Battle of Stalingrad

| Battle of Stalingrad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

Soviet soldier waving the Red Banner over the central plaza of Stalingrad in 1943. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initial:

At the time of the Soviet counter-offensive: |

Initial:

At the time of the Soviet counteroffensive: | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| See casualties section |

| ||||||

Location of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) within modern Russia | |||||||

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943)[8][9][10][11] was a major battle of World War II in which Nazi Germany and its allies fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) in Southern Russia.

Marked by fierce close quarters combat and direct assaults on civilians by air raids, it is often regarded as one of the single largest (nearly 2.2 million personnel) and bloodiest (1.7–2 million wounded, killed or captured) battles in the history of warfare.[12] It was an extremely costly defeat for German forces, and the Army High Command had to withdraw vast military forces from the West to replace their losses.[1]

The German offensive to capture Stalingrad began in August 1942, using the German 6th Army and elements of the 4th Panzer Army. The attack was supported by intensive Luftwaffe bombing that reduced much of the city to rubble. The fighting degenerated into house-to-house fighting, and both sides poured reinforcements into the city. By mid-November 1942, the Germans had pushed the Soviet defenders back at great cost into narrow zones along the west bank of the Volga River.

On 19 November 1942, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus, a two-pronged attack targeting the weaker Romanian and Hungarian armies protecting the German 6th Army's flanks.[13] The Axis forces on the flanks were overrun and the 6th Army was cut off and surrounded in the Stalingrad area. Adolf Hitler ordered that the army stay in Stalingrad and make no attempt to break out; instead, attempts were made to supply the army by air and to break the encirclement from the outside. Heavy fighting continued for another two months. By the beginning of February 1943, the Axis forces in Stalingrad had exhausted their ammunition and food. The remaining units of the 6th Army surrendered.[14]:932 The battle lasted five months, one week, and three days.

Historical background

By the spring of 1942, despite the failure of Operation Barbarossa to decisively defeat the Soviet Union in a single campaign, the Wehrmacht had captured vast expanses of territory, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic republics. Elsewhere, the war had been progressing well: the U-boat offensive in the Atlantic had been very successful and Rommel had just captured Tobruk.[15]:522 In the east, they had stabilized their front in a line running from Leningrad in the north to Rostov in the south. There were a number of salients, but these were not particularly threatening. Hitler was confident that he could master the Red Army after the winter of 1942, because even though Army Group Centre (Heeresgruppe Mitte) had suffered heavy losses west of Moscow the previous winter, 65% of Army Group Centre's infantry had not been engaged and had been rested and re-equipped. Neither Army Group North nor Army Group South had been particularly hard pressed over the winter.[16]:144 Stalin was expecting the main thrust of the German summer attacks to be directed against Moscow again.[1]:498

With the initial operations being very successful, the Germans decided that their summer campaign in 1942 would be directed at the southern parts of the Soviet Union. The initial objectives in the region around Stalingrad were the destruction of the industrial capacity of the city and the deployment of forces to block the Volga River. The river was a key route from the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea to central Russia. Its capture would disrupt commercial river traffic. The Germans cut the pipeline from the oilfields when they captured Rostov on 23 July. The capture of Stalingrad would make the delivery of Lend Lease supplies via the Persian Corridor much more difficult.[14]:909[17][18]:88

On 23 July 1942, Hitler personally rewrote the operational objectives for the 1942 campaign, greatly expanding them to include the occupation of the city of Stalingrad. Both sides began to attach propaganda value to the city based on it bearing the name of the leader of the Soviet Union. Hitler proclaimed that after Stalingrad's capture, its male citizens were to be killed and all women and children were to be deported because its population was "thoroughly communistic" and "especially dangerous".[19] It was assumed that the fall of the city would also firmly secure the northern and western flanks of the German armies as they advanced on Baku, with the aim of securing these strategic petroleum resources for Germany.[15]:528 The expansion of objectives was a significant factor in Germany's failure at Stalingrad, caused by German overconfidence and an underestimation of Soviet reserves.[20]

The Soviets realized that they were under tremendous constraints of time and resources and ordered that anyone strong enough to hold a rifle be sent to fight.[21]:94

Prelude

If I do not get the oil of Maikop and Grozny then I must finish [liquidieren; "kill off", "liquidate"] this war.— Adolf Hitler[15]:514

Army Group South was selected for a sprint forward through the southern Russian steppes into the Caucasus to capture the vital Soviet oil fields there. The planned summer offensive was code-named Fall Blau (Case Blue). It was to include the German 6th, 17th, 4th Panzer and 1st Panzer Armies. Army Group South had overrun the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1941. Poised in Eastern Ukraine, it was to spearhead the offensive.

Hitler intervened, however, ordering the Army Group to split in two. Army Group South (A), under the command of Wilhelm List, was to continue advancing south towards the Caucasus as planned with the 17th Army and First Panzer Army. Army Group South (B), including Friedrich Paulus's 6th Army and Hermann Hoth's 4th Panzer Army, was to move east towards the Volga and Stalingrad. Army Group B was commanded initially by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock and later by General Maximilian von Weichs.[14]:915

The start of Case Blue had been planned for late May 1942. A number of German and Romanian units that were to take part in Blau, however, were besieging Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula. Delays in ending the siege pushed back the start date for Blau several times, and the city did not fall until the end of June.

Operation Fridericus I by the Germans against the "Isium bulge", pinched off the Soviet salient in the Second Battle of Kharkov, and resulted in the envelopment of a large Soviet force between 17 May and 29 May. Similarly, Operation Wilhelm attacked Voltshansk on 13 June and Operation Fridericus attacked Kupiansk on 22 June.[22]

Blau finally opened as Army Group South began its attack into southern Russia on 28 June 1942. The German offensive started well. Soviet forces offered little resistance in the vast empty steppes and started streaming eastward. Several attempts to re-establish a defensive line failed when German units outflanked them. Two major pockets were formed and destroyed: the first, northeast of Kharkov, on 2 July, and a second, around Millerovo, Rostov Oblast, a week later. Meanwhile, the Hungarian 2nd Army and the German 4th Panzer Army had launched an assault on Voronezh, capturing the city on 5 July.

The initial advance of the 6th Army was so successful that Hitler intervened and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to join Army Group South (A) to the south. A massive traffic jam resulted when the 4th Panzer and the 1st Panzer both required the few roads in the area. Both armies were stopped dead while they attempted to clear the resulting mess of thousands of vehicles. The delay was long, and it is thought that it cost the advance at least one week. With the advance now slowed, Hitler changed his mind and reassigned the 4th Panzer Army back to the attack on Stalingrad.

By the end of July, the Germans had pushed the Soviets across the Don River. At this point, the Don and Volga Rivers were only 65 km (40 mi) apart, and the Germans left their main supply depots west of the Don, which had important implications later in the course of the battle. The Germans began using the armies of their Italian, Hungarian and Romanian allies to guard their left (northern) flank. The Italians won several accolades in official German communiques.[23][24][25][26] Sometimes they were held in little regard by the Germans, and were even accused of having low morale: in reality, the Italian divisions fought comparatively well, with the 3rd Mountain Infantry Division Ravenna and 5th Infantry Division Cosseria proving to have good morale, according to a German liaison officer[27] and being forced to retreat only after a massive armoured attack in which German reinforcements had failed to arrive in time, according to a German historian.[28] Indeed the Italians distinguished themselves in numerous battles, as in the battle of Nikolayevka.

On 25 July the Germans faced stiff resistance with a Soviet bridgehead west of Kalach. "We had had to pay a high cost in men and material...left on the Kalatch battlefield were numerous burnt-out or shot-up German tanks."[22]:33–34, 39–40

The Germans formed bridgeheads across the Don on 20 Aug. with the 295th and 76th Infantry Divisions, enabling the XIVth Panzer Corps "to thrust to the Volga north of Stalingrad." The German 6th Army was only a few dozen kilometers from Stalingrad. The 4th Panzer Army, ordered south on 13 July to block the Soviet retreat "weakened by the 17th Army and the 1st Panzer Army", had turned northwards to help take the city from the south.[22]:28, 30, 40, 48, 57

To the south, Army Group A was pushing far into the Caucasus, but their advance slowed as supply lines grew overextended. The two German army groups were not positioned to support one another due to the great distances involved.

