Jerash

Coordinates: 32°16′20.21″N 35°53′29.03″E / 32.2722806°N 35.8913972°E

| Jerash جرش Gerasa (Ancient Greek) | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

The Roman city of Gerasa and the modern Jerash (in the background). | |

| Nickname(s): Pompeii of the East, The city of 1000 columns | |

Jerash | |

| Coordinates: 32°16′20.21″N 35°53′29.03″E / 32.2722806°N 35.8913972°E | |

| Country | Jordan |

| Province | Jerash Governorate |

| Founded | 2000 BC. |

| Municipality established | 1910 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| Elevation | 600 m (1,968 ft) |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

| • Total | city (50,745), Municipality (237.000 est) |

| Time zone | GMT +2 |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 (UTC) |

| Area code(s) | +(962)2 |

| Website | http://www.jerash.gov.jo |

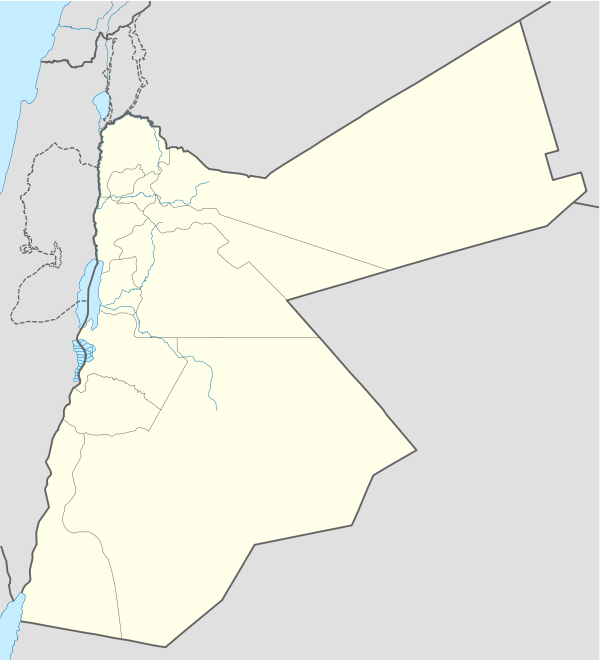

Jerash, the Gerasa of Antiquity (Arabic: جرش, Ancient Greek: Γέρασα), is the capital and the largest city of Jerash Governorate (محافظة جرش), which is situated in the north of Jordan, 48 kilometres (30 mi) north of the capital Amman towards Syria. Jerash Governorate's geographical features vary from cold mountains to fertile valleys from 250 to 300 metres (820 to 980 ft) above sea level, suitable for growing a wide variety of crops.

The history of the city is a blend of the Greco-Roman world of the Mediterranean basin and the ancient traditions of the Arab Orient.[2] The name of the city reflects this interaction. The earliest Arab/Semitic inhabitants, who lived in the area during the pre-classical period of the 1st millennium BCE, named their village Garshu. The Romans later Hellenized the former Arabic name of Garshu into Gerasa. Later, the name transformed into the Arabic Jerash.[3][2]

The city flourished into the mid-eighth century CE, when the 749 Galilee earthquake destroyed large parts of Jerash, while subsequent earthquakes (847 Damascus earthquake) along with wars and turmoil contributed to additional destruction. However, In the early 12th century, by the year 1120, Zahir ad-Din Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus ordered a garrison of forty men stationed in Jerash to convert the Temple of Artemis into a fortress. It was captured in 1121 by Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, and utterly destroyed.[4][5] Then, the Crusaders immediately abandoned Jerash and withdrew to Sakib (Seecip); the eastern border of the settlement.[6][7] Jerash was then deserted until it reappeared in the Ottoman tax registers in the Sixteenth Century[6] (1538, 1548, 1596); it had -for example- a population of 12 households in 1596.[8] However, the archaeologists have found a small Mamluk hamlet in the Northwest Quarter[9] which indicates that Jerash was resettled before the Ottoman era. The excavations conducted since 2011 have shed light on the Middle Islamic period as recent discoveries have uncovered a large concentration of Middle Islamic/Mamluk structures and pottery.[10]

In 1806, the German traveler, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, came across and wrote about the ruins he recognized.[11]

In 1885, the Ottoman authorities directed the Circassian immigrants to settle in Jerash.[12]

The ancient city has been gradually revealed through a series of excavations which commenced in 1925, and continue to this day.[13]

History

Bronze Age

Evidence of settlements dating to the Bronze Age (3200 BC – 1200 BC) have been found in the region.[14][15][16]

Hellenistic period

Jerash is the site of the ruins of the Greco-Roman city of Gerasa, also referred to as Antioch on the Golden River. Ancient Greek inscriptions from the city as well as literary sources from both Iamblichus and the Etymologicum Magnum support that the city was founded by Alexander the Great or his general Perdiccas, who settled aged Macedonian soldiers there. This took place during the spring of 331 BC, when Alexander left Egypt, crossed Syria and then went to Mesopotamia.

