Dissent Channel

The Dissent Channel is a messaging framework open to Foreign Service Officers, and other U.S. citizens employed by the United States Department of State and Agency for International Development (USAID),[lower-alpha 1] through which they are invited to express constructive criticism of government policy. The Dissent Channel was established in the 1970s.

Submissions through the Dissent Channel circulate to senior State Department officials; under department regulations, diplomats who submit dissent cables are supposed to be protected from retaliation or reprisal.

History and uses

The Dissent Channel was established in 1971,[2] as a response to concerns that dissenting opinions and constructive criticism were suppressed or ignored during the Vietnam War.[1] Secretary of State William P. Rogers created the system.[3] In February 1971, the right of Foreign Service officers to dissent was explicitly codified in the Foreign Affairs Manual.[4]

The Dissent Channel is reserved for "...consideration of responsible dissenting and alternative views on substantive foreign policy issues that cannot be communicated in a full and timely manner through regular operating channels or procedures."[5] Use of the channel is reserved for dissenting or alternative views on policy concerns; views on "management, administrative, or personnel issues that are not significantly related to matters of substantive foreign policy may not be communicated through the Dissent Channel."[5] Messages sent to the Dissent Channel are distributed to senior members of the State Department's Policy Planning Staff, must be acknowledged within 2 days, and must receive a response within 30–60 days.[5]

Diplomats who write such dissent cables are supposed to be protected from retaliation or reprisal.[2][3] The Foreign Affairs Manual provides that "[f]reedom from reprisal for Dissent Channel users is strictly enforced."[5] Nevertheless, many U.S. diplomats fear to use the channel for fear of retaliation.[6]

From 1971 to 2011, there were 123 dissent cables.[6] The most dissent cables sent in a single year came in 1977, when 28 dissent cables were filed "under the Carter Administration, which everyone agrees created an atmosphere in which use of the channel was encouraged—or at least not stigmatized."[6] After Ronald Reagan became president, the number of dissent cables declined sharply, to 15 in 1981 and just five in 1982. This decline was due to a feeling in "U.S. embassies around the world ... that the Reagan White House and State Department were not receptive to viewpoints that diverged from the ambassadors' assessments," and that dissenting cables was likely to damage a diplomat's career.[7]

Some notable uses of the Dissent Channel include:

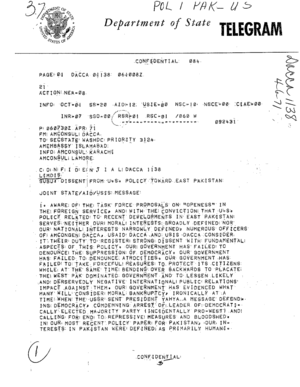

- In March 1971, Archer Blood, the U.S. consul-general in Dhaka, joined by 28 other U.S. diplomats, sent the famous Blood telegram. The cable condemned the U.S. policy of support for Pakistani dictator Yahya Khan, who oversaw a genocide in East Pakistan (later Bangladesh).[6][8]

- In 1992, several Foreign Service officers used the channel to protest U.S. failure to act during the Bosnian genocide.[2][3] The cable is credited with helping lead to the Dayton Accords.[3]

- In 1994, four career diplomats at the U.S. Embassy in Dublin sent a dissent memorandum questioning the decision of U.S. Ambassador Jean Kennedy Smith to grant a U.S. visa to Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams. Two of the four signatories received career-damaging performance appraisals from Smith and were "excluded from Embassy functions relevant to their jobs."[9] This led to a yearlong investigation by the State Department Inspector General's office, which issued a "scathingly critical" report[10] that found "inescapable evidence" that Smith had retailiated against the two diplomats.[9]

- In early 2003, Ann Wright, the chargé d'affaires in Mongolia, used the channel to protest the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq.[2][11] John Brady Kiesling, another U.S. diplomat, also used the dissent cable to express opposition to the war.[12][13] In 2004, diplomat Keith W. Mines, then posted to Budapest, sent a dissent cable arguing that the United Nations should be given charge over the political transition in Iraq.[14]

- In June 2016, 51 Foreign Service officers used the channel to protest the U.S.'s failure to intervene in Syria, a record number at the time.[13][15] The cable—a draft copy of which was obtained by The New York Times—called for limited military strikes against the Assad regime.[15]

- In 2017, about 1,000 Foreign Service officers signed a dissent cable condemning Donald Trump's Executive Order 13769, which imposed a travel and immigration ban on the nationals of seven majority-Muslim countries.[16] This is by far the largest number to ever sign on to a dissent cable.[13][17]

