Poison

In biology, poisons are substances that cause disturbances in organisms, usually by chemical reaction or other activity on the molecular scale, when an organism absorbs a sufficient quantity.[1][2]

The fields of medicine (particularly veterinary) and zoology often distinguish a poison from a toxin, and from a venom. Poisons are toxins produced by organisms in nature, and venoms are toxins injected by a bite or sting (this is exclusive to animals). The difference between venom and other poisons is the delivery method. Industry, agriculture, and other sectors use poisons for reasons other than their toxicity. Pesticides are one group of substances whose toxicity to various insects and other animals deemed to be pests (e.g., rats and cockroaches) is their prime purpose.

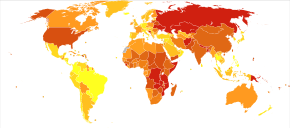

In 2013, 3.3 million cases of unintentional poisonings occurred.[3] This resulted in 98,000 deaths worldwide, down from 120,000 deaths in 1990.[4]

Etymology

The word "poison" was first used in 1200 to mean "a deadly potion or substance"; the English term comes from the "...Old French poison, puison (12c., Modern French poison) "a drink," especially a medical drink, later "a (magic) potion, poisonous drink" (14c.), from Latin potionem (nominative potio) "a drinking, a drink," also "poisonous drink" (Cicero), from potare "to drink".[5] The use of "poison" as an adjective ("poisonous") dates from the 1520s. Using the word "poison" with plant names dates from the 18th century. The term "poison ivy", for example, was first used in 1784 and the term "poison oak" was first used in 1743. The term "poison gas" was first used in 1915.[6]

Terminology

The term "poison" is often used colloquially to describe any harmful substance—particularly corrosive substances, carcinogens, mutagens, teratogens and harmful pollutants, and to exaggerate the dangers of chemicals. Paracelsus (1493–1541), the father of toxicology, once wrote: "Everything is poison, there is poison in everything. Only the dose makes a thing not a poison"[7] (see median lethal dose). The term "poison" is also used in a figurative sense: "His brother's presence poisoned the atmosphere at the party". The law defines "poison" more strictly. Substances not legally required to carry the label "poison" can also cause a medical condition of poisoning.

Some poisons are also toxins, which is any poison produced by animals, vegetables or bacterium, such as the bacterial proteins that cause tetanus and botulism. A distinction between the two terms is not always observed, even among scientists. The derivative forms "toxic" and "poisonous" are synonymous. Animal poisons delivered subcutaneously (e.g., by sting or bite) are also called venom. In normal usage, a poisonous organism is one that is harmful to consume, but a venomous organism uses venom to kill its prey or defend itself while still alive. A single organism can be both poisonous and venomous, but that is rare.[8]

All living things produce substances to protect them from getting eaten, so the term "poison" is usually only used for substances which are poisonous to humans, while substances that mainly are poisonous to a common pathogen to the organism and humans are considered antibiotics. Bacteria are for example a common adversary for Penicillium chrysogenum mold and humans, and since the mold's poison only targets bacteria humans may use it for getting rid of bacteria in their bodies. Human antimicrobial peptides which are toxic to viruses, fungi, bacteria and cancerous cells are considered a part of the immune system.[9]

In nuclear physics, a poison is a substance that obstructs or inhibits a nuclear reaction. For an example, see nuclear poison.

Environmentally hazardous substances are not necessarily poisons, and vice versa. For example, food-industry wastewater—which may contain potato juice or milk—can be hazardous to the ecosystems of streams and rivers by consuming oxygen and causing eutrophication, but is nonhazardous to humans and not classified as a poison.

Biologically speaking, any substance, if given in large enough amounts, is poisonous and can cause death. For instance, several kilograms worth of water would constitute a lethal dose. Many substances used as medications—such as fentanyl—have an LD50 only one order of magnitude greater than the ED50. An alternative classification distinguishes between lethal substances that provide a therapeutic value and those that do not.

Poisoning

Acute poisoning is exposure to a poison on one occasion or during a short period of time. Symptoms develop in close relation to the exposure. Absorption of a poison is necessary for systemic poisoning. In contrast, substances that destroy tissue but do not absorb, such as lye, are classified as corrosives rather than poisons. Furthermore, many common household medications are not labeled with skull and crossbones, although they can cause severe illness or even death. In the medical sense, poisoning can be caused by less dangerous substances than those legally classified as a poison.

Chronic poisoning is long-term repeated or continuous exposure to a poison where symptoms do not occur immediately or after each exposure. The patient gradually becomes ill, or becomes ill after a long latent period. Chronic poisoning most commonly occurs following exposure to poisons that bioaccumulate, or are biomagnified, such as mercury, gadolinium, and lead.

Contact or absorption of poisons can cause rapid death or impairment. Agents that act on the nervous system can paralyze in seconds or less, and include both biologically derived neurotoxins and so-called nerve gases, which may be synthesized for warfare or industry.

