Death and state funeral of Josip Broz Tito

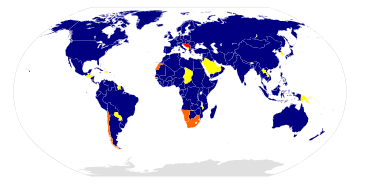

The funeral of Josip Broz Tito, President of Yugoslavia, was held on 8 May 1980, four days after his death on 4 May. His funeral drew many world statesmen, both of non-aligned and aligned countries.[1] Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, it is still regarded as the largest state funeral in history.[2] They included four kings, 31 presidents, six princes, 22 prime ministers and 47 ministers of foreign affairs. They came from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 different countries out of 154 UNO members at the time.[3]

Tito became increasingly ill over the course of 1979. On 7 January and again on 11 January 1980, Tito was admitted to the University Medical Centre in Ljubljana, the capital city of SR Slovenia, with circulation problems in his legs. His left leg was amputated soon afterward due to arterial blockages and he died of gangrene at the Medical Centre Ljubljana on 4 May 1980 at 3:05 in the afternoon, three days short of his 88th birthday. The "Plavi voz" (Blue train, official presidential train) brought his body to the capital Belgrade and he laid in state in the Federal Parliament building until the funeral.

Illness

Tito's health worsened during 1979. He had an arterial embolism in his left leg. In that year he participated in the Havana conference of the Non-Aligned Movement. Tito spent New Year's Eve in his residence in Karađorđevo. As this event was broadcast on state TV, the people of Yugoslavia noticed that he gave and received best wishes while seated. During this time Vila Srna was built for his use near Morović in the event of his recovery.[4]

On January 3, 1980, Tito was admitted to the Ljubljana University Medical Centre for tests on blood vessels in his left leg. Two days later, after the angiography, he was discharged to his residence in Brdo Castle near Kranj, with a recommendation for further intensive treatment. Angiography revealed that Tito's superficial femoral artery and Achilles tendon artery were clogged. The medical council consisted of eight Yugoslav doctors, Michael E. DeBakey from the United States and Marat Knyazev from the Soviet Union.[5]

Following the advice of DeBakey and Knyazev, the medical team attempted an arterial bypass. The first surgery was done in the night between January 12 and 13.[6] At first, it seemed that operation was successful, but after few hours it was clear it was not. Due to severe damage to the arteries, which led to the interruption of blood flow and accelerated tissue devitalization of the left leg, Tito's left leg was amputated on January 20,[7] as otherwise Tito would die of gangrene. When Tito had been told what awaited him, he resisted the operation as long as possible. At the end, after meeting with his two sons Zarko and Miso, he agreed to amputation. After the second surgery, Tito's health temporarily improved, he began rehabilitation, and on 28 January, he was transferred from the Department of cardiovascular surgery to the Department of cardiology. In the first days of February, his health was improving, so Tito could perform some of his regular presidential duties.

When in the beginning of January 1980 it became clear that Tito's life was in grave danger and Yugoslav political leadership begun preparations for his funeral in the utmost secrecy. Tito's wish was that he should be buried in the House of Flowers on Dedinje hill, that overlooks Belgrade. Moma Marković, a director for Radio Television Belgrade, was summoned by Dragoljub Stavrev, a vice president in the federal government, to devise plans for broadcast of the funeral.

Death

Marshal Josip Broz Tito died in the department of cardiovascular surgery at the University Medical Centre in Ljubljana on May 4, 1980 at 3:05 pm, just three days short of his 88th birthday. He died on the seventh floor, in the small most South East corner room which is today used by cardiovascular surgery fellows. The commemorative inscription in the main hall read "The fight for peoples liberation will be a long one, but would have been longer if Tito never lived" (Pot do osvoboditve človeka bo še dolga, a bila bi daljša da ni živel Tito). The inscription was later removed. Immediately upon learning news of the death of Tito, a full extraordinary session of Presidency of Yugoslavia and the Presidency of the Central Committee of League of Communists of Yugoslavia was held in Belgrade starting in 6:00 pm, on which Tito's death was formally declared via a joint statement to all Yugoslavs:

To the working class, all the working people and citizens, and all the nations and nationalities of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia:Comrade Tito has died.

On the day of May 4th, 1980 at 15:05 in Ljubljana, the great heart of the President of our Socialist Yugoslavia, the President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia, the President of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, Marshal of Yugoslavia, and the Commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav armed forces, Josip Broz Tito, has stopped beating.

Great sorrow and pain is shaking up the working class, nations and nationalities of our country, our every citizen, worker, soldier, war veteran, farmer, intellectual, every creator, pioneer and youth, and every girl and mother.

