Decembrist revolt

| Decembrist Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Decembrists at Peter's Square | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 3,000 soldiers of the Imperial Russian Army | Imperial Russian Army | ||||||

The Decembrist revolt or the Decembrist uprising (Russian: Восстание декабристов, transliteration: Vosstanie dekabristov) took place in Imperial Russia on 26 December [O.S. 14 December] 1825. Russian army officers led about 3,000 soldiers in a protest against Tsar Nicholas I's assumption of the throne after his elder brother Constantine removed himself from the line of succession. Because these events occurred in December, the rebels were called the Decembrists (Dekabristy, Russian: Декабристы). This uprising, which was suppressed by Nicholas I, took place in Peter's Square in Saint Petersburg. In 1925, to mark the centenary of the event, the square was renamed as Decembrist Square, but in 2008 the name was changed to Senate Square.

Union of Salvation

In 1816, several officers of the Imperial Russian Guard founded a society known as the Union of Salvation, or of the Faithful and True Sons of the Fatherland. The society acquired a more liberal cast after it was joined by the idealistic Pavel Pestel. After a mutiny in the Semenovsky Regiment in 1820, the society decided to suspend activity in 1821. Two groups, however, continued to function secretly: a Southern Society, based at Tulchin, a small garrison town in Ukraine, in which Pestel was the outstanding figure, and a Northern Society, based at St Petersburg, led by Guard officers Nikita Muraviev, Prince S. P. Trubetskoy and Prince Eugene Obolensky.[1] The political aims of the more moderate Northern Society were a British-style constitutional monarchy with a limited franchise, the abolition of serfdom, and equality before the law. The Southern Society, under Pestel's influence, was more radical and wanted to abolish the monarchy, establish a republic and redistribute land: taking half into state ownership and dividing the rest among the peasants.[1]

At first, many officers were encouraged by Tsar Alexander I's early liberal reformation of Russian society and politics. In 1819 Count Mikhail Mikhailovich Speransky was appointed as the Governor of Siberia, with the task of reforming local government. Equally, in 1818 the Tsar asked Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev to draw up a constitution.[2] However, internal and external unrest, which the Tsar believed stemmed from political liberalisation, led to a series of repressions and a return to a former government of restriction and conservatism.

Meanwhile, spurred by their experiences of the Napoleonic Wars, and realising many of the harsh indignities through which the peasant soldiers were forced,[3] Decembrist officers and sympathisers displayed their contempt for the ancien régime by rejecting court lifestyle, wearing their cavalry swords at balls (indicating their unwillingness to dance), and committing themselves to academic study. This new lifestyle captured the spirit of the times, as a willingness to embrace both the peasant (i.e., the 'Russian way of life') and ongoing reformative movements abroad.

The motivations for the reformist movement are outlined, in part, by Pavel Pestel:

The desirability of granting freedom to the serfs was considered from the very beginning; for that purpose a majority of the nobility was to be invited in order to petition the Emperor about it. This was later thought of on many occasions, but we soon came to realize that the nobility could not be persuaded. And as time went on we became even more convinced, when the Ukrainian nobility absolutely rejected a similar project of their military governor.[4]

Historians have also noted that the United States Declaration of Independence may have influenced the revolutionaries.

At Senate Square

When Tsar Alexander I died on 1 December [O.S. 19 November] 1825, the royal guards swore allegiance to the presumed heir, Alexander's brother Constantine. When Constantine made his renunciation public, and Nicholas stepped forward to assume the throne, the Northern Society acted. With the capital in temporary confusion, and one oath to Constantine having already been sworn, the society scrambled in secret meetings to convince regimental leaders not to swear allegiance to Nicholas. These efforts would culminate in the Decembrist Revolt. The leaders of the society (many of whom belonged to the high aristocracy) elected Prince Sergei Trubetskoy as interim dictator.