Inhaled or ingested cyanide, used as a method of execution in gas chambers, almost instantly starves the body of energy by inhibiting the enzymes in mitochondria that make ATP. Intravenous injection of an unnaturally high concentration of potassium chloride, such as in the execution of prisoners in parts of the United States, quickly stops the heart by eliminating the cell potential necessary for muscle contraction.

Most biocides, including pesticides, are created to act as poisons to target organisms, although acute or less observable chronic poisoning can also occur in non-target organisms (secondary poisoning), including the humans who apply the biocides and other beneficial organisms. For example, the herbicide 2,4-D imitates the action of a plant hormone, which makes its lethal toxicity specific to plants. Indeed, 2,4-D is not a poison, but classified as "harmful" (EU).

Many substances regarded as poisons are toxic only indirectly, by toxication. An example is "wood alcohol" or methanol, which is not poisonous itself, but is chemically converted to toxic formaldehyde and formic acid in the liver. Many drug molecules are made toxic in the liver, and the genetic variability of certain liver enzymes makes the toxicity of many compounds differ between individuals.

Exposure to radioactive substances can produce radiation poisoning, an unrelated phenomenon.

Management

- Initial management for all poisonings includes ensuring adequate cardiopulmonary function and providing treatment for any symptoms such as seizures, shock, and pain.

- Injected poisons (e.g., from the sting of animals) can be treated by binding the affected body part with a pressure bandage and placing the affected body part in hot water (with a temperature of 50 °C). The pressure bandage prevents the poison being pumped throughout the body, and the hot water breaks it down. This treatment, however, only works with poisons composed of protein-molecules.[10]

- In the majority of poisonings the mainstay of management is providing supportive care for the patient, i.e., treating the symptoms rather than the poison.

Decontamination

- Treatment of a recently ingested poison may involve gastric decontamination to decrease absorption. Gastric decontamination can involve activated charcoal, gastric lavage, whole bowel irrigation, or nasogastric aspiration. Routine use of emetics (syrup of Ipecac), cathartics or laxatives are no longer recommended.

- Activated charcoal is the treatment of choice to prevent poison absorption. It is usually administered when the patient is in the emergency room or by a trained emergency healthcare provider such as a Paramedic or EMT. However, charcoal is ineffective against metals such as sodium, potassium, and lithium, and alcohols and glycols; it is also not recommended for ingestion of corrosive chemicals such as acids and alkalis.[11]

- Cathartics were postulated to decrease absorption by increasing the expulsion of the poison from the gastrointestinal tract. There are two types of cathartics used in poisoned patients; saline cathartics (sodium sulfate, magnesium citrate, magnesium sulfate) and saccharide cathartics (sorbitol). They do not appear to improve patient outcome and are no longer recommended.[12]

- Emesis (i.e. induced by ipecac) is no longer recommended in poisoning situations, because vomiting is ineffective at removing poisons.[13]

- Gastric lavage, commonly known as a stomach pump, is the insertion of a tube into the stomach, followed by administration of water or saline down the tube. The liquid is then removed along with the contents of the stomach. Lavage has been used for many years as a common treatment for poisoned patients. However, a recent review of the procedure in poisonings suggests no benefit.[14] It is still sometimes used if it can be performed within 1 hour of ingestion and the exposure is potentially life-threatening.

- Nasogastric aspiration involves the placement of a tube via the nose down into the stomach, the stomach contents are then removed by suction. This procedure is mainly used for liquid ingestions where activated charcoal is ineffective, e.g. ethylene glycol poisoning.

- Whole bowel irrigation cleanses the bowel. This is achieved by giving the patient large amounts of a polyethylene glycol solution. The osmotically balanced polyethylene glycol solution is not absorbed into the body, having the effect of flushing out the entire gastrointestinal tract. Its major uses are to treat ingestion of sustained release drugs, toxins not absorbed by activated charcoal (e.g., lithium, iron), and for removal of ingested drug packets (body packing/smuggling).[15]

Enhanced excretion

- In some situations elimination of the poison can be enhanced using diuresis, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, hyperbaric medicine, peritoneal dialysis, exchange transfusion or chelation. However, this may actually worsen the poisoning in some cases, so it should always be verified based on what substances are involved.

Epidemiology

In 2010, poisoning resulted in about 180,000 deaths down from 200,000 in 1990.[17] There were approximately 727,500 emergency department visits in the United States involving poisonings—3.3% of all injury-related encounters.[18]

Applications

Poisonous compounds may be useful either for their toxicity, or, more often, because of another chemical property, such as specific chemical reactivity. Poisons are widely used in industry and agriculture, as chemical reagents, solvents or complexing reagents, e.g. carbon monoxide, methanol and sodium cyanide, respectively. They are less common in household use, with occasional exceptions such as ammonia and methanol. For instance, phosgene is a highly reactive nucleophile acceptor, which makes it an excellent reagent for polymerizing diols and diamines to produce polycarbonate and polyurethane plastics. For this use, millions of tons are produced annually. However, the same reactivity makes it also highly reactive towards proteins in human tissue and thus highly toxic. In fact, phosgene has been used as a chemical weapon. It can be contrasted with mustard gas, which has only been produced for chemical weapons uses, as it has no particular industrial use.