Roman period

After the Roman conquest in 63 BC, Jerash and the land surrounding it were annexed to the Roman province of Syria, and later joined the Decapolis league of cities. In AD 90, Jerash was absorbed into the Roman province of Arabia, which included the city of Philadelphia (modern day Amman). The Romans ensured security and peace in this area, which enabled its people to devote their efforts and time to economic development and encouraged civic building activity.

Jerash is considered to be one of the most original and best preserved Roman cities in the Near East.[17] and is sometimes misleadingly referred to as the "Pompeii of the Middle East" or of Asia, referring to its size, extent of excavation and level of preservation, since Jerash was never destroyed and buried by a single cataclysmic event, such as a volcanic eruption.

Jerash was the birthplace of the mathematician Nicomachus of Gerasa (Greek: Νικόμαχος) (c. 60 – c. 120 AD).

In the second half of the 1st century AD, the city of Jerash achieved great prosperity. In AD 106, the Emperor Trajan constructed roads throughout the province, and more trade came to Jerash. The Emperor Hadrian visited Jerash in AD 129–130. The triumphal arch (or Arch of Hadrian) was built to celebrate his visit. A remarkable Latin inscription records a religious dedication set up by members of the imperial mounted bodyguard wintering there.

Byzantine period

The city finally reached a size of about 800,000 square meters within its walls. The Persian invasion in AD 614 caused the rapid decline of Jerash. Beneath the foundations of a Byzantine church that was built in Jerash in AD 530 there was discovered a mosaic floor with Hebrew inscription, believed to have once been a synagogue.[18]

Early Muslim period

Despite its decline, the city continued to flourish during the Umayyad period, as shown by recent excavations. In AD 749, a major earthquake destroyed much of Jerash and its surroundings.

Crusader period

During the period of the Crusades, some of the monuments were converted to fortresses, including the Temple of Artemis.

Mid to Late Muslim period

Small settlements continued in Jerash during the Mamluk Sultanate, and Ottoman periods. Patricullary in the Northwest Quarter and around the Temple of Zues, where several Middle Islamic/Mamluk domestic structures have now been excavated.

Climate

| Climate data for Jerash, Jordan (648M) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.2 (63) |

22.2 (72) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.0 (86) |

26.7 (80.1) |

21 (70) |

14.7 (58.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14 (57) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

17.2 (63) |

14 (57) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.72 (53.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92 (3.62) |

91 (3.58) |

66 (2.6) |

19 (0.75) |

5 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (0.28) |

38 (1.5) |

75 (2.95) |

393 (15.47) |

| Source: climate Data [19] | |||||||||||||

Archaeology

Excavation and restoration of Jerash has been almost continuous since the 1920s.

Neolithic age

In August 2015, two human skulls dating back to Neolithic period unearthed in Jerash which forms solid evidence of inhabitance of Jordan in that period especially with the existence of 'Ain Ghazal Neolithic settlement in Amman.

An archaeological excavation team from the University of Jordan has recently unearthed two human skulls that date back to the Neolithic period (7500–5500 BC) at a site in Jerash.

The importance of the discovery lies in the rarity of the skulls, as archaeologists estimate that a maximum of 12 sites across the world contain similar human remains.[20]

Greco-Roman period

Remains in the Greco-Roman Jerash include:

- Numerous Corinthium columns

- Hadrian's Arch

- The circus/hippodrome

- The two large temples (dedicated to Zeus and Artemis)

- The nearly unique oval Forum, which is surrounded by a fine colonnade,

- The long colonnaded street or cardo

- Two theatres (the Large South Theatre and smaller North Theatre)

- Two communal baths, and a scattering of small temples

- A large Nymphaeum fed by an aqueduct

- An almost complete circuit of city walls

- A water powered saw mill for cutting stone

- Two large bridges across the nearby river.

