaker stationed at Bletchley Park during World War II.

Bletchley Park

Du Boisson joined the Women's Royal Naval Service (known as WRNS) in 1943 and was stationed at the Newmanry in Bletchley Park. Along with other WRNS, she operated codebreaking machines, including the Colossus computer. She was set to work on the first Newmanry Tunny and then on Heath Robinson, before eventually move to Colossus. She was one of four operators who was working with Tunny. To work efficiently, she had to learn how to operate Heath Robinson as well. After Colossus appeared, she operated it under the direction of cryptographer.[1]

When more WRNS were posted to the Newmanry, Du Boisson came off the machines and went into the Ops Rooms as a registrar[1]. She was responsible for logging the tapes in and out and distributing them to the machines. Since there had only two people working in Ops room, Du Boisson had tremendous amount of work to do to record the date and the identity of each tape used on Colossus and Tunny. She knew exactly where each tape was and the machine time spent on it. Moreover, she was responsible for unwinding tapes into buckets and joining them into a loop. This was an essential step for operating Colossus and Heath Robinson since the tape might not stand up to the speed of the machine. After many experiments, Du Boisson found a unique way to realize it by using a special glue, a warm clamp, and French chalk. After the European war was over, Colossi were smashed into fragments on the orders of Churchill.[2]

After the war ended, Du Boisson worked as a typist in the Air Ministry.[2]

The working details

To perform the data analyze well, “Du Boisson and other operators in Wrens need to get the data first from a partially electronic machine named Heath Robinson. If it could perform its analysis successfully, the resulting data would be run through the Tunny machine.” [3]

Tensed working schedule

Most of workers aged between 20 and 22, and were put under training sessions in order to get more familiar with the machines, how they operates, what do they do and the maintenance procedures. However, the working shifts could last for long times, up to 70 hours per week.[3] The main reason was that many machines kept running all the time and, since there were few people that actually knew how to operate them, it was necessary to work with three eight-hour shifts every day for weeks. Moreover, due to this stressful working load, many errors in the operations started to appear. Due to limitations in the machines, when a mistake was found, in many cases it was necessary to redo the work all over again.

Harsh living and working conditions

Workers had to perform series of strict jobs within tight schedule. Due to restrictions about outside policies, workers had to spend most the time locked in rooms without proper ventilation and luminosity. Moreover, many employees even lived there, usually in attics, that were not actually prepared: “The attic was cold and very damp”, we had to “put newspapers in the bed to keep warm”. The poor conditions of the buildings and the machinery with lots of electrical cables also were not a good combination, since it was common to have fires. Also, the food condition was not good and the water that was provided had several cases of contamination. “We suffered from exhaust and malnutrition”.[2]

Was unaware of the real purpose of their job

Another particular detail about the job done in Bletchley Park was that employees didn’t know exactly what they were doing and how their work was going to be used. They simply just followed orders given by their superiors and were prohibited to make any question or give any comment about it.

Was unaware of the success of their job

As other members of Wrens, Du Boisson knew little of Bletchley’s successes on the codebreaking. They get some information about what they had been doing once a month. They were also responsible for collecting information for the war. “Every German officer had a card and each time his name appeared in the message, all the details were noted.” Once, we were told, a senior German officer has sent a coded message asking for the luggage of his mistress to be forwarded. Our people were delighted to read it, since his regiment had not been heard of for several months.[2]

The contribution to the D-day and the WW2

The engineer who designed and constructed the prototype Colossus, Thomas Flowers said that “Bletchley Park changed the course of history and the praise that the cryptanalysts have received is well merited, but nothing has ever been said about the many people who worked like slaves for over a year to create Colossus and get it into service by D-day.” Indeed, without the hard working of Du Boisson and other Wren girls, Colossus won’t be able to function well. The fact the first fully satisfactory Colossus was put into service before the D-day was no coincidence. They worked flat out for four months and met the deadline. Is the decoding Bletchley Park did ensure that German couldn’t get the time of American troop’s landing. Eisenhower said, without the information Bletchley had applied, the war would have gone on for at least two years longer than it did.[2]

References

- ↑ Copeland, B. Jack (2010). Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199578141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Du Boisson, Dorothy. "Interview clip". Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 Hicks, Marie (2017). Programmed Inequality, How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03554-5.