Diverging diamond interchange

A diverging diamond interchange (DDI), also called a double crossover diamond interchange (DCD),[1] is a type of diamond interchange in which the two directions of traffic on the non-freeway road cross to the opposite side on both sides of the bridge at the freeway. It is unusual in that it requires traffic on the freeway overpass (or underpass) to briefly drive on the opposite side of the road from what is customary for the jurisdiction. The diverging diamond interchange was listed by Popular Science magazine as one of the best innovations in 2009 (engineering category) in "Best of What's New 2009".[2]

Like the continuous flow intersection, the diverging diamond interchange allows for two-phase operation at all signalized intersections within the interchange. This is a significant improvement in safety, since no long turns (e.g. left turns where traffic drives on the right side of the road) must clear opposing traffic and all movements are discrete, with most controlled by traffic signals.[3]

Additionally, the design can improve the efficiency of an interchange, as the lost time for various phases in the cycle can be redistributed as green time—there are only two clearance intervals (the time for traffic signals to change from green to yellow to red) instead of the six or more found in other interchange designs.

History

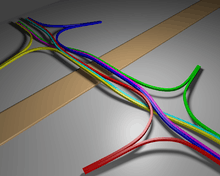

Top left: Traffic enters the interchange along Missouri Route 13

Top right: Traffic crosses over to the left side of the road

Bottom left: Traffic crosses over Interstate 44

Bottom right:Traffic crosses back over to the right side of the road.

Prior to 2009 the only known diverging diamond interchanges were in France in the communities of Versailles, Le Perreux-sur-Marne and Seclin, all built in the 1970s.[4] (The ramps of the first two have been reconfigured to accommodate ramps of other interchanges, but they continue to function as diverging diamond interchanges.)

Despite the fact that such interchanges already existed, the idea for the DDI was "reinvented" around 2000, inspired by the former "synchronized split-phasing" type freeway-to-freeway interchange between Interstate 95 and I-695 north of Baltimore.[5]

In 2005, the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) considered reconfiguring the existing interchange on Interstate 75 at U.S. Route 224 and State Route 15 west of Findlay as a diverging diamond interchange to improve traffic flow. Had it been constructed, it would have been the first DDI in the United States.[6] By 2006, ODOT had reconsidered, instead adding lanes to the existing overpass.[7][8]

The Missouri Department of Transportation was the first US agency to construct one, in Springfield at the junction between I-44 and Missouri Route 13 (at 37°15′01″N 93°18′39″W / 37.2503°N 93.3107°W). Construction began the week of January 12, 2009, and the interchange opened on June 21, 2009.[9][10] This interchange was a conversion of an existing standard diamond interchange, and used the existing bridge.

The interchange in Seclin (at 50°32′41″N 3°3′21″E / 50.54472°N 3.05583°E) between the A1 and Route d'Avelin was somewhat more specialized than in the diagram at right: eastbound traffic on Route d'Avelin intending to enter the A1 northbound must keep left and cross the northernmost bridge before turning left to proceed north onto A1; eastbound traffic continuing east on Route d'Avelin must select a single center lane, merge with A1 traffic that is exiting to proceed east, and cross a center bridge. All westbound traffic that is continuing west or turning south onto A1 uses the southernmost bridge.

Additional research was conducted by a partnership of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and the Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center and published by Ohio Section of the Institute of Transportation Engineers.[11] The Federal Highway Administration released a publication titled "Alternative Intersections/Interchanges: Informational Report (AIIR)" [12] with a chapter dedicated to this design.

