Fulvous whistling duck

| Fulvous whistling duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| An adult at the Wilhelma zoological and botanical gardens in Stuttgart | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Dendrocygna |

| Species: | D. bicolor |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendrocygna bicolor (Vieillot, 1816) | |

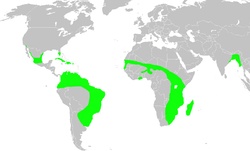

| |

| Approximate breeding range | |

The fulvous whistling duck or fulvous tree duck (Dendrocygna bicolor) is a whistling duck that breeds across the world's tropical regions in much of Mexico and South America, the West Indies, the southern US, sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent. It has mainly reddish brown plumage, long legs and a long grey bill, and shows a distinctive white band across its black tail in flight. Like other members of its ancient lineage, it has a whistling call which is given in flight or on the ground. The preferred habitat is shallow lakes, paddy fields or other wetlands with plentiful vegetation.

The nest, built from plant material and unlined, is placed among dense vegetation or in a tree hole. The typical clutch is around ten whitish eggs. The breeding adults, which pair for life, take turns to incubate, and the eggs hatch in 24–29 days. The downy grey ducklings leave the nest within a day or so of hatching, but the parents continue to protect them until they fledge around nine weeks later.

The fulvous whistling duck feeds in wetlands by day or night on seeds and other parts of plants. It is sometimes regarded as a pest of rice cultivation, and is also shot for food in parts of its range. Despite hunting, poisoning by pesticides and natural predation by mammals, birds and reptiles, the large numbers and huge range of this duck mean that it is classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Taxonomy

The whistling ducks, Dendrocygna, are a distinctive group of eight bird species within the duck, goose and swan family Anatidae, which are characterised by a hump-backed, long-necked appearance and the whistled flight calls that give them their English name.[2] They were an early split from the main duck lineage,[3] and were predominant in the Late Miocene before the subsequent extensive radiation of more modern forms in the Pliocene and later.[4] The fulvous whistling duck forms a superspecies with the wandering whistling duck. It has no recognised subspecies, although the birds in northern Mexico and the southern US have in the past been assigned to D. b. helva,[5] described as having paler and brighter underparts and a lighter crown than D. b. bicolor.[6]

The duck was first described by Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1789 and given the name Anas fulva but the name was "preoccupied," or already used, by Friedrich Christian Meuschen in 1787 for another species.[7][lower-alpha 1] This led to the next available name proposed by French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1816 from a Paraguayan specimen as Anas bicolor[9][lower-alpha 2] The whistling ducks were moved to their current genus, Dendrocygna, by British ornithologist William John Swainson in recognition of their differences from other ducks.[10] The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek dendron, "tree", and Latin cygnus, "swan",[11] and bicolor is Latin for "two-coloured".[12] "Fulvous" means reddish-yellow, and is derived from the Latin equivalent fulvus.[13] Old and regional names include large whistling teal,[5] brown tree duck, Mexican duck, squealer and Spanish cavalier.[14]

Description

The fulvous whistling duck is 45–53 cm (18–21 in) long; the male weighs 748–1,050 g (26.4–37.0 oz), and the female averages marginally lighter at 712–1,000 g (25.1–35.3 oz).[5] It is a long-legged duck, mainly golden-brown with a darker back and an obvious blackish line down the back of its neck. It has whitish stripes on its flanks, a long grey bill and grey legs. In flight, the wings are brown above and black below, with no white markings, and a white crescent on the rump contrasts with the black tail.[15][16] All plumages are fairly similar, but the female is slightly smaller and duller-plumaged than the male. The juvenile has paler underparts, and appears generally duller, especially on the flanks.[5] There is a complete wing moult after breeding, and birds then seek the cover of dense wetland vegetation while they are flightless. Body feathers may be moulted throughout the year, although each feather is replaced only once annually.[17]

These are noisy birds with a clear whistling kee-wee-ooo call given on the ground or in flight. Quarrelling birds also have a harsh repeated kee. In flight, the beating wings produce a dull sound.[18] The calls of males and females show differences in structure and an acoustic analysis on 59 captive birds demonstrated 100% accuracy in sexing when compared with molecular methods.[19]

