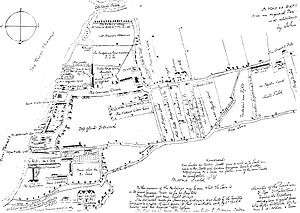

Deptford Dockyard

- Officers' houses & offices

- The double dry dock

- Quadrangular Great Storehouse

- A pair of shipbuilding slips

- Wet dock (or Basin)

- Shipbuilding slip

- Mast houses and mast pond

- Boat house.

Deptford Dockyard was an important naval dockyard and base at Deptford on the River Thames, in what is now the London Borough of Lewisham, operated by the Royal Navy from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. It built and maintained warships for 350 years, and many significant events and ships have been associated with it.

Founded by Henry VIII in 1513, the dockyard was the most significant royal dockyard of the Tudor period and remained one of the principal naval yards for three hundred years. Important new technological and organisational developments were trialled here, and Deptford came to be associated with the great mariners of the time, including Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh. The yard expanded rapidly throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, encompassing a large area and serving for a time as the headquarters of naval administration, and became the Victualling Board's main depot. Tsar Peter the Great visited the yard officially incognito in 1698 to learn shipbuilding techniques. Reaching its zenith in the eighteenth century, it built and refitted exploration ships used by Cook, Vancouver and Bligh, and warships which fought under Nelson.

The dockyard declined in importance after the Napoleonic Wars. Its location upriver on the Thames made access difficult, and the shallow narrow river hampered navigation of the large new warships. The dockyard was largely inactive after 1830, and though shipbuilding briefly returned in the 1840s the navy closed the yard in 1869. The victualling yard that had been established in the 1740s continued in use until the 1960s, while the land used by the dockyard was sold, the area now being known as Convoys Wharf.

History

Foundation

The Deptford area had been used to build royal ships since the early fifteenth century, during the reign of Henry V. Moves were made to improve the administration and operation of the Royal Navy during the Tudor period, and Henry VII founded the first royal dockyard at Portsmouth in 1496.[1] Henry's son, Henry VIII furthered his father's expansion plans, but preferred locations along the Thames to south coast ports, and established Woolwich Dockyard, followed by a dockyard at Deptford in 1513.[1][2]

The Tudor dockyard

The dockyard initially consisted of little more than a dry dock and a storehouse, with a pond being converted into a basin in 1517 to provide mooring for several of the King's ships.[1] More storehouses were built between 1513 and 1514 at Deptford and further down the Thames at Erith, in order to service the navy's needs in the War of the League of Cambrai.[3] The basin converted from the pond in 1517 was divided into three parts, covering a total of eight acres, and deep enough to take a 1000-ton ship.[4] The physical expansion of Deptford at this time was reflected in the increasing development and sophistication of naval administration, and with the creation of the antecedent of the Navy Board in the mid-sixteenth century, a new house was built at Deptford for the "officers' clerks of the Admiralty".[5]

The dockyard grew to be the most important of the royal dockyards, employing increasing numbers of workers, and expanding to incorporate new storehouses.[6] Its importance meant that it was visited on occasion by the monarch to inspect new ships building there. This was reflected in the expenditure of £88 by the Treasurer of the Navy in 1550 in order to pay for Deptford High Street to be paved, as the road was "previously so noisome and full of filth that the King's Majesty might not pass to and fro to see the building of his Highness's ships."[6]

The dock was rebuilt and wharves expanded to cover 500–600 feet of the river front by the end of the sixteenth century. It had by then become known as the "King's Yard".[1] Deptford became increasingly sophisticated in its operations, with £150 paid in 1578 to build gates for the dry dock, removing the necessity of constructing a temporary earth dockhead and then digging it away to free the ship once work had been completed.[7][a]

The significance of Deptford to English maritime strength was highlighted when Elizabeth I knighted Francis Drake at the dockyard in 1581 after his circumnavigation of the globe aboard the Golden Hind.[8] She ordered that the Golden Hind be moored in Deptford Creek for public exhibition, where the ship remained until the 1660s before rotting away and being broken up.[8][9] The dockyard is one of the locations associated with the story of Sir Walter Raleigh laying his cloak before Elizabeth's feet.[10] Deptford's significant role during this and later periods resulted in it being termed the "Cradle of the Navy."[9]