Usage

Operational

As of July 2017, 93 DDIs were operational across the world including:

- 3 in France

- 1 in South Africa

- 1 in the United Arab Emirates

- 88 in the United States of America[13]

Proposed

- Denmark - In 2015 plans were made to build Denmark's first DDI (in Danish, a Dynamisk Ruderanlæg) at the junction (exit 52) between E20 (the Funen Motorway; in Danish, Fynske Motorvej) and Secondary Route 168 (Assensvej), in Odense (at 55°21′41″N 10°20′42″E / 55.361287°N 10.344932°E), replacing an existing diamond interchange. Construction of the interchange is scheduled to begin in the summer of 2016 and is expected to be complete by the end of 2017.[14][15]

- Australia - Caloundra Road interchange on the Bruce Highway (Exit 188) in the Sunshine Coast Region of Queensland as part of a wider upgrade. Construction begins May 2017 and expected to be complete late 2020.[16]

- Canada - 162 Avenue interchange on Macleod Trail in Calgary built to enable free-flow traffic on Macleod Trail. Construction begins in fall of 2015 and is anticipated to be completed in fall of 2017.

- Canada - Pilot Butte Access Road Interchange, as part of the Regina Bypass in Saskatchewan, is being constructed over Highway 1 with access to Pilot Butte. Construction began in 2016 and is planned to be complete in the fall of 2018.[17]

Advantages

- Two-phase signals with short cycle lengths, significantly reducing delay.

- Reduced horizontal curvature reduces risk of off-road crashes.

- Increases the capacity of turning movements to and from the ramps.

- Potentially reduces the number of lanes on the crossroad, minimizing space consumption.

- Reduces the number of conflict points, thus theoretically improving safety.

- Increases the capacity of an existing overpass or underpass, by removing the need for turn lanes.

Disadvantages

- Drivers may not be familiar with configuration, particularly with regards to merging maneuvers along the opposite side of the roadway or the crossover flow of traffic.

- Pedestrian (and other sidewalk user) access requires at least four crosswalks (two to cross the two signalized lane crossover intersections, while two more cross the local road at each end of the interchange).[18] This could be mitigated by signalizing all movements, without impacting the two-phase nature of the interchange’s signals.

- Free-flowing traffic in both directions on the non-freeway road is impossible, as the signals cannot be green at both intersections for both directions simultaneously.

- Highway bus stops are appropriately sited outside the interchange.

- Allowing exiting traffic to reenter the through road in the same direction requires leaving the interchange on the local road and turning around, e.g., via a median U-turn crossover. This affects several use cases:

- Drivers who take the wrong exit

- Bypassing a crash at the bridge

- Allowing an oversize load to bypass a low bridge

Further considerations

- No standards currently exist for this design

- The design depends on site-specific conditions.

- Additional signage, lighting, and pavement markings are needed beyond the levels for a standard diamond interchange.

- Local road should be a low speed facility, preferably under 45 mph (72 km/h) posted speed on the crossroad approach. However this may be mitigated by utilizing a higher design speed for the crossing movements.

Double Crossover Merging Interchange

A free-flowing interchange variant, patented in 2015,[19] has received recent attention.[20][21][22] Called the double crossover merging interchange (DCMI), it includes elements from the diverging diamond interchange, the tight diamond interchange, and the stack interchange. It eliminates the disadvantages of weaving and of merging into the outside lane from which the standard DDI variation suffers. As of 2016, no such interchanges have been constructed.

See also

References

- ↑ Hughes, Warren; Jagannathan, Ram (October 2009). "Double Crossover Diamond Interchange". Federal Highway Administration. FHWA-HRT-09-054. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Gallery: Looking Back at the 100 Best Innovations of 2009". Popular Science. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Diverging Diamond Interchange". OHM Advisors.

