Alanine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Alanine | |

| Other names

2-Aminopropanoic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.249 |

| EC Number | 206-126-4 |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C3H7NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 89.09 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 1.424 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 258 °C (496 °F; 531 K) (sublimes) |

| 167.2 g/L (25 °C) | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.35 (carboxyl), 9.69 (amino)[1] |

| -50.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Alanine (abbreviated as Ala or A; encoded by the codons GCU, GCC, GCA, and GCG) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain methyl group, classifying it as a nonpolar (at physiological pH), aliphatic amino acid. It is non-essential in humans, meaning the body can synthesize it.

The L-isomer (left-handed) of alanine is one of the 20 amino acids encoded by the human genetic code. L-Alanine is second only to leucine in rate of occurrence, accounting for 7.8% of the primary structure in a sample of 1,150 proteins.[2] The right-handed form, D-Alanine occurs in bacterial cell walls and in some peptide antibiotics.

History and etymology

Alanine was first synthesized in 1850 by Adolph Strecker.[3][4][5] The amino acid was named Alanin in German, in reference to aldehyde, with the infix -an- for ease of pronunciation,[6] the German ending -in used in chemical compounds being analogous to English -ine.

Structure

The α-carbon atom of alanine is bound to a methyl group (-CH3), making it one of the simplest α-amino acids and also results in alanine's classification as an aliphatic amino acid. The methyl group of alanine is non-reactive and is thus almost never directly involved in protein function.

Alanine is an amino acid that cannot be phosphorylated, making it quite useful in a loss of function experiment with respect to phosphorylation.

Sources

Dietary sources

Alanine is a nonessential amino acid, meaning it can be manufactured by the human body, hence need not be obtained directly through diet. Alanine is found in a wide variety of foods, but is particularly concentrated in meats.

Good sources of alanine include

- Animal sources: meat, seafood, caseinate, dairy products, eggs, fish, gelatin, lactalbumin

- Vegetarian sources: beans, nuts, seeds, soy, whey, brewer's yeast, brown rice, bran, corn, legumes, whole grains.

Biosynthesis

Alanine can be manufactured in the body from pyruvate and branched chain amino acids such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine.

Alanine is most commonly produced by reductive amination of pyruvate. Because transamination reactions are readily reversible and pyruvate pervasive, alanine can be easily formed and thus has close links to metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the citric acid cycle. It also arises together with lactate and generates glucose from protein via the alanine cycle.

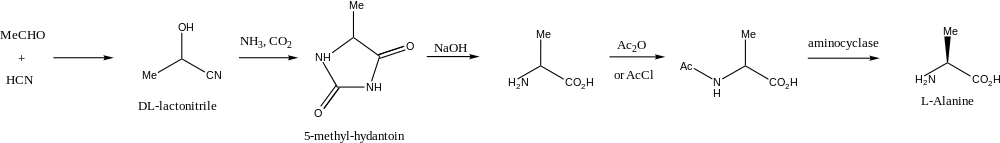

Chemical synthesis

Racemic alanine can be prepared by the condensation of acetaldehyde with ammonium chloride in the presence of sodium cyanide by the Strecker reaction, or by the ammonolysis of 2-bromopropanoic acid:[7]

Physiological function

Glucose–alanine cycle

Alanine plays a key role in glucose–alanine cycle between tissues and liver. In muscle and other tissues that degrade amino acids for fuel, amino groups are collected in the form of glutamate by transamination. Glutamate can then transfer its amino group through the action of alanine aminotransferase to pyruvate, a product of muscle glycolysis, forming alanine and α-ketoglutarate. The alanine formed is passed into the blood and transported to the liver. A reverse of the alanine aminotransferase reaction takes place in liver. Pyruvate regenerated forms glucose through gluconeogenesis, which returns to muscle through the circulation system. Glutamate in the liver enters mitochondria and degrades into ammonium ion through the action of glutamate dehydrogenase, which in turn participate in the urea cycle to form urea.[9]

The glucose–alanine cycle enables pyruvate and glutamate to be removed from the muscle and find their way to the liver. Glucose is regenerated from pyruvate and then returned to muscle: the energetic burden of gluconeogenesis is thus imposed on the liver instead of the muscle. All available ATP in muscle is devoted to muscle contraction.[9]

Link to hypertension

One study reported a correlation between high levels of urinary alanine excretion and higher blood pressure, energy intake, cholesterol levels, and body mass index. The study did not measure dietary alanine or plasma alanine.[10]

Link to diabetes

Alterations in the alanine cycle that increase the levels of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is linked to the development of type II diabetes. With an elevated level of ALT the risk of developing type II diabetes increases.[11]

Chemical properties

Free radical stability

The deamination of an alanine molecule produces a stable alkyl free radical, CH3C•HCOO−. Deamination can be induced in solid or aqueous alanine by radiation.[12]

This property of alanine is used in dosimetric measurements in radiotherapy. When normal alanine is irradiated, the radiation causes certain alanine molecules to become free radicals, and, as these radicals are stable, the free radical content can later be measured by electron paramagnetic resonance in order to find out how much radiation the alanine was exposed to. Radiotherapy treatment plans can be delivered in test mode to alanine pellets, which can then be measured to check that the intended pattern of radiation dose is correctly delivered by the treatment system.

See also

References

- ↑ Dawson, R.M.C., et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ Doolittle, R. F. (1989), "Redundancies in protein sequences", in Fasman, G. D., Prediction of Protein Structures and the Principles of Protein Conformation, New York: Plenum, pp. 599–623, ISBN 0-306-43131-9.

- ↑ Strecker, A. (1850). "Ueber die künstliche Bildung der Milchsäure und einen neuen, dem Glycocoll homologen". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 75 (1): 27–45. doi:10.1002/jlac.18500750103.

- ↑ Strecker, A. (1854). "Ueber einen neuen aus Aldehyd – Ammoniak und Blausäure entstehenden Körper (p )". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 91 (3): 349–351. doi:10.1002/jlac.18540910309.

- ↑ "Alanine".

- ↑ "alanine". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ↑ Kendall, E. C.; McKenzie, B. F. (1929). "dl-Alanine". Org. Synth. 9: 4.; Coll. Vol., 1, p. 21.

- ↑ http://drugsynthesis.blogspot.co.uk/2011/11/laboratory-synthesis-of-l-alanine.html

- 1 2 Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005), Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.), New York: W. H. Freeman, pp. 684–85, ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ↑ Holmes E, Loo RL, Stamler J, Bictash M, Yap IK, Chan Q, Ebbels T, De Iorio M, Brown IJ, Veselkov KA, Daviglus ML, Kesteloot H, Ueshima H, Zhao L, Nicholson JK, Elliott P (2008). "Human metabolic phenotype diversity and its association with diet and blood pressure". Nature. 453 (7193): 396–400. PMID 18425110. doi:10.1038/nature06882.

- ↑ "Elevated Alanine Aminotransferase Predicts New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Independently of Classical Risk Factors, Metabolic Syndrome, and C-Reactive Protein in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study".

- ↑ Zagórski, Z. P.; Sehested, K. (1998), "Transients and stable radical from the deamination of α-alanine", J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem., 232 (1–2): 139–41, doi:10.1007/BF02383729.