Desertification

Desertification is a type of land degradation in which relatively dry area of land becomes increasingly arid, typically losing its bodies of water as well as vegetation and wildlife.[2] It is caused by a variety of factors, such as through climate change and through the overexploitation of soil through human activity.[3] When deserts appear automatically over the natural course of a planet's life cycle, then it can be called a natural phenomenon; however, when deserts emerge due to the rampant and unchecked depletion of nutrients in soil that are essential for it to remain arable, then a virtual "soil death" can be spoken of,[4] which traces its cause back to human overexploitation. Desertification is a significant global ecological and environmental problem.[5]

Definitions

Considerable controversy exists over the proper definition of the term "desertification" for which Helmut Geist (2005) has identified more than 100 formal definitions. The most widely accepted[2] of these is that of the Princeton University Dictionary which defines it as "the process of fertile land transforming into desert typically as a result of deforestation, drought or improper/inappropriate agriculture".[6]

Desertification has been neatly defined in the text of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) as "land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid regions resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities."[7]

Another major contribution to the controversy comes from the sub-grouping of types of desertification. Spanning from the very vague yet shortsighted view as the "man-made-desert" to the more broad yet less focused type as the "Non-pattern-Desert"[8]

The earliest known discussion of the topic arose soon after the French colonization of West Africa, when the Comité d'Etudes commissioned a study on desséchement progressif to explore the prehistoric expansion of the Sahara Desert.[9]

History

The world's most noted deserts have been formed by natural processes interacting over long intervals of time. During most of these times, deserts have grown and shrunk independent of human activities. Paleodeserts are large sand seas now inactive because they are stabilized by vegetation, some extending beyond the present margins of core deserts, such as the Sahara, the largest hot desert.[10]

Desertification has played a significant role in human history, contributing to the collapse of several large empires, such as Carthage, Greece, and the Roman Empire, as well as causing displacement of local populations.[5][11][12][13][14] Historical evidence shows that the serious and extensive land deterioration occurring several centuries ago in arid regions had three epicenters: the Mediterranean, the Mesopotamian Valley, and the Loess Plateau of China, where population was dense.[11][15]

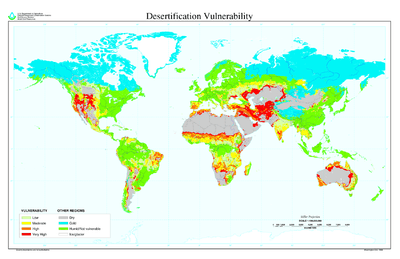

Areas affected

.jpg)

Drylands occupy approximately 40–41% of Earth’s land area[17][18] and are home to more than 2 billion people.[18] It has been estimated that some 10–20% of drylands are already degraded, the total area affected by desertification being between 6 and 12 million square kilometres, that about 1–6% of the inhabitants of drylands live in desertified areas, and that a billion people are under threat from further desertification.[19][20]

As of 1998, the then-current degree of southward expansion of the Sahara was not well known, due to a lack of recent, measurable expansion of the desert into the Sahel at the time.[21]

Causes of desertification in Sahel:

The impact of global warming and human activities are presented in the Sahel. In this area, the level of desertification is very high compared to other areas in the world.

All areas situated in the eastern part of Africa (i.e. in the Sahel region) are characterized by a dry climate, hot temperatures, and low rainfall (300–750 mm rainfall per year). So, droughts are the rule in the Sahel region.[22]

Development of the desertification process in Sahel:

Some studies have shown that Africa has lost approximately 650 000 km² of its productive agricultural land over the past 50 years. The propagation of desertification in this area is considerable.[23]

Some statistics have shown that since 1900, the Sahara has expanded by 250 km, covering an additional area of 6000 square kilometers.[23]

Impacts of desertification in Sahel:

The survey, done by the research institute for development, had demonstrated that this means dryness is spreading fast in the Sahelian countries. Desertification in the Sahel can affect more than one billion of its inhabitants. 70% of the arid area has deteriorated and water resources have disappeared, leading to soil degradation. The loss of topsoil means that plants cannot take root firmly and can be uprooted by torrential water or strong winds.[23][24]

The United Nations Convention (UNC) says that about six million Sahelian citizens would have to give up the desertified zones of sub-Saharan Africa for North Africa and Europe between 1997 and 2020.[23][24]

China and the Gobi

Another major area that is being impacted by desertification is the Gobi Desert. Currently, the Gobi desert is the fastest moving desert on Earth; according to some researchers, the Gobi Desert swallows up over 1,300 miles of land annually. This has destroyed many villages in its path. Currently, photos show that the Gobi Desert has expanded to the point the entire nation of Croatia could fit inside its area.[25] This is causing a major problem for the people of China. They will soon have to deal with the desert as it creeps closer. Although the Gobi Desert itself is still a distance away from Beijing, reports from field studies state there are large sand dunes forming only 70 km(43.5m) outside of the city.[26]

