HMNB Devonport

| HMNB Devonport | |

|---|---|

| Guzz | |

|

Plymouth, England | |

|

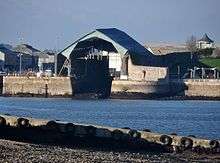

An aerial photograph of the core of HMNB Devonport with several ships alongside. The buildings in the lower half of the picture are the Fleet Accommodation Centre | |

| Type | Naval base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Royal Navy |

| Site history | |

| In use | Since the 16th century |

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | Commodore Ian Shipperley[1] |

| Garrison | Devonport Flotilla |

Her Majesty's Naval Base, Devonport (HMNB Devonport), is the largest naval base in Western Europe[2] and is the sole nuclear repair and refuelling facility for the Royal Navy.

It is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Portsmouth). HMNB Devonport is located in Devonport, in the west of the city of Plymouth, England. Having begun as Royal Navy Dockyard in the late-17th century, Shipbuilding ceased at Devonport in the early 1970s, but ship maintenance work has continued: the now privatised maintenance facilities are operated by Babcock Marine, a division of Babcock International Group, who took over the previous owner Devonport Management Limited (DML) in 2007. (DML had been running the Dockyard since privatisation, 1987.)[3]

From 1934 until the early 21st century the naval barracks on the site was named HMS Drake (it had previously been known as HMS Vivid after the base ship of the same name). Recently, the name HMS Drake (and, more to the point, its command structure) has been extended to cover the entire base; the barracks buildings are now termed the Fleet Accommodation Centre.[4] In the early 1970s the newly-styled 'Fleet Maintenance Base' was itself commissioned as HMS Defiance; it remained so until 1994, at which point it was amalgamated into HMS Drake.

HM Naval Base Devonport is the home port of the Devonport Flotilla which includes the largest ship in the Royal Navy, HMS Ocean, and the Trafalgar-class submarines. In 2009 the Ministry of Defence announced the conclusion of a long-running review of the long-term role of three naval bases. Devonport will no longer be used as a base for attack submarines after these move to Faslane by 2017, and the Type 45 destroyers are based at Portsmouth. However, Devonport retains a long-term role as the dedicated home of the amphibious fleet, survey vessels and half the frigate fleet.[5]

History

In 1588, the ships of the English Navy set sail for the Spanish Armada through the mouth of the River Plym, thereby establishing the military presence in Plymouth. Sir Francis Drake is now an enduring legacy in Devonport, as the naval base has been named HMS Drake.[2]

Origins

In 1689 Prince William of Orange became William III and almost immediately he required the building of a new Royal Dockyard west of Portsmouth. Edmund Dummer, Surveyor of the Navy, travelled the West Country searching for an area where a dockyard could be built; he sent in two estimates for sites, one in Plymouth, Cattewater and one further along the coast, on the Hamoaze, a section of the River Tamar, in the parish of Stoke Damerel. Having dismissed the Plymouth site as inadequate, he settled on the Hamoaze area which soon became known as Plymouth Dock, later renamed Devonport. On 30 December 1690, a contract was let for a dockyard to be built: the start of Plymouth (later Devonport) Royal Dockyard.[6] Having selected the location, Dummer was given responsibility for designing and building the new yard.

At the heart of his new dockyard, Dummer placed a stone-lined basin, giving access to what proved to be the first successful stepped stone dry dock in Europe.[7] Previously the Navy Board had relied upon timber as the major building material for dry docks, which resulted in high maintenance costs and was also a fire risk. The docks Dummer designed were stronger with more secure foundations and stepped sides that made it easier for men to work beneath the hull of a docked vessel. These innovations also allowed rapid erection of staging and greater workforce mobility. He discarded the earlier three-sectioned hinged gate, which was labour-intensive in operation, and replaced it with the simpler and more mobile two-sectioned gate.

