Diurnality

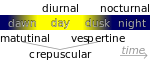

Diurnality is a form of plant or animal behavior characterized by activity during the day, with a period of sleeping, or other inactivity, at night. The common adjective used for daytime activity is "diurnal". The timing of activity by an animal depends on a variety of environmental factors such as the temperature, the ability to gather food by sight, the risk of predation, and the time of year. Diurnality is a cycle of activity within a twenty-four-hour period; cyclic activities called circadian rhythms are endogenous cycles not dependent on external cues or environmental factors. Animals active at dawn or dusk are crepuscular, those active at night are nocturnal, and animals active at sporadic times during both night and day are cathemeral.

Plants that open their flowers during the day are referred to as diurnal, while those that bloom at night are nocturnal. The timing of flower opening is often related to the time at which preferred pollinators are foraging. For example, sunflowers open during the day in order to attract bees; the night-blooming cereus, in contrast, opens at night in order to attract large sphinx moths.

In animals

Many animal species are diurnal, including many mammals, insects, reptiles and birds. In some animals, especially insects, external patterns of the environment control the activity (exogenous rhythms, as opposed to patterns inherent in the habitat).[1] Diurnality is descriptive; it refers to an observed 24-hour pattern, as opposed to ~24-hour circadian rhythms which are self-sustaining within the organism.[2]

In many species, the animal switches from nocturnal to diurnal foraging depending on the environmental temperature. This allows the individual to maximize its feeding efficiency during the warmer summer and lower its risk of predation during the winter.[3] Diurnal insects include some bees, such as Anthidium maculosum. These carder bees are diurnal and active only when the temperatures are above freezing. They are also `most active when there are plenty of resources such as flowers, from which they can extract pollen and nectar.[4]

Some primarily nocturnal or crepuscular animals, like dogs and cats, have been domesticated and have become diurnal to coincide with the cycle of human life. However, these animals may exhibit their species' original behavior when they are born feral. Other animals have been forced from their normal cycle to an alternate one as a means of avoiding predators, such as beavers becoming nocturnal creatures after extended predation by humans.

In plants

Many plants are diurnal or nocturnal, depending on the time period when the most effective pollinators, i.e., insects, visit the plant. Most angiosperm plants are visited by various insects, so the flower adapts its phenology to the most effective pollinators. Thus, the effectiveness of relative diurnal or nocturnal species of insects affects the diurnal or nocturnal nature of the plants they pollinate, causing in some instances an adjustment of the opening and closing cycles of the plants.[5] For example, the baobab is pollinated by fruit bats and starts blooming in late afternoon; the flowers are dead within twenty-four hours.[6]

In technology operations

Services that alternate between high and low utilization in a daily cycle are described as being diurnal. Many web sites have the most users during the day and little utilization at night, or vice versa. Operations planners can use this cycle to plan, for example, maintenance that needs to be done when there are fewer users on the web site.[7]

See also

| Look up diurnal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

- ↑ Gullan, P. J. and P. S. Cranston, 1994. The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. Chapman and Hall London. pg. 115.

- ↑ Klerman, Elizabeth B. (2005). "Clinical Aspects of Human Circadian Rhythms" (PDF). J Biol Rhythms. SagePub. 20 (4): 375–386. doi:10.1177/0748730405278353. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ Fraser, Neil HC, Niel B. Metcalfe, and John E. Thorpe. "Temperature-dependent switch between diurnal and nocturnal foraging in salmon." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 252.1334 (1993): 135-139.

- ↑ Griswold, Terry, Victor H. Gonzalez, and Harold Ikerd. "AnthWest, occurrence records for wool carder bees of the genus Anthidium (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae, Anthidiini) in the Western Hemisphere." ZooKeys 408 (2014): 31.

- ↑ Diurnal and Nocturnal Pollination Article

- ↑ Hankey, Andrew (February 2004). "Adansonia digitata A L.". plantzafrica. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Thomas A. Limoncelli; Strata R. Chalup; Christina J. Hogan (30 March 2014). The Practice of Cloud System Administration: Designing and Operating Large Distributed Systems. Addison Wesley Professional. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-321-94318-7.