Dislocated shoulder

| Dislocated shoulder | |

|---|---|

| |

| The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | S43.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 831 |

| DiseasesDB | 31231 |

| eMedicine | orthoped/440 radio/630 sports/152 |

| MeSH | D012783 |

A dislocated shoulder occurs when the humerus separates from the scapula at the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint). The shoulder joint has the greatest range of motion of any joint, at the cost of low joint stability, and it is therefore particularly susceptible to subluxation (partial dislocation) and dislocation.[1] Approximately half of major joint dislocations seen in emergency departments involve the shoulder.

Signs and symptoms

- Significant pain, sometimes felt along the arm past the shoulder.

- Inability to move the arm from its current position, particularly in positions with the arm reaching away from the body and with the top of the arm twisted toward the back.

- Numbness of the arm.

- Visibly displaced shoulder. Some dislocations result in the shoulder appearing unusually square.

- No palpable bone on the side of the shoulder.

Diagnosis

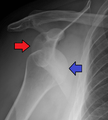

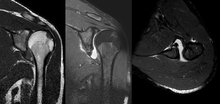

A diagnosis of shoulder dislocation is often suspected based on patient history and physical examination. Radiographs are made to confirm the diagnosis. Most dislocations are apparent on radiographs showing incongruence of the glenohumeral joint. Posterior dislocations may be hard to detect on standard AP radiographs, but are more readily detected on other views. After reduction, radiographs are usually repeated to confirm successful reduction and to detect bony damage. After repeated shoulder dislocations, an MRI scan may be used to assess soft tissue damage. In regards to recurrent dislocations, the supine apprehension test is a useful test in determining athletes who are predisposed to future dislocations.

There are three main types of dislocations: anterior, posterior, and inferior.

Anterior (forward)

In over 95% of shoulder dislocations, the humerus is displaced anteriorly. In most of those, the head of the humerus comes to rest under the coracoid process, referred to as sub-coracoid dislocation. Sub-glenoid, subclavicular, and, very rarely, intrathoracic or retroperitoneal dislocations may also occur.[2]

Anterior dislocations are usually caused by a direct blow to, or fall on, an outstretched arm. The patient typically holds his/her arm externally rotated and slightly abducted.

Damage to the axillary artery[3] and axillary nerve (C5,C6) may result. The axillary nerve is injured in 37% making it the most commonly injured structure with this type of injury.[4] Other common, associated, nerve injuries include injury to the suprascapular nerve (29%) and the radial nerve (22%).[4] Axillary nerve damage results in a weakened or paralyzed deltoid muscle and as the deltoid atrophies unilaterally, the normal rounded contour of the shoulder is lost. A patient with injury to the axillary nerve will have difficulty in abducting the arm from approximately 15° away from the body. The supraspinatus muscle initiates abduction from a fully adducted position.

- An anterior dislocation of the shoulder

Anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. AP X ray

Anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. AP X ray Anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. Y view X ray.

Anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. Y view X ray.

Posterior (backward)

Posterior dislocations are occasionally due to the muscle contraction from electric shock or seizure and may be caused by strength imbalance of the rotator cuff muscles. Patients typically present holding their arm internally rotated and adducted, and exhibiting flattening of the anterior shoulder with a prominent coracoid process.

Posterior dislocations may go unrecognized, especially in an elderly patient[5] and in the unconscious trauma patient.[6] An average interval of 1 year was noted between injury and diagnosis in a series of 40 patients.[7]

Inferior (downward)

Inferior dislocation is the least likely, occurring in less than 1%. This condition is also called luxatio erecta because the arm appears to be permanently held upward or behind the head.[8] It is caused by a hyper abduction of the arm that forces the humeral head against the acromion. Such injuries have a high complication rate as many vascular, neurological, tendon, and ligament injuries are likely to occur from this mechanism of injury.

Treatment

Prompt medical treatment should be sought for suspected dislocation. Usually, the shoulder is kept in its current position by use of a splint or sling (however, see below). A pillow between the arm and torso may provide support and increase comfort. Strong analgesics are needed to allay the pain of a dislocation and the distress associated with it.

Reduction

Emergency department care is focused on returning the shoulder to its normal position, a process known as reduction. Normally, closed reduction, in which the relationship of bone and joint is manipulated externally without surgical intervention, is used. A variety of techniques exist, but some are preferred due to fewer complications or easier execution.[9] In cases where closed reduction is not successful, open, surgical, reduction may be needed.[10] Following reduction, x-ray is often used to confirm success and absence of associated fractures. The arm should be kept in a sling or immobilizer for several days, prior to supervised recovery of motion and strength.