Dummer wished to ensure that naval dockyards were efficient working units that maximised available space, as evidenced by the simplicity of his design layout at Plymouth Dock. He introduced a centralised storage area alongside the basin, and a logical positioning of other buildings around the yard. His double rope-house combined the previously separate tasks of spinning and laying while allowing the upper floor to be used for the repair of sails.[8] On high ground overlooking the rest of the yard he built a grand terrace of houses for the senior dockyard officers (the first known example in the country of a palace-front terrace).[9]

Most of Dummer's buildings and structures were rebuilt over ensuing years, including the basin and dry dock (today known as No. 1 Basin and No. 1 Dock).[10] The terrace survived into the 20th century, but was largely destroyed in the Blitz along with several others of Devonport's historic buildings. Just one end section of the terrace survives; dating from 1692–96, it is the earliest surviving building in any royal dockyard.[9]

Development

The dockyard was established on the southern tip of the present-day site; it then expanded northwards, in stages, over the next two-and-a-half centuries. The town that grew around the dockyard was called Plymouth Dock up to 1823, when the townspeople petitioned for it to be renamed Devonport. The dockyard followed suit twenty years later, becoming Devonport Royal Dockyard. In just under three centuries over 300 vessels were built at Devonport, the last being HMS Scylla in 1971.[11]

South Yard

The dockyard began in what is now known as the South Yard area of Devonport. It was here that Dummer built his groundbreaking stone dry dock (completely rebuilt in the 1840s).

In the 1760s a period of expansion began, leading to a configuration which (despite subsequent rebuildings) can still be seen today : five slipways, four dry docks and a wet basin (slipways were used for shipbuilding, but the main business of the eighteenth-century yard was the repair, maintenance and equipping of the fleet, for which the dry docks and basin were used).[12] One slipway (1774) survives unaltered from this period (Slip No. 1): a rare survival.[13] It is covered with a timber superstructure of 1814, a similarly rare and early survival of its type; indeed, only three such timber slip covers have survived in Britain, two of them at Devonport (the second of these, of similar vintage, stands over the former No. 5 Slip; it was later converted to house the Scrieve Board, for full-size drafting of ship designs).[14]

From the beginning, the docks and slips would have been interspersed with workshops specializing in large-scale woodwork (mast houses, shipwrights' sheds etc.). As part of the expansion of the yard in the second half of the 18th century, a new rope-making complex was built (and survives in part, albeit rebuilt following a fire in 1812, alongside the perimeter wall). At around the same time, a smithery was built (1776; though subsequently rebuilt it still stands, the earliest surviving smithery in any royal dockyard).[15] Initially used for the manufacture of anchors and smaller metal items, it would later be expanded to fashion the iron braces with which wooden hulls and decks began to be strengthened; as such, it provided a hint of the huge change in manufacturing technology that would sweep the dockyards in the nineteenth century as sail began to make way for steam, and wood for iron and steel.[12]

The most imposing building of this period, a double-quadrangular storehouse of 1761 probably designed by Thomas Slade, was destroyed in the Plymouth Blitz as were several other buildings of the 18th and early-19th century, including the long and prominent pedimented workshop with its central clocktower, built to accommodate a range of woodworkers and craftsmen, and Edward Holl's Dockyard Church of 1814.[16] Nonetheless, the South Yard alone still contains four Scheduled Ancient Monuments and over thirty listed buildings and structures[17] (though some of these have been allowed to fall into a derelict state in recent years: the 18th-century South Sawmills and South Smithery are both on the Heritage At Risk (HAR) register).[18][19]

Morice Yard (New Gun Wharf)

Provision of ships' armaments was not the responsibility of the Navy but of the independent Board of Ordnance, which already had a wharf and storage facility in the Mount Wise area of Plymouth. This, however, began to prove insufficient and in 1719 the board established a new gun wharf on land leased from one Sir Nicholas Morice, immediately to the north of the established Dockyard. The Morice Yard was a self-contained establishment with its own complex of workshops, workers, officers, offices and storehouses. Gunpowder was stored on site, which began to be a cause for concern among local residents (as was the older store in the Royal Citadel within the city of Plymouth). In time new gunpowder magazines were built further north, first at Keyham (1770s), but later (having to make way for further dockyard expansion) relocating to Bull Point (1850).[20]

In contrast to South Yard, which fared badly in the Blitz, most of the original buildings survive at Morice Yard, enclosed behind their contemporary boundary wall; over a dozen of these are listed.[17] On higher ground behind the wharf itself is a contemporary terrace of houses for officers (1720), built from stone rubble excavated during the yard's construction.[12]

Morice Ordnance Yard remained independent from the dockyard until 1941, at which point it was integrated into the larger complex.