Biocides need not be poisonous to humans, because they can target metabolic pathways absent in humans, leaving only incidental toxicity. For instance, the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid is a mimic of a plant growth hormone, which causes uncontrollable growth leading to the death of the plant. Humans and animals, lacking this hormone and its receptor, are unaffected by this, and need to ingest relatively large doses before any toxicity appears. Human toxicity is, however, hard to avoid with pesticides targeting mammals, such as rodenticides.

The risk from toxicity is also distinct from toxicity itself. For instance, the preservative thiomersal used in vaccines is toxic, but the quantity administered in a single shot is negligible.

History

Throughout human history, intentional application of poison has been used as a method of murder, pest-control, suicide, and execution.[19][20] As a method of execution, poison has been ingested, as the ancient Athenians did (see Socrates), inhaled, as with carbon monoxide or hydrogen cyanide (see gas chamber), or injected (see lethal injection). Poison's lethal effect can be combined with its allegedly magical powers; an example is the Chinese gu poison. Poison was also employed in gunpowder warfare. For example, the 14th-century Chinese text of the Huolongjing written by Jiao Yu outlined the use of a poisonous gunpowder mixture to fill cast iron grenade bombs.[21]

Figurative use

The term "poison" is also used in a figurative sense. The "[s]lang sense of "alcoholic drink" [is] first attested 1805, American English." (e.g., a bartender might ask a customer "what's your poison?") [22] Figurative use of the term dates from the late 15th century.[23] Figuratively referring to persons as poison dates from 1910.[24] The figurative term "poison-pen letter" became well known in "...1913 by a notorious criminal case in Pennsylvania, U.S.; the phrase dates to 1898."[25]

See also

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)

- Antidote

- Biosecurity

- Contaminated haemophilia blood products

- Food taster

- List of extremely hazardous substances

- List of fictional toxins

- List of poisonings

- List of poisonous plants

- List of types of poison

- Mr. Yuk

- Poison ring

- Saxitoxin

- Toxics use reduction

References

- ↑ "poison" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ "Poison" at Merriam-Webster. Retrieved December 26th, 2014.

- ↑ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborator (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. PMC 4561509

. PMID 26063472. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4.

. PMID 26063472. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. - ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. - ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=poison

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=poison

- ↑ Latin: Dosis sola venenum facit. Paracelsus: Von der Besucht, Dillingen, 1567

- ↑ Hutchinson DA, Mori A, Savitzky AH, Burghardt GM, Wu X, Meinwald J, Schroeder FC (2007). "Dietary sequestration of defensive steroids in nuchal glands of the Asian snake Rhabdophis tigrinus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (7): 2265–70. PMC 1892995

. PMID 17284596. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610785104.

. PMID 17284596. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610785104. - ↑ Reddy KV, Yedery RD, Aranha C (2004). "Antimicrobial peptides: premises and promises". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 24 (6): 536–547. PMID 15555874. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.09.005.

- ↑ Complete diving manual by Jack Jackson

- ↑ Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP, Vale JA (2005). "Position paper: Single-dose activated charcoal". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 43 (2): 61–87. PMID 15822758.

- ↑ Toxicology, American Academy of Clinical (2004). "Position paper: cathartics". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (3): 243–253. PMID 15362590. doi:10.1081/CLT-120039801.

- ↑ American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres Clinical Toxicologists (2004). "Position paper: Ipecac syrup". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (2): 133–143. PMID 15214617. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037421.

- ↑ Vale JA, Kulig K; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologist. (2004). "Position paper: gastric lavage". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (7): 933–943. PMID 15641639. doi:10.1081/CLT-200045006.

- ↑ "Position paper: whole bowel irrigation". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (6): 843–854. 2004. PMID 15533024. doi:10.1081/CLT-200035932.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ↑ Lozano, R (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

- ↑ Villaveces A, Mutter R, Owens PL, Barrett ML. Causes of Injuries Treated in the Emergency Department, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #156. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2013.

- ↑ Kautilya suggests employing means such as seduction, secret use of weapons, poison etc. S.D. Chamola, Kautilya Arthshastra and the Science of Management: Relevance for the Contemporary Society, p. 40. ISBN 81-7871-126-5.

- ↑ Kautilya urged detailed precautions against assassination—tasters for food, elaborate ways to detect poison. "Moderate Machiavelli? Contrasting The Prince with the Arthashastra of Kautilya". Critical Horizons, vol. 3, no. 2 (September 2002). Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1440-9917 (Print) 1568-5160 (Online). doi:10.1163/156851602760586671.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 180.

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=poison

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=poison

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Poison |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poisons. |

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

- American Association of Poison Control Centers

- American College of Medical Toxicology

- Clinical Toxicology Teaching Wiki

- Find Your Local Poison Control Centre Here (Worldwide)

- Poison Prevention and Education Website

- Cochrane Injuries Group, Systematic reviews on the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of traumatic injury (including poisoning)

- Pick Your Poison—12 Toxic Tales by Cathy Newman