For all his entire life, Tito was a fighter for interests and goals of working class, for the most humane ideals, and desires of our nations and nationalities. Tito is our dearest friend. Seven decades he was burning up in a workers movement. For six decades, he strengthened Yugoslav Communists. For more than four decades, he was the leader of our Party. He was a heroic leader in World War II and in the Socialist revolution. For three and a half decades he led our Socialist country, and he moved our country and our fight for fairer human society into the world history, proving that way to be our most important historic world personality.

During the most fateful times of our survival and development, Tito was bold and worthy of carrying the proletarian flag of our revolution, persistently and consistently linked to the fate of nations and man. He fought all throughout his life and work, lived the revolutionary humanism and fervor with enthusiasm and love for the country.

Tito was not only a visionary, critic and translator of the world. He reviewed the objective conditions and patterns of social movements, into the great ideals and thoughts into action with the million masses of the people that were with him at the helm, and made epochal progressive social transformations.

- —Signed, The Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and the Presidency of Yugoslavia, Belgrade, May 4, 1980.

— [8]

At the same meeting, in accordance with the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution, as amended, it was decided that Lazar Koliševski, Vice President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia, would temporarily take the office of the President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia, and that Cvijetin Mijatović, former member of the Presidency of SR Bosnia and Herzegovina, would take Koliševski's place as state vice president. In accordance with the LCY Statute as amended, former chairman of Presidency of Central Committee of League of Communists of Yugoslavia Stevan Doronjski assumed the post of President of the Presidency of the Central Committee of League of Communists of Yugoslavia. Immediately afterwards the Federal Executive Council (government of Yugoslavia) decided to formally announce a seven-day total national mourning across the country.

Grief

It was a Sunday afternoon, and Yugoslavs were enjoying a weekend. Their usual activities were interrupted when the TV screen went black for 30 seconds. After that, Miodrag Zdravković, newsreader of Radio Television Belgrade, read the following statement live on national television via chroma key:

Comrade Tito has died. That was announced tonight by the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and the Presidency of Yugoslavia to the working class, all the working people and citizens and all the nations and nationalities of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[8]

The same announcement was read out in all republican TV stations.

On Sunday afternoon, Yugoslav Television would usually broadcast soccer games of the national league. That night the derby in Split between NK Hajduk Split and FK Red Star was scheduled to be aired live on national television.[8] During the live broadcast, when the match was in the 41st minute, three men entered the Poljud Stadium pitch, signaling the referee to stop the match. Ante Skataretiko, the president of Hajduk, took the microphone and announced Tito's death to everyone in attendance and to viewers at home, nationwide. What followed were sudden scenes of mass crying with even some players such as Zlatko Vujović collapsing down to the ground and weeping. Players of both teams and referees aligned to stand in a moment of silence. Once the stadium announcer said "May he rest in peace", the entire stadium of 50,000 football fans spontaneously started to sing "Comrade Tito we swear to you, from your path we will never depart".[8][9] The match wasn't resumed, and it had to be replayed much later in the month as decided upon. The scenes from the match shocked the Yugoslav people now mourning his demise.

Dignitaries

The "Plavi voz" (Blue train, official presidential train) brought an empty coffin to the capital Belgrade, due to bad condition of his corpse. Tito's real body was transferred to Belgrade by military helicopter.

Tito's funeral drew many statesmen to Belgrade. Notably absent statesmen from the funeral were Jimmy Carter and Fidel Castro. His death came in the moment when the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan ended American-Soviet détente. Yugoslavia, although a communist state, was non-aligned during the Cold War and fearful that the nation might be invaded like Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan. After learning that Chinese Premier Hua Guofeng would lead the delegation of China, ailing Leonid Brezhnev decided to lead the Soviet delegation. In order to avoid meeting with Leonid Brezhnev whilst in the middle of an electoral campaign for the 1980 United States Presidential election, Carter opted to send his mother Lilian Carter and Vice President Walter Mondale as heads of the US delegation. After realizing that leaders of all Warsaw Pact nations would attend the funeral, Carter's decision was criticized by Presidential candidate George H. W. Bush as a sign that the United States "inferentially slams Yugoslavs at time that country has pulled away from Soviet Union".[10] Carter visited Yugoslavia later in June 1980 and made a visit to Tito's grave.[11][12]

Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor of West Germany was the most active statesman, meeting with Brezhnev, Erich Honecker and Edward Gierek. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher sought to rally world leaders in order to harshly condemn the Soviet invasion. While she was in Belgrade, she held talks with Kenneth Kaunda, Schmidt, Francesco Cossiga and Nicolae Ceaușescu. Brezhnev met with Kim Il-sung and Honecker. James Callaghan, Leader of the British Labour Party explained his presence in Belgrade as an attempt to warm relations between his party and Yugoslav communists, severed more than a decade ago after dissident Milovan Đilas was welcomed by Jennie Lee, Minister for the Arts under Harold Wilson. Mondale avoided the Soviets, ignoring Brezhnev while passing close to him. Soviet and Chinese delegations also avoided each other.