After German intentions became clear in July 1942, Stalin appointed Marshal Andrey Yeryomenko as commander of the Southeastern Front on 1 August 1942. Yeryomenko and Commissar Nikita Khrushchev were tasked with planning the defense of Stalingrad.[29]:25, 48 The eastern border of Stalingrad was the wide River Volga, and over the river, additional Soviet units were deployed. These units became the newly formed 62nd Army, which Yeryomenko placed under the command of Lieutenant General Vasiliy Chuikov on 11 September 1942.[22]:80 The situation was extremely dire. When asked how he interpreted his task, he responded "We will defend the city or die in the attempt."[30]:127 The 62nd Army's mission was to defend Stalingrad at all costs. Chuikov's generalship during the battle earned him one of his two Hero of the Soviet Union awards.

Attack on Stalingrad

David Glantz indicated[31] that four hard-fought battles – collectively known as the Kotluban Operations – north of Stalingrad, where the Soviets made their greatest stand, decided Germany's fate before the Nazis ever set foot in the city itself, and were a turning point in the war. Beginning in late August, continuing in September and into October, the Soviets committed between two and four armies in hastily coordinated and poorly controlled attacks against the German's northern flank. The actions resulted in more than 200,000 Red Army casualties but did slow the German assault.

On 23 August the 6th Army reached the outskirts of Stalingrad in pursuit of the 62nd and 64th Armies, which had fallen back into the city. Kleist later said after the war:[32]

The capture of Stalingrad was subsidiary to the main aim. It was only of importance as a convenient place, in the bottleneck between Don and the Volga, where we could block an attack on our flank by Russian forces coming from the east. At the start, Stalingrad was no more than a name on the map to us.[32]

The Soviets had enough warning of the Germans' advance to ship grain, cattle, and railway cars across the Volga and out of harm's way but most civilian residents were not evacuated. This "harvest victory" left the city short of food even before the German attack began. Before the Heer reached the city itself, the Luftwaffe had rendered the River Volga, vital for bringing supplies into the city, unusable to Soviet shipping. Between 25 and 31 July, 32 Soviet ships were sunk, with another nine crippled.[33]:69

The battle began with the heavy bombing of the city by Generaloberst Wolfram von Richthofen's Luftflotte 4, which in the summer and autumn of 1942 was the single most powerful air formation in the world. Some 1,000 tons of bombs were dropped in 48 hours, more than in London at the height of the Blitz.[2]:122 Stalin refused to evacuate civilian population from the city, so when bombing began 400,000 civilians were trapped within city boundaries. The exact number of civilians killed during the course of the battle is unknown but was most likely very high. Around 40,000 were moved to Germany as slave workers, some fled the city during battle and small number evacuated by Soviets. In February 1943 only between 10,000 to 60,000 civilians were still alive in Stalingrad. Much of the city was quickly turned to rubble, although some factories continued production while workers joined in the fighting. The Stalingrad Tractor Factory continued to turn out T-34 tanks literally until German troops burst into the plant. The 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment was the only non-German unit[34] selected by the Wehrmacht to enter Stalingrad city during assault operations. It fought as part of the 100th Jäger Division.

Stalin rushed all available troops to the east bank of the Volga, some from as far away as Siberia. All the regular ferries were quickly destroyed by the Luftwaffe, which then targeted troop barges being towed slowly across the river by tugs.[29] It has been said that Stalin prevented civilians from leaving the city in the belief that their presence would encourage greater resistance from the city's defenders.[30]:106 Civilians, including women and children, were put to work building trenchworks and protective fortifications. A massive German air raid on 23 August caused a firestorm, killing hundreds and turning Stalingrad into a vast landscape of rubble and burnt ruins. Ninety percent of the living space in the Voroshilovskiy area was destroyed. Between 23 and 26 August, Soviet reports indicate 955 people were killed and another 1,181 wounded as a result of the bombing.[2]:73 Casualties of 40,000 were greatly exaggerated,[5]:188–89 and after 25 August, the Soviets did not record any civilian and military casualties as a result of air raids.[Note 4]

The Soviet Air Force, the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS), was swept aside by the Luftwaffe. The VVS bases in the immediate area lost 201 aircraft between 23 and 31 August, and despite meager reinforcements of some 100 aircraft in August, it was left with just 192 serviceable aircraft, 57 of which were fighters.[2]:74 The Soviets continued to pour aerial reinforcements into the Stalingrad area in late September, but continued to suffer appalling losses; the Luftwaffe had complete control of the skies.

The burden of the initial defense of the city fell on the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment,[30]:106 a unit made up mainly of young female volunteers who had no training for engaging ground targets. Despite this, and with no support available from other units, the AA gunners stayed at their posts and took on the advancing panzers. The German 16th Panzer Division reportedly had to fight the 1077th's gunners "shot for shot" until all 37 anti-aircraft guns were destroyed or overrun. The 16th Panzer was shocked to find that, due to Soviet manpower shortages, it had been fighting female soldiers.[30]:108[36] In the early stages of the battle, the NKVD organized poorly armed "Workers' militias" composed of civilians not directly involved in war production for immediate use in the battle. The civilians were often sent into battle without rifles.[30]:109 Staff and students from the local technical university formed a "tank destroyer" unit. They assembled tanks from leftover parts at the tractor factory. These tanks, unpainted and lacking gunsights, were driven directly from the factory floor to the front line. They could only be aimed at point-blank range through the gun barrel.[30]:110

By the end of August, Army Group South (B) had finally reached the Volga, north of Stalingrad. Another advance to the river south of the city followed, while the Soviets abandoned their Rossoshka position for the inner defensive ring west of Stalingrad. The wings of the 6th Army and the 4th Panzer Army met near Jablotchni along the Zaritza on 2 Sept.[22]:65 By 1 September, the Soviets could only reinforce and supply their forces in Stalingrad by perilous crossings of the Volga under constant bombardment by artillery and aircraft.

On 5 September, the Soviet 24th and 66th Armies organized a massive attack against XIV Panzer Corps. The Luftwaffe helped repulse the offensive by heavily attacking Soviet artillery positions and defensive lines. The Soviets were forced to withdraw at midday after only a few hours. Of the 120 tanks the Soviets had committed, 30 were lost to air attack.[2]:75

Soviet operations were constantly hampered by the Luftwaffe. On 18 September, the Soviet 1st Guards and 24th Army launched an offensive against VIII Army Corps at Kotluban. VIII. Fliegerkorps dispatched wave after wave of Stuka dive-bombers to prevent a breakthrough. The offensive was repulsed. The Stukas claimed 41 of the 106 Soviet tanks knocked out that morning, while escorting Bf 109s destroyed 77 Soviet aircraft.[2]:80 Amid the debris of the wrecked city, the Soviet 62nd and 64th Armies, which included the Soviet 13th Guards Rifle Division, anchored their defense lines with strongpoints in houses and factories.

Fighting within the ruined city was fierce and desperate. Lieutenant General Alexander Rodimtsev was in charge of the 13th Guards Rifle Division, and received one of two Heroes of the Soviet Union awarded during the battle for his actions. Stalin's Order No. 227 of 27 July 1942 decreed that all commanders who ordered unauthorized retreat would be subject to a military tribunal.[37] However, it was the NKVD that ordered the regular army and lectured them, on the need to show some guts. Through brutal coercion for self-sacrifice, thousands of deserters and presumed malingerers were captured or executed to discipline the troops. At Stalingrad, it is estimated that 14,000 soldiers of the Red Army were executed in order to keep the formation.[38] "Not a step back!" and "There is no land behind the Volga!" were the slogans. The Germans pushing forward into Stalingrad suffered heavy casualties.

Fighting in the city

By 12 September, at the time of their retreat into the city, the Soviet 62nd Army had been reduced to 90 tanks, 700 mortars and just 20,000 personnel.[30] The remaining tanks were used as immobile strongpoints within the city. The initial German attack attempted to take the city in a rush. One infantry division went after the Mamayev Kurgan hill, one attacked the central rail station and one attacked toward the central landing stage on the Volga.

Though initially successful, the German attacks stalled in the face of Soviet reinforcements brought in from across the Volga. The Soviet 13th Guards Rifle Division, assigned to counterattack at the Mamayev Kurgan and at Railway Station No. 1 suffered particularly heavy losses. Over 30 percent of its soldiers were killed in the first 24 hours, and just 320 out of the original 10,000 survived the entire battle. Both objectives were retaken, but only temporarily. The railway station changed hands 14 times in six hours. By the following evening, the 13th Guards Rifle Division had ceased to exist.

Combat raged for three days at the giant grain elevator in the south of the city. About fifty Red Army defenders, cut off from resupply, held the position for five days and fought off ten different assaults before running out of ammunition and water. Only forty dead Soviet fighters were found, though the Germans had thought there were many more due to the intensity of resistance. The Soviets burned large amounts of grain during their retreat in order to deny the enemy food. Paulus chose the grain elevator and silos as the symbol of Stalingrad for a patch he was having designed to commemorate the battle after a German victory.