On the morning of 26 December [O.S. 14 December], a group of officers commanding about 3,000 men assembled in Senate Square, where they refused to swear allegiance to the new tsar, Nicholas I, proclaiming instead their loyalty to Constantine and their Decembrist Constitution. They expected to be joined by the rest of the troops stationed in Saint Petersburg, but they were disappointed. The revolt was further hampered when it was deserted by its supposed leader Prince Trubetskoy, who had a last-minute change of heart, and failed to turn up at the Square. His second-in-command, Colonel Bulatov, also vanished from the scene. After a hurried consultation, the rebels appointed Prince Eugene Obolensky as a replacement leader.[5]

For hours there was a stand-off between the 3,000 rebels and the 9,000 loyal troops stationed outside the Senate building, with some desultory shooting from the rebel side. A vast crowd of civilian on-lookers began fraternizing with the rebels, but did not join the action.[6] Eventually Nicholas, the new Tsar, appeared in person, at the square, and sent Count Mikhail Miloradovich, a military hero who was greatly respected by ordinary soldiers, to parley with the rebels. Miloradovich was fatally shot by Pyotr Kakhovsky while delivering a public address to defuse the situation. At the same time, a rebelling squad of grenadiers, led by Lieutenant Nikolay Panov, entered the Winter Palace but failed to seize it, and retreated.

After spending most of the day in fruitless attempts to parley with the rebel force, Nicholas ordered a cavalry charge which slipped on the icy cobbles and retired in disorder. Eventually, at the end of the day, Nicholas ordered three artillery pieces to open fire, with devastating effect. To avoid the slaughter the rebels broke and ran. Some attempted to regroup on the frozen surface of the river Neva, to the north. However, here too they were targeted by the artillery and suffered many casualties. As the ice was broken by the cannon fire, many of the dead and dying were cast into the river. After a nighttime mopping-up operation by loyal army and police units, the revolt in the north came to an end.[7]

Arrests and trial

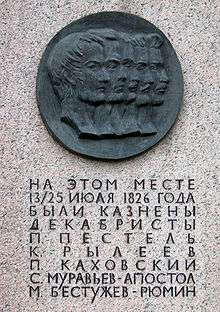

The text reads: На этом месте, 13/25 Июля 1826, года были казнены Декабристы П. Пестель, К. Рылеев, П. Каховский, С. Муравьев-Апостол, М. бестужев-Рюмин.

(English: "At this place, 13/25 July 1826, were executed the Decembrists P. Pestel, K. Ryleyev, P. Kakhovsky, S. Muravyov-Apostol and M. Bestuzhev-Ryumin")

While the Northern Society scrambled in the days leading up to the revolt, the Southern Society (based in Tulchin) took a serious blow. The day before (25 December [O.S. 13 December]), acting on reports of treason, the police arrested Pavel Pestel. It took two weeks for the Southern Society to learn of the events in the capital. Meanwhile, other members of the leadership were arrested. The Southern Society, and a nationalistic group called the United Slavs discussed revolt. When learning of the location of some of the arrested men, the United Slavs freed them by force. One of the freed men, Sergey Muravyov-Apostol, assumed leadership of the revolt. After converting the soldiers of Vasilkov to the cause, Muraviev-Apostol easily captured the city. The rebelling army was soon confronted by superior forces armed with artillery loaded with grapeshot, and with orders to destroy the rebels.

On 15 January [O.S. 3 January] 1826, the rebels met defeat and the surviving leaders were sent to Saint Petersburg to stand trial with the northern leaders. The Decembrists were taken to the Winter Palace to be interrogated, tried, and convicted. The shooter Kakhovsky was executed by hanging, together with four other leading Decembrists: Pavel Pestel; the poet Kondraty Ryleyev; Sergey Muravyov-Apostol; and Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Other Decembrists were exiled to Siberia, Kazakhstan, and the Far East.

Suspicion also fell on several eminent persons who were on friendly terms with the Decembrist leaders and could have been aware of their clandestine organizations, notably Alexander Pushkin, Aleksander Griboyedov, and Aleksey Yermolov.