Tito was interred twice on May 8. The first interment was for cameras and dignitaries. The grave was shallow with only a 200 kg replica of the sarcophagus. The second interment was held privately during the night. His coffin was removed, and the shallow grave was deepened. The coffin was enclosed with a copper mask and interred again into a much deeper grave which was sealed with cement and topped with a 9-ton sarcophagus. Communist officials were afraid that someone might steal the corpse, similarly to what happened to Charlie Chaplin. However, the 9 ton sarcophagus had to be put in place with a crane, which would make the funeral unattractive.

State delegations

Source: Mirosavljev, Radoslav (1981). Titova poslednja bitka (Tito's Last Battle) (in Serbo-Croatian). Beograd: Narodna knjiga. pp. 262–264.

Heads of state

State delegations of those countries were headed by their heads of state:

Algeria: Chadli Bendjedid (President), Mohammed Seddik Benyahia (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Algeria: Chadli Bendjedid (President), Mohammed Seddik Benyahia (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Austria: Rudolf Kirchschläger (President), Bruno Kreisky (Federal Chancellor), Willibald Pahr (Foreign Minister)

Austria: Rudolf Kirchschläger (President), Bruno Kreisky (Federal Chancellor), Willibald Pahr (Foreign Minister) Bangladesh: Ziaur Rahman (President), Muhammad Shamsul Haque (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Bangladesh: Ziaur Rahman (President), Muhammad Shamsul Haque (Minister of Foreign Affairs).svg.png) Belgium: King Baudouin I, Wilfried Martens (Prime Minister), Henri Simonet (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Belgium: King Baudouin I, Wilfried Martens (Prime Minister), Henri Simonet (Minister of Foreign Affairs).svg.png) Bulgaria: Todor Zhivkov (Chairman of the State Council)

Bulgaria: Todor Zhivkov (Chairman of the State Council) Canada: Edward Schreyer (Governor General)

Canada: Edward Schreyer (Governor General) Czechoslovakia: Gustáv Husák (President), Miloš Jakeš (First Secretary of the Communist Party), Bohuslav Chňoupek (Ministers of Foreign Affairs)

Czechoslovakia: Gustáv Husák (President), Miloš Jakeš (First Secretary of the Communist Party), Bohuslav Chňoupek (Ministers of Foreign Affairs).svg.png) Ethiopia: Mengistu Haile Mariam (Chairman of the Derg)

Ethiopia: Mengistu Haile Mariam (Chairman of the Derg) Finland: Urho Kekkonen (President), Paavo Väyrynen (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Finland: Urho Kekkonen (President), Paavo Väyrynen (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Greece: Konstantinos Tsatsos (President)

Greece: Konstantinos Tsatsos (President) Guinea: Ahmed Sékou Touré (President), Moussa Diakité (Foreign minister)

Guinea: Ahmed Sékou Touré (President), Moussa Diakité (Foreign minister) Guinea-Bissau: Luís Cabral (President)

Guinea-Bissau: Luís Cabral (President) Hungary: János Kádár (General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party)

Hungary: János Kádár (General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party)%3B_Flag_of_Syria_(1963-1972).svg.png) Iraq: Saddam Hussein (President), Sa'dun Hammadi (Foreign Minister)

Iraq: Saddam Hussein (President), Sa'dun Hammadi (Foreign Minister) Ireland: Patrick Hillery (President), George Colley (Tánaiste)

Ireland: Patrick Hillery (President), George Colley (Tánaiste) Italy: Sandro Pertini (President), Francesco Cossiga (Prime Minister)

Italy: Sandro Pertini (President), Francesco Cossiga (Prime Minister) Jordan: King Hussein, Abdelhamid Sharaf (Prime Minister)

Jordan: King Hussein, Abdelhamid Sharaf (Prime Minister).svg.png) Libya: Muammar al-Gaddafi

Libya: Muammar al-Gaddafi .svg.png) Cyprus: Spyros Kyprianou (President), Nicos A. Rolandis (Foreign Minister)

Cyprus: Spyros Kyprianou (President), Nicos A. Rolandis (Foreign Minister) North Korea: Kim Il-sung (President), Ho Dam (Foreign Minister)

North Korea: Kim Il-sung (President), Ho Dam (Foreign Minister) Democratic Kampuchea: Khieu Samphan (President of the State Presidium) – This delegation represented the UN recognized government of Cambodia (Democratic Kampuchea), although in 1980 Cambodia was de facto ruled as the People's Republic of Kampuchea.[13]