German military doctrine was based on the principle of combined-arms teams and close cooperation between tanks, infantry, engineers, artillery and ground-attack aircraft. Some Soviet commanders adopted the tactic of always keeping their front-line positions as close to the Germans as physically possible; Chuikov called this "hugging" the Germans. This slowed the German advance and reduced the effectiveness of the German advantage in supporting fire.[39]

The Red Army gradually adopted a strategy to hold for as long as possible all the ground in the city. Thus, they converted multi-floored apartment blocks, factories, warehouses, street corner residences and office buildings into a series of well defended strongpoints with small 5–10 man units.[39] Manpower in the city was constantly refreshed by bringing additional troops over the Volga. When a position was lost, an immediate attempt was usually made to re-take it with fresh forces.

Bitter fighting raged for every ruin, street, factory, house, basement, and staircase. Even the sewers were the sites of firefights. The Germans, calling this unseen urban warfare Rattenkrieg ("Rat War"),[40] bitterly joked about capturing the kitchen but still fighting for the living room and the bedroom. Buildings had to be cleared room by room through the bombed-out debris of residential neighborhoods, office blocks, basements and apartment high-rises. Some of the taller buildings, blasted into roofless shells by earlier German aerial bombardment, saw floor-by-floor, close quarters combat, with the Germans and Soviets on alternate levels, firing at each other through holes in the floors.[39]

Fighting on and around Mamayev Kurgan, a prominent hill above the city, was particularly merciless; indeed, the position changed hands many times.[22]:67–68[29]:?[41]

In another part of the city, a Soviet platoon under the command of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov fortified a four-story building that oversaw a square 300 meters from the river bank, later called Pavlov's House. The soldiers surrounded it with minefields, set up machine-gun positions at the windows and breached the walls in the basement for better communications.[30] The soldiers found about ten Soviet civilians hiding in the basement. They were not relieved, and not significantly reinforced, for two months. The building was labeled Festung ("Fortress") on German maps. Sgt. Pavlov was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union for his actions.

The Germans made slow but steady progress through the city. Positions were taken individually, but the Germans were never able to capture the key crossing points along the river bank. By 27 Sept. the Germans occupied the southern portion of the city, but the Soviets held the center and northern part. Most importantly, the Soviets controlled the ferries to their supplies on the east bank of the Volga.[22]:68

The Germans used airpower, tanks and heavy artillery to clear the city with varying degrees of success. Toward the end of the battle, the gigantic railroad gun nicknamed Dora was brought into the area. The Soviets built up a large number of artillery batteries on the east bank of the Volga. This artillery was able to bombard the German positions or at least to provide counter-battery fire.

Snipers on both sides used the ruins to inflict casualties. The most famous Soviet sniper in Stalingrad was Vasily Zaytsev,[42] with 225 confirmed kills during the battle. Targets were often soldiers bringing up food or water to forward positions. Artillery spotters were an especially prized target for snipers.

A significant historical debate concerns the degree of terror in the Red Army. The British historian Antony Beevor noted the "sinister" message from the Stalingrad Front's Political Department on 8 October 1942 that: "The defeatist mood is almost eliminated and the number of treasonous incidents is getting lower" as an example of the sort of coercion Red Army soldiers experienced under the Special Detachments (later to be renamed SMERSH).[43]:154–68 On the other hand, Beevor noted the often extraordinary bravery of the Soviet soldiers in a battle that was only comparable to Verdun, and argued that terror alone cannot explain such self-sacrifice.[30]:154–68 Richard Overy addresses the question of just how important the Red Army's coercive methods were to the Soviet war effort compared with other motivational factors such as hatred for the enemy. He argues that, though it is "easy to argue that from the summer of 1942 the Soviet army fought because it was forced to fight," to concentrate solely on coercion is nonetheless to "distort our view of the Soviet war effort."[44] After conducting hundreds of interviews with Soviet veterans on the subject of terror on the Eastern Front – and specifically about Order No. 227 ("Not a step back!") at Stalingrad – Catherine Merridale notes that, seemingly paradoxically, "their response was frequently relief."[45] Infantryman Lev Lvovich's explanation, for example, is typical for these interviews; as he recalls, "[i]t was a necessary and important step. We all knew where we stood after we had heard it. And we all – it's true – felt better. Yes, we felt better."[46]

Many women fought on the Soviet side, or were under fire. As General Chuikov acknowledged, "Remembering the defence of Stalingrad, I can't overlook the very important question ... about the role of women in war, in the rear, but also at the front. Equally with men they bore all the burdens of combat life and together with us men, they went all the way to Berlin."[47] At the beginning of the battle there were 75,000 women and girls from the Stalingrad area who had finished military or medical training, and all of whom were to serve in the battle.[48] Women staffed a great many of the anti-aircraft batteries that fought not only the Luftwaffe but German tanks.[49] Soviet nurses not only treated wounded personnel under fire but were involved in the highly dangerous work of bringing wounded soldiers back to the hospitals under enemy fire.[50] Many of the Soviet wireless and telephone operators were women who often suffered heavy casualties when their command posts came under fire.[51] Though women were not usually trained as infantry, many Soviet women fought as machine gunners, mortar operators, and scouts.[52] Women were also snipers at Stalingrad.[53] Three air regiments at Stalingrad were entirely female.[52] At least three women won the title Hero of the Soviet Union while driving tanks at Stalingrad.[54]

For both Stalin and Hitler, Stalingrad became a matter of prestige far beyond its strategic significance.[55] The Soviet command moved units from the Red Army strategic reserve in the Moscow area to the lower Volga, and transferred aircraft from the entire country to the Stalingrad region.

The strain on both military commanders was immense: Paulus developed an uncontrollable tic in his eye, which eventually afflicted the left side of his face, while Chuikov experienced an outbreak of eczema that required him to have his hands completely bandaged. Troops on both sides faced the constant strain of close-range combat.[56]

Air attacks

Determined to crush Soviet resistance, Luftflotte 4's Stukawaffe flew 900 individual sorties against Soviet positions at the Dzerzhinskiy Tractor Factory on 5 October. Several Soviet regiments were wiped out; the entire staff of the Soviet 339th Infantry Regiment was killed the following morning during an air raid.[2]:83

In mid-October, the Luftwaffe intensified its efforts against remaining Red Army positions holding the west bank. Luftflotte 4 flew 2,000 sorties on 14 October and 550 t (610 short tons) of bombs were dropped while German infantry surrounded the three factories. Stukageschwader 1, 2, and 77 had largely silenced Soviet artillery on the eastern bank of the Volga before turning their attention to the shipping that was once again trying to reinforce the narrowing Soviet pockets of resistance. The 62nd Army had been cut in two, and, due to intensive air attack on its supply ferries, was receiving much less material support. With the Soviets forced into a 1-kilometre (1,000-yard) strip of land on the western bank of the Volga, over 1,208 Stuka missions were flown in an effort to eliminate them.[2]:84

The Luftwaffe retained air superiority into November and Soviet daytime aerial resistance was nonexistent. However, the combination of constant air support operations on the German side and the Soviet surrender of the daytime skies began to affect the strategic balance in the air. After flying 20,000 individual sorties, the Luftwaffe's original strength of 1,600 serviceable aircraft had fallen to 950. The Kampfwaffe (bomber force) had been hardest hit, having only 232 out of a force of 480 left.[5]:95 The VVS remained qualitatively inferior, but by the time of the Soviet counter-offensive, the VVS had reached numerical superiority.

The Soviet bomber force, the Aviatsiya Dal'nego Deystviya (Long Range Aviation; ADD), having taken crippling losses over the past 18 months, was restricted to flying at night. The Soviets flew 11,317 night sorties over Stalingrad and the Don-bend sector between 17 July and 19 November. These raids caused little damage and were of nuisance value only.[2]:82[57]:265

On 8 November, substantial units from Luftflotte 4 were withdrawn to combat the Allied landings in North Africa. The German air arm found itself spread thinly across Europe, struggling to maintain its strength in the other southern sectors of the Soviet-German front.[Note 5] The Soviets began receiving material assistance from the American government under the Lend-Lease program. During the last quarter of 1942, the U.S. sent the Soviet Union 45,000 t (50,000 short tons) of explosives and 230,000 t (250,000 short tons) of aviation fuel.[58]:404

As historian Chris Bellamy notes, the Germans paid a high strategic price for the aircraft sent into Stalingrad: the Luftwaffe was forced to divert much of its air strength away from the oil-rich Caucasus, which had been Hitler's original grand-strategic objective.[59]

Germans reach the Volga

After three months of slow advance, the Germans finally reached the river banks, capturing 90% of the ruined city and splitting the remaining Soviet forces into two narrow pockets. Ice floes on the Volga now prevented boats and tugs from supplying the Soviet defenders. Nevertheless, the fighting, especially on the slopes of Mamayev Kurgan and inside the factory area in the northern part of the city, continued.