Vegetation patterning

As the desertification takes place, the landscape may progress through different stages and continuously transform in appearance. On gradually sloped terrain, desertification can create increasingly larger empty spaces over a large strip of land, a phenomenon known as "Brousse tigrée". A mathematical model of this phenomenon proposed by C. Klausmeier attributes this patterning to dynamics in plant-water interaction.[27] One outcome of this observation suggests an optimal planting strategy for agriculture in arid environments.[28]

Causes

The immediate cause is the loss of most vegetation. This is driven by a number of factors, alone or in combination, such as drought, climatic shifts, tillage for agriculture, overgrazing and deforestation for fuel or construction materials. Vegetation plays a major role in determining the biological composition of the soil. Studies have shown that, in many environments, the rate of erosion and runoff decreases exponentially with increased vegetation cover.[32] Unprotected, dry soil surfaces blow away with the wind or are washed away by flash floods, leaving infertile lower soil layers that bake in the sun and become an unproductive hardpan. Controversially, Allan Savory has claimed that the controlled movement of herds of livestock, mimicking herds of grazing wildlife, can reverse desertification.[33][34][35][36][37]

It causes because of human causes

Poverty

At least 90% of the inhabitants of drylands live in developing nations, where they also suffer from poor economic and social conditions.[19] This situation is exacerbated by land degradation because of the reduction in productivity, the precariousness of living conditions and the difficulty of access to resources and opportunities.[38]

A downward spiral is created in many underdeveloped countries by overgrazing, land exhaustion and overdrafting of groundwater in many of the marginally productive world regions due to overpopulation pressures to exploit marginal drylands for farming. Decision-makers are understandably averse to invest in arid zones with low potential. This absence of investment contributes to the marginalisation of these zones. When unfavourable agro-climatic conditions are combined with an absence of infrastructure and access to markets, as well as poorly adapted production techniques and an underfed and undereducated population, most such zones are excluded from development.[39]

Desertification often causes rural lands to become unable to support the same sized populations that previously lived there. This results in mass migrations out of rural areas and into urban areas, particularly in Africa. These migrations into the cities often cause large numbers of unemployed people, who end up living in slums.[40][41]

Countermeasures and prevention

Techniques and countermeasures exist for mitigating or reversing the effects of desertification, and some possess varying levels of difficulty. For some, there are numerous barriers to their implementation. Yet for others, the solution simply requires the exercise of human reason.

One less difficult solution that has been proposed,[43] however controversial it may be, is to bring about a cap on the population growth, and in fact to turn this into a population decay, so that each year there will gradually exist fewer and fewer humans who require the land to be depleted even further in order to grow their food.

One proposed barrier is that the costs of adopting sustainable agricultural practices sometimes exceed the benefits for individual farmers, even while they are socially and environmentally beneficial.[44] Another issue is a lack of political will, and lack of funding to support land reclamation and anti-desertification programs.[45]

Desertification is recognized as a major threat to biodiversity. Some countries have developed Biodiversity Action Plans to counter its effects, particularly in relation to the protection of endangered flora and fauna.[46][47]

Reforestation gets at one of the root causes of desertification and is not just a treatment of the symptoms. Environmental organizations[48] work in places where deforestation and desertification are contributing to extreme poverty. There they focus primarily on educating the local population about the dangers of deforestation and sometimes employ them to grow seedlings, which they transfer to severely deforested areas during the rainy season.[49] The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations launched the FAO Drylands Restoration Initiative in 2012 to draw together knowledge and experience on dryland restoration.[50] In 2015, FAO published global guidelines for the restoration of degraded forests and landscapes in drylands, in collaboration with the Turkish Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs and the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency.[51]

Currently, one of the major methods that has been finding success in this battle with desertification. This is known as China's "Great Green Wall." This wall is a much larger scaled version of what American farmers did in the 1930s to stop the great Midwest dust bowl. This plan was proposed in the late 70's, and has become a major ecological engineering project that is not predicted to end until the year 2055. According to Chinese reports, there have been nearly 66,000,000,000 tress planted in China's great green wall.[52] Due to the success that China has been finding in stopping the spread of desertification. Through their success with their wall, plans are currently be made in Africa to start a "wall" along the borders of the Sahara desert as well.

Techniques focus on two aspects: provisioning of water, and fixation and hyper-fertilizing soil.

