Delaware and Hudson Canal

| Delaware and Hudson Canal | |

|---|---|

|

A remaining section of the canal in Sullivan County, NY, used as a linear park | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 108 miles (174 km) |

| Locks | 108 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 1,075 ft (328 m) |

| Status | Closed, partially infilled |

| Navigation authority | |

|

Delaware and Hudson Canal | |

| NRHP Reference # | 68000051[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 24, 1968[1] |

| Designated NHL | November 24, 1968[2] |

| History | |

| Original owner | Delaware and Hudson Canal Company |

| Construction began | 1825 |

| Date of first use | 1828 |

| Date closed | 1902 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Honesdale, PA |

| End point | Kingston, NY |

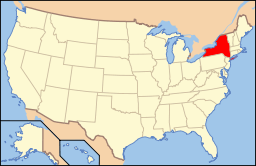

The Delaware and Hudson Canal was the first venture of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, which would later build the Delaware and Hudson Railway. Between 1828 and 1899, the canal's barges carried anthracite coal from the mines of Northeastern Pennsylvania to the Hudson River and thence to market in New York City.

Construction of the canal involved some major feats of civil engineering, and led to the development of some new technologies, particularly in rail transport. Its operation stimulated the city's growth and encouraged settlement in the sparsely populated region. Unlike many other canals of that era, the canal remained a profitable private operation for most of its existence.

For these reasons, the canal was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1968.[2]

The canal was abandoned in the early 20th century, and much of it was subsequently drained and filled. A few fragments remain in New York and Pennsylvania, and are in use as parks and historic sites.

History

Before the canal

In the early 19th century, Philadelphia businessman William Wurts often would leave his affairs aside for weeks at a time to explore the then-sparsely populated northeastern region of the state. He began noticing, mapping, and researching blackish rock outcroppings, becoming the first explorer of the anthracite fields that have since become known as the Coal Region. He believed they could be a valuable energy source, and brought samples back to Philadelphia for testing.[3]

Eventually, he convinced his brothers Charles and Maurice to come along with him and see for themselves. Starting in 1812, they began buying and mining large tracts of inexpensive land. They were able to extract several tons of anthracite at a time, but lost most of what they tried to bring back to Philadelphia due to the treacherous waterways that were the main method of transportation in the interior. While the southern reaches of the Coal Region were already beginning to supply Philadelphia, they realized that the areas they had been exploring and mining were well-positioned to deliver coal to New York City, which had experienced an energy crunch after the War of 1812, when restrictions were placed on the import of British coal. Inspired by the new and successful Erie Canal, they envisioned a canal of their own from Pennsylvania to New York, through the narrow valley between the Shawangunk Ridge and the Catskill Mountains, to the Hudson River near Kingston, a route followed by the Old Mine Road, America's first long-distance transportation route.[3]

After several years of lobbying by the Wurtses, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company was chartered by separate laws in the state of New York and commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1823, allowing William Wurts and his brother Maurice to construct the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The New York law, passed April 23, 1823, incorporated "The President, Managers and Company of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company", and the Pennsylvania law, passed March 13 of the same year, authorized the company "To Improve the Navigation of the Lackawaxen River". The company hired Benjamin Wright, who had engineered the Erie Canal, and his assistant John B. Jervis to survey and plan a route. A primary challenge was the 600-foot (183 m) elevation difference between the Delaware River at Lackawaxen and the Hudson at Rondout. Wright's initial estimated cost of $1.2 million was later revised to $1.6 million (in 1825 dollars).[3]

To attract investment, the brothers arranged for a demonstration of anthracite at a Wall Street coffeehouse in January 1825. The reaction was enthusiastic, and the stock oversubscribed within hours.

Construction

Ground was broken on July 13 of that year. After three years of labor by 2,500 men, the canal was opened to navigation in October 1828. It began at Rondout Creek at an area later known as Creeklocks, between Kingston (where the creek fed into the Hudson River) and Rosendale. From there it proceeded southwest alongside Rondout Creek to Ellenville, continuing through the valley of the Sandburg Creek, Homowack Kill, Basha Kill and Neversink River to Port Jervis on the Delaware River. From there the canal ran northwest on the New York side of the Delaware River, crossing into Pennsylvania at Lackawaxen and running on the north bank of the Lackawaxen River to Honesdale.[3]

To get the anthracite from the Wurts' mine in the Moosic Mountains near Carbondale to the canal at Honesdale, the canal company built the Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania authorized its construction on April 8, 1826. On August 8, 1829, the D&H's first locomotive, the Stourbridge Lion, made history as the first locomotive to run on rails in the United States.