Traditional reduction techniques such as Hippocrates' and Kocher's are rarely used anymore. The traditional 'Hippocratic Reduction' placed the operator's heel in the person's armpit while traction was applied to their arm. Kocher's method, if performed slowly, can be performed without anesthesia. Traction is applied to the arm which is carefully adducted (brought to the mid-line). It is then externally rotated and the arm abducted (brought away from the mid-line) following which it is internally rotated and maintained in position with the help of a sling. Some avoid this technique because of the possibility of neurovascular complications and proximal humerus fracture.

A variety of non-operative reduction techniques are employed. They have certain principles in common including gentle in-line traction, reduction or abolition of muscle spasm, and gentle external rotation. They all strive to avoid inadvertent injury. Two of them, the Milch and Stimson techniques, have been compared in randomized trial.[11] These techniques include:

- External rotation: The person's arm is adducted (brought against a person's side). The elbow is than bent to 90 degrees and the forearm is slowly and gently externally rotated. Any discomfort or spasm interrupts the process until the person is able to relax. Reduction usually takes place by the time full external rotation has been achieved;[12]

- Milch: This is an extension of the external rotation technique. The externally rotated arm is gently abducted (brought away from the body into an overhead position) while external rotation is maintained. Gentle in-line traction is applied to the humerus while some pressure is applied to the humeral head via the operator's thumb in the armput;[13]

An example of Stimson maneuver. Person is lying on their stomach with a 4 kg weight tied to their wrist.

An example of Stimson maneuver. Person is lying on their stomach with a 4 kg weight tied to their wrist. - Prone or Stimson: The person lies on their stomach on a bed or bench and the arm hangs off the side, being allowed to drop toward the ground. A 5–10 kg weight is suspended from the wrist to overcome spasm and to permit reduction by the force of gravity;[11]

- Spaso: The person is on their back and gentle upward traction is applied to the extremity coupled with external rotation;[14]

- Cunningham technique: The operator is seated in front of the person who is in a comfortable sitting position. The patient places the hand of the dislocated extremity on the operator's shoulder who then rests one arm on the person's elbow crease while gently massaging the patient's biceps, deltoid, and trapezius to promote relaxation. The patient is then encouraged to pull the shoulder blades together while straightening the back. This moves the scapulae medially towards the spine thereby removing a major obstacle that might prevent reduction of the humeral head.[15]

- FARES method (fast, reliable, and safe): With the person lying on their back, the operator holds the person's hand on the affected side while the arm is at the side and the elbow is fully extended. The forearm in neutral position. Next, the operator gently applies longitudinal traction and slowly the arm is abducted. At the same time, continuous vertical oscillating movement at a rate of 2-3 "cycles" per second is applied throughout the whole reduction process.[16][17]

Post-reduction

There does not appear to be any difference in outcomes when the arm is immobilized in internal versus external rotation following an anterior shoulder dislocation.[18][19]

A 2008 study of 300 people for almost six years found that conventional shoulder immobilisation in a sling offered no benefit.[20]

Non-operative

Rotator cuff and deltoid strengthening has long been the focus of conservative treatment for the unstable shoulder and in many cases is advocated as a substitute for surgical stabilization. In multidirectional instability patients who have experienced atraumatic subluxation or dislocation events, cohort studies demonstrate good responses to long-term progressive resistance exercises if judged according to function, pain, stability, and motion scores.[21] However, in those experiencing a discrete traumatic dislocation event, responses to non-operative treatment are less than satisfactory, a pattern that inspired the Matsen and Harryman classification of shoulder instability, TUBS (traumatic, unidirectional, Bankart, and usually requiring surgery) and AMBRI (atraumatic, multidirectional, bilateral, rehabilitation, and occasionally requiring an inferior capsular shift).[22] It is thought that traumatic dislocations, as opposed to atraumatic dislocations and instability events, result in a higher incidence of capsuloligamentous injuries that disturb normal anatomy and leave shoulders too structurally compromised to respond to conservative treatment. Pathoanatomic studies of those sustaining a first-time traumatic anterior dislocation and subluxation reveal a high rate of labral lesions including the important injury, in structural terms, to the glenohumeral ligament in the inferior part of the labrum, known as the Bankart lesion.[23]