Decembrists in Siberia

On 25 July [O.S. 13 July] 1826, the first party of Decembrist convicts began its exodus to Siberia. Among this group, were Prince Trubetskoi, Prince Obolensky, Peter and Andrei Borisov, Prince Volkonsky, and Artamon Muraviev, all of them bound for the mines at Nerchinsk.[8][9] The journey eastward was fraught with hardship, yet for many, it offered refreshing changes in scenery and peoples, following imprisonment. Decembrist Nikolay Vasil’yevich Basargin was unwell when he set out from St. Petersburg, but he recovered his strength on the move; his memoirs depict the journey to Siberia in a cheerful light, full of praise for the “common people” and commanding landscapes.[10]

Not all Decembrists could identify with Basargin’s positive experience. Because of their lower social standing, “soldier-Decembrists” experienced the Emperor’s vengeance in full. Sentenced by court-martial, many of these “commoners” received thousands of lashes. Those that survived journeyed to Siberia on foot, chained alongside common criminals.[11]

Fifteen out of 124 Decembrists were convicted of “state-crimes” by the Supreme Criminal Court, and sentenced to “exile-to-settlement.” [12] These men were sent directly to isolated locales, such as Berezov, Narym, Surgut, Pelym, Irkutsk, Yakutsk, and Viliuisk, among others. Few Russians inhabited these places: the populations consisted mainly of Siberian aborigines, Tunguses, Yakuts, Tartars, Ostiaks, Mongols, and Buriats.[13]

Of all those exiled, the largest group of prisoners was sent to Chita, Zabaykalsky Krai, to be transferred three years later to Petrovsky Zavod, near Nerchinsk.[14] This group, sentenced to hard labor, included principal leaders of the Decembrist movement, as well as Polish revolutionaries. Siberian Governor-General Lavinsky argued that it would be easiest to control a large, concentrated group of convicts,[13] and Emperor Nicholas I pursued this policy in order to maximize surveillance and to limit revolutionaries’ contact with local populations.[15] Concentration facilitated the guarding of prisoners, but it also allowed the Decembrists to continue to exist as a community.[13] This was especially true at Chita. The move to Petrovsky Zavod, however, forced Decembrists to divide into smaller groups; the new location was compartmentalized, with an oppressive sense of order. Convicts could no longer congregate casually. Although nothing could destroy the Decembrists’ conception of fraternity, Petrovsky Zavod forced them to live more private lives.[16] Owing to a number of imperial sentence reductions, exiles started to complete their labor terms years ahead of schedule. The labor itself was of minimal travail; Stanislav Leparsky, commandant of Petrovsky Zavod, failed to enforce Decembrists’ original labor sentences, and criminal convicts carried out much of the work in place of the revolutionaries. Most Decembrists left Petrovsky Zavod between 1835 and 1837, settling in or near Irkutsk, Minusinsk, Kurgan, Tobol’sk, Turinsk, and Yalutorovsk.[15] Those Decembrists who had already lived in or visited Siberia, such as Dimitri Zavalishin, prospered upon leaving Petrovsky Zavod’s confines, but most found it physically arduous and more psychologically unnerving than prison life.[17]

The Siberian population met the Decembrists with great hospitality. Natives played central roles in keeping lines of communication open among Decembrists, friends, and relatives. Most merchants and state employees were also sympathetic. To the masses, the Decembrist exiles were “generals who had refused to take the oath to Nicholas I.” They were great figures that had suffered political persecution for their loyalty to the people. On the whole, indigenous Siberian populations greatly respected the Decembrists, and were extremely hospitable in their reception of them.[18]