Democratic Kampuchea: Khieu Samphan (President of the State Presidium) – This delegation represented the UN recognized government of Cambodia (Democratic Kampuchea), although in 1980 Cambodia was de facto ruled as the People's Republic of Kampuchea.[13] Luxembourg: Jean (Grand Duke), Gaston Thorn (Deputy Prime Minister)

Luxembourg: Jean (Grand Duke), Gaston Thorn (Deputy Prime Minister) Mali: Moussa Traoré (President), Alain Blondel Bey (Foreign Minister)

Mali: Moussa Traoré (President), Alain Blondel Bey (Foreign Minister) Malta: Anton Buttigieg (President)

Malta: Anton Buttigieg (President) East Germany: Erich Honecker (General Secretary of the Central Committee and the Chairman of the State Council), Oskar Fischer (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

East Germany: Erich Honecker (General Secretary of the Central Committee and the Chairman of the State Council), Oskar Fischer (Minister of Foreign Affairs) West Germany: Karl Carstens (President), Helmut Schmidt (Chancellor), Hans-Dietrich Genscher (Foreign Minister)

West Germany: Karl Carstens (President), Helmut Schmidt (Chancellor), Hans-Dietrich Genscher (Foreign Minister) Norway: King Olav V, Odvar Nordli (Prime Minister)

Norway: King Olav V, Odvar Nordli (Prime Minister) Pakistan: Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (President), Riaz Piracha (Foreign Secretary)

Pakistan: Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (President), Riaz Piracha (Foreign Secretary) Panama: Aristides Royo (President), Carlos Osores (Foreign Minister)

Panama: Aristides Royo (President), Carlos Osores (Foreign Minister) Poland: Edward Gierek (First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party), Wojciech Jaruzelski (Minister of National Defence)

Poland: Edward Gierek (First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party), Wojciech Jaruzelski (Minister of National Defence) Portugal: António Ramalho Eanes (President), Francisco de Sá Carneiro (Prime Minister)

Portugal: António Ramalho Eanes (President), Francisco de Sá Carneiro (Prime Minister).svg.png) Romania: Nicolae Ceaușescu (President), Ilie Verdeț (Prime Minister), Ștefan Andrei (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Romania: Nicolae Ceaușescu (President), Ilie Verdeț (Prime Minister), Ștefan Andrei (Minister of Foreign Affairs) San Marino: Pietro Chiaruzzi and Primo Marani (Captains Regent)

San Marino: Pietro Chiaruzzi and Primo Marani (Captains Regent) Soviet Union: Leonid Brezhnev (General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet), Andrei Gromyko (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Soviet Union: Leonid Brezhnev (General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet), Andrei Gromyko (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) Sweden: King Carl XVI Gustaf, Ola Ullsten (Minister for Foreign Affairs)

Sweden: King Carl XVI Gustaf, Ola Ullsten (Minister for Foreign Affairs) Syria: Hafez al-Assad (President), Abdul Halim Khaddam (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Syria: Hafez al-Assad (President), Abdul Halim Khaddam (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Tanzania: Julius Nyerere (President), Benjamin Mkapa (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Tanzania: Julius Nyerere (President), Benjamin Mkapa (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Togo: Gnassingbé Eyadéma (President)

Togo: Gnassingbé Eyadéma (President)-

.svg.png) Zambia: Kenneth Kaunda (President)

Zambia: Kenneth Kaunda (President)

Heads of government

State delegations of those countries were headed by their heads of government:

.svg.png) Afghanistan: Sultan Ali Keshtmand (First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers), Shah Mohamad Dost (Foreign Minister)

Afghanistan: Sultan Ali Keshtmand (First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers), Shah Mohamad Dost (Foreign Minister).svg.png) Burma: Maung Maung Kha (Prime Minister)

Burma: Maung Maung Kha (Prime Minister)-

.svg.png) Cape Verde: Pedro Pires (Prime Minister)

Cape Verde: Pedro Pires (Prime Minister)  China: Hua Guofeng (Premier), Ji Pengfei (Secretary General of the State Council)

China: Hua Guofeng (Premier), Ji Pengfei (Secretary General of the State Council) France: Raymond Barre (Prime Minister), Jean François-Poncet (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

France: Raymond Barre (Prime Minister), Jean François-Poncet (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Guyana: Ptolemy Reid (Deputy Prime Minister)

Guyana: Ptolemy Reid (Deputy Prime Minister) India: Indira Gandhi (Prime Minister)

India: Indira Gandhi (Prime Minister) Japan: Masayoshi Ōhira (Prime Minister)