Surgery

A systematic review of published literature concerning dislocation of the shoulder has indicated that young adults engaged in highly demanding sports or job activities should be considered for operative intervention to achieve optimal outcome.[24] Arthroscopic surgery techniques may be used to repair the glenoidal labrum, capsular ligaments, biceps long head anchor or SLAP lesion and/or to tighten the shoulder capsule.[25]

Arthroscopic stabilization surgery has evolved from the Bankart repair, a time-honored surgical treatment for recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder.[26] However, the failure rate following Bankart repair has been shown to increase markedly in patients with significant bone loss from the glenoid (socket).[27] In such cases, improved results have been reported with some form of bone augmentation of the glenoid such as the Latarjet operation.[28][29]

Although posterior dislocation is much less common, instability following it is no less challenging and, again, some form of bone augmentation may be required to control instability.[30]

There remains those situations characterized by multidirectional instability, which have failed to respond satisfactorily to rehabilitation, falling under the AMBRI classification previously noted. This is usually due to an overstretched and redundant capsule which no longer offers stability or support. Traditionally, this has responded well to a 'reefing' procedure known as inferior capsular shift.[31] More recently, the procedure has been carried out as an arthroscopic procedure, rather than open surgery, again with comparable results.[31] Most recently, the procedure has been carried out using radio frequency technology to shrink the redundant shoulder capsule, although the long-term results of this development are currently unproven.[32]

Prognosis

After an anterior shoulder dislocation, the risk of a future dislocation is about 20%. This risk is greater in males than females.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ Good, CR; MacGillivray, JD (February 2005). "Traumatic shoulder dislocation in the adolescent athlete: Advances in surgical treatment". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 17 (1): 25–9. PMID 15659959. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000147905.92602.bb.

- ↑ Shoulder Dislocations at eMedicine

- ↑ Kelley, SP; Hinsche, AF; Hossain, JF (November 2004). "Axillary artery transection following anterior shoulder dislocation: Classical presentation and current concepts". Injury. 35 (11): 1128–32. PMID 15488503. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2003.08.009.

- 1 2 Malik, S; Chiampas, G; Leonard, H (November 2010). "Emergent evaluation of injuries to the shoulder, clavicle, and humerus". Emerg Med Clin North Am. 28 (4): 739–63. PMID 20971390. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2010.06.006.

- ↑ Dislocations, Shoulder at eMedicine

- ↑ Life in the Fast Lane Posterior Shoulder Dislocation Archived January 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hawkins, RJ; Neer, CS; Pianta, RM; Mendoza, FX (January 1987). "Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 69 (1): 9–18. PMID 3805075.

- ↑ Dislocations, Shoulder~clinical at eMedicine

- ↑ Dislocations, Shoulder~workup at eMedicine

- ↑ Dislocated shoulder: Treatment – MayoClinic.com

- 1 2 Amar, E; Maman, E; Khashan, M; Kauffman, E; et al. (Nov 2012). "Milch versus Stimson technique for nonsedated reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation: a prospective randomized trial and analysis of factors affecting success". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 21 (11): 1443–9. PMID 22516569. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.004.

- ↑ Harnroongroj, T; Wangphanich, J; Harnroongroj, T (Dec 2011). "Efficacy of gentle traction, abduction and external rotation maneuver under sedative-free for reduction of acute anterior shoulder dislocation: retrospective comparative study". J Med Assoc Thai. 94 (12): 1482–6. PMID 22295736.

- ↑ Singh, S; Yong, CK; Mariapan, S (Dec 2012). "Closed reduction techniques in acute anterior shoulder dislocation: modified Milch technique compared with traction-countertraction technique". J Shoulder Elbow Sur. 21 (12): 1706–11. PMID 22819577. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.04.004.

- ↑ Ugras AA, Mahirogullari M, Kural C, Erturk AH, Cakmak S (May 2008). "Reduction of anterior shoulder dislocations by Spaso technique: clinical results". J Emerg Med. 34 (4): 383–7. PMID 18226873. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.07.026.

- ↑ Walsh R, Harper H, McGrane O, Kang C (Feb 2012). "Too good to be true? Our experience with the Cunningham method of dislocated shoulder reduction". Am J Emerg Med. 30 (2): 376–7. PMID 22100465. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2011.09.016.

- ↑ Sayegh, Fares E.; Kenanidis, Eustathios I.; Papavasiliou, Kyriakos A.; Potoupnis, Michael E.; Kirkos, John M.; Kapetanos, George A. (2009-12-01). "Reduction of acute anterior dislocations: a prospective randomized study comparing a new technique with the Hippocratic and Kocher methods". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 91 (12): 2775–2782. ISSN 1535-1386. PMID 19952238. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.01434.

