Dnieper Hydroelectric Station

| Dnieper Hydroelectric Station | |

|---|---|

|

The dam as seen from Khortytsia Island. | |

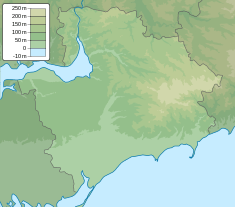

Location of the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station in Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine | |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Location | Zaporizhia |

| Coordinates | 47°52′09″N 35°05′13″E / 47.86917°N 35.08694°ECoordinates: 47°52′09″N 35°05′13″E / 47.86917°N 35.08694°E |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1927 |

| Opening date | October 1932 |

| Owner(s) | Energy Company of Ukraine |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Dnieper River |

| Height | 61 m (200 ft) |

| Length | 800 m (2,600 ft) |

| Reservoir | |

| Active capacity | 33.3 km3 (27,000,000 acre·ft) |

| Power station | |

| Operator(s) | Ukrhydroenergo |

| Installed capacity | 1,569 MW |

The Dnieper Hydroelectric Station (Ukrainian: ДніпроГЕС - DniproHES, Russian: ДнепроГЭС - DneproGES, also known as Dneprostroi Dam) is the largest hydroelectric power station on the Dnieper River, placed in Zaporizhia, Ukraine.

Early plans

In the lower reaches of the Dnieper River there was an almost 100 kilometres (62 mi) long stretch that was filled with rapids. Now this is the distance between the modern cities Dnipro and Zaporizhia. In the 19th century engineers worked on the projects to make the river navigable. The projects for the flooding of the rapids were proposed by N. Lelyavsky in 1893, V. Timonov(RU) in 1894, S. Maximov and Genrikh Graftio in 1905, A. Rundo and D. Yuskevich in 1910, I. Rozov and L. Yurgevich in 1912, Mohylko.[1][2] While the main objective of these projects was to improve navigation, hydropower generation appeared concurrently, in terms of "utilization of the freely flowing water".[3] G. Graftio's(RU) project of 1905 included three dams with a small area of flooding.

GOELRO plan and construction, 1921–1941

Lenin's slogan "Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country" became a motto for Soviet industrialization. On February 7, 1920, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets announced the formation of a State Electrification Commission (GOELRO) under the chairmanship of the Bolshevik electrical engineer, Gleb Krzhizhanovskii. The task of the commission was to devise a general plan for electrifying the country via the construction of a network of regional power stations. Ten months later, GOELRO presented its plan, a document of more than 500 pages, to the Eighth Congress of Soviets in Moscow.

The Dneprostroi Dam was built on deserted land in the countryside to stimulate Soviet industrialization. There was established a special company called Dniprobud or Dneprostroi (hence the dam's alternative name) that later built other dams on the Dnieper and exists to this day. The design for the dam that was accepted dates back to the USSR GOELRO electrification plan which was adopted in early 1920s. The station was designed by a group of engineers headed by Prof. Ivan Alexandrov, a chief expert of GOELRO, who later became a head of the RSFSR State Planning Commission. The station was planned to provide electricity for several aluminium production plants and a high quality steel production plant that were also to be constructed in the area.[4]

The DniproHES project used the experience gained from the construction of the Sir Adam Beck Hydroelectric Power Stations Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, Hydroelectric Island Maligne, La Gabelle Generating Station on the St. Maurice river.[5]

September 17, 1932, for "the outstanding work in the construction of DniproHES" the Soviet government awarded six American engineers (including Hugh Cooper, G. Thompson, the engineer of General Electric), the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.

Soviet Industrialization was accompanied by a wide propaganda effort. Leon Trotsky, by then out of power, campaigned for the idea within the ruling Politburo in early 1926. In a speech to the Komsomol youth movement, he said:[6]

- In the south the Dnieper runs its course through the wealthiest industrial lands; and it is wasting the prodigious weight of its pressure, playing over age-old rapids and waiting until we harness its stream, curb it with dams, and compel it to give lights to cities, to drive factories, and to enrich ploughland. We shall compel it!

The dam and its buildings were designed by the constructivist architects Viktor Vesnin and Nikolai Kolli. Construction began in 1927, and the plant started to produce electricity in October 1932.[4] Generating about 560 MW, the station became the largest Soviet power plant at the time and one of the largest in the world.[4] American specialists under the direction of Colonel Hugh Cooper took part in the construction. The first five giant power generators were manufactured by General Electric. During the second 5-year plan four more generators of similar power produced by Elektrosila in Leningrad were installed.[4] The Dneprostroi Dam was the largest in Europe at the time of its construction.