Japan: Masayoshi Ōhira (Prime Minister).svg.png) Mongolia: Jambyn Batmönkh (Prime Minister)

Mongolia: Jambyn Batmönkh (Prime Minister) Netherlands: Prince Claus (Prince consort), Prince Bernhard (former Prince consort), Dries van Agt (Prime Minister), Chris van der Klaauw (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Netherlands: Prince Claus (Prince consort), Prince Bernhard (former Prince consort), Dries van Agt (Prime Minister), Chris van der Klaauw (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Peru: Pedro Richter Prada (Prime Minister)

Peru: Pedro Richter Prada (Prime Minister).svg.png) Spain: Adolfo Suárez (Prime Minister), Marcelino Oreja, 1st Marquis of Oreja (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Spain: Adolfo Suárez (Prime Minister), Marcelino Oreja, 1st Marquis of Oreja (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Turkey: Süleyman Demirel (Prime Minister), Hayrettin Erkmen (Foreign Minister)

Turkey: Süleyman Demirel (Prime Minister), Hayrettin Erkmen (Foreign Minister) United Kingdom: Prince Philip (Prince consort), Margaret Thatcher (Prime Minister), Lord Carrington (Foreign Secretary), Fitzroy Maclean (wartime British liaison to Yugoslav partisan troops, personal friend of Tito).

United Kingdom: Prince Philip (Prince consort), Margaret Thatcher (Prime Minister), Lord Carrington (Foreign Secretary), Fitzroy Maclean (wartime British liaison to Yugoslav partisan troops, personal friend of Tito).-

Zimbabwe: Robert Mugabe (Prime Minister)

Zimbabwe: Robert Mugabe (Prime Minister)

Foreign ministers

Delegations of those countries were headed by their deputy heads of state, deputy heads of government or their foreign ministers:

Australia: Andrew Peacock (Minister for Foreign Affairs)

Australia: Andrew Peacock (Minister for Foreign Affairs) Bolivia: Gaston Aroas Levi (Chancellor)

Bolivia: Gaston Aroas Levi (Chancellor).svg.png) Brazil: Oto Agripino Maia (Foreign Minister)

Brazil: Oto Agripino Maia (Foreign Minister) Cameroon: Jean Keucha (Foreign Minister)

Cameroon: Jean Keucha (Foreign Minister) Colombia: Gustavo Balcázar Monzón (Vice President)

Colombia: Gustavo Balcázar Monzón (Vice President) Cuba: Isidoro Malmierca Peoli (Foreign Minister)

Cuba: Isidoro Malmierca Peoli (Foreign Minister) Denmark: Henrik (Prince Consort), Kjeld Olesen (Foreign Minister)

Denmark: Henrik (Prince Consort), Kjeld Olesen (Foreign Minister).svg.png) Egypt: Hosni Mubarak (Vice President)

Egypt: Hosni Mubarak (Vice President) Ghana: Joseph W.S. deGraft-Johnson (Vice-President), Isaac Chinebuah (Minister for Foreign Affairs)

Ghana: Joseph W.S. deGraft-Johnson (Vice-President), Isaac Chinebuah (Minister for Foreign Affairs) Indonesia: Adam Malik (Vice President)

Indonesia: Adam Malik (Vice President) Iran: Sadegh Ghotbzadeh (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Iran: Sadegh Ghotbzadeh (Minister of Foreign Affairs) North Yemen: Qadi Abdel (Vice President)

North Yemen: Qadi Abdel (Vice President) Madagascar: Vice President of the Supreme Revolutionary Council

Madagascar: Vice President of the Supreme Revolutionary Council Mauritius: Harold Edward Water (Foreign Minister)

Mauritius: Harold Edward Water (Foreign Minister) Mexico: Enrique Olivares Santana (Deputy Prime Minister)

Mexico: Enrique Olivares Santana (Deputy Prime Minister) Nigeria: Ishaya Audu (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Nigeria: Ishaya Audu (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Nicaragua: Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann (Foreign Minister)

Nicaragua: Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann (Foreign Minister) New Zealand: Brian Talboys (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs)

New Zealand: Brian Talboys (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs).svg.png) Seychelles: Jacques Hodoul (Minister for Foreign Affairs)

Seychelles: Jacques Hodoul (Minister for Foreign Affairs) Sri Lanka: Abdul Cader Shahul Hameed (Minister of External Affairs)

Sri Lanka: Abdul Cader Shahul Hameed (Minister of External Affairs) Switzerland: Pierre Aubert (Foreign Minister)

Switzerland: Pierre Aubert (Foreign Minister) Thailand: Thanat Khoman (Deputy Prime Minister)

Thailand: Thanat Khoman (Deputy Prime Minister) Uganda: Otema Allimadi (Foreign Minister)