- ↑ "FARES method to reduce acute anterior shoulder dislocation: a case series and an efficacy analysis". Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. January 2012.

- ↑ Whelan, DB; Kletke, SN; Schemitsch, G; Chahal, J (26 June 2015). "Immobilization in External Rotation Versus Internal Rotation After Primary Anterior Shoulder Dislocation: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.". The American journal of sports medicine. 44: 521–532. PMID 26116355. doi:10.1177/0363546515585119.

- ↑ Hanchard, NC; Goodchild, LM; Kottam, L (30 April 2014). "Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 4: CD004962. PMID 24782346. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004962.pub3.

- ↑ Chalidis B, Sachinis N, Dimitriou C, Papadopoulos P, Samoladas E, Pournaras J (June 2007). "Has the management of shoulder dislocation changed over time?". Int Orthop. 31 (3): 385–9. PMC 2267594

. PMID 16909255. doi:10.1007/s00264-006-0183-y.

. PMID 16909255. doi:10.1007/s00264-006-0183-y. - ↑ Burkhead, WZ, Jr; Rockwood, CA, Jr (1992). "Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 74 (6): 890–6. PMID 1634579.

- ↑ Matsen Fa, 3rd; Harryman Dt, 2nd; Sidles, JA (1991). "Mechanics of glenohumeral instability". Clinics in sports medicine. 10 (4): 783–8. PMID 1934096.

- ↑ Owens, BD; Nelson, BJ; Duffey, ML; Mountcastle, SB; et al. (2010). "Pathoanatomy of First-Time, Traumatic, Anterior Glenohumeral Subluxation Events". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 92 (7): 1605–11. PMID 20595566. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00851.

- ↑ Longo UG, Loppini M, Rizzello G, Ciuffreda M, Maffulli N, Denaro V (Apr 2014). "Management of Primary Acute Anterior Shoulder Dislocation: Systematic Review and Quantitative Synthesis of the Literature". Arthroscopy. 30 (4): 506–22. PMID 24680311. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.01.003.

- ↑ Considering surgery – Arthroscopic shoulder surgery for dislocation, subluxation, and instability: why, when and how it is done

- ↑ "Bankart repair for unstable dislocating shoulders:". University of Washington: Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine.

- ↑ Burkhart, SS; De Beer, JF (Oct 2000). "Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion". Arthroscopy. 16 (7): 677–94. PMID 11027751. doi:10.1053/jars.2000.17715.

- ↑ Burkhart SS, De Beer JF, Barth JR, Cresswell T, Roberts C, Richards DP (Oct 2007). "Results of modified Latarjet reconstruction in patients with anteroinferior instability and significant bone loss". Arthroscopy. 23 (10): 1033–41. PMID 17916467. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.009.

- ↑ Noonan B, Hollister SJ, Sekiya JK, Bedi A (Aug 2014). "Comparison of reconstructive procedures for glenoid bone loss associated with recurrent anterior shoulder instability". J Shoulder Elbow Sur. 23 (8): 1113–9. PMID 24561175. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.011.

- ↑ Millett PJ, Schoenahl JY, Register B, Gaskill TR, van Deurzen DF, Martetschläger F (Feb 2013). "Reconstruction of posterior glenoid deficiency using distal tibial osteoarticular allograft". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 21 (2): 445–9. PMID 23114865. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2254-5.

- 1 2 Fleega, BA; El Shewy, MT (May 2012). "Arthroscopic inferior capsular shift: long-term follow-up". Am J Sports Med. 40 (5): 1126–32. PMID 22437281. doi:10.1177/0363546512438509.

- ↑ Mohtadi NG, Kirkley A, Hollinshead RM, McCormack R, MacDonald PB, Chan DS, Sasyniuk TM, Fick GH, Paolucci EO (Aug 2014). "Electrothermal arthroscopic capsulorrhaphy: old technology, new evidence. A multicenter randomized clinical trial". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 23 (8): 1171–80. PMID 24939380. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.022.

- ↑ Wasserstein, DN; Sheth, U; Colbenson, K; Henry, PD; Chahal, J; Dwyer, T; Kuhn, JE (December 2016). "The True Recurrence Rate and Factors Predicting Recurrent Instability After Nonsurgical Management of Traumatic Primary Anterior Shoulder Dislocation: A Systematic Review.". Arthroscopy. 32 (12): 2616–2625. PMID 27487737.

External links

- Imaging Shoulder Dislocation Radiology Diagnosis