The Devonport Lines

In 1758, the Plymouth and Portsmouth Fortifications Act provided the means to construct a permanent landward defence for the dockyard complex. The Devonport Lines were a bastion fortification which consisted of an earthen rampart with a wide ditch and a glacis. The lines ran from Morice Yard on the River Tamar, enclosing the whole dockyard and town, finally meeting the river again at Stonehouse Pool, a total distance of 2000 yards (1800 metres). There were four bastions, Marlborough Bastion to the north, Granby Bastion to the north-east, Stoke Bastion to the east and George Bastion to the south east. There were originally two gates in the lines, the Stoke Barrier at the end of Fore Street and the Stonehouse Barrier. A third gate called New Passage was created in the 1780s, giving access to the Torpoint Ferry. After 1860, the fortifications were superseded by the Palmerston Forts around Plymouth and the land occupied by the lines was either sold or utilised by the dockyard.[21]

Keyham (the North Yard)

In the mid-nineteenth century, all royal dockyards faced the challenge of responding to the advent first of steam power and then metal hulls. Those unable to expand were closed; the rest underwent a transformation through growth and mechanisation.

At Devonport, in 1864, a separate, purpose-built steam yard was opened on a self-contained site at Keyham, just to the north of Morice Yard (and a subterranean tunnel was built linking the new yard with the old). A pair of basins (8-9 acres each) were constructed: No. 2 Basin gave access to three large dry-docks, while No. 3 Basin was the frontispiece to a huge integrated manufacturing complex. This became known as the Quadrangle: it housed foundries, forges, pattern shops, boilermakers and all manner of specialized workshops. Two stationary steam engines drove line shafts and heavy machinery, and the multiple flues were drawn by a pair of prominent chimneys. The building still stands, and is Grade I listed; architectural detailing was by Sir Charles Barry. English Heritage calls it 'one of the most remarkable engineering buildings in the country'.[12] The three dry docks were rebuilt, expanded and covered over in the 1970s to serve as the Frigate Refit Centre.[3]

In 1880 a Royal Naval Engineering College was established at Keyham, housed in a new building just outside the dockyard wall alongside the Quadrangle where students (who joined at 15 years of age) gained hands-on experience of the latest naval engineering techniques. The Engineering College moved to nearby Manadon in 1958; the Jacobethan-style building then went on to house the Dockyard Technical College for a time, but was demolished in 1985.[16]

In 1895 the decision was taken to expand the Keyham Steam Yard to accommodate the increasing size of modern warships. By 1907 Keyham, now renamed the North Yard, had more than doubled in size with the addition of No. 4 and No. 5 Basins (of 10 and 35 acres respectively), linked by a very large lock-cum-dock, 730 ft in length, alongside three more dry-docks of a similar size, able to "accommodate ships larger than any war-vessel yet constructed".[22] In the 1970s the northern end of No. 5 Basin was converted to serve as a new Fleet Maintenance Base, to be built alongside a Submarine Refit Complex for nuclear submarines; an 80-ton cantilever crane, one of the largest in western Europe, was installed to lift nuclear cores from submarines in newly-built adjacent dry docks.[3]

Further north still, Weston Mill Lake (at one time Devonport's coaling yard) was converted in the 1980s to provide frigate berths for the Type 22 fleet.[23] It is now where the Navy's amphibious warfare ships are based. In 2013 a new Royal Marines base, RM Tamar, was opened alongside; as well as serving as headquarters for 1 Assault Group Royal Marines, it can accommodate marines, alongside their ships, prior to deployment.[24]

In 2011 the MOD sold the freehold of the North Yard to the Dockyard operator, Babcock; the site includes six listed buildings and structures, among them the Grade I listed Quadrangle.[25]

The naval barracks (HMS Drake)

Until the late nineteenth century, sailors whose ships were being repaired or refitted, or who were awaiting allocation to a vessel, were accommodated in floating hulks. Construction of an onshore barracks, just north-east of the North Yard, was completed in 1889 with accommodation for 2,500; sailors and officers moved in in June of that year. In 1894 a contingent of sixty Royal Navy homing pigeons was accommodated on the site.

