Psalm 22

Psalm 22 is the 22nd Hebrew psalm in the Book of Psalms (Christian Greek Old Testament numbering 21).

Aijeleth Shahar

Aijeleth Shahar or Ayelet HaShachar (Hebrew: "hind of the dawn") is found in the title of the Psalm. It is probably the name of some song or tune to the measure of which the psalm was to be chanted.[1] Some, however, understand by the name some instrument of music, or an allegorical allusion to the subject of the psalms.

Heading

Where English translations have "Psalm," the underlying Hebrew word is מִזְמוֹר (mizmor), a song with instrumental accompaniment. This is part of the series of "Davidic Psalms" (mizmor le-david). Traditionally, their authorship was attributed to King David. In scholarly exegesis this write-up is no longer represented in the 19th century. The Hebrew particle le, means "of", "about", "for" or "in the manner of," so that it remains unclear whether the Davidic psalms originate with David, or simply take Davidic kingship as their topic, or take even in his own way the psalms terms.[2]

The heading further assigns the psalm as "for the conductor." This is apparently a reference to the use of Psalms in the (temple) liturgy. The exact meaning is unclear.[3]

The song is to be sung to the tune "Hind of Dawn", in a style apparently known to the original audience, according to the traditional interpretation. In the recent literature, however, it is argued that "Hind of Dawn" cultic role of the priest designated person acting as menatseach, as head of the ritual.

Historical-Critical Analysis

In terms of the exegetical analysis of this psalm, it is not widely regarded as being a unified whole. Psalm 22 is understood to have originally consisted of the contents of verses 1-22/23, with the later addition of 23/24-32.[4] Further analysis also recognizes verses 4-6 as part of the later addition, and finds a third editorial development layer in verses 28-32 in.[5] The exact distinction between the two main parts of the psalm is also controversial, as verse 23 is sometimes counted as a part of the original psalm, but sometimes as part of the later addition.

The emergence of the original psalm (vv 2-22 / 23) is thought to date from the pre-exilic period, that is, before the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 587. The second part was probably added only in the post-exilic period because of significant rescue of Israel. The last operation (V. 28-32) is, because of the universalist perspective the Hellenistic period, though to date from the late 4th century. [6]

Commentary

The reproachful, plaintive question "why" of suffering (v 2) in the 22nd Psalm touches the deepest sense of godforsakenness in the face of suffering and multiple persecution by enemies.[7] Because of the vagueness of the plea being made by the first part of the Psalm it has thus become a timeless testimony applicable to many typical situations of persecution. The complaint about the absence of God will multiply by praise (V. 4), confidences (V. 5-6, 10-11) and petitions (vv 20-22) interrupted.[8]

The second part of the Psalm is the gratitude of the petitioner in the light of his salvation (v.22) in the context of Israel (V. 26-27) and expands in worship YHWH the perspective of the peoples of the world that impressed God's action should show.[9]

In the New Testament Jesus cites Psalm 22 shortly before his death on the cross, to make himself the Psalm petitioner, and to own, according to Jewish tradition, the entire contents of the psalm.[10] Even in the biggest agony and abandonment God remains close at hand.

Christologically this part was considered offensive, inasmuch as Jesus Christ, who is God's Person of the Trinity in Christianity, can say that God had forsaken him. However, as in the Psalm abandonment by God is not the end. Rather, following in both cases is the sudden and abrupt rescue of the petitioner by God, in the New Testament Jesus' resurrection. The usual division of the Psalm into an action part (Ps 22.2 to 22 EU) and a praise or thanks part (Ps 22.23 to 32 EU) therefore is in Christianity (including Martin Luther) on the one hand with regard to the crucifixion and on the other hand pointed to the resurrection.[11]

Uses

Judaism

In the most general sense, Psalm 22 is about a person who is crying out to God to save him from the taunts and torments of his enemies, and (in the last ten verses) thanking God for rescuing him.

Jewish interpretations of Tehillim 22 identify the individual in the Psalm with a royal figure, usually King David or Queen Esther.[12] There is no evidence of the Psalm being used in a Jewish messianic context.

The Psalm is also interpreted as referring to the plight of the Jewish people and their distress and alienation in exile. [13] For instance, the phrase "But I am a worm" (Hebrew: ואנכי תולעת) refers to Israel, similarly to Isaiah 41 "Fear not, thou worm Jacob, and ye men of Israel; I help thee, saith the LORD, and thy Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel."[14]

- Is recited on the Fast of Esther.[15]

- Verse 4 is part of the opening paragraph of Uva Letzion.[16]

- Verse 26 is found in the repetition of the Amidah during Rosh Hashanah.[17]

- Verse 29 is a part of Az Yashir. It is recited following the passage from Exodus.[18] On Rosh Hashanah, it is found in the repetition of the Amidah.[19]

Christianity

The New Testament makes numerous allusions to Psalm 22, mainly during the crucifixion of Jesus.