Adult birds in Asia can be confused with the similar lesser whistling duck, although that species is smaller, has a blackish crown and lacks an obvious dark stripe down the back of the neck. Juvenile fulvous whistling ducks are very like young lesser whistling ducks, but the crown colour is still a distinction. Juvenile comb ducks are bulkier than whistling ducks and have a dark cap to the head. In South America and Africa, juvenile white-faced whistling ducks are separable from fulvous by their dark crowns, barred flanks and chestnut breasts.[18]

Distribution and habitat

The fulvous whistling duck has a very large range extending across four continents. It breeds in lowland South America from northern Argentina to Colombia and then up to the southern US and the West Indies. It is found in a broad belt across sub-Saharan Africa and down the east of the continent to South Africa and Madagascar. The Indian subcontinent is the Asian stronghold.[18]

It undertakes seasonal movements in response to the availability of water and food. African birds move southwards in the southern summer to breed and return north in the winter, and Asian populations are highly nomadic due to the variability of rainfall.[18] This species has strong colonising tendencies, having expanded its range in Mexico, the US and the West Indies in recent decades. Wandering birds can turn up far beyond the normal range, sometimes staying to nest, as in Morocco, Peru and Hawaii.[5]

The fulvous whistling duck is found in lowland marshes and swamps in open, flat country, and it avoids wooded areas. It is particularly attracted to wetlands with plenty of emergent vegetation, including rice fields.[18] It is not normally a mountain species, breeding in Venezuela, for example, only up 300 m (980 ft),[16] but the single Peruvian breeding record was at 4,080 m (13,390 ft).[5]

Behaviour

This species is usually found in small groups, although substantial flocks can form at favoured sites. It walks well, without waddling, and although it normally feeds by upending, it can dive if necessary.[18] It does not often perch in trees, unlike other whistling ducks. It flies at low altitude with slow wingbeats and trailing feet, in loose flocks rather than tight formation. It feeds during the day and at night in fairly large flocks, often with other whistling duck species, but rests or sleeps in smaller groups in the middle of the day.[17] They are noisy and display their aggression towards other individuals by throwing back their heads. Before taking off in alarm, they often shake their head sideways.[20]

A number of arthropod parasites have been recorded on this duck, including chewing mites of the families Philopteridae and Menoponidae,[21][22] feather mites and skin mites. Internal helminth parasites include roundworms, tapeworms and flukes. In a survey in Florida, all 30 ducks tested carried at least two helminth species, although none had blood parasites. Only one duck had no mites or lice.[23]

Breeding

Breeding coincides with the availability of water. In South America and South Africa, the main nesting period is December–February, in Nigeria it is July–December, and in North America mid-May–August.[5] In India, the breeding season is from June to October but peaking in July and August.[24] Fulvous whistling ducks show lifelong monogamy, although the courtship display is limited to some mutual head-dipping before mating and a short dance after copulation in which the birds raise their bodies side-by-side while treading water.[17]

Pairs may breed alone or in loose groups. In South Africa, nests may be within 50 m (160 ft) of each other, and breeding densities of up to 13.7 nests per square kilometre (35.5 per square mile) have been found in Louisiana. The nest, 19–26 cm (7.5–10.2 in) across, is made from plant leaves and stems and has little or no soft lining. It is usually built in dense vegetation and close to water,[5][16] but sometimes in tree holes. In India, the use of tree holes, and even the old nests of raptors or crows, is much more common than elsewhere.[18] Eggs are laid at roughly 24- to 36-hour intervals, starting before the nest is complete, resulting in some losses from the clutch. They are whitish and on average measure 53.4 mm × 40.7 mm (2.10 in × 1.60 in) and weigh 50.4 g (1.78 oz).[17] The clutch is usually around ten eggs, but other females sometimes lay into the nest, so 20 or more may be found on occasion.[5] Eggs may also be added to the nests of other species, like ruddy duck.[25]

Both sexes incubate, changing over once a day, with the male often taking the greater share of this duty. The eggs hatch in about 24–29 days,[5] The downy ducklings are grey, with paler upperparts,[17] and a white band on the neck,[14] and weigh 22–38 g (0.78–1.34 oz) within a day of hatching. Like all ducklings, they are precocial and leave the nest after a day or so, but the parents protect them until they fledge around nine weeks later.[5] Eggs and duckling may be preyed on by mammals, birds and reptiles, although one parent may try to distract a potential predator with a broken-wing display while the other adult leads the ducklings away.[17] Birds are sexually mature after one year, and the maximum known age is 6.5 years.[5]