The prominent clock tower was built in 1896, containing a clock and bell by Gillett & Johnston; it initially functioned as a semaphore tower. 1898 saw the barracks expand to accommodate a further 1,000 men. The wardroom block dates from this period. More buildings were added in the early years of the twentieth century, including St Nicholas's Church.[26] This part of the site contains some fourteen listed buildings and structures.[17]

Associated establishments nearby

Several establishments were set up in the vicinity of Devonport and Plymouth in direct relationship either to the Royal Dockyard or to Plymouth's use as a base for the Fleet, including:

- Royal Citadel, Plymouth (1665), built to defend the harbour and anchorage, currently the base of 29 Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery.

- Dockyard defences, including Devonport Lines (1758) and the later Palmerston Forts, Plymouth

- Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse (1760, closed 1995)

- Stonehouse Barracks (1779), headquarters of 3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines.

- Admiralty House, Mount Wise (1789), former headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth (together with the Second World War Combined Military Headquarters (later Plymouth Maritime Headquarters) it was decommissioned in 2004).[27]

- Plymouth Breakwater (1812)

- Royal William Victualling Yard (1835) built by the Victualling Commissioners in nearby Stonehouse for supplying the Royal Navy (closed 1992 and converted into housing).

- HMS Raleigh, RN basic training establishment, across the Hamoaze at Torpoint, Cornwall.

- RM Turnchapel, a former Royal Marines military installation (decommissioned 2014).

Today

The Royal Navy Dockyard consists of fourteen dry docks (docks numbered 1 to 15, but there is no 13 Dock),[2] four miles (6 km) of waterfront, twenty-five tidal berths, five basins and an area of 650 acres (2.6 km²). The dockyard employs 2,500 service personnel and civilians, supports circa 400 local firms and contributes approximately 10% to the income of Plymouth.[28] It is the base for the Trafalgar-class nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarines and the main refitting base for all Royal Navy nuclear submarines. Work was completed by Carillion in 2002 to build a refitting dock to support the Vanguard-class Trident missile nuclear ballistic missile submarines. Devonport serves as headquarters for the Flag Officer Sea Training, which is responsible for the training of all the ships of the Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, along with many from foreign naval services. The nuclear submarine refit base was put into special measures in 2013 by the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and it could be 2020 before enhanced monitoring ceases. Safety concerns on ageing facilities, stretched resources and increasing demand are blamed for the measures.[28]

Devonport Flotilla

Ships based at the port are known as the Devonport Flotilla. This includes the Navy's assault ships HMS Ocean, HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark. It also serves as home port to most of the hydrographic surveying fleet of the Royal Navy and seven Type 23 frigates.

Amphibious assault ships

- HMS Ocean landing platform helicopter and current fleet flagship;

- HMS Albion landing platform dock;

- HMS Bulwark landing platform dock (In extended readiness).

Type 23 frigates

Trafalgar-class submarines (No longer belong to DEVFLOT now SUBFLOT (South)

_at_Devonport_2008.jpg)

Surveying squadron

Antarctic patrol ship

Archer-class patrol vessels

Other units based at Devonport

- Flag Officer Sea Training

- Hydrographic, Meteorological & Oceanographic Training Group

- HQ Amphibious Task Group

- HMS Vivid RNR

- RM Tamar/1 Assault Group Royal Marines

- 10 Landing Craft Training Squadron

- 4 Assault Squadron

- 6 Assault Squadron

- 9 Assault Squadron

- 539 Assault Squadron

- Hasler NSRC (Naval Service Recovery Centre) & Hasler Company Royal Marines

- Southern Diving Group RN

- Defence Estates South West

- HQ Western Division Ministry of Defence Police

- CID Devonport MOD Police

- DSG Devonport MOD Police

South Yard redevelopment

Several sections of the historic South Yard are no longer used by the Ministry of Defence, though it is still currently a closed site and subject to security restrictions.