Fixating the soil is often done through the use of shelter belts, woodlots and windbreaks. Windbreaks are made from trees and bushes and are used to reduce soil erosion and evapotranspiration. They were widely encouraged by development agencies from the middle of the 1980s in the Sahel area of Africa.

Some soils (for example, clay), due to lack of water can become consolidated rather than porous (as in the case of sandy soils). Some techniques as zaï or tillage are then used to still allow the planting of crops.[53]

Another technique that is useful is contour trenching. This involves the digging of 150m long, 1m deep trenches in the soil. The trenches are made parallel to the height lines of the landscape, preventing the water from flowing within the trenches and causing erosion. Stone walls are placed around the trenches to prevent the trenches from closing up again. The method was invented by Peter Westerveld.[54]

Enriching of the soil and restoration of its fertility is often done by plants. Of these, leguminous plants which extract nitrogen from the air and fix it in the soil, and food crops/trees as grains, barley, beans and dates are the most important. Sand fences can also be used to control drifting of soil and sand erosion.[55]

Some research centra (such as Bel-Air Research Center IRD/ISRA/UCAD) are also experimenting with the inoculation of tree species with mycorrhiza in arid zones. The mycorrhiza are basically fungi attaching themselves to the roots of the plants. They hereby create a symbiotic relation with the trees, increasing the surface area of the tree's roots greatly (allowing the tree to gather much more nutrients from the soil).[56]

As there are many different types of deserts, there are also different types of desert reclamation methodologies. An example for this is the salt-flats in the Rub' al Khali desert in Saudi-Arabia. These salt-flats are one of the most promising desert areas for seawater agriculture and could be revitalized without the use of freshwater or much energy.[57]

Farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) is another technique that has produced successful results for desert reclamation. Since 1980, this method to reforest degraded landscape has been applied with some success in Niger. This simple and low-cost method has enabled farmers to regenerate some 30,000 square kilometers in Niger. The process involves enabling native sprouting tree growth through selective pruning of shrub shoots. The residue from pruned trees can be used to provide mulching for fields thus increasing soil water retention and reducing evaporation. Additionally, properly spaced and pruned trees can increase crop yields. The Humbo Assisted Regeneration Project which uses FMNR techniques in Ethiopia has received money from The World Bank’s BioCarbon Fund, which supports projects that sequester or conserve carbon in forests or agricultural ecosystems.[58]

Managed grazing

Restoring grasslands store CO2 from the air into plant material. Grazing livestock, usually not left to wander, would eat the grass and would minimize any grass growth while grass left alone would eventually grow to cover its own growing buds, preventing them from photosynthesizing and killing the plant.[60] A method proposed to restore grasslands uses fences with many small paddocks and moving herds from one paddock to another after a day or two in order to mimic natural grazers and allowing the grass to grow optimally.[60][61][62] It is estimated that increasing the carbon content of the soils in the world’s 3.5 billion hectares of agricultural grassland would offset nearly 12 years of CO2 emissions.[60] Allan Savory, as part of holistic management, claims that while large herds are often blamed for desertification, prehistoric lands used to support large or larger herds and areas where herds were removed in the United States are still desertifying.[59]

See also

- Aridification

- Arid Forest Research Institute

- Deforestation

- Green water credits

- Oasification

- Poopó Lake a saline lake that no longer exists

- Soil retrogression and degradation

- Terraforming

- Water crisis

- Deforestation and climate change

Mitigation:

- Arid Lands Information Network—Kenya

- Biochar Fertilisation using carbon

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

- Economics of Land Degradation Initiative

- Desert greening

- Ecological engineering

- Green Wall of China

- Holistic management

- Land value tax

References

- ↑ Mayell, Hillary (April 26, 2001). "Shrinking African Lake Offers Lesson on Finite Resources". National Geographic News. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- 1 2 Geist (2005), p. 2

- ↑ "Sustainable development of drylands and combating desertification". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Desert Will Win". FIGU-Landesgruppe Canada. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- 1 2 Geist (2005), p. 4

- ↑ "define:desertification – Google Search". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ "Part I". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ Helmut J. Geist, and Eric F. Lambin. "Dynamic Causal Patterns of Desertifcation." BioScience 54.9 (2004): 817 . Web.

- ↑ Mortimore, Michael (1989). Adapting to drought: farmers, famines, and desertification in west Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-32312-3.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey, "Desertification", 1997

- 1 2 LOWDERMILK, W C. "CONQUEST OF THE LAND THROUGH SEVEN THOUSAND YEARS" (PDF). Soil Conservation Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ Whitford, Walter G. (2002). Ecology of desert systems. Academic Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-12-747261-4.