Uganda: Otema Allimadi (Foreign Minister) United States: Walter Mondale (Vice President), Lillian Gordy Carter (mother of President Jimmy Carter)

United States: Walter Mondale (Vice President), Lillian Gordy Carter (mother of President Jimmy Carter).svg.png) Venezuela: José Zambrano Velasco (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Venezuela: José Zambrano Velasco (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Vietnam: Huynh Tan Phat (Deputy Prime Minister)

Vietnam: Huynh Tan Phat (Deputy Prime Minister)

Other state delegations

State delegations of those countries were headed by government ministers, ambassadors or royal house members:

Nepal: Prince Gyanendra of Nepal and K. B. Shahi (Minister of Foreign Affairs)

Nepal: Prince Gyanendra of Nepal and K. B. Shahi (Minister of Foreign Affairs) Andorra

Andorra Angola: Ambrósio Lukoki (Minister of Education and Member of the Politburo of MPLA)

Angola: Ambrósio Lukoki (Minister of Education and Member of the Politburo of MPLA) Argentina: Alberto Varela (Minister of Justice)

Argentina: Alberto Varela (Minister of Justice) Bahamas:

Bahamas: .svg.png) Benin: Tonakpon Capo-Chichi (Minister of Culture) and Agbahe Gregoire (Minister of Tourism and Crafts)

Benin: Tonakpon Capo-Chichi (Minister of Culture) and Agbahe Gregoire (Minister of Tourism and Crafts) Botswana: A. V. Kgarebe (High Commissioner to the United Kingdom)

Botswana: A. V. Kgarebe (High Commissioner to the United Kingdom) Brazil: Jose Ferraz de Rosa (Army General, State Minister, and General Chief of Staff)

Brazil: Jose Ferraz de Rosa (Army General, State Minister, and General Chief of Staff) Burundi: Reni Nkonkengurute (Member of the Politburo and Presidium of the Central Committee of the Union for National Progress, Minister for Presidency affairs)

Burundi: Reni Nkonkengurute (Member of the Politburo and Presidium of the Central Committee of the Union for National Progress, Minister for Presidency affairs) Central African Republic: General Mbale (Minister of Internal Affairs)

Central African Republic: General Mbale (Minister of Internal Affairs) Ecuador: Mario Aleman (Sub-secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Ecuador: Mario Aleman (Sub-secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) Equatorial Guinea: Abaga Julian Esono (Ambassador to France)

Equatorial Guinea: Abaga Julian Esono (Ambassador to France).svg.png) Philippines: Leon ma Guerrero (Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Philippines: Leon ma Guerrero (Ambassador to Yugoslavia) Gabon: Jean Robert Fungu (Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Gabon: Jean Robert Fungu (Ambassador to Yugoslavia) Iceland: Ingvi Sigurður Ingvarsson (Ambassador to Sweden, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Iceland: Ingvi Sigurður Ingvarsson (Ambassador to Sweden, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia) Jamaica: K. G. Hill (Ambassador to Geneva, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Jamaica: K. G. Hill (Ambassador to Geneva, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia) Kenya

Kenya People's Republic of the Congo

People's Republic of the Congo Costa Rica

Costa Rica Kuwait

Kuwait Lebanon

Lebanon Liberia

Liberia.svg.png) Libya

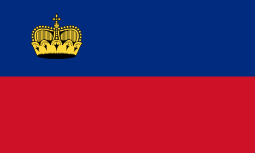

Libya Liechtenstein

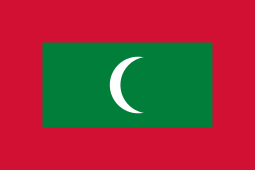

Liechtenstein Maldives

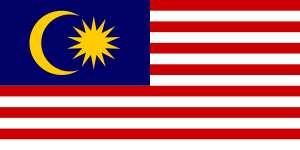

Maldives Malaysia

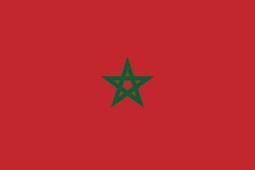

Malaysia Morocco

Morocco Mauritania

Mauritania Monaco

Monaco.svg.png) Mozambique

Mozambique Niger

Niger Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast.svg.png) Oman

Oman.svg.png) Rwanda

Rwanda São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe Senegal

Senegal Sierra Leone: Philip Faboe (Secretary of State)

Sierra Leone: Philip Faboe (Secretary of State) Singapore: David Marshall (Ambassador to France)

Singapore: David Marshall (Ambassador to France) Somalia: Ismail Ali Abokor (President of the People's Assembly, and Member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party)