The deep-water access it offers has made the site desirable for manufacturers of 'superyachts' and in 2012 Princess Yachts acquired the freehold to 20 acres at the southern end, with a view to building a construction facility.[29] The company asserts that this development will "continue the boat building tradition within the dockyard" and "add drama to the site with yachts being moved around the quayside, launched on No. 3 Slip, tested in No. 2 Slip and moored alongside the quay wall".[30] The site includes within it several listed buildings and scheduled ancient monuments, most notably the Grade I listed East Ropery,[31] together with several other 18th-century buildings and structures associated with rope-making in the Yard, the covered slip (No. 1 Slip) and the 'King's Hill Gazebo', built to commemorate a visit by King George III.[32]

In 2014 it was announced, as part of a 'City Deal' regeneration agreement, that the South Yard would be 'unlocked' with a view to it becoming a 'marine industries hub'.[33] As of 2016 the northern section of the South Yard (including the 18th-century dry docks, Nos. 2, 3 & 4)[34][35][36] was being redeveloped in phases,[37] with a marketing strategy focused on 'the development of marine industries and the high growth area of marine science and technology';[38] it has been renamed Oceansgate.

Areas to the south and east (with the exception of the area now occupied by Princess Yachts) are being retained by the MOD,[39] with No. 4 Slip having been recently refurbished for use with landing craft.[3]

Museum

.jpg)

The Devonport Naval Heritage Centre is a maritime museum in Devonport's Historic South Yard.[41] Run by volunteers, it is only accessible for pre-booked tours, or on Naval Base open days. Plymouth Naval Base Museum opened in 1969 following an appeal from the office of the Admiral-superintendent for items of memorabilia and was housed in the Dockyard Fire Station. Since then, the museum has expanded and now occupies, in addition, the 18th-century Pay Office[42] and Porter's Lodge. The Scrieve Board currently serves as a museum store.[3] Discussions were underway in 2014 around removing the museum from the Dockyard and displaying some of its collections within an expanded Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery.[43]

The nuclear-powered submarine HMS Courageous, used in the Falklands War, is preserved in North Yard as a museum ship, managed by the Heritage Centre.

Nickname

The Naval base at Devonport is still nicknamed "Guzz" (or, sometimes, "Guz") by sailors and marines. One suggestion is that this originates from the word guzzle (to eat or drink greedily), which is likely to refer to the eating of cream teas, a West Country delicacy and, therefore, one with strong connections to the area around Plymouth.[44] Another explanation advanced is that "GUZZ" was the radio call sign for the nearby Admiralty wireless station (which was GZX) at Devil's Point,[45] though this is disputed and has recently been disproved by reference to actual wireless telegraphy callsigns in existence over the past century.[46]

Another explanation is that the name came from the Hindi word for a yard (36 inches), "guz", (also spelled "guzz", at the time) which entered the Oxford English Dictionary,[47] and Royal Navy usage,[48] in the late 19th century, as sailors used to regularly abbreviate "The Dockyard" to simply "The Yard", leading to the slang use of the Hindi word for the unit of measurement of the same name.[49] The Plymouth Herald newspaper attempted[50] to summarise the differing theories, but no firm conclusion was reached. Charles Causley referred to Guz in one of his poems, "Song of the Dying Gunner A.A.1", published in 1951.[51]

A "tiddy oggy" is naval slang for a Cornish Pasty and which was once the nickname for a sailor born and bred in Devonport.[52] The traditional shout of "Oggy Oggy Oggy" was used to cheer on the Devonport team in the Navy's field gun competition.

Nuclear waste leaks

Devonport has been the site of a number of leaks of nuclear waste associated with the nuclear submarines based there.

- November 2002: "Ten litres of radioactive coolant leaked from HMS Vanguard."[53]

- October 2005: "Previous reported radioactive spills at the dockyard include one in October 2005, when it was confirmed 10 litres of water leaked out as the main reactor circuit of HMS Victorious was being cleaned to reduce radiation."[54]

- November 2008: "The Royal Navy has confirmed up to 280 litres of water, likely to have been contaminated with tritium, poured from a burst hose as it was being pumped from the submarine in the early hours of Friday."[54]

- March 2009: "On 25 March radioactive water escaped from HMS Turbulent while the reactor's discharge system was being flushed at the Devonport naval dockyard"[55]

References

- ↑ "HNMB Devonport". Royal Navy. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "HMNB Devonport". Archived from the original on 8 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Devonport in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). Historic England.