Success and decline

Business took off as the Wurtses had anticipated, and in 1832 the canal carried 90,000 tons (81,000 tonnes) of coal and three million board-feet (7,080 m³) of lumber. The company invested the profits in improving the canal, making it deeper so larger barges could be used.[3]

In 1850, the Pennsylvania Coal Company constructed its own gravity railroad from the coal fields to the port at Hawley and the canal enjoyed increased traffic, carrying over 300,000 tons of PCC coal in the first season. However, the relationship between the two companies soured after the canal attempted to raise tolls under the argument that canal improvements had reduced costs for the PCC. The dispute led to the courts and was decided in 1863, but by that time the Erie Railroad constructed its extension to Hawley and the PCC moved its shipments to the railroad.[4]

The D&H was also developing railroads, a technology that was continuing to improve and supplant canal transportation at the time, to extend its reach into other Northeastern markets. The D&H also extended its gravity railroad from Carbondale deeper into the coal fields and expanded its capacity. By the time Maurice Wurts died in 1854, the company was reporting profits of 10-24% annually and had paid off its original debt to both states.[3]

The completion of the Erie Railroad through the Delaware Valley in 1848 and its branch to Hawley in 1863 began the end of the canal's days, although it continued to be very successful through the 1870s and '80s. Throughout the rest of the century, canals were perceived as quaint relics of pre-industrial times and began yielding to rail across the country. In 1898, the Delaware and Hudson finally joined them, carrying its last loads from Honesdale to Kingston, as rail could now carry coal more directly to the city, across New Jersey rather than via Kingston. The following year the company dropped the "Canal" from its name, the states authorizing it to abandon the canal if it deemed it suitable and concentrate on its rail interests, which it did.[3]

Post-closure

After the end of the 1898 season, the company opened all the waste weirs and drained the canal. Catskill rail magnate Samuel Coykendall purchased the canal the next summer, reportedly to benefit the Ramapo Water Company for use as a water supply resource [5] But that never came to pass. Instead, Coykendall used the northernmost section, from Rondout to Kingston, to transport Rosendale cement and other general merchandise to the river until abandoning that business in 1904.[6] The canal was never used again.

As the 20th century began, the company used some of the canal right-of-way for its expanding rail operations; some of the rest was sold to various private companies, mainly other, smaller railroads.[3] Developing communities along the route also filled it in as necessary to expand their own neighborhoods, or for safety reasons as when a Port Jervis man supposedly drowned in 1900.[7]

In the early 21st century residents of the town of Deerpark, north of Port Jervis, complained that the canal had been leaking water and causing flooding in the neighborhoods near Cuddebackville in recent years. Orange County, which maintains it in that area, met with town officials and local residents to discuss possible solutions.[8]

Preservation as historic site

The ruins of the canal and its associated structures remained standing. The Delaware & Hudson Canal Historical Society was formed in 1967;[9] its museum has an extensive education program and hosts hundreds of area students each season. The Neversink Valley Area Museum was formed in Orange County New York in 1968 and the National Park Service recognized the canal site in Orange County as a National Historic Landmark.[2] In 1969, New York's Sullivan County bought a 4-acre (16,000 m2) portion to develop as a park.[10] Many other buildings and sites associated with the canal have been added to the National Register of Historic Places and state and local landmark lists.

Canal

The finished canal ran 108 miles (174 km), from Honesdale to Kingston (counting the tidewater portions of the Rondout where the canal joined the creek at Eddyville). Its 108 locks took it over elevation changes totaling 1,075 feet (328 m), more than the Erie Canal's 675 feet (206 m).[11] The channel was four feet (122 cm) deep (eventually increased to six feet (2 m)) by 32 feet (10 m) wide. It was crossed by 137 bridges and had 26 dams, basins and reservoirs.[12] Originally it crossed the four rivers along its course — the Lackawaxen, Delaware, Neversink and Rondout Creek — via slackwater dams. Aqueducts were built over the rivers to replace them by John Roebling in the 1840s, cutting a few days from canal travel time and reducing accidents that were occurring at the Delaware crossing with loggers rafting their harvest downstream.