- ↑ Bogumil Terminski (2011), Towards Recognition and Protection of Forced Environmental Migrants in the Public International Law: Refugee or IDPs Umbrella, Policy Studies Organization (PSO), Washington.

- ↑ Geist, Helmut. "The causes and progression of desertification". Antony Rowe Ltd. Ashgate publishing limited. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Dregne, H.E. "Desertification of Arid Lands". Columbia University. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Sun, Moon and Telescopes above the Desert". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Bauer (2007), p. 78

- 1 2 Johnson et al (2006), p. 1

- 1 2 "UNCCD – Error 404 – Page Not Found" (PDF). Retrieved 21 June 2016. horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 7 (help) - ↑ World Bank (2009). Gender in agriculture sourcebook. World Bank Publications. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-8213-7587-7.

- ↑

- ↑ Riebeek, Holli (2007-01-03). "Defining Desertification : Feature Articles". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "La progression du désert du Sahara augmente chaque année ?". Savezvousque.fr. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- 1 2 "United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: Issues and Challenges". E-International Relations. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/10/24/world/asia/living-in-chinas-expanding-deserts.html?_r=0

- ↑ http://www.geo.utexas.edu/courses/371c/project/2009/Welker_Desertification.pdf

- ↑ Klausmeier, Christopher (1999). "Regular and irregular patterns in semiarid vegetation". Science. 284 (5421): 1826–1828. doi:10.1126/science.284.5421.1826.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Grid of straw squares turns Chinese sand to soil – Environment – DW.COM – 23.06.2011". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ Laduke, Winona (1999). All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (PDF). Cambridge, MA: South End Press. p. 146. ISBN 0896085996. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Duval, Clay. "Bison Conservation: Saving an Ecologically and Culturally Keystone Species" (PDF). Duke University. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Holistic Land Management: Key to Global Stability" by Terry Waghorn. Forbes. 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Geeson, Nichola et al. (2002). Mediterranean desertification: a mosaic of processes and responses. John Wiley & Sons. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-470-84448-9.

- ↑ Savory, Allan. "Allan Savory: How to green the world's deserts and reverse climate change".

- ↑ Savory, Allan. "Holistic resource management: a conceptual framework for ecologically sound economic modelling" (PDF). Ecological Economics. Elsevier Science Publishers. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Butterfield, Jody (2006). Holistic Management Handbook: Healthy Land, Healthy Profits, Second Edition. Island Press. ISBN 1559638850.

- ↑ Savory, Allan. "Response to request for information on the "science" and "methodology" underpinning Holistic Management and holistic planned grazing" (PDF). Savory Institute. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Drury, Steve. "Large-animal extinction in Australia linked to human hunters". Earth-Pages. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ Dobie, Ph. 2001. “Poverty and the drylands”, in Global Drylands Imperative, Challenge paper, Undp, Nairobi (Kenya) 16 p.

- ↑ Cornet A., 2002. Desertification and its relationship to the environment and development: a problem that affects us all. In: Ministère des Affaires étrangères/adpf, Johannesburg. World Summit on Sustainable Development. 2002. What is at stake? The contribution of scientists to the debate: 91–125..

- ↑ Pasternak, Dov & Schlissel, Arnold (2001). Combating desertification with plants. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-306-46632-8.

- ↑ Briassoulis, Helen (2005). Policy integration for complex environmental problems: the example of Mediterranean desertification. Ashgate Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-7546-4243-5.

- ↑ Pasternak, D.; Schlissel, Arnold. Combating Desertification with Plants. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 38. ISBN 9781461513278.

- ↑ "The Future Of Mankind – A Billy Meier Wiki – Overpopulation Crusade". www.futureofmankind.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ↑ Drost, Daniel; Long, Gilbert; Wilson, David; Miller, Bruce; Campbell, William (1 December 1996). "Barriers to Adopting Sustainable Agricultural Practices". Journal of Extension.

- ↑ Briassoulis, Helen (2005). Policy integration for complex environmental problems: the example of Mediterranean desertification. Ashgate Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-7546-4243-5.