Soviet counter-offensives

Recognizing that German troops were ill prepared for offensive operations during the winter of 1942, and that most of them were redeployed elsewhere on the southern sector of the Eastern Front, the Stavka decided to conduct a number of offensive operations between 19 November 1942 and 2 February 1943. These operations opened the Winter Campaign of 1942–1943 (19 November 1942 – 3 March 1943), which involved some 15 Armies operating on several fronts.

According to Zhukov, "German operational blunders were aggravated by poor intelligence: they failed to spot preparations for the major counter-offensive near Stalingrad where there were 10 field, 1 tank and 4 air armies."[18]

Weakness on the German flanks

During the siege, the German and allied Italian, Hungarian, and Romanian armies protecting Army Group B's flanks had pressed their headquarters for support. The Hungarian 2nd Army was given the task of defending a 200 km (120 mi) section of the front north of Stalingrad between the Italian Army and Voronezh. This resulted in a very thin line, with some sectors where 1–2 km (0.62–1.24 mi) stretches were being defended by a single platoon. These forces were also lacking in effective anti-tank weapons.

Zhukov states, "Compared with the Germans, the troops of the satellites were not so well armed, less experienced and less efficient, even in defence."[18]:95–96, 119, 122, 124

Because of the total focus on the city, the Axis forces had neglected for months to consolidate their positions along the natural defensive line of the Don River. The Soviet forces were allowed to retain bridgeheads on the right bank from which offensive operations could be quickly launched. These bridgeheads in retrospect presented a serious threat to Army Group B.[14]:915

Similarly, on the southern flank of the Stalingrad sector the front southwest of Kotelnikovo was held only by the Romanian 4th Army. Beyond that army, a single German division, the 16th Motorized Infantry, covered 400 km. Paulus had requested permission to "withdraw the 6th Army behind the Don," but was rejected. According to Paulus' comments to Adam, "There is still the order whereby no commander of an army group or an army has the right to relinquish a village, even a trench, without Hitler's consent."[22]:87–91, 95, 129

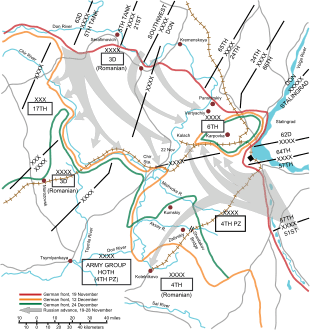

Operation Uranus: the Soviet offensive

In autumn, the Soviet generals Georgy Zhukov and Aleksandr Vasilevsky, responsible for strategic planning in the Stalingrad area, concentrated forces in the steppes to the north and south of the city. The northern flank was defended by Hungarian and Romanian units, often in open positions on the steppes. The natural line of defense, the Don River, had never been properly established by the German side. The armies in the area were also poorly equipped in terms of anti-tank weapons. The plan was to punch through the overstretched and weakly defended German flanks and surround the German forces in the Stalingrad region.

During the preparations for the attack, Marshal Zhukov personally visited the front and noticing the poor organization, insisted on a one-week delay in the start date of the planned attack.[30]:117 The operation was code-named "Uranus" and launched in conjunction with Operation Mars, which was directed at Army Group Center. The plan was similar to the one Zhukov had used to achieve victory at Khalkhin Gol three years before, where he had sprung a double envelopment and destroyed the 23rd Division of the Japanese army.[60]

On 19 November 1942, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus. The attacking Soviet units under the command of Gen. Nikolay Vatutin consisted of three complete armies, the 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank Army, and 21st Army, including a total of 18 infantry divisions, eight tank brigades, two motorized brigades, six cavalry divisions and one anti-tank brigade. The preparations for the attack could be heard by the Romanians, who continued to push for reinforcements, only to be refused again. Thinly spread, deployed in exposed positions, outnumbered and poorly equipped, the Romanian 3rd Army, which held the northern flank of the German 6th Army, was overrun.

Behind the front lines, no preparations had been made to defend key points in the rear such as Kalach. The response by the Wehrmacht was both chaotic and indecisive. Poor weather prevented effective air action against the Soviet offensive.

On 20 November, a second Soviet offensive (two armies) was launched to the south of Stalingrad against points held by the Romanian 4th Army Corps. The Romanian forces, made up primarily of infantry, were overrun by large numbers of tanks. The Soviet forces raced west and met on 23 November at the town of Kalach, sealing the ring around Stalingrad.[14]:926 The link-up of the Soviet forces, not filmed at the time, was later re-enacted for a propaganda film which was shown worldwide.

Sixth Army surrounded

About 265,000 German, Romanian, and Italian soldiers,[61] the 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment, and other volunteer subsidiary troops including some 40,000 Soviet conscripts and volunteers fighting for the Germans (Beevor states that one quarter of the sixth army's frontline strength were HIWIs, as collaborationists recruited from the ranks of Soviet POWs were called)[62] were surrounded. These Soviet HIWIs remained loyal, knowing the Soviet penalty for helping the Germans was summary execution. German strength in the pocket was about 210,000 according to strength breakdowns of the 20 field divisions (average size 9,000) and 100 battalion sized units of the Sixth Army on 19 November 1942. Inside the pocket (German: Kessel, literally "cauldron"), there were also around 10,000 Soviet civilians and several thousand Soviet soldiers the Germans had taken captive during the battle. Not all of the 6th Army was trapped; 50,000 soldiers were brushed aside outside the pocket. These belonged mostly to the other 2 divisions of the 6th Army between the Italian and Romanian Armies: the 62nd and 298th Infantry Divisions. Of the 210,000 Germans, 10,000 remained to fight on, 105,000 surrendered, 35,000 left by air and the remaining 60,000 died.

Army Group Don was formed under Field Marshal von Manstein. Under his command were the 20 German and 2 Romanian divisions encircled at Stalingrad, Adam's battle groups formed along the Chir River and on the Don bridgehead, plus the remains of the Romanian 3rd Army.[22]:107, 113

The Red Army units immediately formed two defensive fronts: a circumvallation facing inward and a contravallation facing outward. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein advised Hitler not to order the 6th Army to break out, stating that he could break through the Soviet lines and relieve the besieged 6th Army.[63] The American historians Williamson Murray and Alan Millet wrote that it was Manstein's message to Hitler on 24 November advising him that the 6th Army should not break out, along with Göring's statements that the Luftwaffe could supply Stalingrad that "... sealed the fate of the Sixth Army."[22]:133[64] After 1945, Manstein claimed that he told Hitler that the 6th Army must break out.[65] The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote that Manstein distorted his record on the matter.[66] Manstein was tasked to conduct a relief operation, named Operation Winter Storm (Unternehmen Wintergewitter) against Stalingrad, which he thought was feasible if the 6th Army was temporarily supplied through the air.[67][68]

Adolf Hitler had declared in a public speech (in the Berlin Sportpalast) on 30 September 1942 that the German army would never leave the city. At a meeting shortly after the Soviet encirclement, German army chiefs pushed for an immediate breakout to a new line on the west of the Don, but Hitler was at his Bavarian retreat of Obersalzberg in Berchtesgaden with the head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring. When asked by Hitler, Göring replied, after being convinced by Hans Jeschonnek,[5]:234 that the Luftwaffe could supply the 6th Army with an "air bridge." This would allow the Germans in the city to fight on temporarily while a relief force was assembled.[14]:926 A similar plan had been used a year earlier at the Demyansk Pocket, albeit on a much smaller scale: a corps at Demyansk rather than an entire army.[22]:132

The director of Luftflotte 4, Wolfram von Richthofen, tried to get this decision overturned. The forces under the 6th Army were almost twice as large as a regular German army unit, plus there was also a corps of the 4th Panzer Army trapped in the pocket. The maximum 107 t (118 short tons) they could deliver a day – based on the number of available aircraft and with only the airfield at Pitomnik to land at – was far less than the minimum 750 t (830 short tons) needed.[5][Note 6] To supplement the limited number of Junkers Ju 52 transports, the Germans pressed other aircraft into the role, such as the Heinkel He 177 bomber (some bombers performed adequately – the Heinkel He 111 proved to be quite capable and was much faster than the Ju 52). General Richthofen informed Manstein on 27 November of the small transport capacity of the Luftwaffe and the impossibility of supplying 300 tons a day by air. Manstein now saw the enormous technical difficulties of a supply by air of these dimensions. The next day he made a six-page situation report to the general staff. Based on the information of the expert Richthofen, he declared that contrary to the example of the pocket of Demyansk the permanent supply by air would be impossible. If only a narrow link could be established to Sixth Army, he proposed that this should be used to pull it out from the encirclement, and said that the Luftwaffe should instead of supplies deliver only enough ammunition and fuel for a breakout attempt. He acknowledged the heavy moral sacrifice the giving up of Stalingrad means but this is made easier to bear by the conservation of the combat power of Sixth Army and the regaining of the initiative ..."[69] He ignored the limited mobility of the army and the difficulties of disengaging the Soviets. Hitler reiterated that Sixth Army would stay at Stalingrad and that the air bridge would supply it until the encirclement was broken by a new German offensive.