Upon arrival at places of settlement, exiles had to comply with extensive regulations under a strict governmental regime. Local police watched, regulated, and notated every move that Decembrists attempted to make. Dimitri Zavalishin was thrown into prison for failing to remove his hat before a lieutenant. Not only were political and social activities carefully monitored and prevented, there was also interference regarding religious convictions. Local clergy accused Prince Shakhovskoi of “heresy”, due to his interest in natural sciences. Authorities investigated and restrained other Decembrists for not attending church.[19] The regime thoroughly censored all correspondences, especially communication with relatives. Messages were scrupulously reviewed by both officials in Siberia and the Third Division of the political intelligence service at St. Petersburg. This screening process necessitated dry, careful wording on the part of Decembrists. In the words of Bestuzhev, correspondence bore a “lifeless...imprint of officiality.” [20] Under the settlement regime, allowances were extremely meager. Certain Decembrists, including the Volkonskys, the Murav’yovs, and the Trubetskoys, were rich, but the majority of exiles had no money, and were forced to live off a mere fifteen desyatins (about 16 hectares) of land, the allotment granted to each settler. Decembrists, with little to no knowledge of the land, attempted to eke out a living on wretched soil with next to no equipment. Financial aid from relatives and wealthier comrades saved many; others perished.[21]

Despite extensive restrictions, limitations, and hardships, Decembrists believed that they could improve their situation through personal initiative. A constant stream of petitions came out of Petrovsky Zavod addressed to General Leparskii and Emperor Nicholas I.[22] Most of the petitions were written by Decembrists’ wives who had nobly cast aside social privileges and comfort to follow their husbands into exile.[23] These wives joined under the leadership of Princess Mariia Volkonskaia, and by 1832, through relentless petitions, managed to secure for their men formal cancellation of labor requirements, and several privileges, including the right of husbands to live with their wives in privacy.[22] Decembrists managed to gain transfers and allowances through persuasive petitions as well as through the intervention of family members. This process of petitioning, and the resultant concessions made by the tsar and officials, was and would continue to be a standard practice of political exiles in Siberia. The chain of bureaucratic procedures and orders linking St. Petersburg to Siberian administration was often circumvented or ignored. These breaks in bureaucracy afforded exiles a small capacity for betterment and activism.[24]

Wives of many Decembrists followed their husbands into exile. The expression Decembrist wife is a Russian symbol of the devotion of a wife to her husband. Maria Volkonskaya, the wife of the Decembrist leader Sergei Volkonsky, notably followed her husband to his exile in Irkutsk. Despite the spartan conditions of this banishment, Sergei Volkonsky and his wife, Maria, took opportunities to celebrate the liberalising mode of their exile. Sergei took to wearing an untrimmed beard (rejecting Peter the Great's reforms[25] and salon fashion), wearing peasant dress and socialising with many of his peasant associates with whom he worked the land at his farm in Urik. Maria, equally, established schools, a foundling hospital and a theater for the local population.[26] Sergei returned after thirty years of his exile had elapsed, though his titles and land remained under royal possession. Other exiles preferred to remain in Siberia after their sentences were served, preferring its relative freedom to the stifling intrigues of Moscow and St. Petersburg, and after years of exile there was not much for them to return to. Many Decembrists thrived in exile, in time becoming landowners and farmers. In later years, they would become idols of the populist movement of the 1860s and the 1870s, as the Decembrists' advocacy of reform (including the abolition of serfdom) won them many admirers, the writer Leo Tolstoy among them.