Expansion

.jpg)

The growth of other shipyards, particularly Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway, eventually threatened Deptford's supremacy, and by the early seventeenth century the possibility of closing and selling Deptford yard was being discussed. Though Deptford and Woolwich possessed the only working docks, the Thames was too narrow, shallow and heavily used and the London dockyards too far from the sea to make it an attractive anchorage for the growing navy.[11] Attention shifted to the Medway and defences and facilities were constructed at Chatham and Sheerness.[11]

Despite this, Deptford Dockyard continued to flourish and expand, being closely associated with the Pett dynasty, which produced several master shipwrights during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.[12] A commission in the navy in the 1620s decided to concentrate construction at Deptford. The commission ordered the construction of six great ships, three middling ships and one small ship, all from Andrew Borrell at Deptford, at a delivery rate of two a year for five years.[13] By the seventeenth century the yard covered a large area and included large numbers of storehouses, slipways, smiths, and other maintenance facilities and workshops.[1][14] The Great Dock was lengthened and enlarged in 1610, several slipways were remodelled and in 1620 a second dry dock was built, with a third being authorised in 1623.[1][15]

There was further investment in the Commonwealth period, with money spent on providing a mast dock and three new wharves.[16] The yard was visited by Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia, in 1698. He stayed in nearby Sayes Court, which had been temporarily let furnished by John Evelyn to Admiral John Benbow. During the Tsar's stay, Evelyn's servant wrote to him to report "There is a house full of people and right nasty. The Tsar lies next your library, and dines in the parlour next your study. He dines at ten o'clock and at six at night, is very seldom at home a whole day, very often in the King's Yard or by water, dressed in several dresses."[17] Peter studied shipbuilding techniques and practices at the dockyard.[18][b]

With the increasing specialisation among the royal dockyards, Deptford concentrated on building smaller warships and was the headquarters of the naval transport service.[19] Throughout the various wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the navy sought to relieve pressure on the main fleet bases by concentrating shipbuilding and fitting out at riverine docks like Chatham, Woolwich and Deptford, leaving the front-line dockyards at Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Nore for maintenance and repair.[20]

By the 1790s Deptford had five slipways for building warships, and by 1807 was also served by one sheer hulk based at the yard.[21] Deptford was associated with a large number of famous ships and people. Several of the ships used by James Cook on his voyages of exploration were refitted at the dockyard, including HMS Endeavour, HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery, as were ships used by George Vancouver on his expedition between 1791 and 1795, HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham.[22] HMS Bounty was refitted at the yard in 1787, as was HMS Providence, the vessel used by William Bligh on his second breadfruit expedition.[22][23] Warships built at the yard include HMS Neptune and HMS Colossus, which fought under Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, and HMS Swiftsure, which was captured in 1801 and fought for the French at the battle.[24]

Decline

The end of the Napoleonic Wars and the long period of relative peace that followed caused a decline in both the number of new ships demanded by the navy and the number that needed to be repaired and maintained. Deptford's location and the shallow riverine waters exacerbated the problem as work and contracts were moved to other royal dockyards.[1] The yard had its location close to the main navy offices in London in its favour, but the silting of the Thames and the trend towards larger warships made continued naval construction there an unappealing prospect. Engineer John Rennie commented of the yard that

Ships-of-the-line which are built there cannot as I am informed with propriety be docked and coppered. Jury masts are put into them and they are taken to Woolwich, where they are docked, coppered and rigged, and I have been told of an instance where many weeks elapsed before a fair wind and tide capable of floating a large ship down to Woolwich occurred.[25]

From 1821 only maintenance work was carried out at Deptford, and from 1830 the workload was reduced further as only shipbreaking was carried out there.[1] The yard was largely shut down between 1830 and 1844, though the navy was reported to have kept a keel laid down in building slip No. 1, in apparent fulfilment of a lease from John Evelyn, who had made it one of the terms that a ship was always to be under construction at the yard.[26] The navy had to hastily lay a keel down in 1843 when it was discovered that the term was not being adhered to.[26] Small-scale warship construction resumed in 1844, but the yard was deemed surplus to requirements and was closed in 1869.[18] The screw corvette HMS Druid, launched on 13 March 1869, was the final ship built there.[26]