Dissent cables are intended to be internal and not immediately made public, although leaks do occur.[2] Some dissent cables are marked as sensitive but unclassified.[15] Wayne Merry, a former U.S. diplomat who wrote a dissent cable in 1994 while posted to Russia, made a Freedom of Information Act request in 1999 for a copy of his own cable; the State Department denied the request in 2003 on the grounds that (1) "release and public circulation of Dissent Channel messages, even as in your case to the drafter of the message, would inhibit the willingness of Department personnel to avail themselves of the Dissent Channel to express their views freely" and (2) "Dissent Channel messages are deliberative, pre-decisional and constitute intra-agency communications."[18]

Constructive Dissent Award

Foreign service members who make constructive use of the Dissent Channel may be eligible to receive the American Foreign Service Association's Constructive Dissent Awards (although use of the channel is not required to be eligible).[19]

Similar mechanisms

USAID also has a similar channel, the Direct Channel, established in 2011. Unlike the Dissent Channel, this is open to foreign national employees of USAID, and contractors.[20][21]

The Central Intelligence Agency has "red teams" of intelligence officers and analysts "dedicated to arguing against the intelligence community's conventional wisdom and spotting flaws in logic and analysis."[3] Neal Katyal writes that the State Department's Dissent Channel is analogous, and argues that the federal government needs more such intra-agency checks in order to institutionalize the practice of dissent.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Prior to the disestablishment of the U.S. Information Agency and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, employees of those agencies could use the Dissent Channel as well.[1]

References

- 1 2 Christopher, Warren (1995-08-08). "Secretary of State Christopher's Message on the Dissent Channel". US Department of State Archive, Information Released January 20, 2001 through January 20, 2009. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paul D. Wolfowitz, A Diplomat's Proper Channel of Dissent, The New York Times (January 31, 2017).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Neal K. Katyal, Washington Needs More Dissent Channels, The New York Times (July 1, 2016).

- ↑ Jones, David T (2000). "Advise and Dissent: The Diplomat as Protester" (PDF). Foreign Service Journal: 36–40.

- 1 2 3 4 "2 FAM 070 General Administration – Dissent Channel". Foreign Affairs Manual. United States Department of State. 2011-09-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Kishan S. Rana, The Contemporary Embassy: Paths to Diplomatic Excellence (Palgrave Macmillian, 2003), pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Morris Morley & Chris McGillion, Reagan and Pinochet (Cambridge University Press), p. 27 (citing Kai Bird, "Ronald Reagan's Foreign Service," APF Reporter 7, no. 3 (1984)).

- ↑ Ellen Barry, To U.S. in '70s, a Dissenting Diplomat. To Bangladesh, 'a True Friend.'", The New York Times (June 27, 2016).

- 1 2 Stephen Engleberg, U.S. Says Envoy to Ireland Wrongly Punished 2 Colleagues, The New York Times (March 8, 1996).

- ↑ Richard Gilbert, Dissent in Dublin – For 2 FSOs, Cable Drew Retribution And Frustration, Foreign Service Journal (July 1996).

- ↑ Ann Wright, "America and the World" in America & The World: The Double Bind (eds. Majid Tehranian & Kevin P. Clements: Transaction Publishers, 2005), pp. 93–94.

- ↑ John Brady Kiesling, Diplomacy Lessons: Realism for an Unloved Superpower (Potomac Books, 2006), appendix B.

- 1 2 3 "Former U.S. Diplomat Weighs In On State Department Dissent Cable". All Things Considered. NPR. February 1, 2017.

- ↑ Peter Slevin, Diplomats Honored for Dissent: Envoys Challenged Bush Foreign Policy, The Washington Post (June 28, 2004), A19.

- 1 2 3 Max Fisher, The State Department's Dissent Memo on Syria: An Explanation, The New York Times (June 22, 2016).

- ↑ Jeffrey Gettleman (January 31, 2017). "State Dept. Dissent Cable on Trump's Ban Draws 1,000 Signatures". The New York Times.

- ↑ Felicia Schwartz (February 1, 2017). "State Department Dissent, Believed Largest Ever, Formally Lodged". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Steven Rosefielde, Russia in the 21st Century: The Prodigal Superpower (Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 212–13.

- ↑ "Constructive Dissent Awards". www.afsa.org. American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- ↑ "Dissent Channel". www.afsa.org. American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- ↑ Zamora, Francisco (2012). "Dissent: USAID's New Direct Channel". Foreign Service Journal. 89 (1): 50.

External links

- American Foreign Service Association's guide to use of the Dissent Channel

- 2 FAM 070 – the portion of the Foreign Affairs Manual pertaining to use and management of the Dissent Channel