Supplying the 270,000 men trapped in the "cauldron" required 700 tons of supplies a day. That would mean 350 Ju52 flights a day into Pitomnik. At a minimum, 500 tons were required. However, according to Adam, "On not one single day have the minimal essential number of tons of supplies been flown in."[22]:119, 127, 131, 134 The Luftwaffe was able to deliver an average of 85 t (94 short tons) of supplies per day out of an air transport capacity of 106 t (117 short tons) per day. The most successful day, 19 December, delivered 262 t (289 short tons) of supplies in 154 flights. The outcome of the airlift was the Luftwaffe's failure to provide its transport units with the tools they needed to maintain an adequate count of operational aircraft – tools that included airfield facilities, supplies, manpower, and even aircraft suited to the prevailing conditions. These factors, taken together, prevented the Luftwaffe from effectively employing the full potential of its transport forces, ensuring that they were unable to deliver the quantity of supplies needed to sustain the 6th Army.[70]

In the early parts of the operation, fuel was shipped at a higher priority than food and ammunition because of a belief that there would be a breakout from the city.[20]:153 Transport aircraft also evacuated technical specialists and sick or wounded personnel from the besieged enclave. Sources differ on the number flown out: at least 25,000 to at most 35,000. Carell: 42,000, of which 5000 did not survive.

Initially, supply flights came in from the field at Tatsinskaya,[22]:159 called 'Tazi' by the German pilots. On 23 December, the Soviet 24th Tank Corps, commanded by Major-General Vasily Mikhaylovich Badanov, reached nearby Skassirskaya and in the early morning of 24 December, the tanks reached Tatsinskaya. Without any soldiers to defend the airfield, it was abandoned under heavy fire; in a little under an hour, 108 Ju 52s and 16 Ju 86s took off for Novocherkassk – leaving 72 Ju 52s and many other aircraft burning on the ground. A new base was established some 300 km (190 mi) from Stalingrad at Salsk, the additional distance would become another obstacle to the resupply efforts. Salsk was abandoned in turn by mid-January for a rough facility at Zverevo, near Shakhty. The field at Zverevo was attacked repeatedly on 18 January and a further 50 Ju 52s were destroyed. Winter weather conditions, technical failures, heavy Soviet anti-aircraft fire and fighter interceptions eventually led to the loss of 488 German aircraft.

In spite of the failure of the German offensive to reach the 6th Army, the air supply operation continued under ever more difficult circumstances. The 6th Army slowly starved. General Zeitzler, moved by their plight, began to limit himself to their slim rations at meal times. After a few weeks on such a diet, he had "visibly lost weight", according to Albert Speer, and Hitler "commanded Zeitler to resume at once taking sufficient nourishment."[71]

The toll on the Transportgruppen was heavy. 160 aircraft were destroyed and 328 were heavily damaged (beyond repair). Some 266 Junkers Ju 52s were destroyed; one-third of the fleet's strength on the Eastern Front. The He 111 gruppen lost 165 aircraft in transport operations. Other losses included 42 Ju 86s, 9 Fw 200 Condors, 5 He 177 bombers and 1 Ju 290. The Luftwaffe also lost close to 1,000 highly experienced bomber crew personnel.[5]:310 So heavy were the Luftwaffe's losses that four of Luftflotte 4's transport units (KGrzbV 700, KGrzbV 900, I./KGrzbV 1 and II./KGzbV 1) were "formally dissolved."[2]:122

End of the battle

Operation Winter Storm

Soviet forces consolidated their positions around Stalingrad, and fierce fighting to shrink the pocket began. Operation Winter Storm (Operation Wintergewitter), the German attempt led by Erich von Manstein to relieve the trapped army from the south, was initially successful. By 18 December, the German Army had pushed to within 48 km (30 mi) of Sixth Army's positions. The starving encircled forces at Stalingrad made no attempt to break out or link up with Manstein's advance. Some German officers requested that Paulus defy Hitler's orders to stand fast and instead attempt to break out of the Stalingrad pocket. Paulus refused, concerned about the Red Army attacks on the flank of Army Group Don and Army Group B in their advance on Rostov-on-Don, "an early abandonment" of Stalingrad "would result in the destruction of Army Group A in the Caucasus," and the fact that his 6th Army tanks only had fuel for a 30 km advance towards Hoth's spearhead, a futile effort if they did not receive assurance of resupply by air. Of his questions to Army Group Don, Paulus was told, "Wait, implement Operation 'Thunderclap' only on explicit orders!" Operation Thunderclap being the code word initiating the breakout.[22]:132–33, 138–143, 150, 155, 165

On 23 December, the attempt to relieve Stalingrad was abandoned and Manstein's forces switched over to the defensive to deal with new Soviet offensives.[22]:153 As Zhukov states, "The military and political leadership of Nazi Germany sought not to relieve them, but to get them to fight on for as long possible so as to tie up the Soviet forces. The aim was to win as much time as possible to withdraw forces from the Caucasus and to rush troops from other Fronts to form a new front that would be able in some measure to check our counter-offensive."[18]:137

Operation Little Saturn

On 16 December, the Soviets launched Operation Little Saturn, which attempted to punch through the Axis army (mainly Italians) on the Don and take Rostov. The Germans set up a "mobile defense" of small units that were to hold towns until supporting armor arrived. From the Soviet bridgehead at Mamon, 15 divisions – supported by at least 100 tanks – attacked the Italian Cosseria and Ravenna Divisions, and although outnumbered 9 to 1, the Italians initially fought well, with the Germans praising the quality of the Italian defenders,[72] but on 19 December, with the Italian lines disintegrating, ARMIR headquarters ordered the battered divisions to withdraw to new lines.[73]

The fighting forced a total revaluation of the German situation. The attempt to break through to Stalingrad was abandoned and Army Group A was ordered to pull back from the Caucasus. The 6th Army now was beyond all hope of German relief. While a motorised breakout might have been possible in the first few weeks, the 6th Army now had insufficient fuel and the German soldiers would have faced great difficulty breaking through the Soviet lines on foot in harsh winter conditions. But in its defensive position on the Volga, 6th Army continued to tie down a significant number of Soviet Armies.[22]:159, 166–67

Soviet victory

The Red Army High Command sent three envoys while simultaneously aircraft and loudspeakers announced terms of capitulation on 7 Jan. 1943. The letter was signed by Colonel-General of Artillery Voronov and the commander-in-chief of the Don Front, Lieutenant-General Rokossovski. The German High Command informed Paulus, "Every day that the army holds out longer helps the whole front and draws away the Russian divisions from it."[22]:166, 168–69

The Germans inside the pocket retreated from the suburbs of Stalingrad to the city itself. The loss of the two airfields, at Pitomnik on 16 January 1943 and Gumrak on the night of 21/22 January,[74] meant an end to air supplies and to the evacuation of the wounded.[21]:98 The third and last serviceable runway was at the Stalingradskaya flight school, which reportedly had the last landings and takeoffs on 23 Jan.[34] After 23 Jan. there were no more reported landings, just intermittent air drops of ammunition and food until the end.[22]:183, 185, 189

The Germans were now not only starving, but running out of ammunition. Nevertheless, they continued to resist, in part because they believed the Soviets would execute any who surrendered. In particular, the so-called HiWis, Soviet citizens fighting for the Germans, had no illusions about their fate if captured. The Soviets were initially surprised by the number of Germans they had trapped, and had to reinforce their encircling troops. Bloody urban warfare began again in Stalingrad, but this time it was the Germans who were pushed back to the banks of the Volga. The Germans adopted a simple defense of fixing wire nets over all windows to protect themselves from grenades. The Soviets responded by fixing fish hooks to the grenades so they stuck to the nets when thrown.

