Hindi Belt

| Hindi Belt | |

|---|---|

|

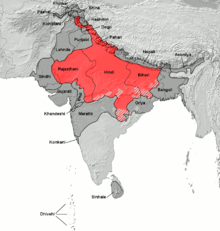

The Hindi Belt in red | |

| Native to | Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand[1] |

| Ethnicity | Awadhis, Bhojpuris, Marwaris, etc.. |

Native speakers |

422 million (2001)[2][3] L2 speakers: 98 million (2001)[3] |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects | |

|

Devanagari for Hindi Braille (Hindi Braille) Kaithi (historical) Latin script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

hi, ur |

| ISO 639-2 |

hin, urd, awa, bho, mag, mwr |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously:hin – Hindiurd – Urdubgc – Haryanvibjj – Kanaujibns – Bundeliawa – Awadhibho – Bhojpurihne – Chhattisgarhibfy – Baghelihns – Caribbean Hindustanihif – Fiji Hindimag – Magahisck – Sadrimwr – Marwarimup – Malvilmn – Lambadihoj – Hadothi, Harotigdx – Godwaribgq – Bagrigbm – Garhwalikfy – Kumaonixnr – Kangri |

The Hindi Belt or Hindi Heartland is a loosely defined linguistic region in north-central India where varieties of Hindi in the broadest sense are widely spoken.[7][8][9] It is sometimes also used to refer to those Indian states whose official language is Hindi and have a Hindi-speaking majority, namely Bihar, Chandigarh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh.

Hindi as a dialect continuum

Hindi, in the broad sense, is that part of the Indo-Aryan dialect continuum that lies within the cultural Hindi Belt in the northern plains of India. In the words of Masica (1991), these [languages] are the so-called regional languages of the Hindi area, sometimes less accurately called Hindi "dialects". Hindi in this broad sense is an ethnic rather than a linguistic concept.

This broad definition of Hindi is one of the ones used in the Indian census, and results in a clear majority of Indians being reported to be speakers of Hindi, though Hindi-area respondents vary as to whether they call their language Hindi or use a local language name. As defined in the 1991 census, Hindi has a broad and a narrow sense. The name "Hindi" is thus ambiguous.

The broad sense covers a number of Central, East-Central, Eastern, and Northern Zone languages, including the Bihari languages except Maithili, all the Rajasthani languages, and the Pahari languages except Western Pahari and Nepali. This is an area bounded on the west by Punjabi and Sindhi; on the south by Gujarati, Marathi, and Odia; on the east by Maithili and Bengali; and on the north by Nepali, Kashmiri, and Tibetic languages. Linguistically, the varieties of this belt can be considered separate languages rather than dialects of a single language.

In the narrow sense, the Hindi languages proper, Hindi can be equated with the Central Zone Indic languages. These are conventionally divided into Western Hindi and Eastern Hindi. An even narrower definition of Hindi is that of the official language, Modern Standard Hindi or Manak Hindi, a standardised register of Hindustani, one of the varieties of Western Hindi. Standardised Hindustani—including both Manak Hindi and Urdu—is historically based on the Khariboli dialect of 17th-century Delhi.

Number of speakers

Population data from the 16th (2009) edition of Ethnologue is as follows, counting languages with two million or more speakers:

- Central zone (Hindi proper)

- Western Hindi (West Central zone)

- 240 M Hindustani excluding Urdu (numbers out of date)

- 13 M Haryanvi (numbers out of date)

- 10 M Kanauji

- 20 M Bundeli

- Eastern Hindi (East Central zone)

- 38 M Awadhi

- 18 M Chhattisgarhi

- 8 M Bagheli

- Western Hindi (West Central zone)

- Bihari languages apart from Maithili (part of Eastern zone, which also includes Bengali and Odia)

- Rajasthani (part of Western Zone, which also includes Gujarati and Bhili) Today Sahitya Akademi, National Academy of Letters and University Grants Commission recognise Rajasthani as a distinct language.

- Central Pahari (part of Northern zone, which also includes Nepali)

According to the 2001 Indian census,[10] 258 million people in India (25% of the population) regarded their native language to be "Hindi", however, including other Hindi dialects this figure becomes 422 million Hindi speakers (41% of the population). These figures do not count 52 million Indians who considered their mother tongue to be "Urdu". The numbers are also not directly comparable to the table above; for example, while independent estimates in 2001 counted 37 million speakers of Awadhi,[11] in the 2001 census only 2½ million of these identified their language as "Awadhi" rather than as "Hindi".