Somalia: Ismail Ali Abokor (President of the People's Assembly, and Member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party) South Yemen: M. S. Muti (Member of the Politburo and Secretary of the Central Committee of the Yemeni Socialist Party)

South Yemen: M. S. Muti (Member of the Politburo and Secretary of the Central Committee of the Yemeni Socialist Party) Sudan: Sherif Ghasim (Member of the Politburo of the Sudanese Socialist Union)

Sudan: Sherif Ghasim (Member of the Politburo of the Sudanese Socialist Union) Trinidad and Tobago: James O'Neil (Ambassador to Brussels, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Trinidad and Tobago: James O'Neil (Ambassador to Brussels, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia) Tunisia: Sadok Mokaddem (President of the Assembly, and Member of the Politburo of the Socialist Destourian Party) and Habib Bourguiba, Jr.

Tunisia: Sadok Mokaddem (President of the Assembly, and Member of the Politburo of the Socialist Destourian Party) and Habib Bourguiba, Jr. Upper Volta: Tiemoko Marc Garango (Ambassador to West Germany, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia)

Upper Volta: Tiemoko Marc Garango (Ambassador to West Germany, non-resident Ambassador to Yugoslavia)  Uruguay: Walter Ravenna (Minister of National Defense)

Uruguay: Walter Ravenna (Minister of National Defense) Vatican City: Achille Silvestrini (Secretary of the Council for Public Affairs of the Church)

Vatican City: Achille Silvestrini (Secretary of the Council for Public Affairs of the Church) Zaire: Nzondomyo a' Dokpe Lingo (President of the National Assembly)

Zaire: Nzondomyo a' Dokpe Lingo (President of the National Assembly)

Delegations of parties and organizations

International organizations

Arab League: Chedli Klibi (Secretary-General)

Arab League: Chedli Klibi (Secretary-General) European Parliament: Simone Veil (President)

European Parliament: Simone Veil (President) Council of Europe: Franz Karasek (Secretary General)

Council of Europe: Franz Karasek (Secretary General) European Commission: Wilhelm Haferkamp (Vice-President)

European Commission: Wilhelm Haferkamp (Vice-President)- OECD: Emiel van Lennep (Secretary-General)

United Nations: Kurt Waldheim (Secretary-General)

United Nations: Kurt Waldheim (Secretary-General) UNESCO: Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow (Director-General)

UNESCO: Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow (Director-General)

Liberation movements

- Kurdistan National Liberty Army: Abdullah Öcalan (Leader)

- Palestine Liberation Organization: Yasser Arafat (Chairman)

- Polisario Front: Mohamed Abdelaziz (Chairman of the Revolutionary Council)

- Provisional Irish Republican Army: Billy McKee (Leader)

- SWAPO: David Meroro (President of the People's Assembly)

- Umkhonto we Sizwe: Chris Hani (Chief of staff)

Political parties

National Liberation Front: Abdelaziz Bouteflika (president)

National Liberation Front: Abdelaziz Bouteflika (president) Communist Party of Austria: Franz Muhri (president)

Communist Party of Austria: Franz Muhri (president).svg.png) Communist Party of Belgium: Louis Van Geyt (president)

Communist Party of Belgium: Louis Van Geyt (president) Progressive Party of Working People: Ezekias Papaioannou (Secretary General)

Progressive Party of Working People: Ezekias Papaioannou (Secretary General) Communist Party of Denmark: Jørgen Jensen (president)

Communist Party of Denmark: Jørgen Jensen (president) Socialist People's Party: Gert Petersen (president)

Socialist People's Party: Gert Petersen (president) Communist Party of France: Georges Marchais (Secretary general)

Communist Party of France: Georges Marchais (Secretary general) Socialist Party: François Mitterrand (First secretary)

Socialist Party: François Mitterrand (First secretary) Unified Socialist Party: Huguette Bouchardeau (National secretary)

Unified Socialist Party: Huguette Bouchardeau (National secretary) Communist Party of Greece (Interior): Babis Drakopoulos (Secretary General)

Communist Party of Greece (Interior): Babis Drakopoulos (Secretary General) Communist Party of Greece: Charilaos Florakis (Secretary General)

Communist Party of Greece: Charilaos Florakis (Secretary General) PASOK: Andreas Papandreou (Secretary General)

PASOK: Andreas Papandreou (Secretary General) Communist Party of the Netherlands: Henk Hustra (president)

Communist Party of the Netherlands: Henk Hustra (president) Labour Party: Joop den Uyl (Parliamentary group leader)

Labour Party: Joop den Uyl (Parliamentary group leader) Communist Party of Ireland: Andy Barr (president)

Communist Party of Ireland: Andy Barr (president) Sinn Féin: Ruairí Ó Brádaigh (Chairman)