During their time in exile, the Decembrists fundamentally influenced Siberian life. Their presence was most definitely felt culturally and economically, political activity being so far removed from the “pulse of national life” so as to be negligible.[27] While in Petrovsky Zavod, Decembrists taught each other foreign languages, arts and crafts, and musical instruments. They established “academies” made up of libraries, schools, and symposia.[15] In their settlements, Decembrists were fierce advocates of education, and founded many schools for natives, the first of which opened at Nerchinsk. Schools were also founded for women, and soon exceeded capacity. Decembrists contributed greatly to the field of agriculture, introducing previously unknown crops such as vegetables, tobacco, rye, buckwheat, and barley, and advanced agricultural methods such as hothouse cultivation. Trained doctors among the political exiles promoted and organized medical aid. The homes of prominent exiles like Prince Sergei Volkonsky and Prince Sergei Trubetskoi became social centers of their locales. All throughout Siberia, the Decembrists sparked an intellectual awakening: literary writings, propaganda, newspapers, and books from European Russia began to circulate the eastern provinces, the local population developing a capacity for critical political observation.[28] The Decembrists even held a certain influence within Siberian administration; Dimitry Zavalishin played a critical role in developing and advocating Russian Far East policy. Although the Decembrists lived in isolation, their scholarly activities encompassed Siberia at large, including its culture, economy, administration, population, geography, botany, and ecology.[29] Despite restricted circumstances, the Decembrists accomplished an extraordinary amount, and their work was deeply appreciated by Siberians.

On August 26, 1856, with the ascent of Alexander II to the throne, the Decembrists received amnesty, their rights, privileges, and titles restored. Not all chose to return to the West, however. Some were financially inhibited, others had no family to return to, and many were weak with old age. To many, Siberia had become home. Those that did return to European Russia did so with enthusiasm for the enforcement of the Emancipation Reforms of 1861.[30] The exile of the Decembrists led to the permanent implantation of an intelligentsia in Siberia. For the first time, a cultural, intellectual, and political elite came to Siberian society as permanent residents; they integrated with the country and participated alongside natives in its development.[31]

Assessment

With the failure of the Decembrists, Russia's autocracy would continue for almost a century, although serfdom would be officially abolished in 1861. Though defeated, the Decembrists did effect some change on the regime. Their dissatisfaction forced Nicholas to turn his attention inward to address the issues of the empire. In 1826, Speransky was appointed by Nicholas I to head the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery, a committee formed to codify Russian law. Under his leadership, the committee produced a publication of the complete collection of laws of the Russian Empire, containing 35,993 enactments. This codification called the "Full Collection of Laws" (Polnoye Sobraniye Zakonov) was presented to Nicholas I, and formed the basis for the "Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire" (Svod Zakonov Rossiskoy Imperii), the positive law valid for the Russian Empire. Speransky's liberal ideas were subsequently scrutinized and elaborated by Konstantin Kavelin and Boris Chicherin. Although the revolt was a proscribed topic during Nicholas’ reign, Alexander Herzen placed the profiles of executed Decembrists on the cover of his radical periodical Polar Star. Alexander Pushkin addressed poems to his Decembrist friends, Nikolai Nekrasov wrote a long poem about the Decembrist wives, and Leo Tolstoy started writing a novel on that liberal movement, which would later evolve into War and Peace. In the Soviet era Yuri Shaporin produced an opera entitled Dekabristi (The Decembrists), about the revolt, with the libretto written by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy. It premiered at the Bolshoi Theatre on 23 June 1953.[32]

To some extent, the Decembrists were in the tradition of a long line of palace revolutionaries who wanted to place their candidate on the throne, but because the Decembrists also wanted to implement classical liberalism, their revolt has been considered the beginning of a revolutionary movement. The uprising was the first open breach between the government and reformist elements of the Russian nobility, which would subsequently widen.

"Constantine and Constitution" anecdote

There was an anecdote that soldiers in Saint Petersburg were said to chant "Constantine and Constitution", but when questioned, many of them professed to believe that "Constitution" (which is grammatically female in Russian Konstitutsiya) was Constantine's wife.[33]

Pyotr Kakhovsky in a letter to General Levashev, mentioned the anecdote and denied it:

"The story told to Your Excellency that, in the uprising of 14 December the rebels were shouting 'Long live the Constitution!' and that the people were asking 'What is Constitution, the wife of His Highness the Grand Duke?' is not true. It is an amusing invention."[34]

References

- 1 2 Peter Neville (2003) Russia: A Complete History: 120-1

- ↑ Sherman, R and Pearce, R (2002) Pg. 23

- ↑ Mirroring the liberal reaction following the Crimean War in 1854, leading to the emancipation of the serfs in 1861