In South Africa, a few records of hybridization with the white-faced whistling duck have been noted in the wild,[26][27] although in most parts of southern Africa, the two species breed at different times, bicolor during the dry season (April to September) and viduata during the rains (October to March).[28] Hybridization in captivity is more frequent but limited to other species in the genus Dendrocygna.[29][30]

Feeding

The fulvous whistling duck feeds in wetlands by day or night, often in mixed flocks with relatives such as white-faced or black-bellied whistling ducks. Its food is generally plant material, including seeds, bulbs, grasses and stems, but females may include animal items such as aquatic worms, molluscs and insects as they prepare for egg-laying, which may then comprise up to 4% of their diet. Ducklings may also eat a few insects. Foraging is by picking plant items while walking or swimming, by upending, or occasionally by diving to a depth of up to 1 m (3.3 ft). Favoured plants include water snowflake, aquatic ragweeds, bourgou millet, shama grass, Cape blue water lily, waxy-leaf nightshade, beakrush, flatsedge and polygonums. Rice is normally a small part of the diet, and a survey in Cuban rice fields found that the plants taken were mainly weeds growing with the crop. However, in a study in Louisiana, 25% of the diet of incubating females consisted of the cereal.[5]

Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates the population of the fulvous whistling duck to be from 1.3–1.5 million individuals.[1] This may be an underestimate since regional assessments suggest 1 million birds in the Americas, 1.1 million in Africa and at least 20,000 in South Asia.[17] Although the population appear to be declining, the decrease is not rapid enough to trigger the vulnerability criteria. The large numbers and huge breeding range mean that this duck is classified by the IUCN as being of Least Concern.[1] It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.[31]

The fulvous whistling duck has expanded its range in the West Indies, and into the southern US.[18] A series of invasions from South America and reaching the eastern US commenced around 1948, fueled by rice cultivation, and breeding was recorded in Cuba in 1964,[17] and Florida in 1965. Some Florida birds still winter in Cuba.[32] In Africa, it bred on the Cape Peninsula between 1940 and the 1960s. A survey of eighteen species which had colonised the area in recent decades found that most were wetland species that had used irrigated farmland as "stepping stones" across the arid country separating the peninsula from the breeding main range. However, the status of the two whistling duck species featured in the research is dubious since they are popular ornamental species, so their origin is unclear.[33]

Outside North America it is subject to hunting for food or because of its liking for rice, and persecution means that it is now rare in Madagascar. Pesticides used on rice fields may also have an adverse impact,[5] causing liver and breast muscle damage even at sub-lethal levels.[34]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 BirdLife International (2012). "Dendrocygna bicolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Madge & Burn (1988) p. 124.

- ↑ Feduccia (1999) p. 219.

- ↑ Agnolin, Federico; Tomassini, Rodrigo L (2012). "A fossil Dendrocygninae (Aves, Anatidae) from the early Pliocene of the Argentine Pampas and its paleobiogeographical implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 98: 191–201. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2012.06.001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hoyo, Josep del; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David A (eds.). "Fulvous Whistling-duck". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 17 March 2014. (subscription required)

- ↑ Wetmore, Alexander; Peters, James L (1922). "A new genus and four new subspecies of American birds". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 35: 41–46.

- ↑ Allen, J A; Richmond, C W; Brewster, W; Dwight, J. Jr; Merriam, C H; Ridgway, R; Stone, W (1908). "Fourteenth Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". Auk. 25: 343–399. doi:10.2307/4070558.

- ↑ Pollock, Andrew W (2012). "A-B" (PDF). Binomial and trinomial index to the Auk, 1884-1920. Also including the Nuttall Bulletin, 1876–1883, and the A.O.U. Check-List of North American Birds. 1: 253.

- ↑ Vieillot (1816) pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Swainson (1837) p. 365.

- ↑ Jobling (2010) pp. 128,133.

- ↑ Jobling (2010) p. 72.

- ↑ "Fulvous". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 March 2014.(subscription required)

- 1 2 Phillips (1922) pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Barlow et al. (1997) p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Hilty (2003) p. 195.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kear (2005) pp. 199–202.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Madge & Burn (1988) pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Volodin, Ilya; Kaiser, Martin; Matrosova, Vera; Volodina, Elena; Klenova, Anna; Filatova, Olga; Kholodova, Marina (2009). "The technique of noninvasive distant sexing for four monomorphic Dendrocygna whistling duck species by their loud whistles" (PDF). Bioacoustics. 18: 277–290. doi:10.1080/09524622.2009.9753606.