The industrial centres of Zaporizhia, Kryvy Rih and Dnipro grew from the power provided by the station, including such electricity-consuming industries as aluminium production, which was vitally important for Soviet aviation.

World War II and post-war reconstruction

During World War II, the strategically important dam and plant was dynamited by retreating Red Army troops in 1941 after Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union. American journalist H. R. Knickerbocker wrote that year:[7]

The Russians have proved now by their destruction of the great dam at Dniepropetrovsk that they mean truly to scorch the earth before Hitler even if it means the destruction of their most precious possessions ... Dnieprostroy was an object almost of worship to the Soviet people. Its destruction demonstrates a will to resist which surpasses anything we had imagined. I know what that dam meant to the Bolsheviks ... It was the largest, most spectacular, and most popular of all the immense projects of the First Five-Year Plan ... The Dnieper dam when it was built was the biggest on earth and so it occupied a place in the imagination and affection of the Soviet people difficult for us to realize ... Stalin's order to destroy it meant more to the Russians emotionally than it would mean to us for Roosevelt to order the destruction of the Panama Canal.

The tidal surge killed thousands of unsuspecting civilians, as well as Red Army officers who were crossing over the river.[8] It was partially dynamited again by retreating German troops in 1943. In the end the dam suffered extensive damage, and the powerhouse hall was nearly destroyed. Both were rebuilt between 1944 and 1949.

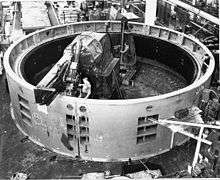

General Electric built the new generators for the Dam. Their weight was more than 2,250,000 pounds. The generators replaced those destroyed during World War II. Each of the new units is rated 90 MW, as compared to the 77.5 MW of the old generators, built in 1931. With a frame diameter of 42 feet 5 inches, units were shipped in 1946.[9]

Power generation was restarted in 1950. In 1969–80, the second powerhouse was built with a production capacity of 828 MW.

Currently, the dam is over 800 meters long and 61 metres high. The dam elevates the river water up to 37 m, which floods the rapids above and makes the entire Dnieper navigable. Over its long history, the dam was hailed as one of the greatest achievements of Soviet industrialization programs.

Post-Soviet time

Today the dam has been privatized and continues to power the adjacent industrial complexes. The pressure of the water leaving the dam is at 38.7 metres and the reservoir that is behind it is 33.3 cubic kilometres. The dam is also used by traffic.

In the spring of 2016 all communist symbols (including the sign that stated that the dam was named after Vladimir Lenin) were removed from the dam in order to comply with decommunization laws.[10]

References

- ↑ (in Russian) Непорожний П. С. Гидроэнергетика и комплексное использование водных ресурсов СССР. — Энергоиздат, 1982. — С. 17. — 559 с.

- ↑ Dnieper Hydroelectric Station // Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ (in Russian) Нестерук Ф. Я. Развитие гидроэнергетики СССР. — Изд-во Академии наук СССР, 1963. — С. 34. — 382 с.

- 1 2 3 4 С. Кульчицький (2004). Україна в системі загальносоюзного народногосподарського комплексу (PDF). Проблеми Історії України: факти, судження, пошуки (in Ukrainian). 11: 30–31.

- ↑ Новицкий В. (2002). Днепрогэс — символ советско-американской дружбы (PDF). 2000 (in Russian) (393): A7.

- ↑ Quoted in Isaac Deutscher. The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky: 1921-1929, Oxford University Press, 1959, reprinted by Verso, 2003, ISBN 1-85984-446-4, p. 178.

- ↑ Knickerbocker, H. R. (1941). Is Tomorrow Hitler's? 200 Questions On the Battle of Mankind. Reynal & Hitchcock. pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Ukrainian Activists Draw Attention To Little-Known WWII Tragedy.

- ↑ Hydro-electric Generator for Russia's Dnieprostroi Dam, 1945. Image #21.009. Science Service Historical Image Collection. National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) In Zaporizhia began to "dekomunizuvaty" DniproGES, Radio Free Europe (4 April 2016)

Further reading

- "Комсомольская правда" об угрозах плотины Киевской ГЭС и водохранилища

- "Аргументы и факты" о реальных угрозах дамбы Киевского водохранилища и ГЭС

- "Известия" о проблематике плотины Киевского водохранилища и ГЭС

- Эксперт УНИАН об угрозах дамбы Киевского водохранилища

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydroelectric power plants in Ukraine. |

- Dnieper Hydroelectric Station // Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Hydroelectric power stations in Ukraine

- (in Russian) Information from site dedicated to 85th anniversary of GOERLO

- Official website of Ukrhydroenergy

- List of power stations in Ukraine

- Zaporizhzhia Pylon Triple