Most of these monuments were built by donations of the city's wealthy citizens. The south theatre has a focus in the centre of the pit in front of the stage, marked by a distinct stone, and from which normal speaking can be heard easily throughout the auditorium. From AD 350, a large Christian community lived in Jerash, and between AD 400–600, more than thirteen churches were built, many with superb mosaic floors. A cathedral was built in the 4th century. An ancient synagogue with detailed mosaics, including the story of Noah, was found beneath a church. The use of water power to saw wood or stone is well known in the Greek and Roman world, the invention in Greece occurring in the 3rd century BC. They converted rotary movement from the mill to linear motion using a crankshaft and good examples are known from Hierapolis and Ephesus to the north. The mill is well described in the visitors centre, and is situated near the Temple of Artemis.

Modern Jerash

Jerash has developed dramatically in the last century with the growing importance of the tourism industry to the city. Jerash is now the second-most popular tourist attraction in Jordan, closely behind the splendid ruins of Petra. On the western side of the city, which contained most of the representative buildings, the ruins have been carefully preserved and spared from encroachment, with the modern city sprawling to the east of the river which once divided ancient Jerash in two.

Territorial expansion

Recently the city of Jerash has expanded to include many of the surrounding areas.

Demographic evolution

Jerash became a destination for many successive waves of foreign migrants. The first wave started during the late 19th century with groups of Circassians, followed during the first half of the 20th century by Syrians (Shwam), all camping near the old ruins. The new immigrants have been welcomed by the local people and settled down in the reemerging city. Later, Jerash also witnessed waves of Palestinian refugees who flowed to the city in 1948 and 1967.

Jerash has an ethnically diverse population, with the majority being Arabs. Circassians and Armenians also live there in a small percentage. The majority of Jerash's population are Muslims. However, the percentage of Christians (Orthodox and Catholics) in Jerash city is slightly higher than some other cities in Jordan.

According to the Jordan national census of 2004, the population of Jerash City was 31,650 and was ranked as the 14th largest municipality in Jordan. The estimated population in 2010 is about 42,000. The National census of 2004 showed that the population of the province of Jerash Governorate was 153,650.[21] 78,440 (51%) of the population was urban and 75,162 was rural. Jordanian citizens made up 87.1% of the population of Jerash Governorate. The male to female ratio was 51.48 to 48.51.[22] Jerash Governorate has the second highest density in Jordan (after Irbid Governorate).

Culture and entertainment

Since 1981, the old city of Jerash has hosted the Jerash Festival of Culture and Arts,[23] a three-week-long summer program of dance, music, and theatrical performances. The festival is frequently attended by members of the royal family of Jordan and is hailed as one of the largest cultural activities in the region.

In addition performances of the Roman Army and Chariot Experience (RACE) were started at the hippodrome in Jerash. The show runs twice daily, at 11am and at 2pm, and at 10am on Fridays, except Tuesdays. It features forty-five legionaries in full armour in a display of Roman army drill and battle tactics, ten gladiators fighting "to the death" and several Roman chariots competing in a classical seven-lap race around the ancient hippodrome.

Economy

Jerash's economy depends largely on the tourists who visit the ancient city. It is also an agricultural city with over 1.25 million olive trees in the Governorate.[24] However, the location of Jerash, being just half an hour ride from two of the largest cities in Jordan, Amman and Irbid, contributed to the slowing down of Jerash's development, as investments tend to go to the larger cities. Jerash has two universities; Jerash Private University and Philadelphia University, and they are located on the highway from Jerash to Amman.[25]

Tourism

The number of tourists who visited the ancient city of Jerash reached 214,000 during 2005. The number of non-Jordanian tourists was 182,000 last year, and the sum of entry charges reached JD900,000.[26] The Jerash Festival of Culture and Arts is an annual celebration of Arabic and international culture during the summer months. Jerash is located 46 km north of the capital city of Amman. The festival site is located within the ancient ruins of Jerash, some of which date to the Roman age (63 BC).[27] Jerash Festival is a festival which features poetry recitals, theatrical performances, concerts and other forms of art.[28] In 2008, authorities launched Jordan Festival, a nationwide theme-oriented event under which Jerash Festival became a component.[29] however the government revived the Jerash Festival as the "substitute proved to be not up to the message intended from the festival."