Legacy

The land occupied by the Dockyard was sold after its closure, the area becoming known as Convoys Wharf.[26] T. P. Austin paid £70,000 for the land, which was then bought by the City of London Corporation for £91,500. Slaughterhouses were then constructed on the site.[26] A later periodical described how "Deptford Dockyard, dismantled and degraded from its olden service to the Navy, has just been converted into a foreign cattle market and a shambles."[26] The area's use as a Cattle Market continued until 1913; thereafter it was used as an army depot and then as warehouse space.[27] In 1980 the site was acquired by News International for the importing and storing of paper products; 28 years later they vacated the site, which now awaits redevelopment as a residential complex.

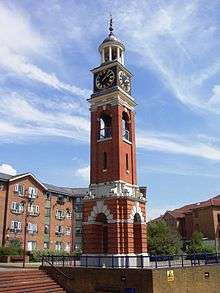

Many of the Royal Dockyard's buildings, facilities and features have been lost or destroyed since its closure, and its waterways infilled. Henry VIII's Great Storehouse of 1513 was demolished in 1954 (its bricks were used for repairs to Hampton Court Palace); and demolition of the adjacent eighteenth-century Storehouse buildings followed likewise in 1984.[d] A few buildings have survived, however, most notably the Master Shipwright's House of 1708 (built by Joseph Allin), the nearby Office Building of 1720 and (from a late period of the dockyard's existence) the prominent Olympia Warehouse of 1846. (This building, of distinctive iron construction, was originally a double shed, built over dual slipways alongside the main Basin to enable shipbuilding to take place under cover). Moreover, remains of many of the yard's core features, including the slipways, dry docks, basins, mast ponds and building foundations, still exist below ground level and have been studied in archaeological digs.[1] The subterranean remains of the Tudor Great Storehouse are now a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[28]

The Lenox Project

In 2013 the Lenox Project put forward a formal proposal to build a full-size sailing replica of HMS Lenox, a 70-gun ship of the line originally built at Deptford Dockyard in 1678. The ship would actually be constructed on the dockyard site, and would form the centrepiece of a purpose-built museum which would remain as a permanent part of the development of Convoys Wharf.[29]

By late 2015 the project had gathered momentum, with more detailed plans fitting the building of the Lenox into the overall development of this part of Deptford.[30] The 2015 Feasibility Study identified the Safeguarded Wharf at the Western end of the Convoys Wharf site as the most suitable place for the dry-dock where the ship herself would be built; the existing but disused canal entrance could then be modified to provide an entrance for the dock as well as a home berth for the finished ship. [31]

It is hoped that the Lenox will provide a focus for the regeneration of the area as the comparable replica ship Hermione did for Rochefort in France.

The Victualling Yard

Dockyard facilities were also used to resupply and victual the navy's warships; Deptford's Victualling Yard was founded upstream of the main dockyard: the Victualling Board leased the Red House estate in 1743 and established its main depot at Deptford, embarking on the construction of stores and mills.[12][32][33][c] In time, the two yards became physically merged as the dockyard expanded in the victualling yard, both being enclosed by a wall.[1] Deptford's proximity to the food markets of London made it especially convenient for victualling, and it served the requirements not only of its own neighbouring Dockyard, but those of Woolwich, Sheerness and Chatham as well. In 1858 it was renamed the Royal Victoria Victualling Yard, following similar re-brandings in Plymouth, Portsmouth and Ireland.

The Victualling Yard continued in operation for almost a century after the closure of the dockyard, dedicated to the manufacture and storage of food, drink, clothing and furniture for the navy, until its closure in 1961.[1][18]

A number of its buildings and other features can still be seen (in and around the Pepys Estate) all dating from the 1770-80s.[27] These include the gateway on Grove Street, the 'Colonnade' behind it (a series of houses fronted by a colonnaded passageway), the terrace of houses on Longshore, and the two former Rum Warehouses on the riverbank. The surrounding housing estate was built after the closure if the yard in the early 1960s, and the surviving naval buildings were converted at the same time to provide housing and community facilities.

