Discrete spectrum

2) and a continuous part (such as the bands labeled H

2O).

A physical quantity is said to have a discrete spectrum if it takes only distinct values, with positive gaps between one value and the next.

The classical example of discrete spectrum (for which the term was first used) is the characteristic set of discrete spectral lines seen in the emission spectrum and absorption spectrum of isolated atoms of a chemical element, which only absorb and emit light at particular wavelengths. The technique of spectroscopy is based on this phenomenon.

Discrete spectra are contrasted with the continuous spectra also seen in such experiments, for example in thermal emission, in synchrotron radiation, and many other light-producing phenomena.

Discrete spectra are seen in many other phenomena, such as vibrating strings, microwaves in a metal cavity, sound waves in a pulsating star, and resonances in high-energy particle physics.

The general phenomenon of discrete spectra in physical systems can be mathematically modeled with tools of functional analysis, specifically by the decomposition of the spectrum of a linear operator acting on a functional space.

Origins of discrete spectra

Classical mechanics

In classical mechanics, discrete spectra are often associated to waves and oscillations in a bounded object or domain. Mathematically they can be identified with the eigenvalues of differential operators that describe the evolution of some continuous variable (such as strain or pressure) as a function of time and/or space.

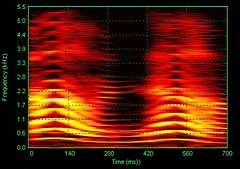

Discrete spectra are also produced by some non-linear oscillators where the relevant quantity has a non-sinusoidal waveform. Notable examples are the sound produced by the vocal chords of mammals.[1][2]:p.684 and the stridulation organs of crickets,[3] whose spectrum shows a series of strong lines at frequencies that are integer multiples (harmonics) of the oscillation frequency.

A related phenomenon is the appearance of strong harmonics when a sinusoidal signal (which has the ultimate "discrete spectrum", consisting of a single spectral line) is modified by a non-linear filter; for example, when a pure tone is played through an overloaded amplifier,[4] or when an intense monochromatic laser beam goes through a non-linear medium.[5] In the latter case, if two arbitrary sinusoidal signals with frequencies f and g are processed together, the output signal will generally have spectral lines at frequencies |mf + ng| where m and n are any integers.

Quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, the discrete spectrum of an observable corresponds to the eigenvalues of the operator used to model that observable. According to the mathematical theory of such operators, its eigenvalues are a discrete set of isolated points, which may be either finite or countable.

Discrete spectra are usually associated with systems that are bound in some sense (mathematically, confined to a compact space). The position and momentum operators have continuous spectra in an infinite domain, but a discrete (quantized) spectrum in a compact domain [6] and the same properties of spectra hold for angular momentum, Hamiltonians and other operators of quantum systems.[6]

The quantum harmonic oscillator and the hydrogen atom are examples of physical systems in which the Hamiltonian has a discrete spectrum. In the case of the hydrogen atom the spectrum has both a continuous and a discrete part, the continuous part representing the ionization.

See also

- Band structure

- Discrete frequency domain

- Decomposition of spectrum (functional analysis)

- Essential spectrum

References

- ↑ Hannu Pulakka (2005), Analysis of human voice production using inverse filtering, high-speed imaging, and electroglottography. Master's thesis, Helsinki University of Technology.

- ↑ Björn Lindblom and Johan Sundberg (2007), The Human Voice in Speech and Singing. in Springer Handbook of Acoustics, pages 669-712. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30425-0_16 ISBN 978-0-387-30446-5

- ↑ A. V. Popov, V. F. Shuvalov, A. M. Markovich (1976), The spectrum of the calling signals, phonotaxis, and the auditory system in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, volume 7, issue 1, pages 56-62 doi:10.1007/BF01148749

- ↑ Paul V. Klipsch (1969), Modulation distortion in loudspeakers Journal of the Audio Engineering Society.

- ↑ J. A. Armstrong, N. Bloembergen J. Ducuing, and P. S. Pershan (1962), Interactions between Light Waves in a Nonlinear Dielectric. Physics Review, volume 127, issue 6, pages 1918–1939. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.127.1918

- 1 2 L. D. Landau, E. M. Lifshitz, Quantum Mechanics ( Volume 3 of A Course of Theoretical Physics ) Pergamon Press 1965