The Germans had no usable tanks in the city, and those that still functioned could, at best, be used as makeshift pillboxes. The Soviets did not bother employing tanks in areas where the urban destruction restricted their mobility. A low-level Soviet envoy party (comprising Major Aleksandr Smyslov, Captain Nikolay Dyatlenko and a trumpeter) carried an offer to Paulus: if he surrendered within 24 hours, he would receive a guarantee of safety for all prisoners, medical care for the sick and wounded, prisoners being allowed to keep their personal belongings, "normal" food rations, and repatriation to any country they wished after the war; but Paulus – ordered not to surrender by Hitler – did not respond.[75]:283

On 22 January, Paulus requested that he be granted permission to surrender. Hitler rejected it on a point of honour. He telegraphed the 6th Army later that day, claiming that it had made a historic contribution to the greatest struggle in German history and that it should stand fast "to the last soldier and the last bullet." Hitler told Goebbels that the plight of the 6th Army was a "heroic drama of German history."[76]

On 24 Jan., in his radio report to Hitler, Paulus reported "18,000 wounded without the slightest aid of bandages and medicines."[22]:193

On 26 January 1943, the German forces inside Stalingrad were split into two pockets north and south of Mamai-Kurgan. The northern pocket consisting of the VIIIth Corps, under General Walter Heitz, and the XIth Corps, was now cut off from telephone communication with Paulus in the southern pocket. Now "each part of the cauldron came personally under Hitler."[22]:201, 203

On 28 Jan., the cauldron was split into three parts. The northern cauldron consisted of the XIth Corps, the central with the VIIIth and LIst Corps, and the southern with the XIVth Panzer Corps and IVth Corps "without units". The sick and wounded reached 40,000 to 50,000.[22]:203

On 30 January 1943, the 10th anniversary of Hitler's coming to power, Goebbels read out a proclamation that included the sentence: "The heroic struggle of our soldiers on the Volga should be a warning for everybody to do the utmost for the struggle for Germany's freedom and the future of our people, and thus in a wider sense for the maintenance of our entire continent."[77] Hitler promoted Paulus to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall. No German field marshal had ever surrendered, and the implication was clear: if Paulus surrendered, he would shame himself and would become the highest ranking German officer ever to be captured. Hitler believed that Paulus would either fight to the last man or commit suicide.[22]:212[78]

On the next day, the southern pocket in Stalingrad collapsed. Soviet forces reached the entrance to the German headquarters in the ruined GUM department store. General Schmidt negotiated a surrender of the headquarters while Paulus was unaware in another room.[22]:207–08, 212–15 When interrogated by the Soviets, Paulus claimed that he had not surrendered. He said that he had been taken by surprise. He denied that he was the commander of the remaining northern pocket in Stalingrad and refused to issue an order in his name for them to surrender.[79][80] The central pocket, under the command of Heitz, surrendered the same day while the northern pocket, under the command of Strecker, held out for two more days.[22]:215

Four Soviet armies were deployed against the remaining northern pocket. At four in the morning on 2 February, General Strecker was informed that one of his own officers had gone to the Soviets to negotiate surrender terms. Seeing no point in continuing, he sent a radio message saying that his command had done its duty and fought to the last man. He then surrendered. Around 91,000 exhausted, ill, wounded, and starving prisoners were taken, including 3,000 Romanians (the survivors of the 20th Infantry Division, 1st Cavalry Division and "Col. Voicu" Detachment).[81] The prisoners included 22 generals. Hitler was furious and confided that Paulus "could have freed himself from all sorrow and ascended into eternity and national immortality, but he prefers to go to Moscow."[82]

Aftermath

The German public was not officially told of the impending disaster until the end of January 1943, though positive media reports had stopped in the weeks before the announcement.[83] Stalingrad marked the first time that the Nazi government publicly acknowledged a failure in its war effort; it was not only the first big defeat for the German military but German losses were almost equal to those of the Soviets and this was unprecedented. Previous Soviet losses were generally three times as high as those of the Germans.[83] On 31 January, regular programmes on German state radio were replaced by a broadcast of the somber Adagio movement from Anton Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, followed by the announcement of the defeat at Stalingrad.[83] On 18 February, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gave the famous Sportpalast speech in Berlin, encouraging the Germans to accept a total war that would claim all resources and efforts from the entire population.

Based on Soviet records, over 10,000 soldiers continued to resist in isolated groups within the city for the next month. Some have presumed that they were motivated by a belief that fighting on was better than a slow death in Soviet captivity. Brown University historian Omer Bartov claims they were motivated by National Socialism. He studied 11,237 letters sent by soldiers inside of Stalingrad between 20 December 1942 and 16 January 1943 to their families in Germany. Almost every letter expressed belief in Germany's ultimate victory and their willingness to fight and die at Stalingrad to achieve that victory.[84] Bartov reported that a great many of the soldiers were well aware that they would not be able to escape from Stalingrad but in their letters to their families boasted that they were proud to "sacrifice themselves for the Führer".[84]

The remaining forces continued to resist, hiding in cellars and sewers but by early March 1943, the last small and isolated pockets of resistance had surrendered. According to Soviet intelligence documents shown in the documentary, a remarkable NKVD report from March 1943 is available showing the tenacity of some of these German groups:

The mopping-up of counter-revolutionary elements in the city of Stalingrad proceeded. The German soldiers – who had hidden themselves in huts and trenches – offered armed resistance after combat actions had already ended. This armed resistance continued until 15 February and in a few areas until 20 February. Most of the armed groups were liquidated by March ... During this period of armed conflict with the Germans, the brigade's units killed 2,418 soldiers and officers and captured 8,646 soldiers and officers, escorting them to POW camps and handing them over.

The operative report of the Don Front's staff issued on 5 February 1943, 22:00 said,

The 64th Army was putting itself in order, being in previously occupied regions. Location of army's units is as it was previously. In the region of location of the 38 Motorized Rifle Brigade in a basement 18 armed SS-men (sic) were found, who refused to surrender, the Germans found were destroyed.[85]

The condition of the troops that surrendered was pitiful. British war correspondent Alexander Werth described the following scene in his Russia at War book, based on a first-hand account of his visit to Stalingrad from 3–5 February 1943,

We [...] went into the yard of the large burnt out building of the Red Army House; and here one realized particularly clearly what the last days of Stalingrad had been to so many of the Germans. In the porch lay the skeleton of a horse, with only a few scraps of meat still clinging to its ribs. Then we came into the yard. Here lay more more horses' skeletons, and to the right, there was an enormous horrible cesspool – fortunately, frozen solid. And then, suddenly, at the far end of the yard I caught sight of a human figure. He had been crouching over another cesspool, and now, noticing us, he was hastily pulling up his pants, and then he slunk away into the door of the basement. But as he passed, I caught a glimpse of the wretch's face – with its mixture of suffering and idiot-like incomprehension. For a moment, I wished that the whole of Germany were there to see it. The man was probably already dying. In that basement [...] there were still two hundred Germans—dying of hunger and frostbite. "We haven't had time to deal with them yet," one of the Russians said. "They'll be taken away tomorrow, I suppose." And, at the far end of the yard, besides the other cesspool, behind a low stone wall, the yellow corpses of skinny Germans were piled up – men who had died in that basement—about a dozen wax-like dummies. We did not go into the basement itself – what was the use? There was nothing we could do for them.[86]

Out of the nearly 91,000 German prisoners captured in Stalingrad, only about 5,000 returned.[87] Weakened by disease, starvation and lack of medical care during the encirclement, they were sent on foot marches to prisoner camps and later to labour camps all over the Soviet Union. Some 35,000 were eventually sent on transports, of which 17,000 did not survive. Most died of wounds, disease (particularly typhus), cold, overwork, mistreatment and malnutrition. Some were kept in the city to help rebuild.

A handful of senior officers were taken to Moscow and used for propaganda purposes, and some of them joined the National Committee for a Free Germany. Some, including Paulus, signed anti-Hitler statements that were broadcast to German troops. Paulus testified for the prosecution during the Nuremberg Trials and assured families in Germany that those soldiers taken prisoner at Stalingrad were safe.[29]:401 He remained in the Soviet Union until 1952, then moved to Dresden in East Germany, where he spent the remainder of his days defending his actions at Stalingrad and was quoted as saying that Communism was the best hope for postwar Europe.[29]:280 General Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach offered to raise an anti-Hitler army from the Stalingrad survivors, but the Soviets did not accept. It was not until 1955 that the last of the 5,000–6,000 survivors were repatriated (to West Germany) after a plea to the Politburo by Konrad Adenauer.