Outside the Indian subcontinent

Much of the Hindi spoken outside of the subcontinent is quite distinct from the Indian standard language. Most Pakistani speakers, and some Muslim Indian speakers, call their version of Hindustani "Urdu" rather than "Hindi" or "Hindustani". Religious proponents both of Hindi and of Urdu often contend that they are two separate languages despite their mutual intelligibility.

Mauritian Hindi is spoken in Mauritius. It is based on Bhojpuri and influenced by French. Sarnami is a form of Bhojpuri with Awadhi influence. It spoken by Surinamese of Indian descent. Fiji Hindi is a derived form of Awadhi, Bhojpuri and including some English and very few native Fijian words. It is spoken by Fijians of Indian descent. Trinidad Hindi is based on Bhojpuri and is spoken in Trinidad and Tobago by people of Indian descent. South African Hindi is based on Bhojpuri and is spoken in South Africa by people of Indian descent.

Geography and demography

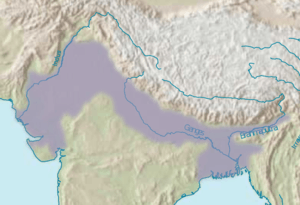

The highly fertile, flat, alluvial Gangetic plain occupies the northern portion of the Hindi Heartland, the Vindhyas in Madhya Pradesh demarcate the southern boundary and the hills and dense forests of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh lie in the east. The region has a predominantly subtropical climate, with cool winters, hot summers and moderate monsoons. The climate does vary with latitude somewhat, with winters getting cooler and rainfall decreasing. It can vary significantly with altitude, especially in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

The Hindi Heartland supports about a third of India's population and occupies about a quarter of its geographical area. The population is concentrated along the fertile Ganges plain in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Bihar.

Although the vast majority of the population is rural, significant urban cities include Chandigarh, Panchkula, Delhi, Lucknow, Kanpur, Allahabad, Jaipur, Agra, Varanasi, Indore, Bhopal, Patna, Jamshedpur and Ranchi. The region hosts a diverse population, with various dialects of Hindi being spoken along with other Indian languages, and multi-religious population including Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs along with people from various castes and a significant tribal population. The geography is also varied, with the flat, alluvial Gangetic plain occupying the northern portion, the Vindhyas in Madhya Pradesh demarcating the southern boundary and the hills and dense forests of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh separate the region from West Bengal and Odisha.

Political sphere

Over years political development in some of these states are dominated by caste based politics. In several parts, upper caste people had a disproportionate hold on political life. But this trend has changed in recent years.[12]

Bibliography

- Grierson, G. A. Linguistic Survey of India Vol I-XI, Calcutta, 1928, ISBN 81-85395-27-6

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2003), "Hindi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh, The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 250–285, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

Notes

- ↑ Some languages may be over- or underrepresented as the census data used is at the state-level. For example, while Urdu has 52 million speakers (2001), in no state is it a majority as the language itself is primarily limited to Indian Muslims.

References

- ↑ "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ ORGI. "Census of India: Comparative speaker's strength of Scheduled Languages-1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001".

- 1 2 S, Rukmini. "Sanskrit and English: there’s no competition".

- ↑

- 1 2 3

- ↑ "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ B.L. Sukhwal (1985), Modern Political Geography of India, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division,

... In the Hindi heartland ...

- ↑ Stuart Allan, Barbie Zelizer (2004), Reporting war: journalism in wartime, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-33998-7,

... located in what is called the "Hindi heartland" or the "Hindi belt" of north and central India ...

- ↑ B.S. Kesavan (1997), Origins of printing and publishing in the Hindi heartland (Volume 3 of History of printing and publishing in India : a story of cultural re-awakening), National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-2120-X

- ↑ Census of India Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ USCWM

- ↑ Jaffrelot, Christophe (1 January 2000). "The Rise of the Other Backward Classes in the Hindi Belt". The Journal of Asian Studies. 59 (1): 86–108. JSTOR 2658585. doi:10.2307/2658585.

External links

- On The Problems Of The Hindi Belt: A Seminar

- Bhatele, Abhinav: Introduction To Hindi (Archived 1 June 2012)