- ↑ Devonport Naval Base Handbook, 2010 Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hansard House of Commons (23 February 2015) Defence questions

- ↑ Wessom, William (24 September 2007). "The Devonport Royal dockyard". Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ↑ Fox, Celina (2007). "The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England" (PDF). Electronic British Library Journal. p. 26. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ MacDougall, Philip (September 2004). "Edmund Dummer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Listed building text". Historic England.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "BBC - Plymouth's proud naval history". Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 English Heritage: Thematic Survey of Naval Dockyards in England

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England.

- 1 2 Coad, Jonathan (2013). Support for the Fleet: architecture and engineering of the Royal Navy's bases 1700-1914. Swindon: English Heritage.

- 1 2 3 "Historic England". Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "HAR register - Sawmills". Historic England.

- ↑ "HAR register - Smithery". Historic England.

- ↑ English Heritage: Thematic History of Ordnance Yards and Magazine Depots Archived 22 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Plotting Plymouth's Past - Devonport’s Dock Lines" (PDF). www.plymouth.gov.uk. Old Plymouth Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ Liz Cook. "1914 Guide for Visitors to Devonport Dockyard". Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Weston Mill Lake, HM Naval Base Devonport: Construction of a jetty using concrete caissons". Institution of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "RM Tamar". MOD. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "MOD Heritage Report 2009-2011" (PDF). UK Government.

- ↑ A history of HMS Drake

- ↑ "Historical information on Subterranea Britannica".

- 1 2 Morris, Jonathan. "Devonport nuclear base has special measures extended". BBC News. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Boss of Plymouth's Princess Yachts vows not to cut any of 2,200 staff". Plymouth Herald. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Historic Impact Assessment" (PDF). Plymouth City Council. Princess Yachts. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Historic City Deal could unlock business boom and 10,000 jobs for Plymouth". Plymouth Herald. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Listed building description No2". Historic England. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Listed building description No3". Historic England.

- ↑ "Listed building description No4". Historic England.

- ↑ "Marketing brochure" (PDF). Plymouth City Council. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Marine Industries Demand Study Report" (PDF). Plymouth City Council. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Site". Oceansgate Plymouth. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Website Disabled". Plymouthnavalmuseum.com. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England.

- ↑ "Naval heritage centre set for city centre move as part of £21m history development". The Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Pompey, Chats and Guz: the Origins of Naval Town Nicknames | Online Information Bank | Research Collections | Royal Naval Museum at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard". Royalnavalmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Moseley, Brian (February 2011). "Plymouth, Royal Navy Establishments – Royal Naval Barracks (HMS Vivid / HMS Drake)". The Encyclopaedia of Plymouth History. Plymouth Data. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2015. (citing Brimacombe, Peter, "The History of HMS Drake", Rodney Brimacombe, Mor Marketing, Plymouth, July 1992.)

- ↑ See, for example: Dykes, Godfrey. "THE_PLYMOUTH_COMMAND". Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ↑ "A Minor case: OED contributions from a prison cell".

- ↑ Bedford, Sir Frederick (1875). Royal Navy "Sailor’s Pocket Book".

- ↑ "The Plymouth Command - Origin of the Nickname GUZZ".

- ↑ "Why are Plymouth and Devonport called Guzz". Plymouth Herald. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Neil Philip, Michael McCurdy. "War and the pity of war". Google.co.uk. p. 57. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Jolly, Rick (1989), Jackspeak: A guide to British Naval slang & usage, Conway (Bloomsbury Publishing Plc) ISBN 978-1-8448-6144-6 (p. 462)

- ↑ "Radioactive leak at Devonport". BBC News. 28 November 2002. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- 1 2 Enforcer, The (11 November 2008). "Radioactive leak at Devonport". This is Plymouth. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, Rob (18 May 2009). "Ministry of Defence admits to further radioactive leaks from submarines". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

External links

- HMNB Devonport web page

- Babcock International Group plc., the owner of the dockyard

- Devonport Naval Heritage Centre

- Oceansgate - marketing site for the South Yard development

Coordinates: 50°22′59″N 4°10′59″W / 50.383°N 4.183°W