- "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Psalm 22:1; Mark 15:34; Matthew 27:46)

- "They hurl insults, shaking their heads." (Psalm 22:7; Mark 15:29; Matthew 27:39)

- "They divide my clothes among them and cast lots for my garment." (Psalm 22:18; Mark 15:24; Matthew 27:35; Luke 23:34; John 19:24)

- "I will declare your name to my people; in the assembly I will praise you." (Psalm 22:22; Hebrews 2:12)

Christians also contend "They have pierced my hands and my feet" (Psalm 22:16), and "I can count all my bones" (Psalm 22:17) indicate the manner of Jesus's crucifixion, being nailed to the cross (John 20:25) and also that, per the Levitical code, no bones of the sacrifice (Numbers 9:11-13) may be broken. (Christians view Jesus as an atoning sacrifice)

Catholic Liturgy

In the Roman Rite, prior to the implementation of the Mass of Paul VI, this psalm was sung at the Stripping of the Altar on Maundy Thursday to signify the stripping of Christ's garments before crucifixion. The psalm was preceded and followed by the antiphon "Diviserunt sibi vestimenta mea: et super vestem meam miserunt sortem" (They divided my clothes among them and cast lots for my garment).[20] The chanting of this psalm was suppressed in the 1970 revisions to the Mass. It is still included in many parts of the Anglican Communion.

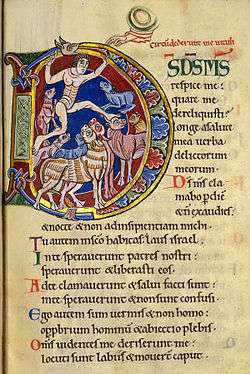

Since the Middle Ages, this psalm was traditionally performed during the celebration of the vigils dimanche,[21][22] according to the Rule of St. Benedict set to 530, as St. Benedict of Nursia simply attributed Psalms 21 (20) 109 (108) offices vigils, "all sitting with ordre.[23] "

In the Liturgy of the Hours now, Psalm 22 is sung or recited the Friday of the third week to the Office of the middle of the day.[24]

See also

- Christian messianic prophecies

- Crucifixion of Jesus

- David

- Eli, Eli (disambiguation)

- Eli Eli Lama Sabachthani? (disambiguation)

- Kermes ilicis or Kermes vermilio

- Sayings of Jesus on the cross

- They have pierced my hands and my feet

- Related Bible parts: Isaiah 1, Isaiah 53, Zechariah 12, Matthew 27, Mark 15, Luke 1, Luke 23, John 19, Hebrews 2, Revelation 1

References

- ↑ See for example Charles Augustus Briggs; Emilie Grace Briggs (1960) [1906]. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. International Critical Commentary. 1. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. p. 190.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Kraus: Psalmen 1–59, p.16–17

- ↑ John F. A. Sawyer: The Terminology of the Psalm Headings. In: Ders.: Sacred Texts and Sacred Meanings. Studies in Biblical Language and Literature. Sheffield, 2011.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Kraus: Psalmen 1–59; p.232.

- ↑ Frank-Lothar Hossfeld, Erich Zenger: Die Psalmen I. Psalm 1–50; p145.

- ↑ Frank-Lothar Hossfeld, Erich Zenger: Die Psalmen I. Psalm 1–50; p.145.

- ↑ Dörte Bester: Körperbilder in den Psalmen: Studien zu Psalm 22 und verwandten Texten. (= Band 24 von Forschungen zum Alten Testament), Mohr Siebeck, 2007,

- ↑ Dörte Bester: Körperbilder in den Psalmen: Studien zu Psalm 22 und verwandten Texten. (= Band 24 von Forschungen zum Alten Testament), Mohr Siebeck, 2007,

- ↑ Dörte Bester: Körperbilder in den Psalmen: Studien zu Psalm 22 und verwandten Texten. (= Band 24 von Forschungen zum Alten Testament), Mohr Siebeck, 2007.

- ↑ Eberhard Bons: Psalm 22 und die Passionsgeschichten der Evangelien. Neukirchener Verlag, 2007.

- ↑ Eberhard Bons: Psalm 22 und die Passionsgeschichten der Evangelien. Neukirchener Verlag, 2007.

- ↑ Psalm 22

- ↑ Writing and Reading the Scroll of Isaiah: Studies of an Interpretative Tradition, p.413

- ↑ Isaiah 41

- ↑ The Artscroll Tehillim p. 329

- ↑ The Complete Artscroll Siddur p. 155

- ↑ The Complete Artscroll Machzor for Rosh Hashanah p. 353

- ↑ The Complete Artscroll Siddur p. 80

- ↑ The Complete Artscroll Machzor for Rosh Hashanah p. 321

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Stripping of an Altar". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Stripping of an Altar". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Psautier latin-français du bréviaire monastique, p. 62, 1938/2003

- ↑ [archive ].

- ↑ traduction de Prosper Guéranger, Règle de saint Benoît, (Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes, réimpression 2007) p. 39.

- ↑ Le cycle des prières liturgiques principales se déroule sur quatre semaines.

External links

- Psalm 22 in Parallel English (JPS translation) and Hebrew

- Text of Psalm 22 in English, New International Version