- ↑ Staff (June 13, 2013). "I-64 Interchange at Route 15, Zion Crossroads". Virginia Department of Transportation. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ Chlewicki, Gilbert (2003). "New Interchange and Intersection Designs: The Synchronized Split-Phasing Intersection and the Diverging Diamond Interchange" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Patch, David (May 2, 2005). "French Connection May Control Traffic Flow". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ Sedensky, Matt (March 30, 2006). "Missouri Drivers May Go to the Left". Star-News. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Wrong Way? Not in Kansas City". Land Line Magazine. March 31, 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ Staff (April 2009). "I-44/Route 13 Interchange Reconstruction: Diverging Diamond Design". Missouri Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- ↑ Springfield District Office (June 19, 2008). "Public Meeting Tuesday, June 24, On I-44/Route 13 Reconstruction To Reduce Congestion, Improve Safety" (Press release). Missouri Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ↑ Edara, Praveen K.; Bared, Joe G. & Jagannathan, Ramanujan. "Diverging Diamond Interchange and Double Crossover Intersection: Vehicle and Pedestrian Performance" (PDF).

- ↑ Hughes, Warren; Jagannathan, Ram; Sengupta, Dibu & Hummer, Joe (April 2010). Alternative Intersections/Interchanges: Informational Report (AIIR) (Report). Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ "Alternative Intersections and Interchanges". Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ↑ "Dynamisk Ruderanlæg - Odense SV" (in Danish). Danish Road Directorate. June 1, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Arkena - Web TV". Dynamisk Ruderanlæg (video) (in Danish). Danish Road Directorate. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Bruce Highway Upgrade – Caloundra Road to Sunshine Motorway". Department of Transport and Main Roads. Queensland Government. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ http://www.reginabypass.ca/project/project-schedule/

- ↑ "The 'Diverging Diamond' Interchange Is an Abomination - Sarah Goodyear". The Atlantic Cities. 2011-09-20. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ "United States Patent 8,950,970: Double Crossover Merging Interchange". United States Patent and Trademark Office. February 10, 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "TRAFFIC ENGINEERING COUNCIL BEST PAPER and BEST PRODUCT AWARD: Past Recipients". Institute of Transportation Engineers. 2016. Archived from the original on October 4, 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Alternative Intersections & Interchanges Symposium" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. July 21, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ Buteliauskas, Stanislovas; Juozapavičius, Aušrius (June 15, 2014). "Interchange of a New Generation Pinavia" (PDF). Military Academy of Lithuania. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Further reading

- Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center. "Drivers' Evaluation of the Diverging Diamond Interchange". Federal Highway Administration. FHWA-HRT-07-048.

- Innovations Library (May 2010). "Missouri's Experience with a Diverging Diamond Interchange: Lessons Learned" (PDF). Missouri Department of Transportation.

- Chlewicki, Gilbert (2003). "New Interchange and Intersection Designs: The Synchronized Split-Phasing Intersection and the Diverging Diamond Interchange" (PDF). Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- Chlewicki, Gilbert (December 4, 2011). "About Chlewicki". The Diverging Diamond Interchange Website. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diverging diamond interchange. |

- DDI Guideline – A UDOT Guide to Diverging Diamond Interchanges, Utah Department of Transportation, June 2014

- Transportation engineers discuss the design of the fifth U.S. DDI in Alcoa, TN

- Video of Paramics Traffic Simualtion software modeling a Double Crossover Diamond Interchange

- Diverging Diamond Interchange Visualization, Instructional video on how to drive in a DDI, NCDOTcommunications, published on 10 March 2011

- Images of Diverging Diamond Interchange in Springfield, Missouri the first in North America.

- Animation of Diverging Diamond Interchange under construction at Elmhurst Road on Interstate 90 near Elk Grove, Illinois, to be completed in 2016

- Animation of Diverging Diamond Interchange at I-590/Winton Road (Rochester, New York)

Examples

- 48°49′56″N 2°09′10″E / 48.832115°N 2.152859°E Map of a diverging diamond interchange in Versailles, France

- 48°49′49.1″N 2°29′35.3″E / 48.830306°N 2.493139°E Map of a diverging diamond interchange in Le Perreux-sur-Marne, France

- 50°32′41.2″N 3°3′20.9″E / 50.544778°N 3.055806°E Map of a diverging diamond interchange in Seclin, France