Sinn Féin: Ruairí Ó Brádaigh (Chairman) Communist Party of Italy: Enrico Berlinguer (Secretary General)

Communist Party of Italy: Enrico Berlinguer (Secretary General) Italian Socialist Party: Bettino Craxi (Secretary General)

Italian Socialist Party: Bettino Craxi (Secretary General) Lebanese Communist Party: Nicolas Shawi (Secretary General)

Lebanese Communist Party: Nicolas Shawi (Secretary General) Progressive Socialist Party: Walid Jumblatt (President)

Progressive Socialist Party: Walid Jumblatt (President) Labour Party: Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Deputy leader)

Labour Party: Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Deputy leader) Socialist Union of Popular Forces: Abderahime Buabid (Secretary General)

Socialist Union of Popular Forces: Abderahime Buabid (Secretary General) Party of Progress and Socialism: Ali Yata (Secretary General)

Party of Progress and Socialism: Ali Yata (Secretary General) Communist Party of Mauritius: President

Communist Party of Mauritius: President Social Democratic Party of Germany: Willy Brandt (President and President of the Socialist International)

Social Democratic Party of Germany: Willy Brandt (President and President of the Socialist International) National Party of Nigeria: Augustus Akinloye (President)

National Party of Nigeria: Augustus Akinloye (President) Portuguese Communist Party: Álvaro Cunhal (Secretary General)

Portuguese Communist Party: Álvaro Cunhal (Secretary General) Socialist Party: Mário Soares (Secretary General)

Socialist Party: Mário Soares (Secretary General) Sammarinese Communist Party: Umberto Barulli (Secretary General)

Sammarinese Communist Party: Umberto Barulli (Secretary General).svg.png) African National Congress: Oliver Tambo (President)

African National Congress: Oliver Tambo (President).svg.png) South African Communist Party: Moses Mabhida (Secretary General)

South African Communist Party: Moses Mabhida (Secretary General) Communist Party of Spain: Santiago Carrillo (Secretary General)

Communist Party of Spain: Santiago Carrillo (Secretary General) Spanish Socialist Workers' Party: Felipe González (Secretary General)

Spanish Socialist Workers' Party: Felipe González (Secretary General) Sri Lanka Freedom Party: Sirimavo Bandaranaike (President)

Sri Lanka Freedom Party: Sirimavo Bandaranaike (President) Swiss Party of Labour: Jean Vincent (honorary President)

Swiss Party of Labour: Jean Vincent (honorary President) Swedish Left Party – Communists: Lars Werner (President)

Swedish Left Party – Communists: Lars Werner (President) Republican People's Party: Bülent Ecevit (President)

Republican People's Party: Bülent Ecevit (President) Communist Party of Turkey: İsmail Bilen (General Secretary)

Communist Party of Turkey: İsmail Bilen (General Secretary) Communist Party of Britain: Gordon McLanan (Secretary General)

Communist Party of Britain: Gordon McLanan (Secretary General) Labour Party: James Callaghan (Leader)

Labour Party: James Callaghan (Leader)

References

- ↑ Jimmy Carter (4 May 1980). "Josip Broz Tito Statement on the Death of the President of Yugoslavia". Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ Vidmar, Josip; Rajko Bobot; Miodrag Vartabedijan; Branibor Debeljaković; Živojin Janković; Ksenija Dolinar (1981). Josip Broz Tito – Ilustrirani življenjepis. Jugoslovenska revija. p. 166.

- ↑ Ridley, Jasper (1996). Tito: A Biography. Constable. p. 19. ISBN 0-09-475610-4.

- ↑ "Raj u koji Broz nije stigao". Blic. 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "Specialist consults on Tito". Lodi News. January 7, 1980.

- ↑ "Tito surgery succesuful". Beaver County Times. January 14, 1980.

- ↑ "8 DOCTORS SAY TITO IS IN GOOD CONDITION; First Official Response to Surgery Strengthens Hope He Will Return to Duties 'Within Limits of Normal' Control Would Likely Continue Concentration on Foreign Affairs". New York Times. January 22, 1980.

- 1 2 3 4 "Anniversary of Marshal Tito's death". http://yugoslavian.blogspot.com/. 4 May 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Borneman, John. Death of the Father: An Anthropology of the End in Political Authority. Berghahn Books.

- ↑ "Bush Blasts Carter For Not Attending Tito Funeral". Lakeland Ledger. May 9, 1980.

- ↑ "Jimmy Carter Visits President Tito's Grave, 1980". Yugoslavia – Virtual Museum. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Jimmy Carter: "Yugoslavia: Conclusion of State Visit Joint Statement. ", June 29, 1980. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=44655.

- ↑ Martin, Marie Alexandrine (1994). Cambodia: A Shattered Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 0520070526.