- ↑ Johnsgard (1965) pp. 16-20

- ↑ McDaniel, Burruss; Tuff, Donald; Bolen, Eric (1966). "External parasites of the Black-bellied Tree Duck and other dendrocygnids". The Wilson Bulletin. 78 (4): 462–468. JSTOR 4159536.

- ↑ Arnold, Don C (2006). "Review of the genus Acidoproctus (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera: Philopteridae), with description of a new species". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 79 (3): 272–282. JSTOR 25086333. doi:10.2317/0509.26.1.

- ↑ Forrester, Donald J; Kinsella, John M; Mertins, James W; Price, Roger D; Turnbull, Richard E (1994). "Parasitic helminths and arthropods of Fulvous Whistling-Ducks (Dendrocygna bicolor) in Southern Florida" (PDF). Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 61 (1): 84–88.

- ↑ Ali & Ripley (1978) pp. 139-141.

- ↑ Shields, A M (1899). "Nesting of the Fulvous Tree Duck". Cooper Ornithological Society. 1 (1): 9–11. JSTOR 1360784. doi:10.2307/1360784.

- ↑ Harebottle, Doug; Vanderwalt, Brian (2014). "Hybridisation between White-faced and Fulvous Ducks in the wild: further evidence from South Africa." (PDF). Ornithological Observations. 5: 17–21.

- ↑ Clark, A (1974). "Hybrid Dendrocygna viduata x Dendrocygna bicolor". Ostrich. 45: 255. doi:10.1080/00306525.1974.9634068.

- ↑ Siegfried, W Roy (1973). "Morphology and ecology of the southern African whistling ducks (Dendrocygna)" (PDF). Auk. 90 (1): 198–201.

- ↑ Kear (2005) p. 188.

- ↑ Johnsgard, Paul A (1960). "Hybridization in the Anatidae and its taxonomic implications" (PDF). Condor. 62 (1): 25–33. doi:10.2307/1365656.

- ↑ "Annex 2: Waterbird species to which the Agreement applies" (PDF). Agreement on the conservation of African-Eurasian migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). AEWA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Turnbull, Richard E; Johnson, Fred A; Brakhage, David H (1989). "Status, distribution, and foods of Fulvous Whistling-Ducks in South Florida". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 53 (4): 1046–1051. JSTOR 3809607. doi:10.2307/3809607.

- ↑ Hockey, Philip A R; Midgley, Guy F (2009). "Avian range changes and climate change: a cautionary tale from the Cape Peninsula". Ostrich. 80 (1): 29–34. doi:10.2989/OSTRICH.2009.80.1.4.762.

- ↑ Turnbull, Richard E; Johnson, Fred A; Hernandez, Maria de los A; Wheeler, Willis B; Toth, John P (1989). "Pesticide residues in Fulvous Whistling-Ducks from South Florida". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 53 (4): 1052–1057. JSTOR 3809608. doi:10.2307/3809608.

Cited texts

- Ali, Salim; Ripley, Dillon S (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Barlow, Clive; Wacher, Tim; Disley, Tony (1997). A Field Guide to birds of The Gambia and Senegal. Boroughbridge, Sussex: Pica Press. ISBN 1-873403-32-1.

- Feduccia, Alan (1999). The Origin and Evolution of Birds. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07861-9.

- Hilty, Steven L (2003). Birds of Venezuela. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Johnsgard, Paul (1965). Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior. Ithaca, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates.

- Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854645-0.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Wildfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese and Swans of the World (Helm Identification Guides). London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7470-2201-1.

- Phillips, John Charles (1922). A Natural History of the Ducks. 1. Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin.

- Swainson, William (1837). On the Natural History and Classification of Birds. 2. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

- Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1816). Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 5. Paris: Deterville.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dendrocygna bicolor. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Dendrocygna bicolor |

- Fulvous Whistling-duck videos at the Internet Bird Collection

- Tribe Dendrocygnini (Whistling or Tree Ducks) from Johnsgard, Paul A. Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

- Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Calls at Xeno-canto