Gallery

Oval Forum

Oval Forum North Theater

North Theater The cardo maximus

The cardo maximus The hippodrome

The hippodrome.jpg) Enriched mouldings on the Temple of Artemis

Enriched mouldings on the Temple of Artemis Northern Tetrapylon, Jerash

Northern Tetrapylon, Jerash North Tetrapylon, Jerash

North Tetrapylon, Jerash View of Columns at Jerash

View of Columns at Jerash Ornamentation, Jerash

Ornamentation, Jerash Inside Jerash

Inside Jerash Jerash ornamentation

Jerash ornamentation Jerash ornamentation

Jerash ornamentation Inside Jerash

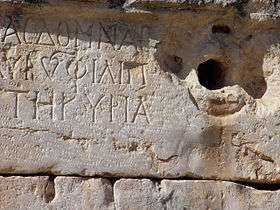

Inside Jerash Inscriptions at Jerash

Inscriptions at Jerash

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.citypopulation.de/Jordan-Cities.html

- 1 2 Bell, Brian (1994). Jordan. APA Publications (HK) Limited. p. 184.

- ↑ McEvedy, Colin (2011). Cities of the Classical World: An Atlas and Gazetteer of 120 Centres of Ancient Civilization. UK: Penguin. ISBN 0141967633.

- ↑ Boulanger, Robert (1965). The Middle East: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran. Paris: Hachette. pp. 541, 542.

- ↑ Heath, Ian (1980). A wargamers' guide to the Crusades. p. 133.

- 1 2 Brooker, Colin H.; Knauf, Ernst Axel (1988). "Review of Crusader Institutions". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-). 104: 187.

- ↑ Schryver, James G (2010). Studies in the archaeology of the medieval Mediterranean. Leiden [Netherlands]; Boston: Brill. pp. 86. ISBN 9789004181755.

- ↑ Hütteroth, Wolf Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the late 16th [sixteenth] century. Fränkische Geographische Ges. p. 164. ISBN 9783920405414.

- ↑ "Archaeologists studying a post-quake gap in Jerash history". Jordan Times. 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- ↑ Peterson, Alex. "Medieval Pottery from Jerash: The Middle Islamic Settlement". Gerasa/Jerash: From the Urban Periphery.

- ↑ Reisen, ed. Kruse, 4 vols, Berlin, 1854

- ↑ "The Circassians in Jordan". 2004-08-20. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- ↑ "Touristic Sites - Jerash". www.kinghussein.gov.jo.

- ↑ McGovern, Patrick E.; Brown, Robin (1986). Late Bronze & Early Iron Ages of Central. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-934718-75-2.

- ↑ Nigro, Lorenzo (2008). An Early Bronze Age Fortified Town in North-Central Jordan. Preliminary Report of the First Season of Excavations (2005). Lorenzo Nigro. p. 52. ISBN 978-88-88438-05-4.

- ↑ Steiner, Margreet L.; Killebrew, Ann E. (2014). "Main Settlements of the North Jordan Uplands". The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000–332 BCE. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-166255-3.

- ↑ Jerusalem Israel, Petra & Sinai EyeWitness Travel 2016 page 214 ISBN 978-1-4654-4131-7

- ↑ Samuel Klein, Sefer ha-Yishuv, vol. 1, Jerusalem 1939, p. 34 and folio "chet" on pp. 40–41

- ↑ "CLIMATE: Jerash". Climate-Data. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ "Two human skulls dating back to Neolithic period unearthed in Jerash". 15 August 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Jordan National Census, Arabic Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jordan Census Data 2004 Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jerash Festival Of Culture & Arts مهرجان جرش للثقافة والفنون

- ↑ "صحيفة الرأي :: الرئيسية". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Jerash Private University". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Jerash tourism figures reviewed. (2006, Jan 05). Info – Prod Research (Middle East). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/457494325

- ↑ Schneider, I., & SoKnmez, S. (1999). Exploring the touristic image of jordan. Tourism Management, 20, 539–542.

- ↑ Jerash festival to be revived. (2011, Mar 07). Jordan Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/855638491

- ↑ Jerash festival, (2011, Jun 19). McClatchy – Tribune Business News. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/872459474

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jerash. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jerash. |

- Brown, J., E. Meyers, R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. "Places: 678158 (Gerasa/Antiochia ad Chrysorhoam)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.