Significance

Stalingrad has been described as the biggest defeat in the history of the German Army.[88] It is often identified as the turning point on the Eastern Front, in the war against Germany overall, and the entire Second World War.[18]:142[89] Before Stalingrad, the German forces had gone from victory to victory on the Eastern Front, with a limited setback in the winter of 1941–42. After Stalingrad, they won no decisive battles, even in summer.[90] The Red Army had the initiative, and the Wehrmacht was in retreat. A year of German gains during Case Blue had been wiped out. Germany's Sixth Army had ceased to exist, and the forces of Germany's European allies, except Finland, had been shattered.[91] In a speech on 9 November 1944, Hitler himself blamed Stalingrad for Germany's impending doom.[92]

Stalingrad's significance has been downplayed by some historians, who point either to the Battle of Moscow or the Battle of Kursk as more strategically decisive. Others maintain that the destruction of an entire army (the largest killed, captured, wounded figures for Axis soldiers, nearly 1 million, during the war) and the frustration of Germany's grand strategy made the battle a watershed moment.[93] At the time, however, the global significance of the battle was not in doubt. Writing in his diary on 1 January 1943, British General Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, reflected on the change in the position from a year before:

I felt Russia could never hold, Caucasus was bound to be penetrated, and Abadan (our Achilles heel) would be captured with the consequent collapse of Middle East, India, etc. After Russia's defeat how were we to handle the German land and air forces liberated? England would be again bombarded, threat of invasion revived... And now! We start 1943 under conditions I would never have dared to hope. Russia has held, Egypt for the present is safe. There is a hope of clearing North Africa of Germans in the near future... Russia is scoring wonderful successes in Southern Russia.[93]

At this point, the British had won the Battle of El Alamein in November 1942. However, there were only about 50,000 German soldiers at El Alamein in Egypt, while at Stalingrad 200,000 Germans had been lost.[93]

Regardless of the strategic implications, there is little doubt about Stalingrad's symbolism. Germany's defeat shattered its reputation for invincibility and dealt a devastating blow to German morale. On 30 January 1943, the tenth anniversary of his coming to power, Hitler chose not to speak. Joseph Goebbels read the text of his speech for him on the radio. The speech contained an oblique reference to the battle, which suggested that Germany was now in a defensive war. The public mood was sullen, depressed, fearful, and war-weary. Germany was looking in the face of defeat.[94]

The reverse was the case on the Soviet side. There was an overwhelming surge in confidence and belief in victory. A common saying was: "You cannot stop an army which has done Stalingrad." Stalin was feted as the hero of the hour and made a Marshal of the Soviet Union.[95] In recognition of the determination of its defenders, Stalingrad was awarded the title Hero City in 1945. A colossal monument called The Motherland Calls was erected in 1967 on Mamayev Kurgan, the hill overlooking the city where bones and rusty metal splinters can still be found.[96] The statue forms part of a war memorial complex which includes the ruins of the Grain Silo and Pavlov's House.

The news of the battle echoed round the world, with many people now believing that Hitler's defeat was inevitable.[97] The Turkish Consul in Moscow predicted that "the lands which the Germans have destined for their living space will become their dying space".[98] Britain's conservative The Daily Telegraph proclaimed that the victory had saved European civilisation.[98] The country celebrated "Red Army Day" on 23 February 1943. A ceremonial Sword of Stalingrad was forged by King George VI. After being put on public display in Britain, this was presented to Stalin by Winston Churchill at the Tehran Conference later in 1943.[95] Soviet propaganda spared no effort and wasted no time in capitalising on the triumph, impressing a global audience. The prestige of Stalin, the Soviet Union, and the worldwide Communist movement was immense, and their political position greatly enhanced.[99]

On 3 February 2013 Russian President Vladimir Putin flew to the city to join a military parade commemorating the 70th anniversary of the final victory.[100]

More information

Orders of battle

Red Army

During the defence of Stalingrad, the Red Army deployed five armies (28th, 51st, 57th, 62nd and 64th Armies) in and around the city and an additional nine armies in the encirclement counter offensive.[30]:435–438 The nine armies amassed for the counteroffensive were the 24th Army, 65th Army, 66th Army and 16th Air Army from the north as part of the Don Front offensive and 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank, 21st Army, 2nd Air Army and 17th Air Army from the south as part of the Southwestern Front.

Axis

Casualties

The calculation of casualties depends on what scope is given to the Battle of Stalingrad. The scope can vary from the fighting in the city and suburbs to the inclusion of almost all fighting on the southern wing of the Soviet–German front from the spring of 1942 to the end of the fighting in the city in the winter of 1943. Scholars have produced different estimates depending on their definition of the scope of the battle. The difference is comparing the city against the region. The Axis suffered 730,000 total casualties (wounded, killed, captured) among all branches of the German armed forces and its allies; 400,000 Germans,[101] 109,000 Romanians of which at least 70,000 were captured or missing, 114,000 Italians and 105,000 Hungarians were killed, wounded or captured.[102]

The Germans lost 900 aircraft (including 274 transports and 165 bombers used as transports), 500 tanks and 6,000 artillery pieces.[2]:122–23 According to a contemporary Soviet report, 5,762 guns, 1,312 mortars, 12,701 heavy machine guns, 156,987 rifles, 80,438 sub-machine guns, 10,722 trucks, 744 aircraft; 1,666 tanks, 261 other armored vehicles, 571 half-tracks and 10,679 motorcycles were captured by the Soviets.[103] An unknown amount of Hungarian, Italian, and Romanian materiel was lost.

The USSR, according to archival figures, suffered 1,129,619 total casualties; 478,741 personnel killed or missing, and 650,878 wounded or sick. The USSR lost 4,341 tanks destroyed or damaged, 15,728 artillery pieces and 2,769 combat aircraft.[104][105] 955 Soviet civilians died in Stalingrad and its suburbs from aerial bombing by Luftflotte 4 as the German 4th Panzer and 6th Armies approached the city.[2]:73

Luftwaffe losses

| Losses | Aircraft type |

|---|---|

| 269 | Junkers Ju 52 |

| 169 | Heinkel He 111 |

| 42 | Junkers Ju 86 |

| 9 | Focke-Wulf Fw 200 |

| 5 | Heinkel He 177 |

| 1 | Junkers Ju 290 |

| Total: 495 | About 20 squadrons or more than an air corps |

The losses of transport planes were especially serious, as they destroyed the capacity for supply of the trapped 6th Army. The destruction of 72 aircraft when the airfield at Tatsinskaya was overrun meant the loss of about 10 percent of the Luftwaffe transport fleet.[106]

These losses amounted to about 50 percent of the aircraft committed and the Luftwaffe training program was stopped and sorties in other theaters of war were significantly reduced to save fuel for use at Stalingrad.

In popular culture

The events of the Battle for Stalingrad have been covered in numerous media works of British, American, German, and Russian[107] origin, for its significance as a turning point in the Second World War and for the loss of life associated with the battle. The term Stalingrad has become almost synonymous with large-scale urban battles with high casualties on both sides.

See also

- Barmaley Fountain

- Hitler Stalingrad Speech

- Italian participation in the Eastern Front

- List of officers and commanders in the Battle of Stalingrad

References

Footnotes

- ↑ The Soviet front's composition and names changed several times in the battle. The battle started with the South Western Front. It was later renamed Stalingrad Front, then had the Don Front split off from it.

- ↑ The Front was reformed from reserve armies on 22 October 1942.

- ↑ This force grew to 1,600 in early September by withdrawing forces from the Kuban region and South Caucasus: Hayward (1998), p. 195.

- ↑ Bergström quotes: Soviet Reports on the effects of air raids between 23–26 August 1942. This indicates 955 people were killed and another 1,181 wounded

- ↑ 8,314 German aircraft were produced from July–December 1942, but this could not keep pace with a three-front aerial war of attrition

- ↑ Shirer p. 926 says that "Paulus radioed that they would need a minimum of 750 tons of supplies day flown in," while Craig pp. 206–07 quotes Zeitzler as pressing Goering about his boast that the Luftwaffe could airlift the needed supplies: "Are you aware ... how many daily sorties the army in Stalingrad will need? ... Seven hundred tons! Every day!"

Citations

- 1 2 3 Bellamy 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Bergström 2007

- ↑ Glantz 1995, p. 346

- ↑ Anthony Tihamér Komjáthy (1982). A Thousand Years of the Hungarian Art of War. Toronto: Rakoczi Foundation. pp. 144–45. ISBN 978-0-8191-6524-4. OCLC 26807671.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hayward 1998

- ↑ Bergström 2006.