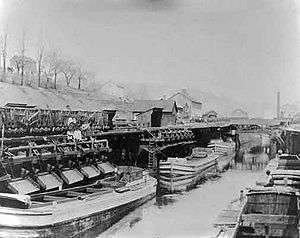

Barges were pulled by mules along the adjacent towpath, a power source employed even after the development of steam engines, since the bow wave from a faster steamboat would have damaged the channel.[6] Children were often hired to lead the mules at first; in the canal's later years grown men were employed. They had to walk 15–20 miles (24–32 km) a day, pump out the barges and tend the animals. For this they were paid about $3 a month.[13]

The canal was divided into three sections for operational purposes: the Lackawaxen, from Honesdale to the Delaware; the Delaware, along the river from there to Port Jervis; and then the Neversink, from Port Jervis to Kingston. A trip along its length took, initially, a week. It was closed on Sundays,[6] and would suspend operations each winter when the canal froze up or was likely to.

Its primary business was the transport of coal and lumber from the interior to the river. There was little traffic to Pennsylvania other than empty barges. The company tried offering passenger service at one point, and Washington Irving, a friend of Hone's, made the trip in the 1840s, but it was ultimately given up as unprofitable.

Legacy

Besides its historical firsts, the canal's most significant impact was to stimulate the growth of New York City along with the other anthracite canals. Fueled by the cheap and plentiful coal barged up the canal and down the river, the city was able to develop and industrialize at the same pace as other Eastern cities. There would be other benefits to the city as well. The company's first president, Philip Hone, served a term as the city's mayor during the canal's construction. Later, John Roebling's experience building the canal served him well in designing the Brooklyn Bridge.

On the Pennsylvania end, the interior anthracite regions were able to grow and develop from the rough wilderness they had been when William Wurts traveled them and mapped the coal deposits. The viability of its anthracite led to other markets opening up, sustaining the region economically well into the 20th century.

Along its route, the canal created many small boomtowns at frequent stops. Many towns took their names from canal executives. Honesdale took its name from Philip Hone, the company's first president. The village of Peenpack, New York, renamed itself Port Jervis after the engineer shortly after incorporating in 1853. Further along, the Wurtses are remembered by Wurtsboro, New York. A number of other New York communities with "port" in their name (Phillipsport, Port Orange and Port Jackson, now Accord) reflect their origins as canal towns. Summitville in turn takes its name from being the highest point along the canal route.

As automobiles began to displace the railroads that had once done the same to the canal, its corridor and towpath saw new life as highway routes. US 6 and PA 590 follow part of the route between Honesdale and Hawley, with 590 running along the towpath[7] and now-dry bed as it continues east along the Lackawaxen. The New York section of US 209 links the same communities in that state as the canal did, and intersects or runs closely parallel to its remnants in several areas. Within towns, Canal Street follows the route in Port Jervis, as does Towpath Road in Ellenville and the Town of Wawarsing.

The canal led to improvements in other technologies as well. The Rosendale cement discovered while excavating the canal bed near that town in 1825 would not only provide the canal itself with a cheap building material but created an industry that sustained the region for some time.[15] Jervis turned his expertise to designing locomotives, and the 4-2-0 type is commonly called the "Jervis" in his honor.

The canal today

Following its National Historic Landmark designation, interest grew in preserving what remained of the canal in the late 1960s. The canal, its infrastructure and associated buildings survive in many areas along its length.

Pennsylvania

- Honesdale: The terminal basin site has a state historical marker, and traces of the gravity railroad route can still be seen. Some stretches of the bed are visible along Routes 6 and 590 as they approach town from the south.

- Lower Lackawaxen valley: Route 590 follows the bed and towpath in some areas, and Towpath Road picks up the route in Pike County's Lackawaxen Township.

- Lackawaxen and Barryville, New York: Roebling's Delaware Aqueduct, the only one of the four on the canal still in use today and a National Civil Engineering Landmark as the oldest wire suspension bridge in the United States, was restored by the National Park Service and still carries automobiles over the Delaware between the two states. Just north of the bridge, a former company office has been converted into a bed and breakfast.

New York

- Port Jervis: A portion of the old towpath near Park Avenue (NY 42/97) on the north end of the city has been paved and is used as a city park. Canal Street is the former bed, now filled. Fort Decker, the oldest building in the city, was used to house canal workers during construction.

- Cuddebackville: Orange County has developed a county park along the Neversink here, just south of Hamilton Bicentennial Elementary School off Route 209. The footings of Roebling's aqueduct still stand, and a portion of the bed and towpath persist in the adjacent woods. The Neversink Valley Museum, also located in the park, has some exhibits related to the canal.[16]

- Town of Mamakating: Sullivan County maintains the largest remaining fragment of the canal, some of which is still wet, as Delaware and Hudson Canal Linear Park. Hiking, cross-country skiing and jogging and fishing are permitted along the 3.5 mile (5.6-km), 45 acre (18 ha) section near Summitville, north of Wurtsboro. Much of the land is beginning to return to its natural state due to the long years since the canal was abandoned. Some locks and other structures can be found from two different access points along Route 209[10]

- Woodridge: Silver Lake Dam, some distance from the canal mainline, was built during the 1840s expansion to provide a reliable reservoir for the summit section of the canal.