Notes

a. ^ Dry dock gates existed at Chatham and Woolwich by the early part of the seventeenth century. Nicholas Rodger considers the introduction of dock gates as marking "...the invention of the true dry dock [which was] a very important development. It was to become one of the key technical achievements underpinning English sea power."[11] The first foreign true dry dock, described as 'a l'anglaise', was ordered at by the French at Rochefort in 1666, nearly a century after the English.[11]

b. ^ The unhappy Evelyn was able to convince the Treasury to pay him £350 to cover the necessary repair work to his house after the Russians' stay, after a survey of the damage was made by Sir Christopher Wren, the Surveyor of the King's Works.[17]

c. ^ By the 1790s the Victualling Board had its headquarters at Somerset House, together with the Navy and Transport Boards.[34]

d. ^ Storehouses were required for storage of all the raw materials and goods necessary for building and fitting out a ship. The 1513 Storehouse was a rectangular building of brick construction c.50m x 10m and two stories high. It stood parallel to the river, on the river front, some 40 metres upstream of the (extant) Master Shipwright's House. (Both buildings are visible in Cleveley's painting of HMS St Albans, above.) The original Storehouse was added to, bit by bit over time, and in the early part of the 18th century it became the north range of a quadrangle of Storehouse buildings. This Storehouse complex, with cupola and clock atop the southern range, formed a prominent landmark for ships on this part of the river for over 200 years.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Orser. Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology. p. 166.

- ↑ Talling. London's Lost Rivers. p. 180.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 222.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 223.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 226.

- 1 2 Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 231.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 335.

- 1 2 Talling. London's Lost Rivers. p. 182.

- 1 2 Orser. Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology. p. 167.

- ↑ Summer Excursions in Kent. p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 336.

- 1 2 Kemp (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. p. 240.

- ↑ Lavery. The Ship of the Line. p. 14.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 370.

- ↑ Rodger. The Safeguard of the Sea. p. 377.

- ↑ Rodger. The Command of the Ocean. p. 46.

- 1 2 Browning. Peter the Great. pp. 108–9.

- 1 2 3 Kemp (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. p. 241.

- ↑ Rodger. The Command of the Ocean. p. 297.

- ↑ Lavery (ed.). The Line of Battle. p. 124.

- ↑ Lavery. Nelson's Navy. p. 224.

- 1 2 Winfield. British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792. pp. 366–8.

- ↑ Paine. Warships of the World to 1900. p. 23.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817. pp. 26, 39 & 52.

- ↑ Lavery. Nelson's Navy. p. 234.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Antiquary. p. 205.

- 1 2 Pevsner, The Buildings of England - London 2: South (Yale University Press, 1983 & 2002).

- ↑ English Heritage listing information

- ↑ "Build the Lenox". councilmeetings.lewisham.gov.uk. Lewisham Borough Council. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Lenox Project: a lasting legacy for Deptford". www.buildthelenox.org. The Lenox Project. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "Feasibility study report published by GLA". www.buildthelenox.org. The Lenox Project. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ Lavery. Nelson's Navy. p. 25.

- ↑ Rodger. The Command of the Ocean. p. 306.

- ↑ Lavery. Nelson's Navy. p. 24.

References

- The Antiquary. 1–2. London: E.W. Allen. 1871.

- Summer Excursions in Kent, Along the Banks of the Rivers Thames and Medway. London: W.S. Orr & Co. 1847.

- Peter Kemp, ed. (1976). The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. Oxford: Paladin. ISBN 0-586-08308-1.

- Robert Gardiner, ed. (1992). The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship 1650-1840. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-561-6.

- Browning, Oscar (1898). Peter the Great. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793-1815. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-521-7.

- Lavery, Brian (2003). The Ship of the Line: The Development of the Battlefleet 1650-1850. 1. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- Orser, Charles E. (2002). Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21544-2.

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Warships of the World to 1900. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-98414-7.

- Rodger, Nicholas (2004). The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain 660-1649. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-029724-9.

- Rodger, Nicholas (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-028896-4.

- Talling, Paul (2011). London's Lost Rivers. Random House. ISBN 978-1-84794-597-6.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-295-X.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84415-717-4.

External links

Coordinates: 51°29′11″N 0°01′39″W / 51.4865°N 0.0276°W