Passive transport

Passive transport is a movement of ions and other atomic or molecular substances across cell membranes without need of energy input. Unlike active transport, it does not require an input of cellular energy because it is instead driven by the tendency of the system to grow in entropy. The rate of passive transport depends on the permeability of the cell membrane, which, in turn, depends on the organization and characteristics of the membrane lipids and proteins. The four main kinds of passive transport are simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, filtration, and osmosis.

Diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of material from an area of high concentration to an area with lower concentration. The difference of concentration between the two areas is often termed as the concentration gradient, and diffusion will continue until this gradient has been eliminated. Since diffusion moves materials from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration, it is described as moving solutes "down the concentration gradient" (compared with active transport, which often moves material from area of low concentration to area of higher concentration, and therefore referred to as moving the material "against the concentration gradient"). However, in many cases (e.g. passive drug transport) the driving force of passive transport can not be simplified to the concentration gradient. If there are different solutions at the two sides of the membrane with different equilibrium solubility of the drug, the difference in degree of saturation is the driving force of passive membrane transport.[1] It is also true for supersaturated solutions which are more and more important owing to the spreading of the application of amorphous solid dispersions for drug bioavailability enhancement.

Simple diffusion and osmosis are in some ways similar. Simple diffusion is the passive movement of solute from a high concentration to a lower concentration until the concentration of the solute is uniform throughout and reaches equilibrium. Osmosis is much like simple diffusion but it specifically describes the movement of water (not the solute) across a selectively permeable membrane until there is an equal concentration of water and solute on both sides of the membrane. Simple diffusion and osmosis are both forms of passive transport and require none of the cell's ATP energy.

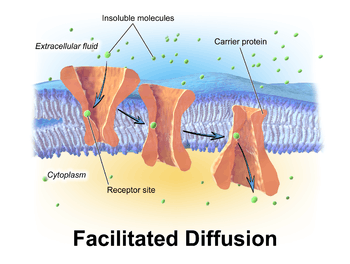

Facilitated diffusion

Facilitated diffusion, also called carrier-mediated osmosis, is the movement of molecules across the cell membrane via special transport proteins that are embedded within the cellular membrane. Large, insoluble molecules, such as glucose, vesicles and proteins require a carrier molecule to move through the plasma membrane.[2] Therefore, it will bind with its specific carrier proteins, and the complex will then be bonded to a receptor site and moved through the cellular membrane. Facilitated diffusion is a passive process: the solutes move down their concentration gradient and do not require the expenditure of cellular energy for this process. Carrier proteins and channel proteins allow for the diffusion of molecules across the cell membrane. Carrier proteins undergo conformational alterations to allow molecules to pass, while channel proteins form unblocked pores.[3]

Facilitated diffusion may be achieved as a consequence of charge gradients in addition to concentration gradients. Plant cells create an unequal distribution of charge across their plasma membrane by actively taking up or excluding ions. Active transport of protons by H+ ATPases[4] alters membrane potential allowing for facilitated passive transport of particular ions such as Potassium [5] down their charge gradient through high affinity transporters and channels.

Filtration

Filtration is movement of water and solute molecules across the cell membrane due to hydrostatic pressure generated by the cardiovascular system. Depending on the size of the membrane pores, only solutes of a certain size may pass through it. For example, the membrane pores of the Bowman's capsule in the kidneys are very small, and only albumins, the smallest of the proteins, have any chance of being filtered through. On the other hand, the membrane pores of liver cells are extremely large,but not forgetting cells are extremely small to allow a variety of solutes to pass through and be metabolized.

Osmosis

Osmosis is the movement of water molecules across a selectively permeable membrane. The net movement of water molecules through a partially permeable membrane from a solution of high water potential to an area of low water potential. A cell with a less negative water potential will draw in water but this depends on other factors as well such as solute potential (pressure in the cell e.g. solute molecules) and pressure potential (external pressure e.g. cell wall). There are three types of Osmosis solutions: the isotonic solution, hypotonic solution, and hypertonic solution. Isotonic solution is when the extracellular solute concentration is balanced with the concentration inside the cell. In the Isotonic solution, the water molecules still moves between the solutions, but the rates are the same from both directions, thus the water movement is balanced between the inside of the cell as well as the outside of the cell. A hypotonic solution is when the solute concentration outside the cell is lower than the concentration inside the cell. In hypotonic solutions, the water moves into the cell, down its concentration gradient (from higher to lower water concentrations). That can cause the cell to swell. Cells that don't have a cell wall, such as animal cells, could burst in this solution. A hypertonic solution is when the solute concentration is higher (think of hyper - as high) than the concentration inside the cell. In hypertonic solution, the water will move out, causing the cell to shrink.

See also

References

- ↑ Borbas, E.; et al. (2016). "Investigation and Mathematical Description of the Real Driving Force of Passive Transport of Drug Molecules from Supersaturated Solutions". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 13: 3816–3826. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00613.

- ↑ Arcizet, Delphine; Meier, Börn; Sackmann, Erich; Rädler, Joachim O.; Heinrich, Doris. "Temporal Analysis of Active and Passive Transport in Living Cells". Physical Review Letters. 101 (24). doi:10.1103/physrevlett.101.248103.

- ↑ Cooper, Geoffrey M (2000). The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc. ISBN 978-0878931064.

- ↑ Palmgren, Michael G. (2001-01-01). "PLANT PLASMA MEMBRANE H+-ATPases: Powerhouses for Nutrient Uptake". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 52 (1): 817–845. PMID 11337417. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.817.

- ↑ Dreyer, Ingo; Uozumi, Nobuyuki (2011-11-01). "Potassium channels in plant cells". FEBS Journal. 278 (22): 4293–4303. ISSN 1742-4658. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08371.x.

- Alcamo, I. Edward (1997). "Chapter 2–5: Passive transport". Biology coloring workbook. Illustrations by John Bergdahl. New York: Random House. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780679778844.

- Sadava, David; H. Craig Heller; Gordon H. Orians; William K. Purves; David M. Hillis (2007). "What are the passive processes of membrane transport?". Life : the science of biology (8th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. pp. 105–110. ISBN 9780716776710.

- Srivastava, P. K. (2005). Elementary biophysics : an introduction. Harrow: Alpha Science Internat. pp. 140–148. ISBN 9781842651933.