- Ellenville: Towpath Road follows the old route from Route 209 south of the village to Canal Street (NY 52) within it, and a wet section of the bed remains just north of Canal in the woods off Berme Road just opposite the village's firehouse.

- Napanoch: A dry section of bed is located between Eastern Correctional Facility and the Rondout, right next to the old Ontario and Western railroad station.

- High Falls: Several old locks are located here, near the site of the last of Roebling's aqueducts, as well as the canal museum. The downtown area was heavily developed as a result of the canal.

- Rosendale The empty bed of the canal runs parallel to NY 213 between its crossing of the Rondout and Rosendale Village.

- Creeklocks: The northernmost lock still exists, as does the final section before the canal flowed into the Rondout.

- Kingston: The former port of Rondout, the north end of the barges' route, has been recognized as the Rondout-West Strand Historic District and revitalized, still in use as a waterfront and a draw for visitors to the city.

See also

- Morris Canal

- Delaware and Raritan Canal

- Delaware and Hudson Canal Gravity Railroad Shops

- List of canals in New York

- List of canals in the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Pike County, Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Wayne County, Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Orange County, New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sullivan County, New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Ulster County, New York

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 "Delaware and Hudson Canal". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Whitford, Noble (1905). "Chapter XX: The Delaware and Hudson Canal.". History of the Canal System of the State of New York. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Roth, Philip (1997). Of Pulleys and Ropes and Gear. Honesdale, PA: Wayne County Historical Society. pp. 41–44. ISBN 0-9659540-0-5.

- ↑ "Ramapo's Big Purchase" (PDF). The New York Times. August 26, 1899. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- 1 2 3 Adams, Arthur (1996). The Hudson Through the Years. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. pp. 73–78. ISBN 0-8232-1677-2. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- 1 2 Kirby, David (2002-08-25). "A Main Artery of the 1800s". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

Much of the D & H in Port Jervis was filled in around 1900, after a drunken city elder supposedly toppled in and drowned.

- ↑ Sacco, Stephen (May 29, 2009). "Officials to discuss possible solutions for crumbling condition of D&H canal". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ↑ "D & H Canal Historical Society, High Falls, NY". Retrieved 2007-10-23.. The Society's D&H Canal Museum and Five Lock's Walk (a National Historic Landmark) operate from May through October. Visitors can view a working lock model and retrace the steps of the historic "canawlers" on the recently restored 1/2 mile towpath trail which features five stone locks and lock tender's cottages. }

- 1 2 "Delaware & Hudson Canal Linear Park". Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ Rinaldi, Thomas (2006). Hudson Valley Ruins: Forgotten Landmarks of an American Landscape. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. p. 125. ISBN 1-58465-598-4. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

The D & H accomplished a greater change in elevation — 1,075 feet versus the Erie's 675 ..."

- ↑ "D & H Canal Story". April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Osterberg, Matthew (2002). The Delaware & Hudson Canal and the Gravity Railroad. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 0-7385-1087-4. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Theodore Robinson, Pioneer of American Impressionism

- ↑ Rinaldi, op. cit., 129.

- ↑ "D&H Canal Park". Retrieved 2007-10-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Delaware and Hudson Canal. |

- Neversink Valley Area Museum, located in Cuddebackville at canal park

- Delaware and Hudson Linear Park

- D&H Canal Park

- Route of the D&H Canal

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-1, "Delaware & Hudson Canal, Delaware Aqueduct, spanning Delaware River at Lackawaxen, Pike County, PA", 56 photos, 1 color transparency, 8 measured drawings, 16 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HAER No. NY-205, "Delaware & Hudson Canal, Delaware Aqueduct Toll House, Minisink Ford, Sullivan County, NY", 10 photos, 3 measured drawings, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. NY-262, "Delaware & Hudson Canal, Survey of Locks 70-72, Downstream from Delaware Aqueduct between Delaware River & Route 97, Minisink Ford, Sullivan County, NY", 1 measured drawing

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-4383, "De Motte House, Delaware & Hudson Canal, High Falls, Ulster County, NY", 1 photo

- Wurts family papers at Hagley Museum and Library offer an opportunity to examine in detail the early history of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company

Coordinates: 41°36′26″N 74°26′53″W / 41.60722°N 74.44806°W