- ↑ Techniques for Desert Reclamation by Andrew S. Goudie

- ↑ Desert reclamation projects

- ↑ For example, Eden Reforestation Projects website, on Vimeo, on Eden Reforestation Projects on YouTube.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/deserts/desertification/".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/deserts/desertification/". - ↑ "Drylands Restoration Initiative". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ Global guidelines for the restoration of degraded forests and landscapes in drylands (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. June 2015. ISBN 978-92-5-108912-5. Retrieved June 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/04/china-great-green-wall-gobi-tengger-desertification/

- ↑ "Our Good Earth – National Geographic Magazine". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ "Home – Justdiggit". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ List of plants to halt desertification; some of which may be soil-fixating

- ↑ "Département Biologie Végétale – Laboratoire Commun de Microbiologie IRD-ISRA-UCAD". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ Rethinking landscapes, Nicol-André Berdellé July 2011 H2O magazine

- ↑ "Sprouting Trees From the Underground Forest — A Simple Way to Fight Desertification and Climate Change – Water Matters – State of the Planet". Blogs.ei.columbia.edu. 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- 1 2 "How cows could repair the world". nationalgeographic.com. March 6, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "How fences could save the planet". newstatesman.com. January 13, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Restoring soil carbon can reverse global warming, desertification and biodiversity". mongabay.com. February 21, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Abend, Lisa (January 25, 2010). "How eating grass-fed beef could help fight climate change". time.com. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

Bibliography

- Arnalds, Ólafur; Archer, Steve (2000). Rangeland Desertification. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-6071-1.

- Barbault R., Cornet A., Jouzel J., Mégie G., Sachs I., Weber J. (2002). Johannesburg. World Summit on Sustainable Development. 2002. What is at stake? The contribution of scientists to the debate. Ministère des Affaires étrangères/adpf.

- Bauer, Steffan (2007). "Desertification". In Thai, Khi V. et al. Handbook of globalization and the environment. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-57444-553-4.

- Batterbury, S.P.J. & A.Warren (2001) Desertification. in N. Smelser & P. Baltes (eds.) International Encyclopædia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier Press. pp. 3526–3529

- Geist, Helmut (2005). The causes and progression of desertification. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4323-4.

- Hartman, Ingrid (2008). "Desertification". In Philander, S. George. Encyclopedia of global warming and climate change, Volume 1. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-5878-3.

- Hinman, C. Wiley & Hinman, Jack W. (1992). The plight and promise of arid land agriculture. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06612-9.

- Holtz, Uwe (2007). Implementing the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification from a parliamentary point of view – Critical assessment and challenges ahead. Online at

- Holtz, Uwe (2013). Role of parliamentarians in the implementation process of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. A guide to Parliamentary Action, ed. Secretariat of the UNCCD, Bonn ISBN 978-92-95043-69-5. Online at

- Johnson, Pierre Marc et al., eds. (2006). Governing global desertification: linking environmental degradation, poverty and participation. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4359-3.

- Lucke, Bernhard (2007): Demise of the Decapolis. Past and Present Desertification in the Context of Soil Development, Land Use, and Climate. Online at

- Mensah, Joseph (2006). "Desertification". In Leonard, Thomas M. Encyclopedia of the developing world, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-97662-6.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Desertification Synthesis Report

- Moseley, W.G. and E. Jerme 2010. “Desertification.” In: Warf, B. (ed). Encyclopedia of Geography. Sage Publications. Volume 2, pp. 715–719.

- Oliver, John E., ed. (2005). "Desertification". Encyclopedia of world climatology. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- Parrillo, Vincent N., ed. (2008). "Desertification". Encyclopedia of social problems, Volume 2. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-4165-5.

- Reynolds, James F., and D. Mark Stafford Smith (ed.) (2002) Global Desertification – Do Humans Cause Deserts? Dahlem Workshop Report 88, Berlin: Dahlem University Press

- Stelt, Sjors van der (2012) Rise and Fall of Periodic Patterns for a Generalized Klausmeier-Gray-Scott Model, PhD Thesis University of Amsterdam

- UNCCD (1994) United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

- The End of Eden a 90-minute documentary by South African filmmaker Rick Lomba in 1984 on African desertification

- Attribution

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/deserts/desertification/".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/deserts/desertification/".

External links

- Beyerlin, Ulrich. Desertification, Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

- Bell, Trudy; Phillips, Tony (December 6, 2002). "City-swallowing Sand Dunes". NASA. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- Desert Research Institute in Nevada, United States

- Environmental Issues – Desertification in Africa, The Environmental Blog

- Eden Foundation article on desertification

- FAO Information Portal – Properties and Management of Drylands

- UNEP (2006): Global Deserts Outlook

- UNEP Programme on Success Stories in Land Degradation/ Desertification Control

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification – Secretariat

- Procedural history and related documents on the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Dersertification, Particularly in Africa in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- A guide for desert and dryland restoration by David A. Bainbridge

- French Scientific Committee on Desertification (CSFD)

- Olive Trees May Be The Answer To Desertification

- The End of Eden on Youtube

- News

- Fighting Desertification Through Conservation Report on a project to stop the advance of the Sahara in Algeria – IPS, 27 February 2007