- 1 2 Glantz 1995, p. 134

- ↑ McDougal Littell, (2006)

- ↑ Roberts (2006: 143)

- ↑ Biesinger (2006: 699): "On August 23, 1942, the Germans began their attack."

- ↑ "Battle of Stalingrad". Encyclopædia Britannica.

By the end of August, ... Gen. Friedrich Paulus, with 330,000 of the German Army's finest troops ... approached Stalingrad. On 23 August a German spearhead penetrated the city's northern suburbs, and the Luftwaffe rained incendiary bombs that destroyed most of the city's wooden housing.

- ↑ Luhn, Alec (8 June 2014). "Stalingrad name may return to city in wave of second world war patriotism". theguardian.com. The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Beevor (1998: 239)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shirer 1990

- 1 2 3 Kershaw 2000

- ↑ Taylor and Clark, (1974)

- ↑ P.M.H. Bell, Twelve Turning Points of the Second World War, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011, p. 96

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zhukov, Georgy (1974). Marshal of Victory, Volume II. Pen and Sword Books Ltd. pp. 110–11. ISBN 9781781592915.

- ↑ Michael Burleigh (2001). The Third Reich: A New History. Pan. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-330-48757-3.

- 1 2 Walsh, Stephen. (2000). Stalingrad 1942–1943 The Infernal Cauldron. London, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0916-8.

- 1 2 MacDonald 1986

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Adam, Wilhelm; Ruhle, Otto (2015). With Paulus at Stalingrad. Translated by Tony Le Tissier. Pen and Sword Books Ltd. pp. 18, 22. ISBN 9781473833869.

- ↑ German High Command (communique) (27 October 1941). "Text of the Day's War Communiques". New York Times (28 October 1941). Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ↑ German High Command (communique) (10 November 1942). "Text of the Day's War Communiques on Fighting in Various Zones". New York Times (10 November 1942). Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ↑ German High Command (communique) (26 August 1942). "Text of the Day's War Communiques on Fighting in Various Zones". New York Times (26 August 1942). Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ↑ German High Command (communique) (12 December 1942). "Text of the Day's War Communiques". New York Times (12 December 1942). Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ↑ "In spite of the unfavourable balance of forces – the 'Cosseria' and the 'Ravenna' faced eight to nine Russian divisions and an unknown number of tanks – the atmosphere among Italian staffs and troops was certainly not pessimistic.... The Italians, especially the officers of the 'Cosseria', had confidence in what they thought were well built defensive positions." All or Nothing: The Axis and the Holocaust 1941–43, Jonathan Steinberg, p. ?, Routledge, 2003

- ↑ "The attack at dawn failed to penetrate fully at first and developed into a grim struggle with Italian strongpoints, lasting for hours. The Ravenna Division was the first to be overrun. A gap emerged that was hard to close, and there was no holding back the Red Army when it deployed the mass of its tank forces the following day. German reinforcements came too late in the breakthrough battle." The Unknown Eastern Front: The Wehrmacht and Hitler's Foreign Soldiers, Rolf-Dieter Müller, p. 84, I.B.Tauris, 28 Feb 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 Craig 1973

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Beevor 1998, pp. 198

- ↑ "Battle of Stalingrad". WWII in HD. Secrets of The Dead: Deadliest Battle. 38 minutes in.

- 1 2 Clark, Lloyd, Kursk: The Greatest Battle: Eastern Front 1943, 2011, p. 157

- ↑ Bergström, Christer, (2007)

- 1 2 Pojić, Milan. Hrvatska pukovnija 369. na Istočnom bojištu 1941–1943.. Croatian State Archives. Zagreb, 2007.

- ↑ Clark, Lloyd, Kursk: The greatest battle: Eastern Front 1943, 2011, pp. 164–65

- ↑ "Stalingrad 1942". Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 84–85, 97, 144

- ↑ Krivosheev, G. I. (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. Greenhill Books. pp. 51–97. ISBN 978-1-85367-280-4.

- 1 2 3 TV Novosti. "Crucial WW2 battle remembered". Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ↑ Bellamy 2007, pp. 514–17

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 135–37

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 203–06

- ↑ Beevor 2004

- ↑ Overy, Richard. Russia's War (New York: 1997), 201.

- ↑ Merridale, Catherine. Ivan's War (New York: 2006), 156.

- ↑ quoted in Merridale, Catherine. Ivan's War (New York: 2006), 156.

- ↑ Bellamy 2007, pp. 520–21

- ↑ Pennington 2004, pp. 180–82

- ↑ Pennington 2004, p. 178

- ↑ Pennington 2004, pp. 189–92

- ↑ Pennington 2004, pp. 192–94

- 1 2 Pennington 2004, p. 197

- ↑ Pennington 2004, pp. 201–04

- ↑ Pennington 2004, pp. 204–07

- ↑ Alexander Werth, The Year of Stalingrad (London: 1946), 193–94.

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 141–42

- ↑ Golovanov 2004

- ↑ Goodwin 1994

- ↑ Bellamy 2007, p. 516

- ↑ Maps of the conflict. Leavenworth Papers No. 2 Nomonhan: Japanese-Soviet Tactical Combat, 1939; MAPS Archived 1 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ↑ Manstein 2004

- ↑ Beevor, Antony (1999). Stalingrad. London: Penguin. p. 184. ISBN 0-14-024985-0. Beevor states that one quarter of the sixth army's frontline strength were HIWIs. Note: this reference still does not directly support the claim that there were 40,000 HIWIs

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 p. 451

- ↑ Murray, Williamson & Millet, Alan War To Be Won, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 p. 288.

- ↑ Weinberg A World In Arms, 2005 451.

- ↑ Weinberg, 2005 A World In Arms, p. 1045.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 408, 449, 451.

- ↑ Manstein 2004, pp. 315; 334.

- ↑ Kehrig, Manfred Stalingrad, Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags Anstalt, 1974 pp. 279, 311–12, 575.

- ↑ Bates, Aaron (April 2016). "For Want of the Means: A Logistical Appraisal of the Stalingrad Airlift". The Journal of Slavic military studies. 29: 298–318. doi:10.1080/13518046.2016.1168137.

- ↑ Speer, Albert (1995). Inside the Third Reich. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 343–347. ISBN 9781842127353.

- ↑ "During this phase, the Germans praised the steadfastness of Italian infantry, who held out tenaciously even in isolated strongpoints, but eventually reached their breaking-point under this constant pressure. " The Unknown Eastern Front: The Wehrmacht and Hitler's Foreign Soldiers, Rolf-Dieter Müller, p. 83–84, I.B.Tauris, 28 Feb 2014

- ↑ Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International. p. 177. ISBN 0-275-98505-9. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Deiml, Michael (1999). Meine Stalingradeinsätze (My Stalingrad Sorties) Archived 3 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.. Einsätze des Bordmechanikers Gefr. Michael Deiml (Sorties of Aviation Mechanic Private Michael Deiml). Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Clark 1995

- ↑ Kershaw 2000, p. 549

- ↑ Kershaw 2000, p. 550

- ↑ Bellamy 2007, p. 549

- ↑ Beevor, p. 390

- ↑ Bellamy 2007, p. 550

- ↑ Pusca, Dragos; Nitu, Victor. The Battle of Stalingrad – 1942 Romanian Armed Forces in the Second World War (worldwar2.ro). Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Victor, George (2000). Hitler: Pathology of Evil. Washington, DC: Brassey's Inc. p. 208. ISBN 1-57488-228-7. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- 1 2 3 Sandlin, Lee (1997). "Losing the War". Originally published in Chicago Reader, 7 and 14 March 1997. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- 1 2 Bartov, Omer Hitler's Army Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991 pp. 166–67

- ↑ Google Video: Stalingrad – OSA III – Stalingradin taistelu päättyy (Stalingrad, Part 3: Battle of Stalingrad ends) (Television documentary. German original: "Stalingrad" Episode 3: "Der Untergang, 53 min, Sebastian Dehnhardt, Manfred Oldenburg (directors) IMDB) (in Finnish, German, and Russian). broadview.tv GmbH, Germany 2003. Archived from the original (Adobe Flash) on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ↑ Alexander Werth, Russia at War 1941–1945, New York, E. P. Dutton & Co, Inc., 1964, p. 562

- ↑ How three million Germans died after VE Day. Nigel Jones reviews After the Reich: From the Liberation of Vienna to the Berlin Airlift by Giles MacDonogh. The Telegraph, 18 Apr 2007.

- ↑ P.M.H. Bell, Twelve Turning Points of the Second World War, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011, p 104

- ↑ Gordon Corrigan, The Second World War: a Military History, Atlantic, London, p 353.