- ↑ Pestel, quoted in A.G. Mazour 1937, p. 8

- ↑ Edward Crankshaw (1978) The Shadow of the Winter Palace. London, Penguin: 14–16

- ↑ Edward Crankshaw (1978) The Shadow of the Winter Palace. London, Penguin: 15–16

- ↑ Edward Crankshaw (1978) The Shadow of the Winter Palace. London, Penguin: 13–18

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 221

- ↑ Kennan, George (1891). Siberia and the Exile System. London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co. p. 280.

- ↑ G. R. V. Barratt, Voices in Exile (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974), 210

- ↑ Andrew A. Gentes, “Other Decembrists: The Chizov Case and Lutskii Affair As Signifiers of The Decembrists in Siberia,” Slavonica, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2007): 140

- ↑ Andrew A. Gentes, “Other Decembrists: The Chizov Case and Lutskii Affair As Signifiers of The Decembrists in Siberia,” Slavonica, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2007): 135

- 1 2 3 Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 227

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 213

- 1 2 3 Andrew A. Gentes, “Other Decembrists: The Chizov Case and Lutskii Affair As Signifiers of The Decembrists in Siberia,” Slavonica, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2007): 136

- ↑ G. R. V. Barratt, Voices in Exile (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974), 274

- ↑ G. R. V. Barratt, Voices in Exile (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974), 209

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 228

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 231–232

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 233

- ↑ G. R. V. Barratt, Voices in Exile (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974), 303–304

- 1 2 Andrew A. Gentes, “Other Decembrists: The Chizov Case and Lutskii Affair As Signifiers of The Decembrists in Siberia,” Slavonica, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2007): 137

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 243

- ↑ Andrew A. Gentes, “Other Decembrists: The Chizov Case and Lutskii Affair As Signifiers of The Decembrists in Siberia,” Slavonica, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2007): 139

- ↑ When Peter introduced a more systematic form of administration in the Russian Empire through the "table of ranks", he also reformed aristocratic culture. Bureaucrats now served the state, wore European dress and had to conform to certain presentational standards (i.e., they must not wear a beard, which was associated with the old aristocracy, or the Boyar)

- ↑ Figes, O (2002) Pg. 97

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 244

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 243–247

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 252–255

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 259

- ↑ Anatole G. Mazour, The First Russian Revolution, 1825 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1937), 256–260

- ↑ Arthur Jacobs and Stanley Sadie (1996) The Wordsworth Book of Opera: 555

- ↑ Lewinski-Corwin, Edward H. (1917). The political history of Poland. New York: Polish Book Importing Co. p. 415.

- ↑ Lualdi, Katherine J. Sources of The Making of the West, Volume II: Since 1500: Peoples and Cultures. Macmillan. p. 143. ISBN 9780312576127.

Further reading

- Figes, Orlando (2002) Natasha's Dance: a Cultural History of Russia. London. ISBN 0-7139-9517-3

- Mazour, A.G. 1937. The First Russian Revolution, 1825: the Decembrist movement; its origins, development, and significance. Stanford University Press

- Rabow-Edling, Susanna (May 2007). "The Decembrists and the Concept of a Civic Nation". Nationalities Papers. 35 (2): 369–391. doi:10.1080/00905990701254391.

- Sherman, Russell & Pearce, Robert (2002) Russia 1815–81, Hodder & Stoughton

- Eidelman, Natan (1985) Conspiracy against the tsar, Moscow, Progress Publishers, 294 p. (Translation from the Russian by Cynthia Carlile.)

- Crankshaw, E. (1976). The Shadow of the Winter Palace : Russia's Drift to Revolution, 1825–1917. New York: Viking Press.

External links

- Decembrist exile in Irkutsk

- Decembrist exile in Siberia (in Russian)

- Online Museum of the Decembrist movement (in Russian)